| Igbo | |

|---|---|

| Ásụ̀sụ́ Ìgbò | |

| Pronunciation | [ìɡ͡bò] |

| Native to | Nigeria |

| Region | Igboland: Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, Delta, Rivers[1] |

| Ethnicity | Igbo |

Native speakers | 31 million (2020)[1] |

Niger–Congo?

| |

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects | Isu, Aguata, Aguleri, Arochukwu, Awka, Anioma, Bende, Edda, Egbema, Ekpeye, Enuani, Etche, Ezza, Idemili, Igbanke, Ika, Ikwerre, Isobo, Izzi, Mbaise, Ndoki, Ngwa, Nkanu, Nnewi, Nsukka, Ohaji, Ogba, Ohafia, Ohuhu, Okigwe, Owerri, Ukwuani, Waawa[3] |

| Latin (Önwu alphabet) Nwagu Aneke script Neo-Nsibidi Ndebe script Igbo Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Society for Promoting Igbo Language and Culture (SPILC) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ig |

| ISO 639-2 | ibo |

| ISO 639-3 | ibo |

| Glottolog | nucl1417 |

| Linguasphere | 98-GAA-a |

Linguistic map of Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. Igbo is spoken in southern Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea. | |

| People | Ṇ́dị́ Ìgbò |

|---|---|

| Language | Ásụ̀sụ́ Ìgbò |

| Country | Àlà Ị̀gbò |

Igbo (English: /ˈiːboʊ/ EE-boh,[5] US also /ˈɪɡboʊ/ IG-boh;[6][7] Igbo: Ásụ̀sụ́ Ìgbò [ásʊ̀sʊ̀ ìɡ͡bò] ⓘ) is the principal native language cluster of the Igbo people, an ancient ethnicity in the Southeastern part of Nigeria.

The number of Igboid languages depends on how one classifies a language versus a dialect, so there could be around 35 different Igboid languages. The core Igbo cluster or Igbo proper is generally thought to be one language but there is limited mutual intelligibility between the different groupings (north, west, south and east). A standard literary language termed 'Igbo izugbe' (meaning "general igbo") was generically developed and later adopted around 1972, with its core foundation based on the Orlu (Isu dialects), Anambra (Awka dialects) and Umuahia (Ohuhu dialects), omitting the nasalization and aspiration of those varieties.

History

The first book to publish Igbo terms was History of the Mission of the Evangelical Brothers in the Caribbean (German: Geschichte der Mission der Evangelischen Brüder auf den Carabischen Inseln), published in 1777.[8] Shortly afterwards in 1789, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano was published in London, England, written by Olaudah Equiano, who was a former slave, featuring 79 Igbo words.[8] The narrative also illustrated various aspects of Igbo life in detail, based on Equiano's experiences in his hometown of Essaka.[9] Following the British Niger Expeditions of 1854 and 1857, a primer coded by a young Igbo missionary named Simon Jonas, was published by Ajayi Crowther in 1857.[10]

The language was standardized in church usage by the Union Igbo Bible (1913).[11]

Central Igbo, is based on the dialects of two members of the Ezinifite group of Igbo in Central Owerri Province between the towns of Owerri and Umuahia in Eastern Nigeria. From its proposal as a literary form in 1939 by Dr. Ida C. Ward, it was gradually accepted by missionaries, writers, and publishers across the region.

Standard Igbo aims to cross-pollinate Central Igbo with words from other Igbo dialects, with the adoption of loan words.[8]

Chinua Achebe passionately denounced language standardization efforts, beginning with Union Igbo through to Central and finally Standard Igbo, in a 1999 lecture sponsored by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese in Owerri.[12][13]

Distribution

Igbo (and its dialects) is the dominant language in the following Nigerian states:[3]

- Abia State

- Anambra State

- Bayelsa State, ie.Ukwuani & Ogba

- Benue State

- Cross river State

- Ebonyi State

- Edo State, i.e, Ika

- Enugu State

- Imo State

- Northern Delta State

- Kogi state

- Rivers State

- Akwa ibom state,i.e, Ndoki

Vocabulary

Word classes

Lexical categories in Igbo include nouns, pronouns, numerals, verbs, adjectives, conjunctions, and a single preposition.[14] The meaning of na, the single preposition, is flexible and must be ascertained from the context. Examples from Emenanjo (2015) illustrate the range of meaning:

O

3sg

bì

live

n'Enugwū.

PREP-Enugwū

'He lives in Enugwū.'

