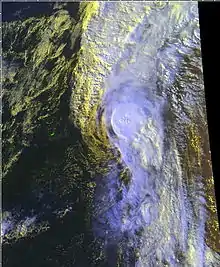

Hurricane Jose over the Lesser Antilles on October 20. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 17, 1999 |

| Dissipated | October 25, 1999 |

| Category 2 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 979 mbar (hPa); 28.91 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 direct |

| Damage | <$5 million (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Jose was the fourteenth tropical cyclone, tenth named storm, and seventh hurricane of the annual hurricane season that caused moderate damage in the Lesser Antilles in October 1999. Jose developed from a tropical wave several hundred miles east of the Windward Islands on October 17. The depression intensified and was subsequently upgraded to Tropical Storm Jose on October 18. The storm tracked northwestward and was upgraded to a hurricane the following day as it approached the northern Leeward Islands. Jose briefly peaked as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) on October 20. However, wind shear weakened the storm back to a Category 1 hurricane before it struck Antigua. Further deterioration occurred and Jose weakened to a tropical storm before landfall in Tortola on October 21. While located north of Puerto Rico on October 22, the storm turned northward, shortly before curving north-northeastward. Wind shear decreased, allowing Jose to re-intensify into a hurricane while passing east of Bermuda on October 24. However, on the following day, wind shear increased again, while sea surface temperatures decreased, causing Jose to weaken and quickly transition into an extratropical cyclone.

The storm brought heavy rainfall to the Lesser Antilles, with some areas experiencing more than 18 inches (460 mm) of precipitation. Despite 15 inches (380 mm) of rain in Anguilla, minimal flooding occurred. However, wind gusts up to 100 mph (160 km/h) uprooted trees, making some roads impassable and damaging houses, crops, and shipping facilities. A combination of hurricane-force winds and flooding in Antigua and Barbuda destroyed at least 500 homes and left 90% of homes without electricity and another 50% experienced disrupted telephone service. Jose also caused 12 injuries and one fatality. Tropical storm force winds in eastern Puerto Rico toppled power lines, trees, and streets signs. Overflow along portions of the Blanco River and landslides caused minor damage. In Saint Kitts and Nevis, mudslides and flooding from the storm caused 1 fatality and impacted several homes and buildings. Flooding and mudslides in Sint Maarten damaged houses and roads, especially in low-lying areas. One death was reported in Sint Maarten. Overall, Jose caused 3 fatalities and damage amounted to near $5 million (1999 USD).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on October 8. The system tracked westward and did not develop further until it was midway between Africa and the Lesser Antilles on October 15. Dvorak satellite classifications began at 1200 UTC on October 17, and six hours later, the system developed into Tropical Depression Fourteen while located about 700 miles (1,100 km) east of the Windward Islands.[1] Initially, the depression had well-defined upper-level outflow, though the low-level circulation was poorly defined.[2] The depression continued to organize, with satellite imagery indicating banding features becoming more well-defined, as a result of an upper-level anticyclone and a westerly jet.[3] It is estimated that the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Jose at 0600 UTC on October 18.[1]

Due to no "immediately identifiable hindrances to further strengthening", intensity forecasts indicated Jose reaching hurricane status by late on October 19.[4] Later that day, three computer models predicted that the anticyclone over Jose would move west-northwestward, causing the storm to potentially strengthen to a major hurricane. However, the National Hurricane Center questioned these forecasts, as the same computer models predicted a similar scenario for Tropical Depression Twelve earlier that month.[5] After t-numbers on the Dvorak scale reached 4.0 and a reconnaissance aircraft flight reported winds of 84 mph (135 km/h), it was estimated that Jose became a hurricane at 1800 UTC on October 19.[6] Early on the following day, cloud tops reached temperatures as low as −121 °F (−85 °C) and the hurricane also developed an eye with a radius of about 34 miles (55 km).[7]

At 0600 UTC on October 20, Jose attained its minimum barometric pressure of 979 mbar (28.9 inHg).[1] Six hours later, the storm strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and reached its maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). Although atmospheric conditions previously seemed favorable for further significant strengthening, water vapor imagery indicated that an upper-trough was extending from the western Caribbean Sea to the eastern Bahamas; this in turn induced wind shear on Jose.[8] Jose weakened immediately after becoming a Category 2 hurricane and winds were 90 mph (150 km/h) when the storm made landfall in Antigua at 1600 UTC on October 21.[1] The National Hurricane Center noted that weakening "may be temporary" and also predicted slow re-intensification.[9][10] However, Jose instead continued to weaken and was only a tropical storm when it made landfall in Tortola at 1105 UTC on October 21. Under the influence of a large mid- to upper-tropospheric trough, Jose curved northward early on October 22, while located north of Puerto Rico.[1] Later on October 22, the storm began re-developing deep convection, though it still maintained a sheared system appearance.[11]

