| Efik | |

|---|---|

| Usem Efịk | |

| Native to | Southern Nigeria |

| Region | Cross River State |

| Ethnicity | Efik |

Native speakers | 698 620 (2020)[1] Second language: 2 million[1] |

| Latin Nsibidi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | efi |

| ISO 639-3 | efi |

| Glottolog | efik1245 |

Efik /ˈɛfɪk/ EF-ik[2] (Usem Efịk) is the indigenous language of the Efik people, who are situated in the present-day Cross River state and Akwa Ibom state of Nigeria, as well as in the North-West of Cameroon. The Efik language is mutually intelligible with other lower Cross River languages such as Ibibio, Annang, Oro and Ekid but the degree of intelligibility in the case of Oro and Ekid is unidirectional; in other words, speakers of these languages speak and understand Efik (and Ibibio) but not vice versa.[3] The Efik vocabulary has been enriched and influenced by external contact with the British, Portuguese and other surrounding communities such as Balondo, Oron, Efut, Okoyong, Efiat and Ekoi (Qua).[4][5]

Classification

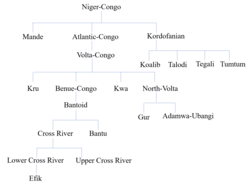

The Efik Language has undergone several linguistic classifications since the 19th century. The first attempt at classifying the Efik Language was by Dr. Baikie in 1854.[6][7] Dr Baikie had stated, "All the coast dialects from One to Old Kalabar, are, either directly or indirectly, connected with Igbo, which later Dr. Latham informed that, it is certainly related to the Kafir class".[6] The Kafir Class was a derogatory term used to describe the Bantu languages.[8] Thus, Dr Baikie attempts to classify the Efik Language as linked to the Bantu languages. The next attempt to classify the Efik language was by Rev. Hugh Goldie who classified the Efik Language as one of the Northern Languages which he states, "forms by far the greater part of its as the Semitic class does, from the root of the verb."[9] Another attempt was made by Westermann who classified the Efik languages as belonging to the West Sudan group of the Sudanic languages. The present linguistic classification was made by Greenberg who groups Efik in the Benue-Congo sub-family of the Niger-Congo family.[10] One of the criteria of the inclusion of the Efik language into the Niger-Congo family is its morphological feature. According to Greenberg, "the trait of the Niger-Congo morphology which provides the main material for comparison is the system of noun classification by pair of affixes."[10] Due to the large number of synonyms in the Efik vocabulary, scholars like Der-Houssikian criticised Greenberg's linguistic classification stating, "Ten of the Efik entries have in Goldie's dictionary several synonyms. This immediately brings up the possibility of differing connotations and nuances of meaning. Such differences are not defined by Goldie. These exceptions reduce the number of non-suspicious itens from 51 to 36."[11] Faraclass in his study of Cross River Languages, classified the Efik language as a member of the Lower Cross sub-group of the Delta-Cross group which is an extension of the larger Cross River group that is a major constituent of the Benue Congo subfamily.[12]

History

Written Efik

The Efik language was first put into writing in 1812 by Chief Eyo Nsa, also known as Willy Eyo Honesty.[13] The following words were obtained from Chief Eyo Nsa by G. A. Robertson:[13]