O

3sg

bì

live

ebe

here

à

this

n'ogè

PREP-time

agha.

war

'He lived here during the time of the war.'

Ndị

people

Fàda

Catholic

kwènyèrè

believe

n'atọ̀

PREP-three

n'ime

PREP-inside

otù.

one

Igbo has an extremely limited number of adjectives in a closed class. Emenanjo (1978, 2015)[16][15] counts just eight, which occur in pairs of opposites: ukwu 'big', nta 'small'; oji 'dark', ọcha 'light'; ọhụrụ 'new', ochie 'old'; ọma 'good'; ọjọọ 'bad' (Payne 1990).[17] Adjectival meaning is otherwise conveyed through the use of stative verbs or abstract nouns.

Verbs, by far the most prominent category in Igbo, host most of the language's morphology and appear to be the most basic category; many processes can derive new words from verbs, but few can derive verbs from words of other classes.[15]

Igbo pronouns do not index gender, and the same pronouns are used for male, female and inanimate beings. So the sentence, ọ maka can mean "he, she or it is beautiful".

Phonology

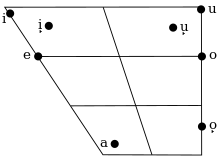

Vowels

Igbo is a tonal language. Tone varies by dialect but in most dialects there seem to be three register tones and three contour tones. The language's tone system was given by John Goldsmith as an example of autosegmental phenomena that go beyond the linear model of phonology laid out in The Sound Pattern of English.[18] Igbo words may differ only in tone. An example is ákwá "cry", àkwà "bed", àkwá "egg", and ákwà "cloth". As tone is not normally written, these all appear as ⟨akwa⟩ in print.

In many cases, the two (or sometimes three) tones commonly used in Igbo dictionaries fail to represent how words actually sound in the spoken language . This indicates that Igbo may have many more tones than previously recognised. For example, the imperative form of the word bia "come" has a different tone to that used in statement O bia "he came". That imperative tone is also used in the second syllable of abuo "two". Another distinct tone appears in the second syllable of asaa "seven" and another in the second syllable of aguu "hunger".

The language features vowel harmony with two sets of oral vowels distinguished by pharyngeal cavity size described in terms of retracted tongue root (RTR). These vowels also occupy different places in vowel space: [i ɪ̙ e a u ʊ̙ o ɒ̙] (the last commonly transcribed [ɔ̙], in keeping with neighboring languages). For simplicity, phonemic transcriptions typically choose only one of these parameters to be distinctive, either RTR as in the chart on the right and Igbo orthography (that is, as /i i̙ e a u u̙ o o̙/), or vowel space as in the alphabetic chart below (that is, as /i ɪ e a u ʊ o ɔ/). There are also nasal vowels.

Adjacent vowels usually undergo assimilation during speech. The sound of a preceding vowel, usually at the end of one word, merges in a rapid transition to the sound of the following vowel, particularly at the start of another word, giving the second vowel greater prominence in speech. Usually the first vowel (in the first word) is only slightly identifiable to listeners, usually undergoing centralisation. /kà ó mésjá/, for example, becomes /kòó mésjá/ "goodbye". An exception to this assimilation may be with words ending in /a/ such as /nà/ in /nà àlà/, "on the ground", which could be completely assimilated leaving /n/ in rapid speech, as in "nàlà" or "n'àlà". In other dialects however, the instance of /a/ such as in "nà" in /ọ́ nà èrí ńrí/, "he/she/it is eating", results in a long vowel, /ọ́ nèèrí ńrí/.[19]

Tone

The Igbo language is tonal in nature. This means that the meaning of a word can be altered depending on the tone used when pronouncing it. Igbo has two main tones: high and low. The high tone is usually marked with an acute accent (´) and the low tone is marked with a grave accent (`).

For example, the word ⟨akwa⟩ can mean "cry, egg, cloth, sew" depending on the tone used. If pronounced with a high tone on the first and last syllable it means "cry". But if pronounced with a low tone on the first syllable and high on the last syllable, it means "egg”. If it is pronounced with low tone on both syllables, then it will mean “cloth or sew”

Another example is the word "eze” which means "king or teeth". If pronounced with a high tone, it means "king". But if pronounced with a low tone, it means "teeth".

The use of tonal inflection in Igbo language is very important because it helps to differentiate between words that would otherwise sound the same. It can be challenging for English speakers to learn how to use the tones properly, but with practice, it can be mastered.

