| Ice hockey at the Olympic Games | |

|---|---|

| |

| IOC Discipline Code | IHO |

| Governing body | IIHF |

| Events | 2 (men: 1; women: 1) |

| Games | |

| |

Ice hockey tournaments have been staged at the Olympic Games since 1920. The men's tournament was introduced at the 1920 Summer Olympics and was transferred permanently to the Winter Olympic Games program in 1924, in France. The women's tournament was first held at the 1998 Winter Olympics.

The Olympic Games were originally intended for amateur athletes. However, the advent of the state-sponsored "full-time amateur athlete" of the Eastern Bloc countries further eroded the ideology of the pure amateur, as it put the self-financed amateurs of the Western countries at a disadvantage. The Soviet Union entered teams of athletes who were all nominally students, soldiers, or working in a profession, but many of whom were in reality paid by the state to train on a full-time basis.[1] In 1986, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) voted to allow professional athletes to compete in the Olympic Games starting in 1988. The National Hockey League (NHL) was initially reluctant to allow its players to compete because the Olympics are held in the middle of the NHL season, and the league would have to halt play if many of its players participated. Eventually, NHL players were admitted starting in 1998.[2]

From 1924 to 1988, the tournament started with a round-robin series of games and ended with the medal round. Medals were awarded based on points accumulated during that round. In 1992, the playoffs were introduced for the first time since 1920. In 1998, the format of the tournament was adjusted to accommodate the NHL schedule; a preliminary round was played without NHL players or the top six teams—Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Russia, Sweden and the United States—followed by a final round which included them. The tournament format was changed again in 2006; every team played five preliminary games with the full use of NHL players.

The games of the tournament follow the rules of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), which differ slightly from the rules used in the NHL. In the men's tournament, Canada was the most successful team of the first three decades, winning six of seven gold medals from 1924 to 1952. Czechoslovakia, Sweden and the United States were also competitive during this period and won multiple medals. Between 1920 and 1968, the Olympic hockey tournament was also counted as the Ice Hockey World Championship for that year. The Soviet Union first participated in 1956 and overtook Canada as the dominant international team, winning seven of the nine tournaments in which they participated. The United States won gold medals in 1960 and in 1980, which included their "Miracle on Ice" upset of the Soviet Union. Canada went 50 years without a gold medal, before winning one in 2002, and following it with back-to-back wins in 2010 and 2014. Other nations to win gold include Great Britain in 1936, the Unified Team in 1992, Sweden in 1994 and 2006, the Czech Republic in 1998, Russia (as OAR) in 2018 and Finland in 2022. Other medal-winning nations include Switzerland, Germany and Slovakia.

In July 1992, the IOC voted to approve women's hockey as an Olympic event; it was first held at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano. The Nagano Organizing Committee was hesitant to include the event because of the additional costs of staging the tournament, but an agreement was reached that limited the field to six teams, and ensured that no additional facilities would be built. The Canadian teams have dominated the event. The United States won the first tournament in 1998 and in 2018. Canada has won all of the other tournaments (2002–2014, 2022).

Inception as an Olympic sport

The first Olympic ice hockey tournament took place at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium.[3] At the time, organized international ice hockey was still relatively new.[4] The International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), the sport's governing body, was created on 15 May 1908, and was known as the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace (LIHG) until 1947.[5] At the 1914 Olympic Congress in Paris, ice hockey was added to the list of optional sports that Olympics organizers could include.[6] The decision to include ice hockey for the 1920 Summer Olympics was made in January, three months before the start of the Games.[7] Several occurrences led to the sport's inclusion in the programme. Five European nations had committed to participating in the tournament and the managers of Antwerp's Palais de Glace stadium refused to allow the building to be used for figure skating unless ice hockey was included.[7] The IIHF considers the 1920 tournament to be the first Ice Hockey World Championship. From then on, the two events occurred concurrently, and every Olympic tournament until 1968 is counted as the World Championship.[8] The Olympic Games were originally intended for amateur athletes, so the players of the National Hockey League (NHL) and other professional leagues were not allowed to play.[9]

The first Winter Olympic Games were held in 1924 in Chamonix, France.[10] Chapter 1, article 6, of the 2007 edition of the Olympic Charter defines winter sports as "sports which are practised on snow or ice".[11] Ice hockey and figure skating were permanently integrated in the Winter Olympics programme.[12] The IOC made the Winter Games a permanent fixture and they were held the same year as the Summer Games until 1992. Following that, further Winter Games have been held on the third year (i.e. 1994, 1998, etc.) of each Olympiad.[13]

History of events

| Event | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 48 | 52 | 56 | 60 | 64 | 68 | 72 | 76 | 80 | 84 | 88 | 92 | 94 | 98 | 02 | 06 | 10 | 14 | 18 | 22 | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men's tournament | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 25 |

| Women's tournament | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total events | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

Men's tournament

1920 Summer Olympics

The men's tournament held at the 1920 Summer Olympics was organized by a committee that included future LIHG president Paul Loicq. The tournament used the Bergvall System, in which three rounds were played.[14] The first round was an elimination tournament that determined the gold medal winner. The second round consisted of the teams that were defeated by the gold medal winner; the winner of that round was awarded the silver medal. The final round was played between teams that had lost to the gold or silver medal winners; the winner of that round received the bronze medal.[15]

The tournament was played from 23 to 29 April and seven teams participated: Canada, Czechoslovakia, the United States, Switzerland, Sweden, France and Belgium. Canada chose to send the Allan Cup-winning Winnipeg Falcons. The Swedish team consisted of mostly bandy players, many of whom had only started playing hockey in preparation for the tournament.[15] Canadian team manager W. A. Hewitt refereed the first game played, an 8–0 win by Sweden versus Belgium.[16]

Canada won all three of the team's games in the first round and won the gold medal, defeating Sweden in the final and outscoring opponents 27–1.[17] In the two subsequent rounds, the United States and Czechoslovakia won the silver and bronze medals respectively.[18] The Bergvall System was criticized, especially in Sweden, because the Swedish team had to play six games (winning three) while the bronze medal-winning Czech team only had to play three (winning one). Erik Bergvall, the creator of the system, stated that it was used incorrectly and that a tournament of all of the losing teams from the first round should have been played for the silver medal.[15] Because of these criticisms, the Bergvall System was not used again for ice hockey.[15]

1924–1936

In 1924, the tournament was played in a round-robin format, consisting of a preliminary round and a medal round. The medals were awarded based on win–loss records during the medal round.[19] This format was used until 1988, although the number of teams and games played varied slightly. The Toronto Granites, representing Canada, became one of the dominant hockey teams in Olympic history, outscoring opponents 110–3, led by Harry Watson, who scored 36 goals.[20] The United States won silver and Great Britain won bronze.[21] Watson's 36 goals remains the tournament record for career goals. He also set the record for career points with 36 (assists were not counted at the time), which stood until 2010.[22]

Eleven teams participated in the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland. The Canadian team was given a bye to the medal round and won all of its games by a combined score of 38–0.[23] The Swedish and Swiss teams won their first medals—silver and bronze respectively—and a German team participated for the first time, finishing ninth.[24] At the 1932 Winter Olympics, Canada won gold in a tournament that consisted of four teams that played each other twice.[25] Germany won bronze, the nation's first medal in the sport.[26]