| Eyo's vocabulary | Modern Efik | English |

|---|---|---|

| hittam | itam | 'hat' |

| hecat | ikọt | 'bush' |

| henung | inụñ | 'salt' |

| erto | eto | 'tree' |

| wang | ñwan | 'woman' |

| erboir | ebua | 'dog' |

| heuneck | unek | 'dance' |

Prior to the documenting of words in the Efik language by Chief Eyo Nsa, several traders in old Calabar could read and write and had kept journals albeit in the English language.[14] The earliest written letter from the chiefs of Old Calabar dates to 1776.[15][14] Thus, the literary ground for the Efik language had already been prepared prior to the arrival of the missionaries. When the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland Mission arrived Old Calabar in 1846, Reverend Hope Waddell and Samuel Edgerley with the assistance of the Efik trader Egboyoung (Ekpenyong) started the recordings of Efik vocabulary; these were printed in their lithographic press and made ready in 1849.[16] On the arrival of the missionaries, there was the problem of creating an appropriate orthography for the Efik Language. The orthography chosen by the missionaries was developed by Dr. Lepsius whose system and the phonetic alphabet were found to be suitable for the Efik language at the time.[17] The first Efik dictionary was later released in 1862 by Rev. Hugh Goldie and the Efik orthography was developed in 1874 by Goldie.[16] The Efik language flourished in written literature in which the missionaries and the Efik respectively, played a leading role.[18] Early religious works translated in the Efik language included The Old Testament which was completed by Alexander Robb in 1868 and printed in 1873; Paul's Epistle to the Hebrews translated and published by William Anderson.[19] Indigenous ministers equally contributed to the expansion of the Efik religious literature. Reverend Esien Esien Ukpabio, the first Efik minister ordained in 1872, translated into Efik, Dr. J.H. Wilson's "The gospel and its fruits".[18] Asuquo Ekanem who was equally an Efik minister translated John Bunyan's Holy war into Efik.[18] The Efik people equally began to write Church hymns and publish them. William Inyang Ndang who had spent some time in Britain was the first Efik to introduce a choir into churches at Calabar and had contributed to a large number of Church hymns together with his wife, Mrs Jane Ndang.[18][20] Between the 1930s to 1950s, Magazines, Newspapers and periodicals were published in the Efik language. From the early 1930s, there was a twelve-page quarterly magazine in Efik, "Obụkpọn Obio" (Town Bugle) edited by Reverend James Ballantyne.[18] The work was designed for the general reader and featured a range of topics, from Usuhọde ye Uforo Obio (The decline and prosperity of a town) to Ufọk Ndọ (Matrimonial home) and other similar topics.[18] This was followed in the 1940s by "Uñwana" (light), a monthly periodical of 32 pages, edited by E.N. Amaku.[18] From 1948 to 1950, an eight-page weekly newspaper in Efik, "Obodom Edem Usiahautin" (Eastern Talking Drum), edited by Chief Etim Ekpenyong and printed at the Henshaw Press was sold at 2d each.[21] It supplied regular world news (Mbụk ñkpọntibe ererimbuot) and was widely read.[21] Thus, the Efik language has enjoyed a lot of scholarship since the arrival of the Christian missionaries in 1846.[16]

Spread of the Efik Language

_(14753380296).jpg.webp)

Due to the extensive trading activities of the Efik people, the language became the lingua franca of the Cross River region.[4] According to Offiong and Ansa,

The Efik language over the years has developed to a level that it dominates other languages spoken around Cross River State. A language like the Kiong language spoken by the Okoyong people is extinct because its speakers have imbibed the Efik language over the years. The same is also said of the Efut language spoken by the Efut people in Calabar South, Apart from being the language that is spoken by a third of Cross River State as an L1, it is the L2 or L3 of most Cross River indigenes. For the purpose of advertising, the language is most used after English in the state. Television and Radio commercials are aired everyday in different spheres, In politics the language is used by all in the Southern senatorial and parts of the Central Senatorial Districts of the State. In education, there is a primary and secondary curriculum of Efik in schools. In the development of linguistics, it is studied at the undergraduate level in the University of Calabar.[22]

Among the Ibibio, the Efik language was accepted as the language of literature due to a translation of the Bible into Efik by the Church of Scotland mission.[4] The Efik Language equally survived in the West Indies due to the exportation of slaves from the Cross River Region. Words of Efik origin can be found in the vocabulary of the Gullah Geechee people of the United States.[23] Within the diaspora in Cuba, a creolised form of the Efik Language is used in the Abakuá secret society, which has its roots in the Efik Ekpe secret society in Nigeria.[24]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Labio-velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiced | b | d | ||||

| voiceless | t | k | k͡p | ||||

| Fricative | f | s | h | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||||

| Semivowels | j | w | |||||

Allophones

/b/ has several allophones.[25][27] These allophones are dependent on the position of /b/ in a word.[25] In final positions it occurs as an unreleased stop phonetically represented as [p̚] , as in the following imperative verbs. [kop̚] (listen!), [sɔp̚] (quick!), [fɛp̚] (dodge!).[25] /p/ in Efik is only found in final positions and can only be realised as /β/ in intervocalic position, example; [dép] + [úfɔk] = [déβúfɔk].[28] If it is, however, immediately followed by a consonant, it occurs as a released stop phonetically, as in these examples:[29]

- [i.kop.ke] (he hasn't heard)

- [n̩.dɛp.ke] (I haven't bought)

Like /b/, /t/ and /k/ are unreleased in final positions.[29] Thus, phonetically we have the following:[29]

- [bɛt̚] (wait)

- [dɔk̚] (dig)

/k/ has other allophones.[29] If it is preceded by a high front vowel, it is phonetically [g], as in these examples:[29]

- [digi] (trample)

- [idigɛ] (it is not)

- [tiga] (shoot, kick)

If, however, it occurs between two mid front vowels, or two low central vowels, it is phonetically [ɣ] or [x] , as in the following:[29]

- [fɛxɛ] (run)

- [daɣa] (leave, go away)

- [g] is sometimes found in initial positions as in loan words such as "Garri". However, pronunciations with [k] and [ŋk] also occur.

