Indianapolis Union Station | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Union Station, 2022 | |||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||

| Location | 350 South Illinois Street Indianapolis, Indiana United States | ||||||||||

| Owned by | City of Indianapolis | ||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 island platform (formerly more) | ||||||||||

| Tracks | 2 (formerly 12) | ||||||||||

| Connections | |||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||

| Accessible | Yes | ||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||

| Station code | Amtrak: IND | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| Opened | September 20, 1853 | ||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1888, 1984, 2002 | ||||||||||

| Passengers | |||||||||||

| FY 2022 | 10,881[1] (Amtrak) | ||||||||||

| Services | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Indianapolis Union Railroad Station | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Location | 39 Jackson Place, Indianapolis | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°45′47″N 86°9′34″W / 39.76306°N 86.15944°W | ||||||||||

| Area | 1.3 acres (0.5 ha) | ||||||||||

| Built | 1886–1888 (head house); 1915–1922 (train shed) | ||||||||||

| Architect | Thomas Rodd | ||||||||||

| Architectural style | Richardsonian Romanesque | ||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 74000032[2] | ||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | July 19, 1974 | ||||||||||

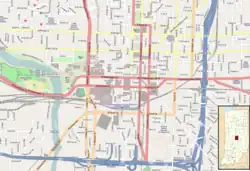

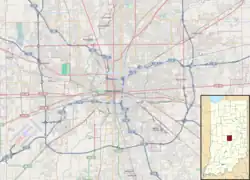

The Indianapolis Union Station is an intercity train station in the Wholesale District of Indianapolis, Indiana. The terminal is served by Amtrak's Cardinal line, passing through Indianapolis three times weekly.

Indianapolis was the first city in the world to devise a union station, in 1848. The station building opened on September 20, 1853, at 39 Jackson Place, operated by the Indianapolis Union Railway. A much larger Richardsonian Romanesque station was designed by Pittsburgh architect Thomas Rodd and constructed at the same location beginning in November 1886 and opening in September 1888. The head house (main waiting area and office) and clock tower of this second station still stand today.[3]

Amtrak, the national rail passenger carrier, continues to serve Union Station from a waiting area beneath the train shed. It is served by the Cardinal (Chicago–New York City, via Cincinnati and Washington, DC), and was the eastern terminus of the Hoosier State until its discontinuation on June 30, 2019.

Architecture

Thomas Rodd's design clearly shows the influence of architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886). Historian James R. Hetheringon has concluded that Pittsburgher Rodd would have studied the nearly completed Allegheny County Courthouse designed by Richardson prior to his death in 1886. Considered by Richardson to be his best work, the Courthouse was highly influential, with the Union Station one of the oldest surviving examples.[3][4][5][6]

The three-story Union Station is built of granite and brick trimmed with Hummelstown brownstone,[7] with a battered water table and massive brick arches characteristic of the Romanesque. It features an enormous rose window, slate roof, bartizans at section corners, and a soaring 185-foot (56 m) clock tower. The 1888 station included a large street-level iron train shed.[3][8][9]

History

Early history

The first railroad to reach Indianapolis was the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad, which began service there in 1847. Competing railroads began connecting Indianapolis to other locations, but each had its own station in various parts of the young city, creating problems for passengers and freight alike. This problem was common to many U.S. cities, but Indianapolis was the first to solve it with a union station, which all railroads were to use. In August 1849, the Union Railway Company was formed, and it began to lay tracks to connect the various railroads. Then in 1853, it built a large brick train shed at the point where all the lines met.[3] Between these dates, nearby Columbus, Ohio had built Columbus Union Station in 1851, becoming the first union station built. However, Indianapolis's station had more elements of a cooperative union station, especially as the Columbus station had one railroad lease space to another, while the Indianapolis station was a joint effort and ownership agreement.[10]

As Indianapolis and its railroad traffic grew, the limitations of the original structure became increasingly obvious. In 1886, Thomas Rodd was hired. At the time, Rodd was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad, but did independent civil engineering and architectural projects on the side. The new station was completed in 1888,[8] and during 1889 320,996 passenger train cars (across 45,204 trains) and 861,991 freight cars passed through the station.[11] In 1893, approximately 25,000 passengers rode an average of 120 passenger trains daily.[3][8]