The storm fully recurved to the northeast on October 22, while initially no significant change in intensity occurred. On the following day, the storm began to slowly restrengthen,[1] although wind shear had further exposed the center. As a result, the National Hurricane Center no longer noted the possibility of Jose to re-intensify into a hurricane.[12] Jose began to significantly re-organize on October 24, with deep convection rapidly re-developing around the low-level circulation. Despite this, the National Hurricane Center noted that, "the deep convection is poorly organized enough that strengthening is unlikely before extratropical transition in 36 hours."[13] By 1200 UTC on October 24, the storm once again attained hurricane intensity as it passed about 300 miles (480 km) east of Bermuda.[1] After becoming a hurricane, no further intensification was predicted, as sea surface temperatures would soon decrease.[14] Jose rapidly accelerated and quickly weakened back to a tropical storm by early on October 25. At 1200 UTC on that day, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while located south of Atlantic Canada. Six hours later, the extratropical remnants of Jose merged with a large mid-latitude low.[1]

Preparations

The National Hurricane Center began posting tropical cyclone watches and warnings starting at 0900 UTC on October 18, with a hurricane watch for Barbados. Three hours later, a tropical storm watch was put into effect in Trinidad and Tobago. Late on October 18, a hurricane watch was also issued for Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Lucia, and Dominica, while a tropical storm watch and a warning was extended to include Barbados and Grenada, respectively. At 2100 UTC on October 18, the tropical storm watch that was issued for Trinidad and Tobago was discontinued. Early on October 19, the hurricane watch was extended to include Martinique, Guadeloupe, Antigua, Barbuda, Montserrat, St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla, as well as St. Eustatius, Saba, St. Maarten, St. Martin, and St. Barthelemy shortly thereafter. A hurricane watch in effect for St. Vincent and the Grenadines was soon downgraded to a tropical storm watch; simultaneously, the hurricane watch that was issued for Barbados was canceled. By 0900 UTC on October 19, the hurricane watches in effect for Dominica, Martinique, and Guadeloupe were all upgraded to a hurricane warning. Additionally, the tropical storm watch in Grenada was discontinued.[1]

At 1500 UTC on October 19, the hurricane watch in Dominica, Montserrat, Antigua, Barbuda, Nevis, Saint Kitts, St. Eustatius, Saba, St. Maarten, and Anguilla, was upgraded to a hurricane warning. Simultaneously, a hurricane watch went into effect for the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, while a tropical storm warning was issued for St. Lucia. It was then that the tropical storm watch in St. Vincent and the Grenadines was discontinued. Later on October 19, the hurricane watch previously issued for the Virgin Island and Puerto Rico was upgraded to a hurricane warning. In St. Lucia, the hurricane watch was canceled. At 1200 UTC on October 20, a hurricane warning as put into effect for Desirade, St. Martin, and St. Barthelemy. Throughout the day, the hurricane warnings in Guadeloupe, Dominica, Antigua, and Desirade were discontinued. By 2100 UTC on October 21, all watches and warnings in effect were discontinued.[1]

Twenty-four shelters were set up in Antigua and Barbuda, but only 516 people used the shelters.[15] In Saint Kitts, many tourists were forced to ride out the storm after airports began canceling flights on October 19 and shutting down completely on October 20. Deputy Prime Minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis Sam Condor warned residents to "prepare for the worst". The Governor of the United States Virgin Islands, Charles Wesley Turnbull, issued a curfew effective at 6 p.m. AST on October 20.[16] It was reported on October 20 that 343 shelters would be opened in Puerto Rico, which were stocked with thousands of cots and sleeping bags. Additionally, the police department activated all 18,000 of its officers.[17] The Federal Emergency Management Agency assembled a seven-member Mobilization Center Management Team, with ice and water being pre-staged at Roosevelt Roads Naval Station.[18]

Impact

Anguilla

In Anguilla, tropical storm force winds and rainfall up to 6 inches (150 mm) fell at the Agricultural Department in The Valley.[19] At another location, wind gusts reached 100 mph (160 km/h) and precipitation amounts up to 15 inches (380 mm). As a result, Jose was the wettest tropical cyclone on record in Anguilla, only to be surpassed by Hurricane Lenny about a month later. It also contributed to the rainiest October in Anguilla on record.[20] Winds on the island downed power and telephone lines, however, the electricity had been shut off as the storm was approaching. Additionally, trees uprooted by the winds caused roads to become impassable. Houses, crops, and shipping facilities were also damaged. Rough seas caused significant erosion at many of the famed beaches on the island.[19]