Two days before the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, Canadian officials protested that two players on the British team—James Foster and Alex Archer—had played in Canada but transferred without permission to play for clubs in the English National League. The IIHF agreed with Canada, but Great Britain threatened to withdraw the team if the two were barred from competing. To avoid a conflict, Canada withdrew the protest shortly before the Games began. The tournament consisted of four groups and fifteen teams. Great Britain became the first non-Canadian team to win gold; Canada won silver and the United States bronze.[27]

Challenges to the definition of amateur

The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) revised its definition of amateur and broke away from the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada in 1936, despite the possibility that its players may no longer be eligible for Olympic hockey.[28] Tommy Lockhart founded the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States (AHAUS) in 1937, after disagreements with the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States over international amateurs.[29][30] The CAHA and the AHAUS joined to form the International Ice Hockey Association in 1940.[31] Its president W. G. Hardy sought for acceptance by the IOC on terms acceptable to the CAHA.[32][33] CAHA president George Dudley subsequently threatened to withdraw Canada from the Olympics over the definition of amateur. An IOC decision on the matter was postponed when the 1940 Winter Olympics and 1944 Winter Olympics were cancelled due to World War II.[28][34] In 1947, the LIHG agreed to a merger with the International Ice Hockey Association, was subsequently renamed to the IIHF, and recognized the AHAUS as the governing body of hockey in the United States instead of the AAU.[35]

1948–1952

The IIHF considered whether to have an ice hockey tournament at the Winter Olympics, or host a separate Ice Hockey World Championships elsewhere in Switzerland in 1948.[36] Avery Brundage of the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) reportedly campaigned to IIHF delegates to vote against inclusion of the AHAUS in the upcoming Olympics.[37] The LIHG passed a resolution that its teams would only play against teams approved by the CAHA and the AHAUS, which was accepted by the Swiss Olympic organizing committee.[38] Brundage threatened that the USOC would boycott the Olympics if the AHAUS team was recognized.[38] The Swiss Olympic organizing committee insisted on the AHAUS team being recognized, despite persistent charges by Brundage that the AHAUS team was "tainted with professionalism".[39] Brundage and the AAU supported a National Collegiate Athletic Association team instead.[39] After bitter negotiations which were not resolved until the night before the Olympics, the AHAUS team was allowed to play in the tournament, but the IOC declared those games would not count in the standings.[40]

Both Czechoslovakia and Canada won seven games and tied when they played each other. The gold medal winner was determined by goal difference: Canada won the gold because it had an average of 13.8 goals per game compared to Czechoslovakia's average of 4.3.[41] Czechoslovakia's team was quickly improving; it won the 1947 and 1949 World Championships.[42] The AHAUS team finished fourth in the standings in 1948.[43][44]

Discussions began in 1950, whether or not ice hockey would be included in the 1952 Winter Olympics hosted in Oslo. The IOC sought assurance that participating teams would adhere to its amateur code rather than what was accepted by the IIHF, and also wanted to exclude IIHF president Fritz Kraatz from negotiations. George Dudley and W. G. Hardy agreed there would be no negotiations on those terms, nor would they repudiate Kraatz. Dudley referred to the IOC as dictatorial and undemocratic, and expected the IIHF to discuss having its own 1952 Ice Hockey World Championships instead. He further stated that the Olympics would be a financial failure without the inclusion of hockey.[45] Hockey was ultimately included in the Olympics, and the gold medal was won by Canada's team for the second consecutive Games. It would be the last time that a Canadian team would win a gold medal in hockey for 50 years.[46] The United States won silver and Sweden won bronze. A team from Finland competed for the first time.[47]

1956–1976

The Soviet Union competed in its first World Championship in 1954, defeating Canada and winning the gold medal.[48] At the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, the Soviet team went undefeated and won its first gold medal. Canada's team lost to the Soviets and the United States in the medal round, winning the bronze.[48] The 1960 Winter Olympics, in Squaw Valley, United States, saw the first, and to date only, team from Australia compete in the tournament. Canada, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Sweden were the top four teams heading into the Games, but were all defeated by the American team, which won all seven games en route to its first Olympic gold medal. Canada won the silver medal and the Soviet Union won the bronze.[49]

At the 1964 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria, the Soviet team won all seven of its games, earning the gold medal. Canada finished the tournament with five wins and two losses, putting the team in a three-way tie for second place with Sweden and Czechoslovakia. Before 1964, the tie-breaking procedure was based on goal difference in games against teams in the medal round; under that system, Canada would have placed third ahead of the Czechoslovakian team. During the tournament the procedure was changed to take all games into consideration, which meant that the Canadians finished fourth.[50] At the time, the Olympics counted as the World Championships; under their (unchanged) rules, Canada should have received bronze for the World Championships.[51][52][53]

The Soviet Union won its third gold medal with a 7–1 record in the 1968 Grenoble Olympics. Czechoslovakia and Canada won the silver and bronze medals.[54] It was the last time that the Olympics were counted as the World Championships. In 1970, Canada withdrew from international ice hockey competition protesting the use of full-time "amateurs" by the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia,[55][56][57] and the team did not participate in the 1972 and 1976 Winter Olympics.[57] Led by goaltender Vladislav Tretiak and forwards Valeri Kharlamov, Alexander Yakushev, Vladimir Petrov and Boris Mikhailov, the Soviet team won gold at both the 1972 Games in Sapporo, Japan and 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria.[58] In 1971, the United States finished last at the World Championships and was relegated to Pool B. The team qualified for the 1972 Olympics and won silver, making it the first Pool B team to win an Olympic medal.[59] Czechoslovakia won the bronze medal in 1972.[60] In 1976, Czechoslovakia won the silver and West Germany won bronze.[61] Along with Canada, the Swedish team did not participate in the 1976 tournament joining the boycott.[62]

1980: "Miracle on Ice"

The Winter Olympics returned to Lake Placid, New York in 1980. Twelve teams participated in the tournament, including Canada for the first time since 1968. The Soviet Union had won the gold medal in five of the six previous Winter Olympic Games, and were the favorites to win once more in Lake Placid. The team consisted of full-time players with significant experience in international play. By contrast, the United States' team—led by head coach Herb Brooks—consisted exclusively of amateur players with mostly college experience, and was the youngest team in the tournament and in U.S. national team history. In the group stage, both the Soviet and U.S. teams were unbeaten; the U.S. achieved several notable results, including a 2–2 draw against Sweden, and a 7–3 upset victory over second-place favorites Czechoslovakia.

For the first game in the medal round, the United States played the Soviets. The first period finished tied at 2–2, and the Soviets lead 3–2 following the second. The U.S. team scored two more goals to take their first lead during the third and final period, winning the game 4–3. Following the game, the U.S. went on to clinch the gold medal by beating Finland in the final. The Soviet Union took the silver medal by beating Sweden.

