| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Hyi |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Hydri |

| Pronunciation | /ˈhaɪdrəs/, genitive /ˈhaɪdraɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the water snake |

| Right ascension | 00h 06.1m to 04h 35.1m [1] |

| Declination | −57.85° to −82.06°[1] |

| Quadrant | SQ1 |

| Area | 243 sq. deg. (61st) |

| Main stars | 3 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 19 |

| Stars with planets | 4 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 2 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 1 |

| Brightest star | β Hyi (2.82m) |

| Messier objects | none |

| Meteor showers | none |

| Bordering constellations | Dorado Eridanus Horologium Mensa Octans Phoenix (corner) Reticulum Tucana |

| Visible at latitudes between +8° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of November. | |

Hydrus /ˈhaɪdrəs/ is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm (14 in) diameter celestial globe published in late 1597 (or early 1598) in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. The French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille charted the brighter stars and gave their Bayer designations in 1756. Its name means "male water snake", as opposed to Hydra, a much larger constellation that represents a female water snake. It remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers.

The brightest star is the 2.8-magnitude Beta Hydri, also the closest reasonably bright star to the south celestial pole. Pulsating between magnitude 3.26 and 3.33, Gamma Hydri is a variable red giant 60 times the diameter of the Sun. Lying near it is VW Hydri, one of the brightest dwarf novae in the heavens. Four star systems in Hydrus have been found to have exoplanets to date, including HD 10180, which could bear up to nine planetary companions.

History

Hydrus was one of the twelve constellations established by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius from the observations of the southern sky by the Dutch explorers Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, who had sailed on the first Dutch trading expedition, known as the Eerste Schipvaart, to the East Indies. It first appeared on a 35-cm (14 in) diameter celestial globe published in late 1597 (or early 1598) in Amsterdam by Plancius with Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in the German cartographer Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603.[2][3] De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue the same year under the Dutch name De Waterslang, "The Water Snake",[4] it representing a type of snake encountered on the expedition rather than a mythical creature.[5] The French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille called it l’Hydre Mâle on the 1756 version of his planisphere of the southern skies, distinguishing it from the feminine Hydra. The French name was retained by Jean Fortin in 1776 for his Atlas Céleste, while Lacaille Latinised the name to Hydrus for his revised Coelum Australe Stelliferum in 1763.[6]

Characteristics

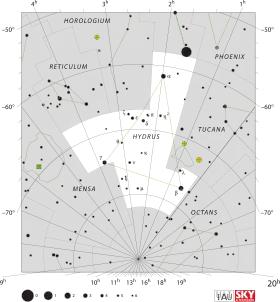

Irregular in shape,[7] Hydrus is bordered by Mensa to the southeast, Eridanus to the east, Horologium and Reticulum to the northeast, Phoenix to the north, Tucana to the northwest and west, and Octans to the south; Lacaille had shortened Hydrus' tail to make space for this last constellation he had drawn up.[5] Covering 243 square degrees and 0.589% of the night sky, it ranks 61st of the 88 constellations in size.[8] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Hyi".[9] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 12 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 00h 06.1m and 04h 35.1m , while the declination coordinates are between −57.85° and −82.06°.[1] As one of the deep southern constellations, it remains below the horizon at latitudes north of the 30th parallel in the Northern Hemisphere, and is circumpolar at latitudes south of the 50th parallel in the Southern Hemisphere.[7] Herman Melville mentions it and Argo Navis in Moby Dick "beneath effulgent Antarctic Skies", highlighting his knowledge of the southern constellations from whaling voyages.[10] A line drawn between the long axis of the Southern Cross to Beta Hydri and then extended 4.5 times will mark a point due south.[11] Hydrus culminates at midnight around 26 October.[12]

Features

Stars

Keyzer and de Houtman assigned fifteen stars to the constellation in their Malay and Madagascan vocabulary, with a star that would be later designated as Alpha Hydri marking the head, Gamma the chest and a number of stars that were later allocated to Tucana, Reticulum, Mensa and Horologium marking the body and tail.[13] Lacaille charted and designated 20 stars with the Bayer designations Alpha through to Tau in 1756. Of these, he used the designations Eta, Pi and Tau twice each, for three sets of two stars close together, and omitted Omicron and Xi. He assigned Rho to a star that subsequent astronomers were unable to find.[14]

