Floyd at peak intensity on September 13, north of Hispaniola | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 7, 1999 |

| Extratropical | September 17, 1999 |

| Dissipated | September 19, 1999 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 921 mbar (hPa); 27.20 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 85 |

| Damage | $6.5 billion (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lucayan Archipelago, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| Effects

Other wikis | |

Hurricane Floyd was a very powerful Cape Verde hurricane which struck the Bahamas and the East Coast of the United States. It was the sixth named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane in the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season. Floyd triggered the fourth largest evacuation in US history (behind Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Gustav, and Hurricane Rita) when 2.6 million coastal residents of five states were ordered from their homes as it approached. The hurricane formed off the coast of Africa and lasted from September 7 to 19, becoming extratropical after September 17, and peaked in strength as a very strong Category 4 hurricane. It was among the largest Atlantic hurricanes of its strength ever recorded, in terms of gale-force diameter.[1]

Floyd was once forecast to strike Florida, but turned away. Instead, Floyd struck the Bahamas at peak strength, causing heavy damage. It then moved parallel to the East Coast of the United States, causing massive evacuations and costly preparations from Florida through the Mid-Atlantic states. The storm weakened significantly, however, before striking the Cape Fear region, North Carolina as a very strong Category 2 hurricane, and caused further damage as it traveled up the Mid-Atlantic region and into New England.

The hurricane produced torrential rainfall in Eastern North Carolina, adding more rain to an area already hit by Hurricane Dennis just weeks earlier. The rains caused widespread flooding over a period of several weeks; nearly every river basin in the eastern part of the state exceeded 500-year flood levels. In total, Floyd was responsible for 85 fatalities and $6.5 billion (1999 USD) in damage. Due to the destruction, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Floyd and replaced it with Franklin.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Floyd originated from a tropical wave that exited the west coast of Africa on September 2. The wave moved generally westward, presenting a general curvature in its convection, or thunderstorms, but little organization at first. By September 5, a center of circulation was evident within the convective system. Over the next day, the thunderstorms increased in intensity as they organized into a curved band. Aided by favorable outflow, the system organized further into Tropical Depression Eight late on September 7, located about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. With a strong ridge of high pressure to its north, the nascent tropical depression moved to the west-northwest, where environmental conditions favored continued strengthening,[2] including progressively warmer water temperatures.[3] On issuing its first advisory, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) anticipated that the depression would intensify into a hurricane within three days,[4] a forecast that proved accurate.[2] On its second advisory, NHC forecaster Lixion Avila stated that the depression had "all the ingredients...that we know of...to become a major hurricane eventually."[3]

Early on September 8, the depression became sufficiently well-organized for the NHC to upgrade it to Tropical Storm Floyd.[2] The storm had a large circulation,[5] but Floyd initially lacked a well-defined inner core, which resulted in only slow strengthening.[2] The first Hurricane Hunters mission occurred on September 9, which observed the developing storm.[6] On September 10, Floyd intensified into a hurricane about 230 mi (370 km) east-northeast of the Lesser Antilles. Around that time, the track shifted more to the northwest, steered by a tropical upper tropospheric trough north of Puerto Rico.[2] An eye developed in the center of the hurricane, signaling strengthening.[7] On September 11, Hurricane Floyd moved through the upper-level trough, which, in conjunction with an anticyclone over the eastern Caribbean, disrupted the outflow and caused the winds to weaken briefly. The hurricane re-intensified on September 12 as its track shifted more to the west, steered by a ridge to the north. That day, the NHC upgraded Floyd to a major hurricane, or a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[2]

Over a 24-hour period from September 12–13, Hurricane Floyd rapidly intensified, aided by warm waters east of The Bahamas. During that time, the maximum sustained winds increased from 110 to 155 mph (177 to 249 km/h),[nb 1] making Floyd a strong Category 4 hurricane. This was based a 90% reduction of an observation by the Hurricane Hunters, which recorded flight-level winds of 171 mph (276 km/h). Around the same time, the pressure dropped to 921 mb (921 hPa; 27.2 inHg),[2] which was the fourth-lowest pressure for a hurricane not to reach Category 5 intensity in the Atlantic Ocean – only Hurricanes Iota, Gloria and Opal had lower pressures than Floyd.[8] Around this time, tropical cyclone forecast models suggested an eventual landfall in the Southeastern United States from Palm Beach, Florida to South Carolina.[9]