The victory became one of the most iconic moments of the Games and in U.S. sports. Equally well-known was the television call of the final seconds of the game by Al Michaels for ABC, in which he declared: "Do you believe in miracles?! YES!" In 1999, Sports Illustrated named the "Miracle on Ice" the top sports moment of the 20th century.[64] As part of its centennial celebration in 2008, the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) named the "Miracle on Ice" as the best international ice hockey story of the past 100 years.[65]

1984–1994

At the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union won its sixth gold medal. Czechoslovakia and Sweden won the silver and bronze medals.[66] The 1988 Winter Olympics were held in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, where the Soviet team captured its seventh and final gold medal. The Soviets' last Olympic game was a loss to Finland. The Finnish team was not considered a serious medal contender—it had competed in the World Championships since 1939 and had not won a single medal. However, Finland upset the Soviets 2–1 and won silver.[67] The IIHF decided to change the tournament format because in several cases, the gold medal winner had been decided before the final day of play. During a congress in 1990, the IIHF introduced a playoff system.[68] The new system was used at the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, France. Preliminary round-robin games were held and followed by an eight-team cup-system style medal round that culminated in a gold medal game.[8]

Before 1989, players who lived in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and other nations behind the Iron Curtain were not allowed to leave and play in the NHL.[70] Soviet officials agreed to allow players to leave following the 1989 World Championships.[71][72] The Soviet Union dissolved in December 1991. Nine former Soviet states became part of the IIHF and started competing internationally, including Belarus, Kazakhstan, Latvia and Ukraine.[73] At the 1992 Olympics, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan competed as one entity, known as the Unified Team.[74] In the final, the Unified Team defeated Canada to win gold while Czechoslovakia won the bronze.[74]

Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in January 1993. The IIHF recognized the Czech Republic as the successor to Czechoslovakia, allowing the team to retain its position in the top World Championship division, while Slovakia started in the lowest division (Pool C) in 1994 and was forced to work its way up.[75] Both nations competed in the tournament at the 1994 Winter Olympics, as did Russia. Slovakia and Finland both finished the preliminary round undefeated. Slovakia lost their medal round quarter-final game to Russia 2–3 OT, who later lost to Sweden 3–4 in the semi-final and Finland (who was defeated by Canada in another semi-final) 0–4 in the bronze medal game. In the gold medal game between Sweden and Canada, both teams finished regulation and overtime play with a 2–2 tie. In the resulting shootout, the first in Olympic competition,[76] both nations scored two goals, which resulted in a sudden death shootout. Peter Forsberg of Sweden scored one of the most famous goals in Olympic history by faking a forehand shot, then sliding a one-handed backhand shot past goaltender Corey Hirsch.[77][78][79] Canada's final shooter Paul Kariya's shot was saved by Tommy Salo and Sweden won the game and its first gold medal.[80]

1998–2014

In 1995, an agreement to allow NHL players to participate in Olympics was reached between the IOC, IIHF, NHL, and National Hockey League Players' Association (NHLPA).[81] The format of the 1998 tournament was adjusted to accommodate the NHL's schedule. Canada, considered a pre-tournament favourite, was upset in the semi-final round by the Czech Republic and then lost the bronze medal game to Finland.[82] Led by goaltender Dominik Hašek, the Czech team defeated Russia, winning its first gold medal in the sport.[9] Following the tournament, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman commented that it "was what we had predicted and hoped for from a pure hockey perspective, [it was] a wonderful tournament".[83]

The next tournament format was hosted in Salt Lake City, United States. Finnish centre Raimo Helminen became the first ice hockey player to compete in six tournaments.[69] In the quarter-finals, Belarus defeated Sweden in one of the biggest upsets since the Miracle on Ice.[84][85] The team lost to Canada 7–1 in the semi-final and Russia 7–2 in the bronze medal game, respectively.[86] The Canadian team rebounded from a disappointing first round and defeated the American team (who eliminated Russia 3–2 in the semi-final) in the gold medal game, winning their first gold medal in 50 years and seventh in men's hockey overall.[87]

The tournament format was adjusted for 2006. In the semi-finals, Sweden defeated the Czech Republic 7–3, and Finland ousted Russia 4–0. Sweden won the gold medal over Finland 3–2 and the Czech Republic won the bronze medal over Russia 3–0. Three months later, Sweden won the 2006 World Championships and became the first team to win the Olympic and World Championship gold in the same year.[88] Allegations have surfaced of Sweden throwing a game against Slovakia so the Swedes would face Switzerland in the quarterfinals instead of Canada or the Czech Republic. Shortly before the game, Sweden coach Bengt-Åke Gustafsson was reported to have publicly contemplated tanking in order to avoid those teams, saying about Canada and the Czechs, "One is cholera, the other the plague."[89]

The 2010 Winter Olympics were held in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, the first time since NHL players started competing that the Olympics were held in a city with an NHL team. Teemu Selänne of Finland scored his 37th point, breaking the record of 36 first set by Canadian Harry Watson in 1924 and later tied by Vlastimil Bubník of Czechoslovakia, and Valeri Kharlamov of the Soviet Union.[22] Slovakia made the final four for the first time, but lost the bronze medal game to Finland 3–5.[90] In the gold medal game, Canada and the United States ended regulation play with a 2–2 tie, making it only the second Olympic gold medal match to go into overtime. Canadian player Sidney Crosby scored the winning goal 7:40 into overtime play to give Canada its eighth gold medal in men's hockey.[91]

The 2014 Winter Olympics were held in Sochi, Russia, and retained the same game format used in Vancouver 2010, while returning to the larger international-sized ice rinks.[92] Slovenia participated for the first time, upsetting Slovakia in the round-robin before losing to Sweden in the quarterfinals 0–5, for its best finish in any international tournament.[93] Latvia upset Switzerland 3–1 in the qualification playoffs, also making it to the Olympic quarterfinals for the first time, where they were narrowly defeated by Canada 2–1.[94] Host nation Russia, considered a pre-tournament favourite, lost 3–1 in the quarterfinals to Finland and finished fifth.[95] Entering the semi-finals undefeated after outscoring opponents 20–6, the United States lost to Canada 0–1, then lost the bronze medal game against Finland 0–5. Teemu Selänne scored six more points in the tournament, was named tournament MVP and boosted his modern-era Olympic career record for points to 43 (24 goals, 19 assists). At the age of 43, he also set records as both the oldest Olympic goal-scorer and oldest Olympic ice hockey medal winner.[96] Canada defeated Sweden 3–0 to win its ninth Olympic gold medal. The team did not trail at any point over the course of the tournament, and became the first back-to-back gold medal winner since the start of NHL participation in 1998, as well as the first team to go undefeated since 1984.[97]

2018–2022

The Olympic ice hockey tournament in PyeongChang in 2018 was held without participation of NHL players, for the first time since the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer.[98] The favorites to win the gold medal were the Russians due to their domestic league, the KHL, taking an Olympic break and allowing such stars as Pavel Datsyuk and Ilya Kovalchuk to play on the team.[99][100] As a consequence of a doping scandal, the IOC banned the Russian federation, but allowed Russian athletes to compete under the Olympic flag after passing anti-doping tests.[101] The final was played between the Germans, who unexpectedly eliminated the Canadians in the semi-final,[102] and the Olympic Athletes from Russia. In the final, the Russians prevailed, defeating Germany 4–3, and won the gold medal after Kirill Kaprizov scored the winning goal in overtime. The Russian players sang the banned anthem during the medal ceremony, but the IOC decided not to pursue any action.[103] Canada won the bronze medal over the Czech Republic 6–4.[104]

Although NHL players were originally planned to participate in the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, the league and the NHL Players' Association announced on 21 December 2021, that they would be pulling out of the tournament, citing the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[105][106][107] Finland won their first ever ice hockey gold medal after going undefeated and beating the Russian Olympic Committee in the final. Slovakia claimed their first ever bronze medal after defeating Sweden 4–0.[108] For the first time in history, the Czech Republic did not qualify for the quarter-finals and finished in ninth place, their lowest placement in history.[109]