Consonants

Igbo does not have a contrast among voiced occlusives (between voiced stops and nasals): stops precede oral vowels, and nasals precede nasal vowels. Only a limited number of other consonants occur before nasal vowels, including /f, z, s/.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Labial– velar |

Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | ||||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | kʷ | k͡p | ||

| voiced | b~m | d | dʒ | ɡ~ŋ | ɡʷ~ŋʷ | ɡ͡b | |||

| Sonorant | l~n | j~ɲ | w | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | |||||

| voiced | z | ɣ | ɦ~ɦ̃ | ||||||

| Rhotic | ɹ | ||||||||

In some dialects, such as Enu-Onitsha Igbo, the doubly articulated /ɡ͡b/ and /k͡p/ are realized as a voiced/devoiced bilabial implosive. The approximant /ɹ/ is realized as an alveolar tap [ɾ] between vowels as in árá. The Enu-Onitsha Igbo dialect is very much similar to Enuani spoken among the Igbo-Anioma people in Delta State.

To illustrate the effect of phonological analysis, the following inventory of a typical Central dialect is taken from Clark (1990). Nasality has been analyzed as a feature of consonants, rather than vowels, avoiding the problem of why so few consonants occur before nasal vowels; [CjV] has also been analyzed as /CʲV/.[20]

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | Labial– velar |

Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | plain | lab. | ||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | pʲ | t | tɕ | k | kʷ | ɠ̊͡ɓ̥ | |

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ | pʲʰ | tʰ | tɕʰ | kʰ | kʷʰ | |||

| voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʑ | ɡ | ɡʷ | ɠ͡ɓ | ||

| voiced aspirated | bʱ | bʲʱ | dʱ | dʑʱ | ɡʱ | ɡʷʱ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ||||||

| voiceless nasalized | f̃ | s̃ | |||||||

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ɣʷ | |||||

| voiced nasalized | ṽ | z̃ | |||||||

| Rhotic | plain | r | |||||||

| nasalized | r̃ | ||||||||

| Approximant | voiceless | j̊ | w̥ | h | |||||

| voiceless nasalized | j̊̃ | w̥̃ | h̃ | ||||||

| voiced | l | j | w | ||||||

Syllables are of the form (C)V (optional consonant, vowel) or N (a syllabic nasal). CV is the most common syllable type. Every syllable bears a tone. Consonant clusters do not occur. The semivowels /j/ and /w/ can occur between consonant and vowel in some syllables. The semi-vowel in /CjV/ is analyzed as an underlying vowel "ị", so that -bịa is the phonemic form of bjá 'come'. On the other hand, "w" in /CwV/ is analyzed as an instance of labialization; so the phonemic form of the verb -gwá "tell" is /-ɡʷá/.

Morphological typology

Igbo is an isolating language that exhibits very little fusion. The language is predominantly suffixing in a hierarchical manner, such that the ordering of suffixes is governed semantically rather than by fixed position classes. The language has very little inflectional morphology but much derivational and extensional morphology. Most derivation takes place with verbal roots.[15]

Extensional suffixes, a term used in the Igbo literature, refer to morphology that has some but not all characteristics of derivation. The words created by these suffixes always belong to the same lexical category as the root from which they are created, and the suffixes' effects are principally semantic. On these grounds, Emenanjo (2015) asserts that the suffixes called extensional are bound lexical compounding elements; they cannot occur independently, though many are related to other free morphemes from which they may have originally been derived.[15]

In addition to affixation, Igbo exhibits both partial and full reduplication to form gerunds from verbs. The partial form copies on the initial consonant and inserts a high front vowel, while the full form copies the first consonant and vowel. Both types are then prefixed with o-. For example, -go 'buy' partially reduplicates to form ògigo 'buying,' and -bu 'carry' fully reduplicates to form òbubu 'carrying'. Some other noun and verb forms also exhibit reduplication, but because the reduplicated forms are semantically unpredictable, reduplication in their case is not synchronically productive, and they are better described as separate lexical items.[15]

Grammatical relations

Igbo does not mark overt case distinctions on nominal constituents and conveys grammatical relations only through word order. The typical Igbo sentence displays subject-verb-object (SVO) ordering, where the subject is understood as the sole argument of an intransitive verb or the agent-like (external) argument of a transitive verb. Igbo thus exhibits accusative alignment.

It has been proposed, with reservations, that some Igbo verbs display ergativity on some level, as in the following two examples:[15]

Nnukwu

big

mmīri

water

nà-ezò

AUX-fall

n'iro.

PREP-outside

'Heavy rain is falling outside.'

Ọ

it

nà-ezò

AUX-fall

nnukwu

big

mmīri

water

n'iro.