At its peak, tropical storm-force winds spanned a diameter of 580 mi (930 km), making Floyd one of the largest Atlantic hurricanes of its intensity ever recorded.[1] For about 12 hours, Hurricane Floyd remained just below Category 5 status while crossing The Bahamas. Late on September 13, the eye of the hurricane passed just north of San Salvador and Cat Islands. On the next day, the hurricane made landfalls on Eleuthera and Abaco islands.[2] During this time, Floyd underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, in which an outer eyewall developed, causing the original eye to dissipate near Eleuthera. This caused a temporary drop in sustained winds to Category 3 status, only for Floyd to restrengthen briefly to a Category 4 on September 15.[2]

While approaching the southeastern United States, a strong mid- to upper-level trough eroded the western portion of the high-pressure ridge, which had been steering Floyd for several days. The break in the ridge caused Floyd to turn to the northwest. After the hurricane completed its eyewall replacement cycle, Floyd had a large 57 mi (93 km) eye. The large storm gradually weakened after exiting The Bahamas, due to drier air and increasing wind shear. On September 15, Floyd paralleled the east coast of Florida about 110 mi (170 km) offshore, as it accelerated to the north and north-northeast. At around 06:30 UTC on September 16, Hurricane Floyd made landfall in Cape Fear, North Carolina with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h), a Category 2. The eyewall had largely dissipated by that time. Continuing northeastward along a cold front, Floyd moved through eastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia, weakening to tropical storm status by late on September 16. The storm gradually lost its tropical characteristics as it quickly moved through the Delmarva Peninsula, eastern New Jersey, Long Island, and New England. Late on September 17, Floyd transitioned into an extratropical cyclone near the coast of southern Maine. The storm continued to the northeast, passing through New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland on September 18. On the following day, a larger extratropical storm over the North Atlantic Ocean absorbed what was once Hurricane Floyd.[2]

Preparations

Early in Floyd's duration, the hurricane posed a threat to the Lesser Antilles, prompting tropical storm watches for Antigua and Barbuda, Anguilla, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthelemy. After the storm bypassed the region, the government of The Bahamas issued a tropical storm warning and a hurricane watch for the Turks and Caicos Islands and the southeast Bahamas, as well as hurricane warnings for the central and northwestern Bahamas.[2]

Although Floyd's track prediction was above average while out at sea, the forecasts as it approached the coastline were merely average compared to forecasts from the previous ten years. The official forecasts did not predict Floyd's northward track nor its significant weakening before landfall.[10] At some point, the NHC issued a hurricane warning for nearly all of the East Coast of the United States, from Florida City, Florida, to Plymouth, Massachusetts; however, only a fraction of this area actually received hurricane-force winds. The last time such widespread hurricane warnings occurred was during Hurricane Donna in 1960.[2]

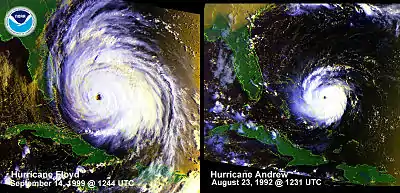

Initial fears were of a direct hit as a large Category 4 hurricane in Florida, potentially costlier and deadlier than Hurricane Andrew had been in 1992. In preparation for a potentially catastrophic landfall, more than one million Florida residents were told to evacuate, of which 272,000 were in Miami-Dade County.[11] U.S. President Bill Clinton declared a federal state of emergency in both Florida and Georgia in anticipation of the storm's approach.[12] As the storm turned to the north, more people were evacuated as a progressively larger area was threatened. The massive storm prompted what was then the largest peacetime evacuation in U.S. history, with around 2.6 million evacuating coastal areas in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas.[13]

With the storm predicted to hit near Cape Canaveral with winds of over 140 mph (230 km/h), all but 80 of Kennedy Space Center's 12,500-person workforce were evacuated. The hangars that house three space shuttles can withstand winds of only 105 mph (169 km/h), and a direct hit could have resulted in potentially billions of dollars in damage of space equipment.[14] In the theoretical scenario, the damage would be caused by water, always a potential problem in an area only nine feet above sea level. If water entered the facility, it would damage the electronics as well as requiring a complete inspection of all hardware.[15] When Floyd actually passed by the area, Kennedy Space Center only reported light winds with minor water intrusion. Damage was minor overall, and was repaired easily.[16]