Women's tournament

Addition to the programme

At the 99th IOC Session in July 1992, the IOC voted to approve women's hockey as an Olympic event beginning with the 1998 Winter Olympics as part of their effort to increase the number of female athletes at the Olympics.[112] Women's ice hockey had not been in the programme when Nagano, Japan had won the right to host the Olympics in June 1991, and the decision required approval by the Nagano Winter Olympic Organizing Committee (NAOOC). The NAOOC was initially hesitant to include the event because of the additional costs of staging the tournament and because they felt their team, which had failed to qualify for that year's World Championships, could not be competitive.[113] According to Glynis Peters, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association's (CAHA) head of female hockey, "the Japanese would have to finance an entirely new sports operation to bring their team up to Olympic standards in six years, which they were also really reluctant to do."[114] In November 1992, the NWOOC and IOC Coordination Committee reached an agreement to include a women's ice hockey tournament in the programme.[113] Part of the agreement was that the tournament would be limited to six teams, and no additional facilities would be built. The CAHA also agreed to help build and train the Japanese team so that it could be more competitive.[114] The IOC had agreed that if the NAOOC had not approved the event, it would be held at the 2002 Winter Olympics.[113] The format of the first tournament was similar to the men's: preliminary round-robin games followed by a medal round playoff.[115]

1998–2006

Before 1998, women's hockey had been dominated by Canada. Canadian teams had won every World Championship up to that point; however, by 1997, the American team had improved and was evenly matched with Canada. In thirteen games played between the two teams in 1997, Canada won seven and the United States won six. The 1998 Olympic tournament also included teams from Finland, Sweden, China and host Japan. Canada and the United States dominated the round-robin portion. In their head-to-head match, the United States overcame a 4–1 deficit to win 7–4.[116] The two teams met in the final, which the United States won 3–1 to become the third American ice hockey team to win Olympic gold. Finland defeated China 4–1 to win the bronze medal.[117]

For the 2002 Winter Olympics, the number of teams was increased to eight with Russia, Germany and Kazakhstan qualifying for the first time.[118] The Canadian and American teams went undefeated in the first round and semi-finals, setting up a gold medal rematch that the Canadian team won 3–2.[119] Following the game, members of the Canadian team accused the Americans of stomping on a Canadian flag in their dressing room, although an investigation later proved the rumour false.[120] The Swedish team won the bronze medal over Finland 2–1, the nation's first in women's ice hockey.[121]

In 2006, Sweden defeated the US in a shootout in the semi-finals, marking the first time the US had lost to an opponent other than Canada.[122] The upset drew comparisons to the Miracle on Ice from 1980.[123] In the medal games, Canada defeated Sweden 4–1 to claim its second consecutive gold medal, while the Americans beat Finland 4–0 to win the bronze.[124][125][126]

2010 and debate on removal from the Olympics

In 2010, eight teams participated, including Slovakia for the first time.[127] In the gold medal game, Canada defeated the United States 2–0 to win their third consecutive gold. The Finnish team won the bronze medal over Sweden 3–2 OT, their first since 1998.[128]

The future of international women's ice hockey was discussed at the World Hockey Summit in 2010, and dealt with how IIHF member associations could work together to grow the game and increase registration numbers, and the relative strength of the women's game in North America compared to the rest of the world.[129] International Olympic Committee president Jacques Rogge raised concerns that the women's hockey tournament might be eliminated from the Olympics since the event was not competitively balanced and was dominated by Canada and the United States.[130] Team Canada captain Hayley Wickenheiser explained that the talent gap between the North American and European countries was due to the presence of women's professional leagues in North America, along with year-round training facilities. She stated the European players were talented, but their respective national team programs were not given the same level of support as the European men's national teams, or the North American women's national teams.[131] She stressed the need for women to have their own professional league which would be for the benefit of international hockey. IIHF vice-president Murray Costello promised to invest $2-million towards developing international women's hockey.[132]

2014–2022

At the 2014 Winter Olympics, Canada defeated the United States 3–2, as Marie-Philip Poulin scored at 8:10 of overtime to win their fourth consecutive gold, rebounding from a two-nothing deficit late in the game. With the win, Canadians Hayley Wickenheiser, Jayna Hefford and Caroline Ouellette became the first athletes to win four ice hockey gold medals. They also joined Soviet biathlete Alexander Tikhonov and German speedskater Claudia Pechstein as the only athletes to win gold medals in four straight Winter Olympics.[133] In the bronze medal game Switzerland beat Sweden 4–3 to win their first women's medal.[134]

In 2018, the United States defeated Canada for the gold medal in a shootout, winning 3–2. The Americans' winning the gold medal game marks the first time in 20 years that the United States took home a gold medal in women's hockey. They previously won in 1998 in Nagano, Japan, which was also against Canada.[135] Canada's loss effectively ended their winning streak of four consecutive winter games, having won since 2002.[136]

The 2022 edition was played with ten teams for the first time.[137] Canada won their fifth gold medal, defeating the United States in the final 3–2.[138] Finland defeated Switzerland 4–0 for the bronze medal.[139] The final standings were a repeat of the 2021 IIHF Women's World Championship.[140]

Rules

Qualification

Since 1976, 12 teams have participated in the men's tournament, except in 1998 and 2002, when the number was raised to 14. The number of teams has ranged from 4 (in 1932) to 16 (in 1964). After the NHL allowed its players to compete at the 1998 Winter Olympics, the "Big Six" teams (Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Russia, Sweden and the United States) were given automatic qualification and byes to the final round.[141] The number of teams was increased to 14 so that a preliminary round-robin tournament consisting of eight teams could be held. The top two teams from the preliminary round (Belarus and Kazakhstan) joined the "Big Six" in the finals. A similar system was used in 2002.[142] For the following tournament, the number of teams was lowered to 12 so that all teams played fewer games.[143] Qualification for the men's tournament at the 2010 Winter Olympics was structured around the 2008 IIHF World Ranking. Twelve spots were made available for teams. The top nine teams in the World Ranking after the 2008 Men's World Ice Hockey Championships received automatic berths. Teams ranked 19th through 30th played in a first qualification round in November 2008. The top three teams from the round advanced to the second qualification round, joined by teams ranked 10th through 18th. The top three teams from this round advanced to the Olympic tournament.[144][145]

The women's tournament uses a similar qualification format. The top six teams in the IIHF Women's World Ranking after the 2008 Women's World Ice Hockey Championships received automatic berths. Teams ranked 13th and below were divided into two groups for a first qualification round in September 2008. The two group winners advanced to the second qualification round, where the teams ranked seventh through twelfth joined them.[146]

Players

Eligibility

The IIHF lists the following requirements for a player to be eligible to play in international tournaments:[147]

- "Each player must be under the jurisdiction of an IIHF member national association."

- "Each player must be a citizen of the country he/she represents."