Beta Hydri, the brightest star in Hydrus, is a yellow star of apparent magnitude 2.8, lying 24 light-years from Earth.[15] It has about 104% of the mass of the Sun and 181% of the Sun's radius, with more than three times the Sun's luminosity.[16] The spectrum of this star matches a stellar classification of G2 IV, with the luminosity class of 'IV' indicating this is a subgiant star. As such, it is a slightly more evolved star than the Sun, with the supply of hydrogen fuel at its core becoming exhausted. It is the nearest subgiant star to the Sun and one of the oldest stars in the solar neighbourhood. Thought to be between 6.4 and 7.1 billion years old, this star bears some resemblance to what the Sun may look like in the far distant future, making it an object of interest to astronomers.[16] It is also the closest bright star to the south celestial pole.[7]

Located at the northern edge of the constellation and just southwest of Achernar is Alpha Hydri,[17] a white sub-giant star of magnitude 2.9, situated 72 light-years from Earth.[18] Of spectral type F0IV,[19] it is beginning to cool and enlarge as it uses up its supply of hydrogen. It is twice as massive and 3.3 times as wide as the Sun and 26 times more luminous.[18] A line drawn between Alpha Hydri and Beta Centauri is bisected by the south celestial pole.[12]

In the southeastern corner of the constellation is Gamma Hydri,[7] a red giant of spectral type M2III located 214 light-years from Earth.[20] It is a semi-regular variable star, pulsating between magnitudes 3.26 and 3.33. Observations over five years were not able to establish its periodicity.[21] It is around 1.5 to 2 times as massive as the Sun, and has expanded to about 60 times the Sun's diameter. It shines with about 655 times the luminosity of the Sun.[22] Located 3° northeast of Gamma is the VW Hydri, a dwarf nova of the SU Ursae Majoris type. It is a close binary system that consists of a white dwarf and another star, the former drawing off matter from the latter into a bright accretion disk. These systems are characterised by frequent eruptions and less frequent supereruptions. The former are smooth, while the latter exhibit short "superhumps" of heightened activity.[23] One of the brightest dwarf novae in the sky,[24] it has a baseline magnitude of 14.4 and can brighten to magnitude 8.4 during peak activity.[23] BL Hydri is another close binary system composed of a low-mass star and a strongly magnetic white dwarf. Known as a polar or AM Herculis variable, these produce polarized optical and infrared emissions and intense soft and hard X-ray emissions to the frequency of the white dwarf's rotation period—in this case 113.6 minutes.[25]

There are two notable optical double stars in Hydrus. Pi Hydri, composed of Pi1 Hydri and Pi2 Hydri, is divisible in binoculars.[7] Around 476 light-years distant,[26] Pi1 is a red giant of spectral type M1III that varies between magnitudes 5.52 and 5.58.[27] Pi2 is an orange giant of spectral type K2III and shining with a magnitude of 5.7, around 488 light-years from Earth.[28]

Eta Hydri is the other optical double, composed of Eta1 and Eta2.[7] Eta1 is a blue-white main sequence star of spectral type B9V that was suspected of being variable,[29] and is located just over 700 light-years away.[30] Eta2 has a magnitude of 4.7 and is a yellow giant star of spectral type G8.5III around 218 light-years distant,[31] which has evolved off the main sequence and is expanding and cooling on its way to becoming a red giant. Calculations of its mass indicate it was most likely a white A-type main sequence star for most of its existence, around twice the mass of the Sun. A planet, Eta2 Hydri b, greater than 6.5 times the mass of Jupiter was discovered in 2005, orbiting around Eta2 every 711 days at a distance of 1.93 astronomical units (AU).[32]

Three other systems have been found to have planets, most notably the Sun-like star HD 10180, which has seven planets, plus possibly an additional two for a total of nine—as of 2012 more than any other system to date, including the Solar System.[33] Lying around 127 light-years (39 parsecs) from the Earth,[34] it has an apparent magnitude of 7.33.[35]