A hurricane warning was issued for the North Carolina coastline 27 hours prior to landfall. However, due to the size of the storm, initial forecasts predicted nearly all of the state would be affected in one form or another. School systems and businesses as far west as Asheville shut down for the day landfall was predicted. As it turned out, only the Coastal Plain sustained significant damage; much of the state west of Raleigh escaped unscathed. In New York City, public schools were closed on September 16, 1999, the day Floyd hit the area. This was a rare decision by the city, as New York City public schools close on average once every few years. Before Floyd, the last time New York City closed its schools was for the Blizzard of 1996. After Floyd, the next time its public schools would close was due to a blizzard on March 5, 2001.[17] Walt Disney World also closed for the first time in its history due to the storm. The resort would later close during hurricanes Frances and Jeanne in 2004, Matthew in 2016, Irma in 2017, Dorian in 2019, and Ian in 2022.[18][19]

A state of emergency was declared in Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey prompting schools statewide to be shut down on September 16. In Delaware, about 300 people evacuated.[20][21][22]

In Atlantic Canada, the Canadian Hurricane Centre issued 14 warnings related to Floyd, generating significant media interest. About 100 Sable Offshore Energy Project employees were evacuated to the mainland. In southwestern Nova Scotia, 66 schools were closed, and provincial ferry service with Bar Harbor, Maine was canceled.[23]

Impact

| State/country | Deaths |

|---|---|

| The Bahamas | 1 |

| North Carolina | 51 |

| Virginia | 4 |

| Maryland | 2 |

| Delaware | 2 |

| Pennsylvania | 13 |

| New Jersey | 8 |

| New York | 2 |

| Connecticut | 1 |

| Vermont | 1 |

| Total | 85 |

With a death toll of 85, Hurricane Floyd was the deadliest United States hurricane since Hurricane Agnes in 1972. The storm was the third-costliest hurricane in the nation's history at the time, with monetary damage estimated at $6.5 billion (1999 USD); it ranked the 19th costliest as of 2017.[24] Most of the deaths and damage were from inland, freshwater flooding in eastern North Carolina.

Caribbean and Bahamas

Around when Floyd first became a hurricane, its outer bands moved over the Lesser Antilles.[25]

Hurricane Floyd lashed the Bahamas with winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) and waves up to 50 ft (15 m) in height.[13] A 20 ft (6.10 m) storm surge inundated many islands with over five ft (1.5 m) of water throughout.[26] The wind and waves toppled power and communication lines, severely disrupting electricity and telephone services for days. Damage was greatest at Abaco Island, Cat Island, San Salvador Island, and Eleuthera Island, where Floyd uprooted trees and destroyed a significant number of houses.[27] Numerous restaurants, hotels, shops, and homes were devastated, severely limiting in the recovery period tourism on which many rely for economic well-being.[28] Damaged water systems left tens of thousands across the archipelago without water, electricity, or food. Despite the damage, however, few deaths were reported, as only one person drowned in Freeport, and there were few injuries reported.[26]

Southeastern United States

For several days, Hurricane Floyd paralleled the east coast of Florida, spurring widespread evacuations. Ultimately, the storm left $50 million in damage, mostly in Volusia county. There, high winds and falling trees damaged 337 homes. The highest recorded wind gust in the state was 69 mph (111 km/h) in Daytona Beach. Beach erosion affected much of the state's Atlantic coast. The most significant effects were in Brevard and Volusia counties, where waves damaged houses and piers. Rainfall in the state reached 3.2 in (81 mm) in Sanford.[2][29][30]

Farther north in Georgia, Floyd produced wind gusts of 53 mph (85 km/h) at Savannah International Airport. The winds knocked down a few trees and power lines near the coast, but statewide damage was minimal. In Savannah, the hurricane produced tides 3.3 ft (1.0 m) above normal. Rainfall was light in the state, reaching 0.85 in (22 mm) in Newington.[31][2]

Tropical storm force winds affected the entirety of the South Carolina coastline, with statewide damage estimated at $17 million. Sustained winds reached 54 mph (87 km/h) at the Charleston National Weather Service Office, which also recorded wind gusts of 85 mph (137 km/h). The winds destroyed a few roofs and knocked down thousands of trees, leaving more than 200,000 people without electricity. The hurricane produced above normal tides along the coast, reaching 10.1 ft (3.1 m) above normal in Charleston Harbor. The waves caused minor to moderate beach erosion. At Myrtle Beach International Airport, Hurricane Floyd dropped 16.06 in (408 mm) of rainfall, the highest recorded in the state.[32][2]

North Carolina

North Carolina received the brunt of the storm's destruction. In all, Hurricane Floyd caused 51 fatalities in North Carolina, much of them from freshwater flooding, as well as billions in damage.