If a player who has never played in an IIHF competition changes their citizenship, they must participate in national competitions in their new country for at least two consecutive years and have an international transfer card (ITC).[147] If a player who has previously played in an IIHF tournament wishes to change their national team, they must have played in their new country for four years. A player can only do this once.[147] The original IOC rules stated that an athlete that had already played for one nation could not later change nations under any circumstances.[7]

Use of professional players

Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the IOC, was influenced by the ethos of the aristocracy as exemplified in the English public schools.[148] The public schools subscribed to the belief that sport formed an important part of education and there was a prevailing concept of fairness in which practicing or training was considered cheating.[148] As class structure evolved through the 20th century, the definition of the amateur athlete as an aristocratic gentleman became outdated.[148] The advent of the state-sponsored "full-time amateur athlete" of the Eastern Bloc countries further eroded the ideology of the pure amateur, as it put the self-financed amateurs of the Western countries at a disadvantage. The Soviet Union entered teams of athletes who were all nominally students, soldiers, or working in a profession, but many of whom were in reality paid by the state to train on a full-time basis.[1] Nevertheless, the IOC held to the traditional rules regarding amateurism until 1988.[2]

Near the end of the 1960s, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) felt their amateur players could no longer be competitive against the Soviet team's full-time athletes and the other constantly improving European teams. They pushed for the ability to use players from professional leagues but met opposition from the IIHF and IOC. At the IIHF Congress in 1969, the IIHF decided to allow Canada to use nine non-NHL professional hockey players[57] at the 1970 World Championships in Montreal and Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.[149] The decision was reversed in January 1970 after IOC President Brundage said that ice hockey's status as an Olympic sport would be in jeopardy if the change was made.[57] In response, Canada withdrew from international ice hockey competition and officials stated that they would not return until "open competition" was instituted.[57][150] Günther Sabetzki became president of the IIHF in 1975 and helped to resolve the dispute with the CAHA. In 1976, the IIHF agreed to allow "open competition" between all players in the World Championships. However, NHL players were still not allowed to play in the Olympics, because of the unwillingness of the NHL to take a break mid-season and the IOC's amateur-only policy.[151]

Before the 1984 Winter Olympics, a dispute formed over what made a player a professional. The IOC had adopted a rule that made any player who had signed an NHL contract but played less than ten games in the league eligible. However, the United States Olympic Committee maintained that any player contracted with an NHL team was a professional and therefore not eligible to play. The IOC held an emergency meeting that ruled NHL-contracted players were eligible, as long as they had not played in any NHL games.[152] This made five players on Olympic rosters—one Austrian, two Italians and two Canadians—ineligible. Players who had played in other professional leagues—such as the World Hockey Association—were allowed to play.[152] Canadian hockey official Alan Eagleson stated that the rule was only applied to the NHL and that professionally contracted players in European leagues were still considered amateurs.[153] Murray Costello of the CAHA suggested that a Canadian withdrawal was possible.[154] In 1986, the IOC voted to allow all athletes to compete in the Olympic Games starting in 1988.[155][156]

NHL participation

The NHL decided not to allow all players to participate in 1988, 1992, 1994, 2018, and 2022 because the Winter Olympics typically occur in February, during the league's regular season. To allow participation, the NHL would have been forced to take a break in its schedule.[157]

In 1992, National Basketball Association (NBA) players participated in the 1992 Summer Olympics. NHL commissioner Gary Bettman (an NBA executive in 1992) commented that the "[NBA]'s worldwide awareness grew dramatically". He hoped that NHL participation would "get exposure like the world has never seen for hockey".[81] The typical NBA season is held in the winter and spring, so the Summer Olympics do not conflict with the regular season schedule. Bettman "floated a concept of moving hockey to the Summer Games", but this was rejected because of the Olympic Charter.[81] In March 1995, Bettman, René Fasel, IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch and NHLPA executive director Bob Goodenow met in Geneva, Switzerland. They reached an agreement that allowed NHL players to participate in the Olympics, starting with the 1998 Games in Nagano, Japan.[81] The deal was officially announced by the NHL on 2 October 1995. Bettman said: "We're doing this to build the game of hockey, pure and simple, we think whatever benefits are recouped, it will end up making this game bigger, stronger and healthier."[158][159]

The 2004–05 NHL season was locked out and eventually cancelled because of a labour dispute between the league and its players. In January 2005, Bettman commented that he was hesitant to allow league participation in the Olympics because he did not like the idea of stopping play mid-season after the cancellation of the previous season.[160] The lockout was resolved in July 2005 and the newly negotiated NHL Collective Bargaining Agreement allowed league participation in the 2006 and 2010 Winter Olympics.[161] Some NHL team owners were against their players participating in the tournament because of concerns about injury or exhaustion. Philadelphia Flyers owner Ed Snider commented that "I'm a believer in the Olympics and I think it's good for the NHL to participate, having said that, the people who participate should be the ones who are absolutely healthy."[162] Some NHL players used the break as an opportunity to rest and did not participate in the tournament,[163] and several players were injured during the Olympics and were forced to miss NHL games. Bettman said that several format changes were being discussed so that the tournament would be "a little easier for everybody".[164]

It was originally thought that for NHL participating in the 2014 Winter Olympics a deal would have to be negotiated between the NHL and NHLPA in the Collective Bargaining Agreement.[166] In January 2013, the NHL and NHLPA agreed on a new Collective Bargaining Agreement.[167] However, the decision on NHL participation at the Olympics was later announced on 19 July 2013. As part of the deal, the NHL will go on break for 17 days during the Olympics and will send 13 on-ice officials to help with the Games.[168] NHL management was hesitant to commit to the tournament; Bettman argued the Olympic break is a "strain on the players, on the schedule and on fans", adding that "the benefits we get tend to be greater when the Olympics are in North America than when they're in distant time zones."[169] According to Bettman, most of the NHL team owners agree with his position, and feel that the league does not receive enough benefits to justify the schedule break and risk of player injuries.[170] René Fasel wants NHL participation and vowed that he would "work day and night to have NHL players in Sochi".[171]

At an October 2008 press conference, then-NHLPA executive director Paul Kelly stated that the players want to return to the Olympics and would try to include the ability in the next agreement.[170] Russian NHL players Alexander Ovechkin and Evgeni Malkin stated that they want to participate in the tournament and would do so without the permission of the NHL, if necessary.[165] Paul Kelly also believed that the NHL's strained relationship with the Ice Hockey Federation of Russia and the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) could affect participation.[166] In a 2009 interview, KHL president Alexander Medvedev claimed that the unwillingness of NHL officials to immediately commit to the Sochi Games was "an instrument of pressure" to force a transfer agreement between the two leagues.[172]

A major sticking point over NHL participation has been the insurance of players; for the 2014 Winter Olympics, the IOC paid around US$7 million to insure NHL players participating in the Games. In April 2016, the IOC announced that beginning in 2018, it would no longer cover accommodations, insurance, or travel for NHL players in the Olympics, prompting the IIHF to ask for support from national ice hockey associations and National Olympic Committees to help cover costs; Matti Nurminen of the Finnish Ice Hockey Association argued that it was the responsibility of the event's organizer to cover costs, and that "In our opinion, the same party should pay the bills, and that's not us. All the countries replied to the IIHF that they are not willing to pay for the insurance or the travel or any of the other expenses that are related to having the NHL players participate in Pyeongchang." The New York Times felt that the removal of this financial support would put NHL participation at Pyeongchang in jeopardy, noting the already-strenuous relationship between the NHL and the IOC; Gary Bettman noted that the NHL does not profit from their presence, adding that "in fact, we kind of disappear for two weeks because historically the IOC hasn't even let us join in promoting our participation in the Olympics."[173]

On 3 April 2017, the NHL announced that it would not participate in the 2018 Winter Olympics. In that statement, the NHL said that it had been open to hearing from the IOC, the IIHF, and the players' association on ways to make Olympic participation more attractive to team owners, but no meaningful dialogue on that matter had materialized. As to reasons the Board of Governors might be interested in re-evaluating their strongly held views on the subject, the NHLPA "confirmed that it has no interest or intention of engaging in any discussion that might make Olympic participation more attractive to the Clubs", and that it would not schedule a break for the Olympics in the 2017–18 season.[174]