PREP-outside

'Heavy rain is falling outside.'

In (4), the verb has a single argument, nnukwu mmīri, which appears in subject position, and in the transitive sentence (5), that same argument appears in the object position, even though the two are semantically identical. On this basis, authors such as Emenanjuo (2015) have posited that this argument is an absolutive and that Igbo therefore contains some degree of ergativity.

However, others disagree, arguing that the relevant category is not alignment but underlying argument structure; under this hypothesis, (4) and (5) differ only in the application of a transformation and can be accounted for entirely by the unaccusative hypothesis and the Extended Projection Principle;[21] the nominal argument is generated in object position, and either it is raised to the subject position, as in (4), or the subject position is filled with a pleonastic pronoun, as in (5).

Relative clauses

Igbo relative clauses are externally headed and follow the head noun. They do not employ overt relative markers or resumptive pronouns, instead leaving a gap in the position of the relativized noun. Subjects and objects can be relativized. Examples include (relative clauses bracketed):[15]

Ọ

3sg

zụ̀-tà-rà

buy-SUFF-PRF

àkwa

egg

[mā-ra

[be.good-PRF

mmā].

goodness]

'She bought eggs that are good.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Àkwa

egg

[ọ

[3sg

zụ̀-tà-rà]

buy-SUFF-PRF]

mà-rà

good-PRF

mmā.

goodness

'The eggs that she bought are good.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Voice and valence

Igbo lacks the common valence-decreasing operation of passivization, a fact which has led multiple scholars to claim that "voice is not a relevant category in Igbo."[15] The language does, however, possess some valence-increasing operations that could be construed as voice under a broader definition

Ógù

Ogu

a-vó-ọ-la

PREF-be.open-SUFF-PRF

'Ogu has become disgraced.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Íbè

Ibe

e-mé-vọ-ọ-la

PREF-make-be.open-SUFF-PRF

Ogù.

Ogu

'Ibe has disgraced Ogu.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Àfe

clothes

isé

five

kò-ro

hang-PRF

n'ezí.

PREP-compound

'Five items of clothing are hanging in the compound.'

Ókwu

Okwu

kò-we-re

hang-INCH-PRF

afe

clothes

isé

five

n'ezi.

PREP-compound

'Okwu hung five items of clothing in the compound.'

Igbo also possess an applicative construction, which takes the suffix -rV, where V copies the previous vowel, and the applicative argument follows the verb directly. The applicative suffix is identical in form with the past tense suffix, with which it should not be confused.[14] For example:[21]

Íbè

Ibe

nye-re-re

give-PRF-APPL

m

1sg

Ógù

Ogu

ákwụkwọ.

book

'Ibe gave the book to Ogu for me.'

Verb serialization

Igbo permits verb serialization, which is used extensively to compensate for its paucity of prepositions. Among the meaning types commonly expressed in serial verb constructions are instruments, datives, accompaniment, purpose, and manner. (13) and (14) below illustrate instrumental and dative verb series, respectively:[15]

Ọ

3sg

nà-èji

AUX-PREF-use

mmà

knife

à-bacha

PREF-peel

jī.

yam

'He peels yams with a knife.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Ọ

3sg

zụ̀-tà-rà

buy-SUFF-PRF

akwụkwọ

book

nye

give

m̄.

1sg

'He bought a book and gave it to me.' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

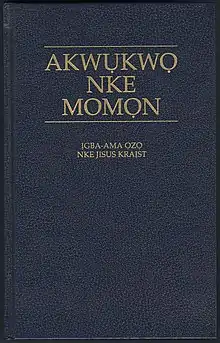

Writing system

The Igbo people have long used Nsibidi ideograms, invented by the neighboring Ekoi people, for basic written communication.[22] They have been used since at least the 16th century, but died out publicly after they became popular amongst secret societies such as the Ekpe, who used them as a secret form of communication.[23] Nsibidi, however, is not a full writing system, because it cannot transcribe the Igbo language specifically. In 1960, a rural land owner and dibia named Nwagu Aneke developed a syllabary for the Umuleri dialect of Igbo, the script, named after him as the Nwagu Aneke script, was used to write hundreds of diary entries until Aneke's death in 1991. The Nwagu Aneke Project is working on translating Nwagu's commentary and diary.[24]