The storm surge from the large hurricane amounted to 9–10 ft (2.7–3.0 m) along the southeastern portion of the state. The hurricane also spawned numerous tornadoes, most of which caused only minor damage. Damage to power lines left over 500,000 customers without electricity at some point during the storm's passage.[2]

Just weeks prior to Floyd hitting, Hurricane Dennis brought up to 15 in (380 mm) of rain to southeastern North Carolina. When Hurricane Floyd moved across the state in early September, it produced torrential rainfall, amounting to a maximum of 19.06 in (484 mm) in Wilmington. Though it moved quickly, the extreme rainfall was due to Floyd's interaction with an approaching cold front across the area.[2]

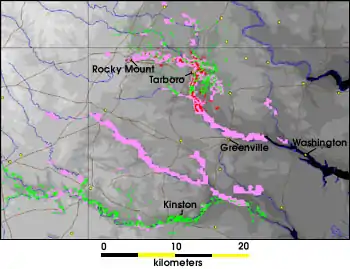

Extensive flooding, especially along NC Hwy 91 and the White Oak Loop neighborhood, led to overflowing rivers; nearly every river basin in eastern North Carolina reached 500 year or greater flood levels.[33] Most localized flooding happened overnight; Floyd dropped nearly 17 in (430 mm) of rain during the hours of its passage and many residents were not aware of the flooding until the water came into their homes. The U. S. Navy, National Guard and the Coast Guard performed nearly 1700 fresh water rescues of people trapped on the roofs of their homes due to the rapid rise of the water. By contrast, many of the worst affected areas did not reach peak flood levels for several weeks after the storm, as the water accumulated in rivers and moved downstream (see flood graphic at right).

The passage of Hurricane Irene four weeks later contributed an additional six in (150 mm) of rain over the still-saturated area, causing further flooding.

The Tar River suffered the worst flooding, exceeding 500-year flood levels along its lower stretches; it crested 24 ft (7.3 m) above flood stage. Flooding began in Rocky Mount, as much as 30% of which was underwater for several days. In Tarboro, much of the downtown was under several feet of water.[34] Nearby, the town of Princeville was largely destroyed when the waters of the Tar poured over the town's levee, covering the town with over 20 ft (6.1 m) of floodwater for ten days.[35] Further downstream, Greenville suffered very heavy flooding; damages in Pitt County alone were estimated at $1.6 billion (1999 USD, $2.81 billion 2022 USD).[13] Washington, where the peak flood level was observed, was likewise devastated. Some residents in Greenville had to swim six feet underwater to reach the front doors of their homes and apartments.[36] Due to the heavy flooding in downtown Greenville, the East Carolina Pirates were forced to relocate their football game against #9 Miami to N.C. State's Carter–Finley Stadium in Raleigh, where they beat the Hurricanes 27–23.[37]

The Neuse River, Roanoke River, Waccamaw River, and New River exceeded 500-year flood levels, although damage was lower in these areas (compared to the Tar River) because of lower population densities. Because most of the Cape Fear River basin was west of the peak rainfall areas, the city of Wilmington was spared the worst flooding despite having the highest localized rainfall; however, the Northeast Cape Fear River (a tributary) did exceed 500-year flood levels. Of the state's eastern rivers, only the Lumber River escaped catastrophic flooding.[33]

Rainfall and strong winds affected many homes across the state, destroying 7,000, leaving 17,000 uninhabitable, and damaging 56,000. Ten thousand people resided in temporary shelters following the storm. The extensive flooding resulted in significant crop damage. As quoted by North Carolina Secretary of Health and Human Services H. David Bruton, "Nothing since the Civil War has been as destructive to families here. The recovery process will be much longer than the water-going-down process."[13] Around 31,000 jobs were lost from over 60,000 businesses through the storm, causing nearly $4 billion (1999 USD, $7.02 billion 2022 USD) in lost business revenue.[38] In much of the affected area, officials urged people to either boil water or buy bottled water during Floyd's aftermath.[39]

In contrast to the problems eastern North Carolina experienced, much of the western portion of the state remained under a severe drought.[13]