Although in the following months the president of the IIHF René Fasel tried to convince NHL to change its decision,[175] in September he stated that there was no chance for participation of NHL players in the Pyeongchang olympic tournament. "I can say that this is now gone. We can tick that off the list. We will have to look ahead to China and the Beijing 2022 winter Games because there is an interest of the league and we have noted that. But logistically it is practically impossible for Pyeongchang. That train has left the station", he said.[98] Some NHL players expressed their discontent with league's decision to skip the Olympics.[176] Alexander Ovechkin, captain of the Washington Capitals: "The Olympics are in my blood and everybody knows how much I love my country",[177] adding that "he would compete with Russia if he were the only NHL player to travel to South Korea".[98] "It's brutal, [...] I don't think there's any reason we shouldn't be going", said Justin Faulk, 2014 Olympian and alternate captain for the Carolina Hurricanes.[178] Eventually, the NHL players were forced to follow the league's decision and stay in their clubs during the 2018 Olympics.[179]

Game rules

At the first tournament in 1920, there were many differences from the modern game: games were played outdoors on natural ice, forward passes were not allowed,[15] the rink (which had been intended to be used only for figure skating) was 56 m × 18 m (165 ft × 58.5 ft)[7] and two 20-minute periods were played.[14] Each team had seven players on the ice, the extra position being the rover.[8] Following the tournament, the IIHF held a congress and decided to adopt the Canadian rules—six men per side and three periods of play.[15]

The tournaments follow the rules used by the IIHF. At the 1969 IIHF Congress, officials voted to allow body-checking in all three zones in a rink similar to the NHL; it's prohibited for women. Before that, body-checking was only allowed in the defending zone in international hockey[180] Several other rule changes were implemented in the early 1970s: players were required to wear helmets starting in 1970, and goaltender masks became mandatory in 1972.[8] In 1992, the IIHF switched to using a playoff system to determine medalists and decided that tie games in the medal round would be decided in a shootout.[181] In 1998, the IIHF passed a rule that allowed two-line passes. Before then, the neutral zone trap had slowed the game down and reduced scoring.[182]

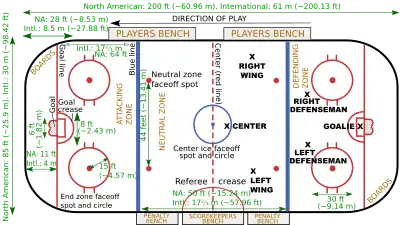

The current IIHF rules differ slightly from the rules used in the NHL.[183] One difference between NHL and IIHF rules is standard rink dimensions: the NHL rink is narrower, measuring 61 m × 26 m (200 ft × 85 ft), instead of the international size of 61 m × 30.5 m (200 ft × 100 ft)[184] The larger international size allows for a faster and less physical style of play.[185][186] Another rule difference between the NHL and the IIHF rules concerns how icing is called. In the NHL, a linesman stops play due to icing if a defending player (other than the goaltender) is not behind an attacking player in the race to the end-zone faceoff dots in his defensive zone,[187] in contrast to the IIHF rules in which play is stopped the moment the puck crosses the goal line.[187] The NHL and IIHF also differ in penalty rules. The NHL calls five-minute major penalties for more dangerous infractions of the rules, such as fighting, in addition to the minor and double minor penalties called in IIHF games.[188] This is in contrast to the IIHF rule, by which players who fight risk a game misconduct & major penalties.[189] Beginning with the 2005–06 season, the NHL instituted several new rules. Some were already used by the IIHF, such as the shootout and the two-line pass.[190] Others were not picked up by the IIHF, such as those requiring smaller goaltender equipment and the addition of the goaltender trapezoid to the rink.[191] However, the IIHF did agree to follow the NHL's zero-tolerance policy on obstruction and required referees to call more hooking, holding, and interference penalties.[192][193]

Each team is allowed to have between 15 and 20 skaters (forwards and defencemen) and two or three goaltenders, all of whom must be citizens of the nation they play for.[194][195]

Banned substances

The IIHF follows the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) regulations on performance-enhancing drugs. The IIHF maintains a Registered Testing Pool, a list of top players who are subjected to random in-competition and out-of-competition drug tests.[196] According to the WADA, a positive in-competition test results in disqualification of the player and a suspension that varies based on the number of offences. When a player tests positive, the rest of their team is subjected to testing; another positive test can result in a disqualification of the entire team.[197][198][199][200]

| Athlete | Nation | Olympics | Substance | Punishment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alois Schloder | 1972 | Ephedrine | Six month suspension from IIHF | The first Winter Olympics athlete to test positive for a banned substance,[201] Schloder was banned from the rest of the Games but his team was allowed to continue playing.[60] After his innocence was proven, his disqualifications was lifted, and he was allowed to take part in the 1972 Ice Hockey World Championships. | |

| František Pospíšil | 1976 | Codeine | None | Team doctor Otto Trefny, who prescribed Pospíšil the drug as treatment for the flu, received a lifetime ban. The team was forced to forfeit a game against Poland but went on to win the silver medal, which Pospíšil also received.[202][203] | |

| Jarosław Morawiecki | 1988 | Testosterone | 18-month suspension from IIHF | The Polish team was allowed to continue playing without Morawiecki, but were stripped of two points they earned in a victory over France.[204] | |

| Mattias Öhlund | 2002 | Acetazolamide | None | Öhlund had inadvertently ingested the substance in medication he was taking after undergoing eye surgery and was not suspended.[205] | |

| Vasily Pankov | 2002 | 19-Norandrosterone | Retroactively disqualified | Pankov was also forced to return his Olympic diploma. Evgeni Lositski, the team doctor, was banned from the following two Olympics.[206] | |

| Ľubomír Višňovský | 2010 | Pseudoephedrine | Issued a reprimand | Višňovský took Advil Cold & Sinus to combat a cold, unaware that it contained a WADA prohibited substance. He had consulted with the Slovak national team doctor and declared that he was taking the medication. Levels on samples two and three were well below WADA limits.[207] | |

| Vitalijs Pavlovs | 2014 | Methylhexaneamine (dimethylpentylamine) | Disqualified from quarter-final game | Pavlovs was disqualified from the Canada–Latvia quarter-final game and was forced to return his Olympic diploma. According to Pavlovs, he had "been taking food supplements upon the recommendation of the doctor of his club team and that he did not understand how this substance entered his body".[208] | |

| Ralfs Freibergs | 2014 | Anabolic androgenic steroid | Disqualified from quarter-final game | Freibergs was disqualified from the Canada–Latvia quarter-final game and was forced to return his Olympic diploma. | |

| Nicklas Bäckström | 2014 | Pseudoephedrine | Pulled from gold medal game | Bäckström was taking an over-the-counter medication to treat a sinus condition. He consulted with the team doctor and was informed that there would not be a problem. Bäckström's medal was initially withheld but was returned the following month. The IOC determined that "there was no indication of any intent of the athlete to improve his performance by taking a prohibited substance".[209][210][211] | |

| Inna Dyubanok | 2014 | Disappearing sample | Retroactively disqualified | IOC sanctions imposed in 2017.[212] | |

| Yekaterina Lebedeva | |||||

| Yekaterina Pashkevich | |||||

| Anna Shibanova | |||||

| Yekaterina Smolentseva | |||||

| Galina Skiba | |||||

| Tatiana Burina | |||||

| Anna Shukina |

In late 2005, two NHL players who had been listed as potential Olympians failed drug tests administered by the WADA. Bryan Berard tested positive for 19-Norandrosterone.[213] José Théodore failed a drug test because he was taking Propecia, a hair loss medication that contains the non-performance-enhancing drug Finasteride.[214] Both players received two-year bans from international competition, although neither had made their team's final roster.[215] On 6 December 2017 six Russian women ice hockey players were disqualified for doping violations. Results of the Russian women's team at the 2014 Winter Olympics were made void.[216] Two other Russian players, Tatiana Burina and Anna Shukina, were also disqualified ten days later.[217]