History of Igbo orthography

Before the existence of any official system of orthography for the Igbo language, travelers and writers documented Igbo sounds by utilizing the orthologies of their own languages in transcribing them, though they encountered difficulty representing particular sounds, such as implosives, labialized velars, syllabic nasals, and non-expanded vowels. In the 1850s, German philologist Karl Richard Lepsius published the Standard Alphabet, which was universal to all languages of the world, and became the first Igbo orthography. It contained 34 letters and included digraphs and diacritical marks to transcribe sounds distinct to African languages.[25] The Lepsius Standard Alphabet contained the following letters:

- a b d e f g h i k l m n o p r s t u v w y z gb gh gw kp kw ṅ nw ny ọ s ds ts[25]

The Lepsius orthography was replaced by the Practical Orthography of African Languages (Africa Orthography) in 1929 by the colonial government in Nigeria. The new orthography, created by the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures (IIALC), had 36 letters and disposed of diacritic marks. Numerous controversial issues with the new orthography eventually led to its replacement in the early 1960s.[25] The Africa Orthography contained the following letters:

- a b c d e f g gb gh h i j k kp l m n ŋ ny o ɔ ɵ p r s t u w y z gw kw nw[25]

Ọnwụ

The current Ọnwụ alphabet, a compromise between the older Lepsius alphabet and a newer alphabet advocated by the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures (IIALC), is presented in the following table, with the International Phonetic Alphabet equivalents for the characters:[26]

| Letter | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| A a | /a/ |

| B b | /b/ |

| Ch ch | /tʃ/ |

| D d | /d/ |

| E e | /e/ |

| F f | /f/ |

| G g | /ɡ/ |

| Gb gb | /ɡ͡b~ɠ͡ɓ/ |

| Gh gh | /ɣ/ |

| Gw gw | /ɡʷ/ |

| H h | /ɦ/ |

| I i | /i/ |

| Ị ị | /ɪ̙/ |

| J j | /dʒ/ |

| K k | /k/ |

| Kp kp | /k͡p~ƙ͡ƥ/ |

| Kw kw | /kʷ/ |

| L l | /l/ |

| M m | /m/ |

| N n | /n/ |

| Ṅ ṅ | /ŋ/ |

| Nw nw | /ŋʷ/ |

| Ny ny | /ɲ/ |

| O o | /o/ |

| Ọ ọ | /ɔ̙/ |

| P p | /p/ |

| R r | /ɹ/ |

| S s | /s/ |

| Sh sh | /ʃ/ |

| T t | /t/ |

| U u | /u/ |

| Ụ ụ | /ʊ̙/ |

| V v | /v/ |

| W w | /w/ |

| Y y | /j/ |

| Z z | /z/ |

The graphemes ⟨gb⟩ and ⟨kp⟩ are described both as coarticulated /ɡ͡b/ and /k͡p/ and as implosives, so both values are included in the table.

⟨m⟩ and ⟨n⟩ each represent two phonemes: a nasal consonant and a syllabic nasal.

Tones are sometimes indicated in writing, and sometimes not. When tone is indicated, low tones are shown with a grave accent over the vowel, for example ⟨a⟩ → ⟨à⟩, and high tones with an acute accent over the vowel, for example ⟨a⟩ → ⟨á⟩.

Other orthographies

A variety of issues have made agreement on a standardized orthography for the Igbo language difficult. In 1976, the Igbo Standardization Committee criticized the official orthography in light of the difficulty notating diacritic marks using typewriters and computers; difficulty in accurately representing tone with tone-marking conventions, as they are subject to change in different environments; and the inability to capture various sounds particular to certain Igbo dialects. The Committee produced a modified version of the Ọnwụ orthography, called the New Standard Orthography, which substituted ⟨ö⟩ and ⟨ü⟩ for ⟨ọ⟩ and ⟨ụ⟩, ⟨c⟩ for ⟨ch⟩, and ⟨ñ⟩ for ⟨ṅ⟩.[27] The New Standard Orthography has not been widely adopted, although it was used, for example, in the 1998 Igbo English Dictionary by Michael Echeruo.

More recent calls for reform have been based in part on the rogue use of alphabetic symbols, tonal notations, and spelling conventions that deviate from the standard orthography.[25]

There are also some modern movements to restore the use of and modernize nsibidi as a writing system,[28][29] which mostly focus on Igbo as it is the most populous language that used to use nsibidi.