Virginia

Hurricane Floyd left $101 million in damage in Virginia, and contributed to four fatalities – two from fallen trees in Fairfax and Halifax County, one in a traffic accident in Hanover County, and a man in Accomack County who drowned in his submerged vehicle.[40] As in North Carolina and elsewhere along its path, Floyd dropped torrential rainfall across eastern Virginia, reaching 16.57 in (421 mm) in Newport News.[2] While Floyd moved through southeastern Virginia, it was still at hurricane status, producing winds strong enough to knock down hundreds of trees and power lines. The highest sustained winds in the state were 46 mph (74 km/h) at Langley Air Force Base.[2] Wind gusts were much stronger, reaching 100 mph (160 km/h) on the James River Bridge.[41] Floyd's winds and rains knocked down hundreds of trees across the state, some centuries old.[40]

The heavy rains washed out several roads, and closed regional routes including Interstate 95 between Emporia and Petersburg, U.S. Route 58 between Emporia and Franklin, and U.S. Route 460 near Wakefield.[41] The rainfall led to overflowing rivers in the Chowan River Basin, some of which exceeded 500-year flood levels.[33] The Blackwater River reached 100-year flood levels and flooded Franklin with 12 ft (3.7 m) of water. Extensive road damage occurred there, isolating the area from the rest of the state. Some 182 businesses and 150 houses were underwater in Franklin from the worst flooding in 60 years. In addition, two dams along the Rappahannock River burst from the extreme flooding. Throughout all of Virginia, Floyd damaged 9,250 houses.[40] In addition to the heavy rainfall, tides in Norfolk were 3.9 ft (1.2 m) above normal, resulting moderate to locally severe coastal flooding. Along the Chesapeake Bay, Floyd produced a 5 to 7 ft (1.5 to 2.1 m) storm surge, causing up to 6 ft (1.8 m) of flooding in Accomack County homes.[41] Floyd's winds and rains knocked down hundreds of trees across the state, some centuries' old.[40]

Mid-Atlantic

As Floyd moved northward from Virginia, a stalled cold front acted as a conveyor belt of tropical moisture across the Mid-Atlantic.[2] Wind gusts in Washington, D.C. reached 56 mph (90 km/h) at the Children's National Medical Center. The storm knocked down trees and dropped heavy rainfall, causing a shop on New York Avenue NW to close after the roof collapsed.[40]

The hurricane's rainbands moved across Maryland, dropping 12.59 in (320 mm) of rainfall in Chestertown, Maryland.[42] Statewide, about 450 people required evacuated from low-lying areas. A mudslide in Anne Arundel County stranded five trains carrying about 1,000 passengers. Flooding closed 225 roads statewide, with dozens of motorists requiring rescue, and more than 90 bridges were damaged. A man in Centreville died while attempting to jump a washed out bridge on his motorcycle. High tides, 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m) above normal, affected coastal areas of St. Mary's, Calvert, Harford, and Anne Arundel counties, with 5 houses destroyed and 23 severely damaged. Flooding inundated the only bridge to St. George Island, stranding six people. The highest statewide wind gust – 71 mph (114 km/h) – occurred in Tall Timbers, while the highest wind gust in eastern Maryland was 52 mph (83 km/h) in Ocean City.[43][20] The winds knocked down hundreds of trees, including the nearly 400 year–old Liberty Tree at St. John's College in Annapolis.[43][44] The winds also knocked down power lines, leaving about 500,000 customers without electricity. Two people were injured, and one person killed, from Carbon monoxide poisoning related to using a generator. The Anne Arundel county fair was canceled for the first time in its history.[43] In Baltimore, the Baltimore Orioles postponed a baseball game.[45] Statewide damage was estimated at $7.9 million.[46]

In Delaware, Hurricane Floyd left $8.42 million in damage.[21] The storm dropped torrential rainfall, reaching 12.58 in (320 mm) in Greenwood, Delaware.[42] During the storm, Greenwood recorded 10.58 in (269 mm), breaking the record for the state's highest 24 hour rainfall total. The rains caused record crests along rivers and streams in New Castle County. The White Clay Creek crested at 17.6 ft (5.4 m), and was above flood stage for 18 hours. Statewide, Floyd damaged 171 homes, and caused 33 homes to be condemned. Flooding closed hundreds of roads and bridges, with two bridges and a few miles of track belonging to the Wilmington and Western Railroad washed out. Dozens of motorists required rescue. Winds in the state reached 64 mph (104 km/h) at Cape Henlopen along the coast. The winds knocked down hundreds of trees and power lines, leaving about 25,000 people without power.[2][21]