By 1900, over 200 trains a day were being serviced, forcing the station to eventually build an expansive train shed on an elevated platform (built from 1915 to 1922[12]) so as not to interfere with regular street traffic. It was once second only to Chicago's Union Station as a Midwest railroad hub.[13]

After World War II

In the 1940s, several railroads still called at the station: the Baltimore & Ohio, the Chicago, Indianapolis and Louisville Railroad (Monon Railroad), the Illinois Central, the New York Central, the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad (Nickel Plate Road), and the Pennsylvania Railroad.[14] After World War II, intercity passenger rail travel in the United States began to decline.[8]

Passenger services, particularly named trains, at the union station included:[15]

| Operators | Named trains | Western or northern destination | Eastern or southern destination | Year discontinued |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amtrak | Cardinal | Chicago (Union Station) | New York, New York (Penn Station) | Still active |

| Hoosier State | Chicago | terminus | 2019 | |

| James Whitcomb Riley | Chicago | New York | 1974 | |

| Kentucky Cardinal | Chicago | Louisville, Kentucky (Union Station) | 2003 | |

| National Limited | Kansas City (Union Station) | New York | 1979 | |

| Floridian | Chicago (Union Station) | St. Petersburg or Miami | 1979 | |

| Monon Railroad | Hoosier | Chicago | terminus | 1959 |

| Tippecanoe | Chicago | terminus | 1959 | |

| New York Central | Corn Belt Special | Pekin, Illinois | terminus | 1957 |

| Southwestern Limited / Knickerbocker | St. Louis, Missouri (Union Station) | New York | 1967 | |

| Cincinnati Special / Sycamore | Chicago (La Salle Street) | Cincinnati, Ohio (Union Station) | 1967 | |

| Pennsylvania Railroad | Indianapolis Limited | terminus | New York (old Penn Station) | 1957 |

| Kentuckian | Chicago | Louisville (Union Station) | 1968 | |

| St. Louisan | St. Louis | New York | 1968 | |

| Pennsylvania Railroad, and Penn Central, 1967–1970 | Penn Texas | St. Louis | New York (new Penn Station) | 1970 |

| Pennsylvania Railroad, and Penn Central, 1967–1971 | South Wind | Chicago | St. Petersburg, Sarasota and Miami | 1971 |

| Spirit of St. Louis | St. Louis | New York | 1971 |

Decline

.jpg.webp)

Throughout the 1960s and well into the Amtrak era, the number of train passengers declined to such a trickle that, in cities in which rail stations did not serve commuter traffic, most were allowed to physically decline to a point where many were closed and some demolished. Indianapolis's Union Station almost suffered that fate. By the late 1970s, vagrants and vandals had taken over much of the facility and numerous police and fire runs were made to the cavernous building. Local business and political leaders began looking for some way to preserve Union Station and transform it into a vital part of the city again. Also in the 1970s, Amtrak planned to run its proposed AutoTrak service out of the Indianapolis Union Station, but this planned service was ultimately scrapped.[16]

In 1971, the city's mayor allocated $197,000 toward purchasing the building.[17]

The station was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 14, 1982.[2] Beginning in 1984, the facility was renovated and converted from its primary use as a railroad station to a festival marketplace. The Indianapolis architecture firm of Woollen, Molzan and Partners was responsible for the restoration of the station's historic shed, which reopened in 1986.[18] Union Station became a collection of restaurants, nightclubs, and specialty stores that included an NBC Store and a model train retailer. The eastern end of the former train platform area featured a large food court, plus several self-contained bars and nightclubs. Statues of individuals who might have been seen in the railroad station in prior years were installed throughout the facility. The 273-room Crowne Plaza Hotel took up much of the western portion of the train shed, with 26 of its rooms being housed within thirteen old Pullman cars.[19]

