Telescopium Herschelii (Latin for Herschel's telescope), also formerly known as Tubus Hershelli Major, is a former constellation in the northern celestial hemisphere. Maximilian Hell established it in 1789 to honour Sir William Herschel's discovery of the planet Uranus. It fell out of use by the end of the 19th century. θ Geminorum at apparent magnitude 4.8 was the constellation's brightest star.

History

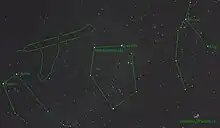

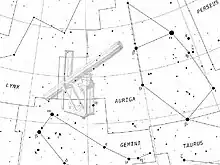

It was one of two constellations created by Maximilian Hell in 1789 to honour the famous English astronomer Sir William Herschel's discovery of the planet Uranus.[1] Named Tubus Hershelli Major by Hell, it was located in the constellation Auriga near the border to Lynx and Gemini and depicted Herschel's 20-ft-long telescope. Its sibling was Tubus Hershelli Minor, which lay between Orion and Taurus. The two telescopes lay near Zeta Tauri, near where the planet Uranus was first spotted.[1]

Johann Elert Bode renamed the constellation Telescopium Herschelii and omitted the smaller telescope constellation in his 1801 Uranographia star atlas. In his atlas, the constellation depicted Herschel's earlier 7-foot telescope.[1] It was ignored by some celestial cartographers such as Argelander in 1843, Proctor in 1876, Rosser in 1879 and Pritchard in 1885, yet did appear in two works of the 1890s. However, it was noted by Allen in 1899 that it was becoming obsolete. In 1930, when the official borders of the constellations were drawn up, its stars were absorbed into Auriga, Gemini and Lynx.[2]

Stars

ψ2 Aurigae (also known as 50 Aurigae), with an apparent magnitude of 4.8, was the second-brightest star in the constellation, Bode assigning it the designation 'a'.[1] Located 420 ± 20 light-years distant from earth,[3] it is an orange giant of spectral type K3III.[4], although the magnitude 3.60 star θ Geminorum is brighter. Other stars belonging to the constellation include ψ4, ψ5, ψ7, ψ8, ψ9, 63, 64, 65 and 66 Aurigae, and o Geminorum.

Thought to be around 4 billion years old, ψ5 Aurigae is a sunlike star of spectral type G0V that is around 1.07 times as massive as the Sun and 1.18 times as wide.[5] It appears to have a circumstellar disk of dust, known as a debris disk.[6]

List

This is the list of notable stars in the obsolete constellation Telescopium Herschelii, sorted by decreasing brightness.

| Name | B | F | Var | HD | HIP | RA | Dec | vis. mag. |

abs. mag. |

Dist. (ly) | Sp. class | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ Gem | θ | 34 | 50019 | 33018 | 06h 52m 47.34s | +33° 57′ 40.9″ | 3.60 | −0.30 | 197 | A3III | ||

| ψ2 Aur | ψ2 Aur / a | 50 Aur | 47174 | 31832 | 06h 39m 19.83s | +42° 29′ 20.4″ | 4.80 | −0.81 | 432 | K3III | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | |

| ο Gem | ο Gem | 71 Gem | 61110 | 37265 | 07h 39m 09.96s | +34° 35′ 04.7″ | 4.89 | 1.46 | 158 | F3III | Jishui | |

| ψ10 Aur | ψ10 Aur | 16 Lyn | 50973 | 33485 | 06h 57m 37.12s | +45° 05′ 38.8″ | 4.90 | 0.71 | 225 | A2Vn | suspected variable, part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | |

| 63 Aur | 63 Aur | 54716 | 34752 | 07h 11m 39.29s | +39° 19′ 14.0″ | 4.91 | −0.86 | 464 | K4II-III | |||

| ψ7 Aur | ψ7 Aur | 58 Aur | 49520 | 32844 | 06h 50m 45.96s | +41° 46′ 53.6″ | 4.99 | −0.25 | 364 | K3III | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | |

| ψ4 Aur | ψ4 Aur | 55 Aur | 47914 | 32173 | 06h 43m 05.01s | +44° 31′ 28.3″ | 5.04 | 0.18 | 306 | K5III | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | |

| 65 Aur | 65 Aur | 57264 | 35710 | 07h 22m 02.69s | +36° 45′ 38.3″ | 5.12 | 0.84 | 235 | K0III | |||

| π Gem | π Gem | 80 Gem | 62898 | 38016 | 07h 47m 30.34s | +33° 24′ 56.8″ | 5.14 | −1.04 | 562 | M0III | suspected variable, ΔV = 0.08m | |

| 66 Aur | 66 Aur | 57669 | 35907 | 07h 24m 08.47s | +40° 40′ 20.8″ | 5.23 | −1.51 | 728 | K0III | |||

| ψ5 Aur | ψ5 Aur | 56 Aur | 48682 | 32480 | 06h 46m 44.34s | +43° 34′ 37.3″ | 5.24 | 4.15 | 54 | G0V | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | |

| 64 Aur | 64 Aur | 56221 | 35341 | 07h 18m 02.22s | +40° 53′ 00.1″ | 5.87 | 1.30 | 268 | A5Vn | |||

| ψ9 Aur | ψ9 | 50658 | 33377 | 06h 56m 32.06s | +46° 16′ 26.4″ | 5.85 | −1.17 | 825 | B8III | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] | ||

| ψ8 Aur | ψ8 | 61 Aur | 50204 | 33133 | 06h 53m 57.07s | +38° 30′ 18.3″ | 6.46 | −0.56 | 825 | B9.5sp... | part of Dolones (ψ Aur)[7] |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Ridpath, Ian. "Telescopium Herschelii". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Barentine, John C. (2015). The Lost Constellations: A History of Obsolete, Extinct, or Forgotten Star Lore. New York, New York: Springer. p. 421. ISBN 9783319227955.

- ↑ van Leeuwen, Floor (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 474 (2): 653–664, arXiv:0708.1752v1, Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, S2CID 18759600. Note: see VizieR catalogue I/311.

- ↑ "50 Aur". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Takeda, Genya; Ford, Eric B.; Sills, Alison; Rasio, Frederic A.; Fischer, Debra A.; Valenti, Jeff A. (February 2007). "Structure and Evolution of Nearby Stars with Planets. II. Physical Properties of ~1000 Cool Stars from the SPOCS Catalog". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 168 (2): 297–318. arXiv:astro-ph/0607235. Bibcode:2007ApJS..168..297T. doi:10.1086/509763. S2CID 18775378.

- ↑ Rodriguez, David R.; Zuckerman, B. (February 2012). "Binaries among Debris Disk Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 745 (2): 147. arXiv:1111.5618. Bibcode:2012ApJ...745..147R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/745/2/147. S2CID 73681879.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ESA (1997). "The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues". Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- Kostjuk, N. D. (2002). "HD-DM-GC-HR-HIP-Bayer-Flamsteed Cross Index". Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- Roman, N. G. (1987). "Identification of a Constellation from a Position". Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2004). "Combined General Catalogue of Variable Stars (GCVS4.2)". Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2012). "General Catalog of Variable Stars (GCVS database, version 2012Feb)". Retrieved 2012-04-03.