As Floyd continued up the coast, it dropped heavy rainfall in New Jersey, reaching 14.13 in (359 mm) in Little Falls; this was the highest statewide rain from a tropical cyclone since 1950.[47] Following the state's fourth-worst drought in a century,[48] the rains collected in rivers and streams, causing record flooding at 18 river gauges, and mostly affecting the Raritan, Passaic, and Delaware basins.[49][22] Statewide damage totaled $250 million (1999 USD), much of it in Somerset and Bergen counties. This made Floyd the costliest natural disaster in New Jersey's history, until it was surpassed by Hurricane Irene in 2011.[50] Seven people died in New Jersey during Floyd's passage – six due to drowning, and one in a traffic accident. A police lieutenant took his life after working for nearly 48 hours coordinating floodwater rescues. In Bound Brook, the Raritan crested at a record 42.5 ft (13.0 m) on September 16, well above the 28 ft (8.5 m) flood stage, and exceeding the previous record of 37.5 ft (11.4 m) set during Tropical Storm Doria in 1971. Downtown Bound Brook was flooded 13 ft (4.0 m), causing 200 buildings to be condemned. In Manville, the Raritan crested at a record 27.5 ft (8.4 m), nearly double the flood stage of 14 ft (4.3 m). Parts of Manville were flooded to a depth of 10 ft (3.0 m), which damaged 1,500 homes, caused 284 homes to be condemned, and forced 1,000 people to evacuate. A water treatment plant was damaged in Bridgewater Township, forcing nearly 500,000 people in Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, and Somerset counties to boil water for eight days.[22][49] The Rochelle Park, New Jersey hub of Electronic Data Systems was inundated by the nearby Saddle River, disrupting service to as many as 8,000 ATMs across the United States.[51] Flooding in an adjoining Bell Atlantic switching facility cut off phone service to one million customers in the area.[52]

In Pennsylvania, Floyd killed 13 people, largely due to drownings, fallen trees, or heart attacks, and another 40 people were severely injured. The hurricane left about $60 million in damage, mostly related to its heavy rainfall, which peaked at 12.13 in (308 mm) in Marcus Hook.[42] The highest wind gust was 58 mph (93 km/h) occurred at the Commodore Barry Bridge. The two hardest-hit counties were Delaware and Bucks, where more than 10,000 homes were flooded, including 200 that were damaged to the point of being uninhabitable. More than 4,000 people statewide lost their homes due to the storm. Many creeks swelled to record levels, in some cases over double their estimated flood stage, which left motorists in need of rescue, including a bus with 11 students in Buckingham Township. Statewide, Floyd left over 500,000 homes and businesses without power.[53]

As Floyd moved through New York, its precipitation reached 12.21 in (310 mm) in Cairo. Floyd's rainfall resulted in flooding that killed two people in the state, and caused several creeks and rivers to exceed their banks. In the Albany area, Normans Kill rose to extremely high levels, and the resultant flood waters damaged nearby buildings. The floods washed out portions of several roads, and destroyed a dam on a mill pond near Lake Placid. The Saw Mill and Bronx rivers both overflowed, causing urban flooding. The heavy rainfall triggered mudslides on the bluffs overlooking the Hudson River near the Tappan Zee Bridge. Winds in the state reached 54 mph (87 km/h) at Stewart International Airport. The winds, combined with saturated ground from the rainfall, knocked down hundreds of trees and power lines, leaving over 100,000 people without power. Damage was estimated at $14.6 million.[13][54][2]

New England and Canada

Floyd's heavy rainfall continued into New England, with 11.13 in (283 mm) of rain reported at the Danbury Airport in Connecticut. One person drowned in the state due to the swollen Quinnipiac River.[55] Floyd's effects in Rhode Island were limited to rainfall and winds, which brought down trees and power lines.[56] Wind gusts in Massachusetts reached 76 mph (122 km/h) at the New Bedford Hurricane Barrier, strong enough to knock down power lines.[57] In New Hampshire, Floyd's winds caused power outages for about 10,000 people, while heavy rains rose the banks of rivers.[58] In Randolph, Vermont, a tree fell onto a mobile home, killing its occupant.[59] About 15,000 residents were affected by power outages in Maine.[60]

The remnants of Floyd produced rainfall and gusty winds from Ontario to Atlantic Canada, with 118 km/h (73 mph) occurring along the Saint Lawrence River in Quebec, the strongest winds in the country.[23] The high winds damaged corn and other crops along the river's south shore from the l'Amiante to Bellechasse regions.[61] The highest rainfall in Canada also occurred in eastern Quebec, reaching 4.8 in (122 mm). Power outages affected Montreal and Quebec City, causing classes to be canceled at the Université de Montréal. Inclement weather was a potential factor in a five car accident on Autoroute 15 in Quebec City. Minor traffic accidents also occurred in the Maritimes. Heavy rainfall backed up storm drains in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The Confederation Bridge connecting Prince Edward Island to the mainland shut down during the storm due to 72 miles per hour (116 km/h) winds. About 6,000 people lost power in Nova Scotia.[23]