GJ 3021 is a solar twin—a star very like the Sun—around 57 light-years distant with a spectral type G8V and magnitude of 6.7.[36] It has a Jovian planet companion (GJ 3021 b). Orbiting about 0.5 AU from its star, it has a minimum mass 3.37 times that of Jupiter and a period of around 133 days.[37] The system is a complex one as the faint star GJ 3021B orbits at a distance of 68 AU; it is a red dwarf of spectral type M4V.[38]

HD 20003 is a star of magnitude 8.37. It is a yellow main sequence star of spectral type G8V a little cooler and smaller than the Sun around 143 light-years away. It has two planets that are around 12 and 13.5 times as massive as the Earth with periods of just under 12 and 34 days respectively.[39]

Deep-sky objects

Hydrus contains only faint deep-sky objects. IC 1717 was a deep-sky object discovered by the Danish astronomer John Louis Emil Dreyer in the late 19th century. The object at the coordinate Dreyer observed is no longer there, and is now a mystery. It was very likely to have been a faint comet.[40] PGC 6240, known as the White Rose Galaxy, is a giant spiral galaxy surrounded by shells resembling rose petals, located around 345 million light years from the Solar System. Unusually, it has cohorts of globular clusters of three distinct ages suggesting bouts of post-starburst formation following a merger with another galaxy.[41] The constellation also contains a spiral galaxy, NGC 1511, which lies edge on to observers on Earth and is readily viewed in amateur telescopes.[12]

Located mostly in Dorado, the Large Magellanic Cloud extends into Hydrus.[42] The globular cluster NGC 1466 is an outlying component of the galaxy, and contains many RR Lyrae-type variable stars. It has a magnitude of 11.59 and is thought to be over 12 billion years old.[43] Two stars, HD 24188 of magnitude 6.3 and HD 24115 of magnitude 9.0, lie nearby in its foreground.[12] NGC 602 is composed of an emission nebula and a young, bright open cluster of stars that is an outlying component on the eastern edge of the Small Magellanic Cloud,[44] a satellite galaxy to the Milky Way. Most of the cloud is located in the neighbouring constellation Tucana.[45]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Hydrus, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Johann Bayer's Southern Star Chart". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ "Hydrus (Water Snake)". Chandra X-ray Observatory. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- 1 2 Ridpath, Ian. "Hydrus—the Lesser Water Snake". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille's Southern Planisphere of 1756". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1991). The Constellations: An Enthusiast's Guide to the Night Sky. London, United Kingdom: Aurum Press. pp. 385, 391. ISBN 978-1-85410-088-7.

- ↑ Bagnall, Philip M. (2012). The Star Atlas Companion: What You Need to Know about the Constellations. New York City: Springer. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-4614-0830-7.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Brett (1998). Herman Melville: Stargazer. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 5. ISBN 978-0-7735-1786-8.

- ↑ Stilwell. Alexander (2010). Crisis Survival. SAS and Elite Forces Survival Guide. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-908696-06-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Malin, David; Frew, David J. (1995). Hartung's Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes: A Handbook for Amateur Observers. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-521-55491-6.

- ↑ Knobel, Edward B. (1917). "On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77 (5): 414–32 [422]. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..414K. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.5.414.

- ↑ Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, VA: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 176–77. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ↑ "Beta Hydri". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- 1 2 Brandão, I. M.; Doğan, G.; Christensen-Dalsgaard, J.; Cunha, M. S.; Bedding, T. R.; Metcalfe, T. S.; Kjeldsen, H.; Bruntt, H.; et al. (March 2011). "Asteroseismic Modelling of the Solar-type Subgiant Star β Hydri". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 527: A37. arXiv:1012.3872. Bibcode:2011A&A...527A..37B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015370. S2CID 37441284.

- ↑ Moore, Patrick (2005). The Observer's Year: 366 Nights of the Universe (2nd ed.). New York City: Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-85233-884-8.

- 1 2 Kaler, Jim. "Alpha Hydri". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "LTT 1059—High Proper-motion Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "Gamma Hydri—Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Tabur, V.; Bedding, T. R.; Kiss, L. L.; Moon, T. T.; Szeidl, B.; Kjeldsen, H. (2009). "Long-term Photometry and Periods for 261 Nearby Pulsating M Giants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 400 (4): 1945–61. arXiv:0908.3228. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.400.1945T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15588.x. S2CID 15358380.