Antigua and Barbuda

In Antigua and Barbuda, there was considerable flooding of major roads and 2,000 people were severely affected and were evacuated. About 516 of the people were housed in emergency shelters.[15] Across the island, the storm killed one person, injured 12, left an elderly blind man missing,[19] and destroyed 500 houses and a newly built church. In the village of Crab's Hill, 64 of the 81 houses were ether seriously damaged or destroyed. The hurricane also disrupted 50% of telephone service and 90% of the homes were left without electricity.[15] A wind gust of 102 mph (164 km/h) was reported by the Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Service on October 20.[21]

Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands

Some areas of Puerto Rico experienced tropical storm force winds, especially the eastern side of the island. The Emergency Management Agency in Luquillo reported sustained winds of 40 to 45 mph (64 to 72 km/h) and gusts up to 55 mph (89 km/h). In San Juan, a sustained winds speed of 23 mph (37 km/h) and a gust of 30 mph (48 km/h) was recorded. A sustained wind speed of 28 mph (45 km/h) and gust up to 37 mph (60 km/h) was measured in Ceiba. Strong winds knocked down power lines, trees, and street signs in Culebra and Fajardo. Rainfall was between 3 and 4 inches (76 and 102 mm) in eastern Puerto Rico,[22] with a peak amount of 6.54 inches (166 mm) in Rio Blanco Lower.[23] The Blanco River overflowed in Naguabo, while landslides were reported in Utuado, Carolina, and Villalba. Damage in Puerto Rico totaled to about $20,000.[22]

In the United States Virgin Islands, tropical storm force winds were measured on at least three islands. On Saint John, a sustained winds speed of 60 mph (97 km/h) and a gust as high as 68 mph (109 km/h) was reported. Sustained winds of 44 mph (71 km/h) and a gust up to 52 mph (84 km/h) was recorded on Saint Thomas. Strong winds caused extensive power outages in Saint Croix, while trees and power lines were felled in Saint Thomas and Saint John. Overall, losses in the United States Virgin Islands reached $20,000.[22]

Saint Martin

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 700.0 | 27.56 | Lenny 1999 | Meteorological Office, Phillpsburg | [24] |

| 2 | 280.2 | 11.03 | Jose 1999 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [25] |

| 3 | 165.1 | 6.50 | Luis 1995 | [26] | |

| 4 | 111.7 | 4.40 | Otto 2010 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [27] |

| 5 | 92.3 | 3.63 | Rafael 2012 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [28] |

| 6 | 51.0 | 2.01 | Laura 2020 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [29] |

| 7 | 42.6 | 1.68 | Isaias 2020 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [30] |

| 8 | 7.9 | 0.31 | Ernesto 2012 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [28] |

| 9 | 7.0 | 0.28 | Chantal 2013 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [31] |

| 10 | 6.6 | 0.26 | Dorian 2013 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [31] |

On the French side of the island, Saint Martin, torrential rainfall was recorded. In Marigot, precipitation reached 19.6 inches (500 mm) in 48 hours between late on October 20 and October 22. Sustained winds of the island were slightly less than 62 mph (100 km/h) and gusts were under 93 mph (150 km/h). Storm surges in coastal areas was mostly between 2.9 and 3.6 feet (0.88 and 1.10 m) above normal.[32] In Sint Maarten, which is the Dutch portion of the island, sustained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h) and a gust to 100 mph (160 km/h) were reported at the Princess Juliana International Airport, while a rainfall total of 13.75 inches (349 mm) was observed in Pointe Blanche. Flooding and mudslides caused by the heavy precipitation damaged roads and homes, especially in low-lying areas. In addition to the flood damage, one fatality was reported in Sint Maarten.[1]

Rest of Caribbean

In St. Kitts and Nevis, rainfall caused flooding, which washed out several main roads and resulted in landslides were reported. Several buildings and roads suffered damage and one person was reported have perished due to the storm's ferocity.[1] Dominica received no more than a little rain, only being persistent for one morning.[33] On Saint Barthélemy, rainfall exceeded 15 inches (380 mm) in a 48‑hour period. During the overall 60‑hour period, precipitation amounts reached 16.5 inches (420 mm). At another location, Flamands, rainfall reached 17.6 inches (450 mm) in only 48 hours. In the capital city of Gustavia, a sustained winds speed of 62 mph (100 km/h) and a gust up to 74 mph (119 km/h). Later, another wind gust of 93 mph (150 km/h) was recorded before the anemometer failed. Along the shore, tides reached 3.3 feet (1.0 m) above normal.[32] In Montserrat, the storm brought winds up to 45 mph (72 km/h). A small number of down trees caused power outages in one area, though it electricity was restored within an hour. Only a few landslides occurred, while volcanic mudflow poured down Soufrière Hills, but no damage occurred.[34]