Aftermath

To help the affected citizens, the Bahamas Red Cross Society opened 41 shelters, though within one week many returned home.[62] The Bahamas required $435,000 (1999 USD; $764,161 2024 USD) in aid following the storm, much of it in food parcels.[26] The Inter-American Development Bank loaned $21 million (1999 USD; $36.9 million 2024 USD) to the archipelago to restore bridges, roads, seawalls, docks, and other building projects in the aftermath of the hurricane.[63]

Due to its high impact, extensive damage, and loss of life, the name Floyd was retired by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2000, and it will never again be used for another future Atlantic hurricane. It was replaced with Franklin in the 2005 season.

Criticism of FEMA

The Hurricane Floyd disaster was followed by what many judged to be a very slow federal response. Fully three weeks after the storm hit, Jesse Jackson complained to FEMA Director James Lee Witt on his CNN program Both Sides Now, "It seemed there was preparation for Hurricane Floyd, but then came Flood Floyd. Bridges are overwhelmed, levees are overwhelmed, whole towns under water ... [it's] an awesome scene of tragedy. So there's a great misery index in North Carolina." Witt responded, "We're starting to move the camper trailers in. It's been so wet it's been difficult to get things in there, but now it's going to be moving very quickly. And I think you're going to see a—I think the people there will see a big difference [within] this next weekend."

Ecological effects

Runoff from the hurricane created significant problems for the ecology of North Carolina's rivers and sounds. In the immediate aftermath of the storm, freshwater runoff, sediment, and decomposing organic matter caused salinity and oxygen levels in Pamlico Sound and its tributary rivers to drop to nearly zero. This raised fears of massive fish and shrimp kills, as had happened after Hurricane Fran and Hurricane Bonnie, and the state government responded quickly to provide financial aid to fishing and shrimping industries. Strangely, however, the year's shrimp and crab harvests were extremely prosperous; one possible explanation is that runoff from Hurricane Dennis caused marine animals to begin migrating to saltier waters, so they were less vulnerable to Floyd's ill effects.[1] Pollution from runoff was also a significant fear. Numerous pesticides were found in low but measurable quantities in the river waters, particularly in the Neuse River. Overall, however, the concentration of contaminants was slightly lower than had been measured in Hurricane Fran, likely because Floyd simply dropped more water to dilute them.[33]

When the hurricane hit North Carolina, it flooded hog waste lagoons and released 25 million gallons of manure into the rivers, which contaminated the water supply and reduced water quality.[64] Ronnie Kennedy, Duplin County director for environmental health, said that of 310 private wells he had tested for contamination since the storm, 9 percent, or three times the average across eastern North Carolina, had faecal coliform bacteria. Normally, tests showing any hint of faeces in drinking water, an indication that it can be carrying disease-causing pathogens, are cause for immediate action.[65]

See also

- Hurricane Dorian

- Hurricane Florence

- Hurricane Irene

- Hurricane Isaias

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1980–1999)

- List of Pennsylvania hurricanes

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in Massachusetts

- Center for Natural Hazards Research

- Timeline of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season

Notes

- ↑ All wind speeds in the article are maximum sustained winds sustained for one minute, unless otherwise noted.