Results

Men

Summary

Medal table

Accurate as of 2022 Winter Olympics.[218]

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 16 | |

| 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| 3 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 11 | |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (16 entries) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | |

Alternate medal table

Unlike the IOC, the IIHF combines the records of predecessor and successor nations.[219]

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 16 | |

| 2 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 14 | |

| 3 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 11 | |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | |

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals (10 entries) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | |

Participating nations

Key

| # | The final rank of the team. If multiple numbers are listed the IOC and IIHF differ in their results. |

| =# | Indicates that two or more teams shared the same final rank. |

| #,# | Indicates IOC final rank, then IIHF final rank. |

| nr | Indicates team participated, but no IOC final rank. |

| dq | The team was disqualified by the IOC. |

| ( ) | Temporary IOC name different from IIHF member name. |

| – | The team did not participate that year. |

| Q | The team has qualified for the tournament. |

| #(#) | Indicates IOC total, then IIHF total. |

| #* | Indicates total for team using a temporary IOC name. |

| The nation did not exist with that designation at that time. | |

| References:[220][221][222][223] | |

| Nation | 1920 |

1924 |

1928 |

1932 |

1936 |

1948 |

1952 |

1956 |

1960 |

1964 |

1968 |

1972 |

1976 |

1980 |

1984 |

1988 |

1992 |

1994 |

1998 |

2002 |

2006 |

2010 |

2014 |

2018 |

2022 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | =5 | – | =7 | 7,8 | – | 10 | – | 13 | 13 | – | 8 | – | =9,10 | 9 | – | 12 | 14 | 12 | – | – | 10 | – | – | 13 | |

| – | =5,7 | 4 | – | 9 | – | – | – | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 7 | =8 | – | =13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | – | – | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 23 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | =5 | =5 | – | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 16 | |||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 1 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | – | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 18 | |

| 2==5,6 | =5 | =5 | – | =9 | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | – | – | – | – | 11 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 14 | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | |

| – | – | =8 | 3 | =5 | – | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 11 | – | 2 | 10 | 12 (11) | ||||||||||

| (GER) | (EUA) | (EUA) | (EUA) | 7 | 7 | 3 | =9,10 | 5 | 5 | 6(10) | ||||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 6 | 7 | 3* | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| – | 3 | 4 | – | 1 | 5,6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | |

| – | – | 11 | – | =7 | – | – | – | – | 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | |

| – | – | – | – | =9 | 8,9 | – | 7 | – | 15 | – | – | – | – | =9,9 | – | 12 | 9 | 12 | – | 11 | – | – | – | – | 9 | |

| – | – | – | – | =9 | – | – | – | 8 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 9 | =11,12 | – | – | – | – | 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | |

| – | 8 | – | 9 | – | – | – | – | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | =13 | – | – | – | 9 | 12 | 12 | 8 | – | 11 | 6 | ||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | =9,9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 9 | – | – | 10 | 11 | 8 | – | =11,11 | =11,12 | 12 | 9 | 11 | – | – | – | 10 | 12 | 8 | – | 12 | |

| 1 | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| – | – | =8 | 4 | =9 | 6,7 | 6 | 8 | – | 9 | – | 6 | 6 | =7,7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | |

| 2 | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 12 | – | 7 | =7,8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | |

| (EUN) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | (OAR) | (ROC) | 6(9) | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 9 | – | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | – | 1 | ||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 2 | – | =5 | 4,5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | – | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 23 | |

| 2==5,5 | =7 | 3 | – | =13 | 3 | 5 | 9 | – | 8 | – | 10 | 11 | – | – | 8 | 10 | – | – | 11 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 18 | |

| – | – | 10 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | – | 2 | 3 | dq,4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 24 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 9 | 11 | 10 | – | =11,11 | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | ||||||

| Total | 7 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 16 | 14 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

Women

Summary

| # | Year | Hosts | Gold medal game | Bronze medal game | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Score | Silver | Bronze | Score | Fourth place | |||

| 1 | 1998 Details |

Nagano |

United States |

3–1 | Canada |

Finland |

4–1 | China |

| 2 | 2002 Details |

Salt Lake City |

Canada |

3–2 | United States |

Sweden |

2–1 | Finland |

| 3 | 2006 Details |

Torino |

Canada |

4–1 | Sweden |

United States |

4–0 | Finland |

| 4 | 2010 Details |

Vancouver |

Canada |

2–0 | United States |

Finland |

3–2 OT | Sweden |

| 5 | 2014 Details |

Sochi |

Canada |

3–2 OT | United States |

Switzerland |

4–3 | Sweden |

| 6 | 2018 Details |

Pyeongchang |

United States |

3–2 SO | Canada |

Finland |

3–2 | Olympic Athletes from Russia |

| 7 | 2022 Details |

Beijing |

Canada |

3–2 | United States |

Finland |

4–0 | Switzerland |

Medal table

Accurate as of 2022 Winter Olympics.[218]

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals (5 entries) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 21 | |

Participating nations

Key

| # | The final rank of the team. If multiple numbers are listed the IOC and IIHF differ in their results. |

| =# | Indicates that two or more teams shared the same final rank. |

| #,# | Indicates IOC final rank, then IIHF final rank. |

| nr | Indicates team participated, but no IOC final rank. |

| dq | The team was disqualified by the IOC. |

| ( ) | Temporary IOC name different from IIHF member name. |

| – | The team did not participate that year. |

| Q | The team has qualified for the tournament. |

| #(#) | Indicates IOC total, then IIHF total. |

| #* | Indicates total for team using a temporary IOC name. |

| The nation did not exist with that designation at that time. | |

| References:[224][221][222][223] | |

| Nation | 1998 |

2002 |

2006 |

2010 |

2014 |

2018 |

2022 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |

| 4 | 7 | – | 7 | – | – | 9 | 4 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 1 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 1 | |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 7 | |

| – | 6 | 5 | – | 6,7 | – | – | 3 | |

| – | – | 8 | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 6 | – | – | – | 7,8 | 6 | 6 | 4 | |

| – | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 8 | – | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | 1* | |||||||

| 5 | 1* | |||||||

| – | 5 | 6 | 6 | dq,6 | (OAR) | (ROC) | 4(6) | |

| – | – | – | 8 | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| – | – | 7 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |

| Total | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

Overall medal table

Sources (after the 2022 Winter Olympics):[218]

Accurate as of 2022 Winter Olympics.

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 23 | |

| 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| 3 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 18 | |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 | |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 11 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (16 entries) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 96 | |

Alternate overall medal table

Unlike the IOC, the IIHF combines the records of predecessor and successor nations.[219][225]

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 23 | |

| 2 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 14 | |

| 3 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 18 | |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 | |

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 11 | |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Totals (10 entries) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 96 | |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Benjamin, Daniel (27 July 1992). "Traditions Pro Vs. Amateur". Time. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- 1 2 Schantz, Otto. "The Olympic Ideal and the Winter Games Attitudes Towards the Olympic Winter Games in Olympic Discourses—from Coubertin to Samaranch" (PDF). Comité International Pierre De Coubertin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ↑ "Ice hockey". International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Farrell, Arthur (1899). Hockey: Canada's Royal Winter Game. C.R. Corneil. p. 27.