/d/ has an allophone [ɾ], which can occur in free between vowels, as in the following examples:[30]

- [adan] or [aɾan] (oil)

- [odo] or [oɾo] (the/that)

When the preceding vowel itself is preceded by a stop or fricative, it is deleted, and the /d/ always occurs as [ɾ]. Examples include:

- /tidɛ/ [tɾɛ] (stop)

- /k͡pidɛ/ [k͡pɾɛ] (be small)

- /fadaŋ/ [fɾaŋ] (fry)

When a nasal occurs initially and before another consonant, it is syllabic.

- [m̩bak̚] (part)

- [n̩tan] (sand)

- [ŋ̍k͡pɔ] (something)

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Vowels in Efik vary phonetically depending on whether they occur between consonants (i.e. in closed syllables) or not.[31] Vowels in closed syllables are shorter and more centralized than those in open syllables.[31] Thus /i, u/ are highly centralized as [ɨ, ʉ] in the following:[31]

- [ɲɨk̚] (push or press someone to do something)

- [bʉt̚] (shame)

As /i/ is a front vowel, centralization involves a position further back while in the case of /u/, a back vowel, centralization involves a position further front in the mouth.[31]

Semi-vowels

The semi-vowels /w/ and /j/ behave like consonants, as the following show:[32]

- /wak/ (tear up)

- /awa/ (a green plant)

- /jom/ (look for, search)

- /ajaŋ/ (broom)[32]

When they are preceded by a consonant, they sound like /u/ and /i/ respectively, as these examples show:[32]

| Phonemic | Phonetic |

|---|---|

| /udwa/ | [udua] (market) |

| /dwɔ/ | [duɔ] (fall) |

| /bjom/ | [biom] (carry on the head) |

| /fjob/ | [fiop̚] (to be hot)[31] |

Tones

Oral Efik is predominantly tonal in structure, and this is essentially the pitch of the voice in saying a word or syllable of a word [33] A word may have two or more meanings depending on the tonal response of the speaker.[34] Examples include: Ákpá - River, Àkpá - First and Àkpà - Stomach. In Efik, there are five different tone marks that aid in the definition of the meaning of words:[34]

- High Tone defined by (⸝)

- Low Tone defined by (⸜)

- Mid Tone defined by (–)

- Falling Tone defined by (∧)

- Rising Tone defined by (∨)

Vocabulary

The Efik vocabulary has continually expanded since the earliest contact with surrounding ethnicities and European traders.[4] Although, Professor Mervyn D. W. Jeffreys argues that "Efik is far poorer in its vocabulary than Ibibio", Donald C. Simmons counters this statement argueing that there is no evidence to support Jeffreys statement.[35][4] Due to its geographical position along the Lower Cross River, the Efik language adopted foreign words. The Efik dictionaries of Goldie, Aye and Adams reveal some words of Efut, Qua and Igbo origin adopted into the Efik Language. Words of Efut and qua origin exist in the Efik vocabulary by virtue of their long history of intermarriages and interethnic trade.[4] Words of Igbo origin such as "Amasi" denote a servant-master relationship and would have been obtained due to the former status of the Igbo in Efik society.[36]

Word origins

The Efik Language besides making new words from Efik verbs and other pre-existing words, further borrows words from other languages. Several words in the Efik vocabulary were equally borrowed from European languages such as Portuguese and English.[37] According to Simmons, "Efik words applied to European-introduced innovations consist of single words extended in meaning to include new concepts or material objects, and secondary formations constituting new combinations of primary morphemes. Words denoting material objects which history relates Europeans introduced at an early date, are uñwọñ - Tobacco and snuff, lbokpot 'maize' and probably, lwa 'cassava'."[37] Religious and educational terms can be dated to 1846 when the Scottish missionaries arrived Old Calabar and began their mission.[38] According to Simmons, "Efik frequently designate an introduced object with the name of the group from whom they obtained it used as a noun in genitive relationship together with the noun which names the object".[39] The most common nouns used to identify specific groups include Mbakara (European), Oboriki (Portuguese), Unehe (Igbo), Asanu (Hausa), Ekoi, Ibibio. Compounds that illustrate this usage include "Oboriki Unen" (Portuguese Hen), "Utere Mbakara" (Turkey), Ikpọ Unehe (Igbo climbing rope), Okpoho Ibibio (the manilla, copper ring once used as currency in Ibibioland).[40][39]