References

- 1 2 3 Herring, David (2000). "Hurricane Floyd's Lasting Legacy". NASA. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Richard J. Pasch; Todd B. Kimberlain; Stacy R. Stewart (November 18, 1999). "Preliminary Report: Hurricane Floyd" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- 1 2 Lixion Avila (September 8, 1999). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ↑ Jack Beven (September 7, 1999). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (September 8, 1999). Tropical Storm Floyd Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (September 9, 1999). Tropical Storm Floyd Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ↑ James Franklin (September 10, 1999). Hurricane Floyd Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ John L. Guiney (September 13, 1999). Hurricane Floyd Discussion Number 23 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ↑ National Weather Service (2000). "Service Assessment: Hurricane Floyd Floods of September 1999" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "'Very, very dangerous' Floyd heads toward Florida". CNN. September 14, 1999. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Floyd keeps US guessing". BBC News. September 15, 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 National Climatic Data Center (1999). "Climate-Watch, September 1999". NOAA. Archived from the original on October 24, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Kenneth Silber (1999). "Bracing for Impact". space.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Jonathan Lipman (1999). "Storm May Further Jeopardize NASA Budget". space.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Kenneth Silber (1999). "NASA Reports 'Minor' Damage at Space Center". space.com. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Breaking, World, US & Local News – nydailynews.com – NY Daily News". NY Daily News. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ Danielle Hooks (September 8, 2017). "Disney World to close for fifth time in history in preparation for Hurricane Irma". CBS 3. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ↑ Sarah Whitten (September 27, 2022). "Walt Disney World, Universal Studios Orlando to close parks as Hurricane Ian approaches Florida". CNBC. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- 1 2 High Wind Event Report (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- 1 2 3 Hurricane (Typhoon) Event Report (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Heavy Rain Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- 1 2 3 1999-Floyd. Storm Impact Summaries 1999 – 1999 (Report). Environment and Climate Change Canada. September 14, 2010. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ↑ Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ↑ James Franklin (September 10, 1999). Hurricane Floyd Intermediate Advisory Number 11A (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- 1 2 3 Graef, Rick. "The Abacos' Hurricane Floyd Information Pages Relief and Rebuilding Reports and Updates". Go-Abacos.Com. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Wahlstrom, Margareta (1999). "Bahamas: Hurricane Floyd — Preliminary appeal #23/99" (PDF). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (1999). "Battered Bahamas start difficult clean-up in Floyd's wake". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ David Sedore (September 25, 1999). "Floyd's damage to Florida: $50 million". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1B. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections" (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 41 (9). ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Hurricane (Typhoon) Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Hurricane (Typhoon) Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Bales, Jerad D.; Oblinger, Carolyn J.; Sallenger H. Jr., Asbury (2000). "Two Months of Flooding in Eastern North Carolina". USGS. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Flooding in Tarboro and Princeville". Daniel Design Associates. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "The History of Princeville". Town Of Princeville, North Carolina. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ↑ "Landsat Views North Carolina Flood". NASA. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ CNN.com/Sports Illustrated (September 29, 1999). "After the rain". Pirates' big win helps city cope with aftermath of Floyd. CNN. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Unknown. "Summary". North Carolina Floodplain Mapping Hurricane Floyd and 10-Year Disaster Assistance Report. FEMA. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Waters rise, fall across eastern North Carolina". CNN. 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roth, David; Cobb, Hugh. "Virginia Hurricane History". HPC/NOAA. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Hurricane (Typhoon) Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- 1 2 3 David M. Roth. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- 1 2 3 Tropical Storm Event Report (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ Tim Pratt. "Liberty Tree Project Grows". St. John's College.

- ↑ Orioles have experience with hurricanes, NBC Sports, October 28, 2012

- ↑ "Hurricanes that hit Maryland the hardest". Baltimore Business Journal. October 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Maximum Rainfall caused by North Atlantic & Northeast Pacific Tropical Cyclones and their remnants per state (1950–2018)" (GIF). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "2000 Annual Report". New Jersey. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- 1 2 Steve Strunsky (October 17, 1999). "After the Flood; With a Billion of Dollars in Damage, New Jersey Will Be Wringing Out a Long Time". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Risk Assessment" (PDF). State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan (Report). State of New Jersey. Page 5.8-2. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Newman, Andy (September 20, 1999). "Flood Disrupts Bank Machines Across Country". New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Chen, David W. (September 21, 1999). "No Solace in the New Week as the Storm's Legacies Linger". New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Event Record Details for Pennsylvania: High Wind". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (1999). "Event Report for Hurricane Floyd". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Connecticut Event Record Details: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Rhode Island Event Report: Strong Winds". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Massachusetts Event Record Details: Strong Wind". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "New Hampshire Event Record Details: Remnants of Floyd". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "High Wind Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Maine Event Record Details: Remnants of Floyd". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ Régie des assurances agricoles du Québec (September 28, 1999). "Les restes de l'ouragan " Floyd " occasionnent des dommages par excès de vent et de pluie" (pdf). L'État des Cultures Au Québec (in French). Quebec Gouvernment (11). Retrieved August 27, 2011.

- ↑ UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (1999). "Bahamas — Hurricane Floyd OCHA Situation Report No. 2". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Inter-American Development Bank (2000). "IDB approves $21 million to assist Bahamas in rehabilitating works damaged by Hurricane Floyd". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Hog Farming". Duke University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Kilborn, Peter. "Hurricane Reveals Flaws in Farm Law". NY Times.