- ↑ "It all started in Paris, 1908". International Ice Hockey Federation. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Morales 2004, p. 275

- 1 2 3 4 Podnieks 1997, pp. 1–10

- 1 2 3 4 "International hockey timeline". International Ice Hockey Federation. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- 1 2 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #10–Czech Republic wins first "open" Olympics Archived 13 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Chamonix 1924". International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ↑ "Olympic Charter" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 7 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ "This Day in History 1924: First Winter Olympics". This day in History. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ↑ "Sport: Winter Olympics 98–History of the winter Olympics". BBC News. 5 February 1998. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- 1 2 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #21–Ice Hockey debuts at the Olympics Archived 24 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hansen, Kenth (May 1996). "The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey – Antwerp 1920" (PDF). Citius, Altius, Fortius. International Society of Olympic Historians. 4 (2): 5–27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ↑ "IIHF Honour Roll: W. A. Hewitt". Legends of Hockey. Hockey Hall of Fame. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "1920 – Summer Olympics VII (Antwerp, Belgium)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "United States is second at hockey; Victory Over Czechoslovak Team by 16 to 0 Gives Americans 3 Points in Olympics". The New York Times. 29 April 1920. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "1924 – Winter Olympics I (Chamonix, France)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #53–Harry Watson scores at will in Olympics Archived 23 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ice Hockey at the 1924 Chamonix Winter Games: Men's Ice Hockey". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Selanne's 37th point tops Games mark". ESPN. 20 February 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ↑ "1928 – Winter Olympics II (St. Moritz, Switzerland)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Comité Olympique Suisse (1928). Rapport Général du Comité Exécutif des IImes Jeux Olympiques d'hiver (PDF) (in French). Lausanne: Imprimerie du Léman. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ↑ "1932 – Winter Olympics III (Lake Placid, United States)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Lattimer, George, ed. (1932). Official Report III Olympic Winter Games Lake Placid 1932 (PDF). Lake Placid, New York: Olympic Winter Games Committee. pp. 70–72, 270. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #15–Great Britain wins Olympic gold Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Young, Scott (1989). 100 Years of Dropping the Puck. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart Inc. pp. 189–192. ISBN 0-7710-9093-5.

- ↑ "Eastern U.S. Puck Loops Quits A.A.U." Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 31 August 1937. p. 36. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Lockhart, Thomas – Honoured Builder". Legends of Hockey. Hockey Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ↑ Clarke, Robert (16 April 1940). "New Controlling Body Formed at C.A.H.A. Meet". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. p. 15. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Dr. Hardy Outlines Scheme at Annual Gathering C.A.H.A." Lethbridge Herald. Lethbridge, Alberta. 4 January 1941. p. 18. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Rules, Playdowns Discussed at C.A.H.A. Meeting". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 4 January 1941. p. 21. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Diem, Carl, ed. (January 1940). "The Fifth Olympic Winter Games Will Not Be Held" (PDF). Olympic Review (PDF). Berlin: International Olympic Institute (8): 8–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ "C.A.H.A. Gains Few Points at Prague Hockey Confab". Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 22 March 1947. p. 33. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Olympic Hockey Question Soon Will Be Decided". Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 5 July 1947. p. 15. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Hockey Politics Are Rampant in Zurich". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 10 September 1947. p. 18. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Yank Puck Bodies Are Feudin' And Fightin'". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 8 November 1947. p. 22. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Bitter, Long-Drawn Out Olympic Hockey Controversy Still Rages". Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 27 January 1948. p. 12. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Sullivan, Jack (23 February 1960). "'Squawk' Valley Hassles 'Duck Soup'". Brandon Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Comité Olympique Suisse (January 1951). Rapport Général sur les Ves Jeux Olympiques d'hiver St-Moritz 1948 (PDF) (in French). Lausanne: H. Jaunin. p. 69. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ "Past medalists–IIHF World Championships". International Ice Hockey Federation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "Ice Hockey at the 1948 Sankt Moritz Winter Games: Men's Ice Hockey". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks 1997, pp. 53–66

- ↑ "International Puck Bodies Widely Split". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 18 May 1950. p. 17. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "1952 – Winter Olympics VI (Oslo, Norway)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "Finland Ice Hockey: Men's Ice Hockey". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- 1 2 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #25–Soviet Union win their first Olympics, starting a new hockey era Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #16–USA's original but unheralded "Miracle on Ice" Archived 30 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "1964 – Winter Olympics IX (Innsbruck, Austria)". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "'64 Team Canada gets bronze medals". The Sports Network. 30 April 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "1964 Canadian Olympic hockey team to be honoured". CBC Sports. 29 April 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "IIHF denies Canada 1964 bronze". The Sports Network. 5 June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Xth Winter Olympic Games Official Report (PDF). Comité d'Organisation des xèmes Jeux Olympiques d'Hiver de Grenoble. 1969. p. 386. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ IIHF (2008). "PROTESTING AMATEUR RULES, CANADA LEAVES INTERNATIONAL HOCKEY". IIHF.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Coffey, p. 59

- 1 2 3 4 5 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #17–Protesting amateur rules, Canada leaves international hockey Archived 27 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #67–The perfect game against the best team: Czechoslovaks–Soviets 7–2 Archived 13 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #97–B Pool Americans win Olympic silver in 1972 Archived 28 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 The Official Report of XIth Winter Olympic Games, Sapporo 1972 (PDF). The Organizing Committee for the Sapporo Olympic Winter Games. 1973. pp. 228–229. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Neumann, Bertl (ed.). XII. Olympische Winterspiele Innsbruck 1976 Final Report (PDF). Organizing Committee for the XIIth Winter Olympic Games 1976 at Innsbruck. p. 163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks 1997, p. 130

- ↑ Roberts, Selena (9 February 2002). "Olympics: Opening ceremony; Games Begin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "The 20th Century Awards: Sports Illustrated honors world's greatest athletes". Sports Illustrated. 3 December 1999. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "Top Story of the Century". International Ice Hockey Federation. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ Official Report of the Organising Committee of the XlVth Winter Olympic Games 1984 at Sarajevo (PDF). Sarajevo: Oslobodenje. 1984. p. 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #95–1988 Olympic silver – Finland is finally a true hockey power Archived 13 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #89–Finally, there's a real final game, The IIHF adopts a playoff system Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #58–Raimo Helminen, 38, dresses for a sixth Olympics Archived 10 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #65–Igor Larionov openly revolts against coach, system Archived 13 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Duhatschek, Eric (18 June 1989). "GMs figure Soviets one day will flood market". Calgary Herald. p. E4.

- ↑ Sweeping Changes. Sports Illustrated. 27 September 2002. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #42–Breakup of old Europe creates a new hockey world Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #59–Team with no name wins Olympic gold Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #77–Recently separated, Czechs and Slovaks meet in World Championships final Archived 13 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Judd 2008, p. 121

- ↑ O'Connor, Joe (28 February 2009). "Owning the moment". National Post. International Ice Hockey Federation. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ↑ Howard, Johnette (28 February 1994). "Sweden Wins on Forsberg's Shot in Shootout". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ Simmons, Steve (2006). "Medal for Mats". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #14–"Foppa" – The goal, the stamp & Sweden's first Olympic gold Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 Lapointe, Joe (16 September 1997). "The N.H.L.'s Olympic Gamble; Stars' Participation in Nagano Could Raise Sport's Profile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #12–Hasek thwarts all five Canadian gunners in epic shootout Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Farber, Michael (25 February 1998). "Was It Worth It?". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.