Efik loanwords in other languages

Due to the peregrinations of Efik traders in the Cross River region and the Cameroons, the Efik language has bequeathed several words to the vocabulary of other languages within and outside Africa.[41][42][43] Efik words such as Utuenikañ (Lantern), Ñkanika (Bell or Clock), Enañukwak (Bicycle), Ñwed Abasi (Bible) can be found in several communities in the Old Eastern Region and the Cameroons. Nanji attests a school of thought that holds that forty percent of the Balondo Language consists of Efik words.[44] Julian Loperus in her book The Londo Word (1985) states,

The geographical position of the Balondo area, Just to the east of Cross River delta, also explains the rather large proportion of borrowed Efik. Ibibio and possibly other cross river languages. Not only do many Nigerians speaking these languages work in palm plantations in the Balondo area, but Calabar appears to be a centre of attraction for young people wishing to experience the outside world. The language has a certain social status. Efik proverbs are being quoted by Balondo speakers in public meetings.[44]

Several words of Efik origin can equally be found in English, such as Angwantibo, Buckra and Obeah.[45]

Writing system and the Efik orthography

The Efik Language is written using the Latin alphabet. The letters employed when writing the Efik Language include: a, b, d, e, f, g, i, k, m, n, ñ, o, ọ, s, t, u, w, y, kp, kw, ny, nw, gh.[46] The letters C, J, L, Q, V, X, and Z are not used.[47] For Q, the letter "Kw" and for the English 'ng' sound, the 'ñ' is used.[47] The consonant letters of the Efik language are divided into Single consant letters and double consonant letters.[46] The earliest orthography employed by the missionaries for the use of written Efik was developed by Dr Lepsius.[17] Goldie later developed a standard Efik orthography which was used until 1929.[48][49] Features of Goldie's orthography included, "Ö" which represented the IPA sound /ɔ/ found in words such as Law and Boy; n̄ was used to represent the "ng" consonant sounds. By 1929, the orthography was revised and the "Ö" alphabet was replaced with the inverted c i.e ɔ.[49] The n̄ consonant sound was also replaced with ŋ.[49] On 1 September 1975, a new Efik orthography was approved for use in schools by the Ministry of Education, Cross River state.[50] The ŋ consonant was replaced with n̂ and ɔ was replaced with ọ.[49] The following additional letters were also included to the 1975 revision i.e ẹ, ị, and ụ.[50]

| 1862–1929 | 1929–1975 | 1975–present |

|---|---|---|

| ö | ɔ | ọ |

| n̄ | ŋ | n̄ |

See also

References

- 1 2 Efik at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ↑ Bauer, p. 370

- ↑ Mensah and Ekawan, p.60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Simmons, p. 16

- ↑ Goldie, Dictionary of the Efik, p.28

- 1 2 Baikie, p.420

- ↑ Jeffreys, p.63

- ↑ Silverstein, p.211

- ↑ Goldie, Calabar, p.301

- 1 2 Greenberg, p.9

- ↑ DerHoussikian,p.320

- ↑ Faraclas, p.41

- 1 2 Robertson, p. 317

- 1 2 Forde, p. 8

- ↑ Williams, p. 541

- 1 2 3 Aye, A learner's Dictionary, p. xiii

- 1 2 "Welcome to Efik Eburutu of Nigeria". Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Aye, The Efik Language, p. 4

- ↑ Nair, p. 438

- ↑ Aye, Old Calabar, p. 154

- 1 2 Aye, The Efik Language, p. 5

- ↑ Offiong & Ansa, p. 25

- ↑ Jones-Jackson, p. 426

- ↑ Miller, p. 11

- 1 2 3 4 5 Essien, p. 15

- ↑ Ukpe, Queen Lucky (2018). Aspects of Èfîk Phonology. Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Calabar, Nigeria.

- ↑ Goldie, Principles, p. 5

- ↑ Ukpe, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Essien, p. 16

- ↑ Essien, p. 17

- 1 2 3 4 5 Essien, p. 19

- 1 2 3 Essien, p. 18

- ↑ Aye,A learner's Dictionary, p. x

- 1 2 Essien, p. 21

- ↑ Jeffreys, pp. 48-49

- ↑ Aye, A learner's dictionary, p. 71

- 1 2 Simmons, p. 17

- ↑ Simmons, p. 18

- 1 2 Simmons, p. 21

- ↑ Aye, A learner's dictionary, p. 114

- ↑ Ugot, p. 266

- ↑ Ugot, p. 29

- ↑ Nanji, p. 11

- 1 2 Nanji, p. 10

- ↑ "Angwatibo". Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- 1 2 Aye, A learner's Dictionary, p. iv

- 1 2 Una, p. 8

- ↑ Essien, p. 14

- 1 2 3 4 Essien, p. 20

- 1 2 Adams et al, p. xi

Bibliography

- Adams, R.F.G. (1952), English-Efik dictionary, Liverpool: Philip, Son & Nephew Ltd.