Ndebe Script

In 2009, a Nigerian software engineer and artist named Lotanna Igwe-Odunze developed a native script named Ndebe script. It was further redesigned and relaunched in 2020 as a standalone writing system completely independent of Nsibidi.[30][31] The script gained notable attention after a write-up from Nigerian linguist Kola Tubosun on its "straightforward" and "logical" approach to indicating tonal and dialectal variety compared to Latin.[30][32]

Proverbs

Proverbs and idiomatic expressions (ilu and akpalaokwu in Igbo, respectively) are highly valued by the Igbo people and proficiency in the language means knowing how to intersperse speech with a good dose of proverbs. Chinua Achebe (in Things Fall Apart) describes proverbs as "the palm oil with which words are eaten". Proverbs are widely used in the traditional society to describe, in very few words, what could have otherwise required a thousand words. Proverbs may also become euphemistic means of making certain expressions in the Igbo society, thus the Igbo have come to typically rely on this as avenues of certain expressions.[33]

Usage in the diaspora

As a consequence of the Atlantic slave trade, the Igbo language was spread by enslaved Igbo people throughout slave colonies in the Americas. Examples can be found in Jamaican Patois: the pronoun /unu/, used for 'you (plural)', is taken from Igbo, Red eboe refers to a fair-skinned black person because of the reported account of a fair or yellowish skin tone among the Igbo.[34] Soso meaning only comes from Igbo.[35] See List of Jamaican Patois words of African origin for more examples.

The word Bim, a name for Barbados, was commonly used by enslaved Barbadians (Bajans). This word is said to derive from the Igbo language, derived from bi mu (or either bem, Ndi bem, Nwanyi ibem or Nwoke ibem) (English: My people),[36][37] but it may have other origins (see: Barbados etymology).

In Cuba, the Igbo language (along with the Efik language) continues to be used, albeit in a creolized form, in ceremonies of the Abakuá society, equivalent or derived from the Ekpe society in modern Nigeria.

In modern times, Igbo people in the diaspora are putting resources in place to make the study of the language accessible.

Present state

There are some discussions as to whether the Igbo language is in danger of extinction, advanced in part by a 2006 UNESCO report that predicted the Igbo language will become extinct within 50 years.[38] Professor of African and African Diaspora Literatures at University of Massachusetts, Chukwuma Azuonye, emphasizes indicators for the endangerment of the Igbo language based on criteria that includes the declining population of monolingual elderly speakers; reduced competence and performance among Igbo speakers, especially children; the deterioration of idioms, proverbs, and other rhetorical elements of the Igbo language that convey the cultural aesthetic; and code-switching, code-mixing, and language shift.[39]

External and internal factors have been proposed as causes for the decline of the Igbo language and its usage. Preference for the English language in post-colonial Nigeria has usurped the Igbo language's role and function in society,[39] as English is perceived by Igbo speakers as the language of status and opportunity.[39] This perception may be a contributor to the negative attitude towards the Igbo language by its speakers across the spectrum of socio-economic classes.[38] Igbo children's reduced competence and performance has been attributed in part to the lack of exposure in the home environment, which impacts intergenerational transmission of the language.[39] English is the official language in Nigeria and is utilized in government administration, educational institutions, and commerce. Aside from its role in numerous facets of daily life in Nigeria, globalization exerts pressure to utilize English as a universal standard language in support of economic and technological advancement.[38] A 2005 study by Igboanusi and Peter demonstrated the preferential attitude towards English over the Igbo language amongst Igbo people in the communication, entertainment, and media domains. English was preferred by Igbo speakers at 56.5% for oral communication, 91.5% for written communication, 55.5–59.5% in entertainment, and 73.5–83.5% for media.[40]

The effect of English on Igbo languages amongst bilingual Igbo speakers can be seen by the incorporation of English loanwords into Igbo and code-switching between the two languages. English loanwords, which are usually nouns, have been found to retain English semantics, but typically follow phonological and morphological structures of Igbo. Lexical items conform to the vowel harmony intrinsic to Igbo phonological structures. For example, loanwords with syllable-final consonants may be assimilated by the addition of a vowel after the consonant, and vowels are inserted in between consonant clusters, which have not been found to occur in Igbo.[41] This can be seen in the word sukulu, which is a loanword derived from the English word school that has followed the aforementioned pattern of modification when it was assimilated into the Igbo language.[42] Code-switching, which involves the insertion of longer English syntactic units into Igbo utterances, may consist of phrases or entire sentences, principally nouns and verbs, that may or may not follow Igbo syntactic patterns. Igbo affixes to English verbs determine tense and aspectual markers, such as the Igbo suffix -i affixed to the English word 'check', expressed as the word check-i.[41]