- ↑ Kaler, Jim. "Gamma Hydri". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- 1 2 BSJ (19 July 2010). "VW Hydri". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Vogt, N. (1974). "Photometric Study of the Dwarf Nova VW Hydri". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 36: 369–78. Bibcode:1974A&A....36..369V.

- ↑ Middleditch, John; Imamura, James N.; Steiman-Cameron, Thomas Y. (1997). "Discovery of Quasi-periodic Oscillations in the AM Herculis Object BL Hydri". Astrophysical Journal. 489 (2): 912–16. Bibcode:1997ApJ...489..912M. doi:10.1086/304834.

- ↑ "HR 667". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "NSV 767". International Variable Star Index. AAVSO. 18 January 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "HR 678". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "Eta1 Hydri". International Variable Star Index. AAVSO. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "Eta 1Hydri—Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "HR 570—Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Setiawan, J.; Rodmann, J.; Da Silva, L.; Hatzes, A. P.; Pasquini, L.; Von Der Lühe, O.; De Medeiros, J. R.; Döllinger, M. P.; et al. (2005). "A Substellar Companion Around the Intermediate-mass Giant star HD 11977". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 437 (2): L31–L34. arXiv:astro-ph/0505510. Bibcode:2005A&A...437L..31S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500133. S2CID 6362483.

- ↑ Tuomi, Mikko (April 2012). "Evidence for 9 planets in the 10180 system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: A52. arXiv:1204.1254. Bibcode:2012A&A...543A..52T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118518. S2CID 15876919.

- ↑ Gill, Victoria (24 August 2010). "Rich exoplanet system discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ "HD 10180—Star". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "HD 1237—Pre-main sequence Star". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ Naef, D.; Mayor, M.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D.; Santos, N. C.; Udry, S.; Burnet, M. (2001). "The CORALIE survey for southern extrasolar planets V. 3 new extrasolar planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 375 (1): 205–18. arXiv:astro-ph/0106255. Bibcode:2001A&A...375..205N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010841. S2CID 16606841.

- ↑ Chauvin, G.; Lagrange, A.-M.; Udry, S.; Mayor, M. (2007). "Characterization of the Long-period Companions of the Exoplanet Host Stars: HD 196885, HD 1237 and HD 27442". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 475 (2): 723–27. arXiv:0710.5918. Bibcode:2007A&A...475..723C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20067046. S2CID 16950822.

- ↑ Brandão, I. M.; Dogan, G.; Christensen-Dalsgaard, J.; Cunha, M. S.; Bedding, T. R.; Metcalfe, T. S.; Kjeldsen, H.; Bruntt, H.; Arentoft, T. (2011). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XXXIV. Occurrence, mass distribution and orbital properties of super-Earths and Neptune-mass planets". arXiv:1109.2497 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ Bagnall, Philip M. (2012). The Star Atlas Companion: What You Need to Know about the Constellations. New York City: Springer. pp. 251–52. ISBN 978-1-4614-0830-7.

- ↑ Maybhate, Aparna; Goudfrooij, Paul; Schweizer, François; Puzia, Thomas; Carter, David (2007). "Evidence for Three Subpopulations of Globular Clusters in the Early-Type Poststarburst Shell Galaxy AM". Astronomical Journal. 1729. 134 (5): 139–655. arXiv:0707.3133. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.1729M. doi:10.1086/521817. S2CID 12557470.

- ↑ Ellyard, David; Tirion, Wil (2008) [1993]. The Southern Sky Guide (3rd ed.). Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-521-71405-1.

- ↑ Westerlund, Bengt E. (1997). "The Age Distribution of Cloud Clusters". The Magellanic Clouds. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-521-48070-3.

- ↑ Bakich, Michael E. (2010). 1001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die: The Best Sky Objects for Star Gazers. New York City: Springer. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-4419-1777-5.

- ↑ Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.

External links

- Chandra information about Hydrus

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Hydrus

- The clickable Hydrus