- Adams, R. F. G.; Akaduh, Etim; Abia-Bassey, Okon (1981), Akpanyụñ, Okon A. (ed.), English-Efịk dictionary, Oron: Manson Bookshop, OCLC 17150251

- Aye, Efiong U. (1967), Old Calabar through the centuries, Calabar: Hope Waddell Press, OCLC 476222042.

- Aye, Efiong U. (1985), The Efik Language and its future: A memorandum, Calabar: Glad Tidings Press Ltd., OCLC 36960798

- Aye, Efiong U. (1991), A learner's dictionary of the Efik Language, Volume 1, Ibadan: Evans Brothers Ltd, ISBN 9781675276

- Baikie, William Balfour (1856), Narrative of an Exploring Voyage up the Rivers Kwora and Binue (Commonly Known as the Niger and Tsadda) In 1854, London: John Murray: Albemarle Street, OCLC 3332112.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007), The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9780748631605

- Der-Houssikian, Haig (1972). "The Evidence for a Niger-Congo Hypothesis". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 12 (46): 316–322. doi:10.3406/cea.1972.2768. JSTOR 4391154. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- Essien, Okon Etim Akpan (1974). Pronominalisation in Efik (PhD). University of Edinburgh.

- Faraclas, Nicholas (1986). "Cross river as a model for the evolution of Benue-Congo nominal class/concord systems" (PDF). Studies in African Linguistics. 17 (1): 39–54. doi:10.32473/sal.v17i1.107495. S2CID 126381408.

- Goldie, Hugh (1862), Dictionary of the Efik Language, in two parts. I-Efik and English. II-English and Efik, Glassgow: Dunn and Wright

- Goldie, Hugh (1868), Principle of Efik Grammar with Specimen of the Language, Edinburgh: Muir & Paterson

- Goldie, Hugh (1890), Calabar and its Mission, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1963), The Languages of Africa, Bloomingtom, Indiana University

- Jeffreys, M.D.W. (1935), Old Calabar and notes on the Ibibio Language, Calabar: H.W.T.I. press

- Jones-Jackson, Patricia (1978). "Gullah: On the Question of Afro-American Language". Anthropological Linguistics. 20 (9): 422–429. JSTOR 30027488. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Mensah, Eyo; Ekawan, Silva (2016). "The Language of Libation Rituals among the Efik". Anthropological Notebooks. 22 (1): 59–76. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- Miller, Ivor (2009), Voice of the Leopard, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi

- Nair, Kannan K. (1973). "Reviewed Work: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE EFIK-IBIBIO-SPEAKING PEOPLES OF THE OLD CALABAR PROVINCE OF NIGERIA, 1668–1964 by A. N. Ekpiken". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 6 (4): 438–440. JSTOR 41856976. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Nanji, Cyril (2019), Balondo History and Customs, Buea: Bookman publishers, ISBN 9789956670185

- Robertson, G.A. (1819), Notes on Africa, London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, Paternoster Row, OCLC 7957153

- Silverstein, Raymond O. (1968). "A note on the term "Bantu" as first used by W. H. I. Bleek". African Studies. 27 (4): 211–212. doi:10.1080/00020186808707298.

- Simmons, Donald C. (1958). Analysis of the Reflection of Culture in Efik folktales (PhD). Yale University.

- Simmons, Donald C. (1968) [1st pub. 1956], "An Ethnographic Sketch of the Efik people", in Forde, Daryll (ed.), Efik Traders of Old Calabar, London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, OCLC 67514086

- Ugot, Mercy (2013). "Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Agwagune". African Research Review. 7 (3): 261–279. ISSN 2070-0083. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Ugot, Mercy (2010). "Language Choice, Code-switching and Code-mixing in Biase". Global Journal of Humanities. 8 (2): 27–35. ISSN 1118-0579. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Ukpe, Queen Lucky (2018). Aspects of Efik phonology (B.A). University of Calabar.

- Una, F.X. (2018), Efik Language, Uyo: Efik Leadership Foundation

- Williams, Gomer (1897), History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque: with an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade, London: William Heinemann; Edward Howell Church Street, OCLC 557806739