The standardized Igbo language is composed of fragmented features from numerous Igbo dialects and is not technically a spoken language, but it is used in communicational, educational, and academic contexts. This unification is perceived by Chukwuma Azuonye as undermining the survival of Igbo by erasing diversity between dialects.[39] Each individual dialect possesses unique untranslatable idioms and rhetorical devices that represent Igbo cultural nuances that can be lost as dialects disappear or deteriorate.[39] Newly coined terms may fail to conform to a dialect's lexical formation in assimilating loan words.[39]

Proverbs are an essential component of the Igbo language that convey cultural wisdom and contextual significance to linguistic expression. Everyday usage of Igbo proverbs has declined in recent generations of speakers, which threatens loss in intergenerational transmission.[43] A recent study of the Ogwashi dialect of Igbo demonstrated a steep decline in youth's knowledge and use of proverbs compared to elder speakers.[39] In this study, youths employed simplified or incomplete proverbial expressions, lacked a diverse proverbial repertoire, and were deficient in their understanding of proper contextual usages as compared to elders who demonstrated competence to enhance linguistic expression with a diverse vocabulary of proverbs.[39]

Sample text

Ndị dere Oziọma ndị ahụ maara na Jisọs ebiwo ndụ n’eluigwe tupu ọ bịa n’ụwa.

The writers of those gospels knew that Jesus had lived in heaven before he came to earth.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Igbo at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ↑ Heusing, Gerald (1999). Aspects of the morphology-syntax interface in four Nigerian languages. LIT erlag Münster. p. 3. ISBN 3-8258-3917-6.

- 1 2 "Igbo Dialects and Igboid Languages". Okwu ID. 22 April 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- 1 2 "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - : Overview". UNHCR. 20 May 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Igbo". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ↑ "Igbo". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ↑ "Ibo". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- 1 2 3 Oraka, L. N. (1983). The Foundations of Igbo Studies: A Short History of the Study of Igbo Language and Culture. University Publishing Co. p. 21. ISBN 978-160-264-3.

- ↑ Equiano, Olaudah (1789). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. p. 9. ISBN 1-4250-4524-3.

- ↑ Oluniyi, Olufemi Olayinka (2017). Reconciliation in Northern Nigeria: The Space for Public Apology. Frontier Press. ISBN 9789789495276.

- ↑ Fulford, Ben (2002). "An Igbo Esperanto: A History of the Union Ibo Bible 1900-1950". Journal of Religion in Africa. 32 (4): 478. doi:10.1163/157006602321107658. JSTOR 1581603. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ Achebe, Chinua (1999). Tomorrow is Uncertain: Today is Soon Enough (Speech). Columbia University. Translated by Pritchett, Frances W. Owerri, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 25 December 2003. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ↑ Pritchett, Frances W. "A History of the Igbo Language". Columbia University. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- 1 2 Green, M. M.; Igwe, G. E. (1963). A Descriptive Grammar of Igbo. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: Institut für Orientforschung.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Emenanjo, Nolue (2015). A Grammar of Contemporary Igbo: Constituents, Features and Processes. Oxford: M and J Grand Orbit Communications.

- ↑ Emenanjo, Nolue (1978). Elements of Modern Igbo Grammar - a descriptive approach. Ibadan, Nigeria: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Payne, JR (1990). "Language Universals and Language Types". In Collinge (ed.). An Encyclopedia of Language.

- ↑ Goldsmith, John A. (June 1976). Autosegmental Phonology (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2005.

- ↑ Welmers, William Everett (1974). African Language Structures. University of California Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0520022106.

- ↑ Clark, Mary M. (1990). The Tonal System of Igbo. doi:10.1515/9783110869095. ISBN 9783110130416.

- 1 2 Nwachukwu, P. Akujuoobi (September 1987). "The Argument Structure of Igbo Verbs" (PDF). Lexicon Project Working Papers. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2023.

- ↑ "Nsibidi". National Museum of African Art. Smithsonian Institution.

Nsibidi is an ancient system of graphic communication indigenous to the Ejagham peoples of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon in the Cross River region. It is also used by neighboring Ibibio, Efik and Igbo peoples.

- ↑ Oraka, Louis Nnamdi (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co. pp. 17, 13. ISBN 978-160-264-3.

- ↑ Azuonye, Chukwuma (1992). "The Nwagu Aneke Igbo Script: Its Origins, Features and Potentials as a Medium of Alternative Literacy in African Languages". Africana Studies Faculty Publication Series. University of Massachusetts Boston (13).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ohiri-Aniche, Chinyere (2007). "Stemming the tide of centrifugal forces in Igbo orthography". Dialectical Anthropology. 31 (4): 423–436. doi:10.1007/s10624-008-9037-x. S2CID 144568449 – via Hollis.