Aftermath

Immediately following the storm, an Emergency Operation Centre was established in St. John's by the Antigua & Barbuda Red Cross Society in St. John's. In the first week after the storm, 35 Red Cross volunteers distributed 1,500 tarpaulins, 210 blankets, 300 food parcels, and 30 hurricane lamps to residents in the effected communities of York's, Villa, Greens Bay, Perry Bay, Piggotts, Bendals Bolans, Crab's Hill, Urlings, St. John's, and Jennings. a Red Cross office in St. Vincent de Paul also distributed rice and beans to 2,000 people, while the National office of Disaster Services provided plastic sheeting and water bottles. The Government of Antigua and Barbuda dispatched teams to re-open roads, clean up debris, and restore utilities. However, after Hurricane Lenny struck the Lesser Antilles about a month later, relief efforts slowed, as many more people were significantly affected, causing recovery to be costlier.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Richard J. Pasch (November 22, 1999). Preliminary Report Hurricane Jose 17 – 25 October 1999 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 17, 1999). Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Richard J. Pasch (October 18, 1999). Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ John P. Guiney (October 18, 1999). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (October 19, 1999). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (October 19, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (October 20, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 20, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 20, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ James L. Franklin (October 21, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 22, 1999). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 20 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ James L. Franklin (October 23, 1999). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 23 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (October 24, 1999). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 26 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Richard J. Pasch (October 24, 1999). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 28 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Margareta Wahlström & George Weber (November 3, 1999). Antigua and Barbuda: Hurricane Jose (PDF) (Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Jose strikes Antigua head-on, threatens other islands". The Post and Courier. Associated Press. October 21, 1999. p. 5. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Reuters (October 20, 1999). Hurricane Jose hammers Antigua, heads towards V.I. (Report). ReliefWeb. Colin James. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

{{cite report}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ↑ Federal Emergency Management Agency (October 20, 1999). Officials Prepare for Hurricane Jose (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (October 21, 1999). Hurricane Jose Post Impact Situation Report #2 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Historical Tropical Cyclone (Hurricane) Information for Anguilla from 1955-2000". World-Weather-Travellers-Guide.com. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 20, 1999). Hurricane Jose Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). Caribbean Hurricane Network. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Stephen Greco. Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena With Late Reports and Correction (PDF) (Report). National Climatic Data Center. pp. 56 and 63. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ↑ David M. Roth (May 4, 2006). Hurricane Jose - October 20-24, 1999 (PDF) (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ↑ Guiney, John L (December 9, 1999). Preliminary Report: Hurricane Lenny November 13 - 23, 1999 (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard J; National Hurricane Center (November 22, 1999). Hurricane Jose: October 17 - 25, 1999 (Preliminary Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles B; National Hurricane Center (January 8, 1996). Hurricane Luis: August 27 - September 11, 1995 (Preliminary Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ↑ Cangialosi, John P; National Hurricane Center (November 17, 2010). Hurricane Otto October 6 - 10 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 6-7. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- 1 2 Connor, Desiree; Etienne-LeBlanc, Sheryl (January 2013). Climatological Summary 2012 (PDF) (Report). Meteorological Department St. Maarten. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.meteosxm.com/wp-content/uploads/Climatological-Summary-2020.pdf

- ↑ http://www.meteosxm.com/wp-content/uploads/Climatological-Summary-2020.pdf

- 1 2 2013 Atlantic Hurricane Season Summary Chart (PDF) (Report). Meteorological Department St. Maarten. January 2013. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- 1 2 (in French) Compte Rendu Meteorologique Passage de l'Ouragan Jose (Report). Météo-France. October 27, 1999. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Hurricane Jose". avirtualDominica.com. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Denis Chabrol (1999). "Jose Barely Grazes Montserrat". Montserrat Report. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Antigua & Barbuda - Hurricane Jose" (PDF). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. July 9, 2002. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

External links

- Antigua and Barbuda Damage report

- Jose report

- BBC News

- Jose Damage report

- Irish Examiner

- The Prime Minister of Antigua's address to the nation about Jose