- ↑ Awde, Nicholas; Wambu, Onyekachi (1999). Igbo Dictionary & Phrasebook. New York: Hippocrene Books. pp. 27. ISBN 0781806615.

- ↑ Oluikpe, Esther N. (27 March 2014). "Igbo language research: Yesterday and today". Language Matters. 45 (1): 110–126. doi:10.1080/10228195.2013.860185. S2CID 145580712.

- ↑ "Nsibidi". blog.nsibiri.org.

- ↑ "Update on the Ndebe Igbo Writing System". Sugabelly. 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 Tubosun, Kola (13 July 2020). "Writing Africa's Future in New Characters". Popula.

- ↑ "Nigerian Woman, Lotanna Igwe-Odunze, Invents New Writing System For Igbo Language". Sahara Reporters. 5 July 2020.

- ↑ Elusoji, Solomon (3 October 2020). "The Igbo Language Gets Its Own Modern Script, But Will It Matter?". Channels Television. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Nwagbo, Osita Gerald (2021). "Sexual Taboos and Euphemisms in Igbo: An Anthropolinguistic Appraisal" (PDF). Language in Africa. 2 (3): 112–148. doi:10.37892/2686-8946-2021-2-3-112-148.

- ↑ Cassidy, Frederic Gomes; Le Page, Robert Brock (2002). A Dictionary of Jamaican English (2nd ed.). University of the West Indies Press. p. 168. ISBN 976-640-127-6. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ McWhorter, John H. (2000). The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-21999-6. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ↑ Allsopp, Richard; Jeannette Allsopp (2003). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Contributor Richard Allsopp. University of the West Indies Press. p. 101. ISBN 976-640-145-4. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Carrington, Sean (2007). A~Z of Barbados Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean Publishers Limited. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-333-92068-8.

- 1 2 3 Asonye, Emma (2013). "UNESCO Prediction of the Igbo Language Death: Facts and Fables" (PDF). Journal of the Linguistic Association of Nigeria. 16 (1 & 2): 91–98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Azuonye, Chukwuma (2002). "Igbo as an Endangered Language". Africana Studies Faculty Publication Series. 17: 41–68.

- ↑ Igboanusi, Herbert (2008). "Is Igbo an endangered language?". Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication. 25 (4): 443–452. doi:10.1515/MULTI.2006.023. S2CID 145225091.

- 1 2 Akere, Funso (1981). "Sociolinguistic consequences of language contact: English versus Nigerian Languages". Language Sciences. 3 (2): 283–304. doi:10.1016/S0388-0001(81)80003-4.

- ↑ Ikekeonwu, Clara I. (Winter 1982). "Borrowings and Neologisms in Igbo". Anthropological Linguistics. 24 (4): 480–486. JSTOR 30027647.

- ↑ Emeka-Nwobia, Ngozi Ugo (2018), Brunn, Stanley D; Kehrein, Roland (eds.), "Language Endangerment in Nigeria: The Resilience of Igbo Language", Handbook of the Changing World Language Map, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–13, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73400-2_33-1, ISBN 978-3-319-73400-2, S2CID 158553159

References

- Awde, Nicholas and Onyekachi Wambu (1999) Igbo: Igbo–English / English–Igbo Dictionary and Phrasebook New York: Hippocrene Books.

- Emenanjo, 'Nolue (1976) Elements of Modern Igbo Grammar. Ibadan: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-154-078-8

- Emenanjo, Nolue. A Grammar of Contemporary Igbo: Constituents, Features and Processes. Oxford: M and J Grand Orbit Communications, 2015.

- Green, M.M. and G.E. Igwe. 1963. A Descriptive Grammar of Igbo. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: Institut für Orientforschung.

- Ikekeonwu, Clara (1999), "Igbo", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, Cambridge University Press, pp. 108–110, ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- Nwachukwu, P. Akujuoobi. 1987. The argument structure of Igbo verbs. Lexicon Project Working Papers 18. Cambridge: MIT.

- Obiamalu, G.O.C. (2002) The development of Igbo standard orthography: a historical survey in Egbokhare, Francis O. and Oyetade, S.O. (ed.) (2002) Harmonization and standardization of Nigerian languages. Cape Town : Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society (CASAS). ISBN 1-919799-70-2

- Surviving the iron curtain: A microscopic view of what life was like, inside a war-torn region by Chief Uche Jim Ojiaku, ISBN 1-4241-7070-2; ISBN 978-1-4241-7070-8 (2007)