In 1997, the facility's marketplace era concluded with the departure of the last non-hotel and non-transportation tenant: a Hooters restaurant, which relocated to another nearby downtown building. The September 1995 opening of the Circle Centre Mall, just a block to the north, had drawn off the overwhelming majority of Union Station's retail customers. A planned pedestrian bridge between these two structures had been denied by officials for historic preservation reasons, and a direct underground connection was deemed to not be economically feasible. The city of Indianapolis was forced to take ownership of Union Station and began to try to find another reuse for much of the building. After some time, it began leasing out space for a wide variety of purposes, including office use and an indoor go-kart track.[20]

21st century

In 2002, the 21st Century Charter School was started within the facility. The still-successful hotel expanded to take up a larger portion of the building. Additional companies and organizations began to inquire about and lease space in the station. In 2006, tenants included Bands of America, the Consulate of Mexico (which has since relocated elsewhere downtown), the Indiana Museum of African American History, the Japan-America Society of Indiana, and the Indiana Pacers academy (another charter school). Many of the building's internal directories still display Spanish as well as English, reflecting the demographic changes in Indianapolis, as well as being a left over from the days when the building housed the Mexican Consulate. The Grand Hall of Union Station is also rented out for banquets and other special events.

In January 2011, a new underground walkway between the newly-expanded Indiana Convention Center (ICC) and nearby Lucas Oil Stadium opened. It also contains a connection to the Crowne Plaza hotel at the west end of Union Station. This climate-controlled pedestrian path replaces an above-ground link between the hotel and the now-demolished RCA Dome, which stood where the new wing of the convention center is now situated.

Passenger train service has been very limited in the Amtrak era. When Amtrak began operations in 1971, it ran three trains through Indianapolis–the South Wind, the James Whitcomb Riley, and the Spirit of St. Louis. However, most of these trains ran over deteriorating Penn Central trackage, and Amtrak eventually routed all of them away from Indianapolis except for the National Limited, successor of the Spirit of St. Louis.

Amtrak withdrew the National Limited in 1979, severing Indianapolis from the national rail network. It also isolated Amtrak's primary maintenance facility, the Beech Grove Shops in nearby Beech Grove. Rail service returned to Indianapolis in 1980, when the Hoosier State began running daily to Chicago. Northbound trains would leave in the morning, while southbound trains would arrive in the evening. It was joined in 1986 by the New York-to-Chicago Cardinal, successor of the James Whitcomb Riley. For most of the time from 1986 until Indiana withdrew its support for the train in June 2019, the Hoosier State ran on the four days that the Cardinal did not operate, thereby providing daily service along the route.

From 1999 to 2003, the station was served by the Kentucky Cardinal, an extension of the Hoosier State that ran to Louisville, operating as a section of the Cardinal on the days that the Cardinal ran. The southbound train split from the eastbound Cardinal at Union Station, while the northbound train joined the westbound Cardinal for the journey to Chicago. With the discontinuation of the Hoosier State, Indianapolis is served by only one train for only the second time in its history.

The station is served by two Amtrak Thruway lines–one serving western and central Illinois (the Quad Cities, Peoria, Bloomington-Normal, Champaign-Urbana, and Danville) and another that stops at Nashville, Louisville, and Cincinnati en route to Chicago.

Since 1979, Amtrak passengers use a waiting area in the southern portion of Union Station's old train shed, at street level along Illinois Street. The Amtrak station is co-located with the city's Greyhound bus depot, making this a multi-modal transportation hub, albeit a small one. As of January 2019, there is no commuter or light rail service in Indianapolis. The Greyhound ticket office is located along a wall opposite the Amtrak ticket office.

In FY 2013, Indianapolis averaged about 99 passengers daily, among the fewest for a station serving a metropolitan area of more than two million people. It is the busiest stop in Indiana served by Amtrak.

The 1888 station building is mostly leased for offices to pay for the building upkeep. The city struggled with finding a use for the building that is financially viable and high-profile. The Crowne Plaza Hotel still operates in the train shed structure, and leases out the main concourse, the Grand Hall, for weddings and other events.[19]

Gallery

North front, 1970

North front, 1970 Tower detail, 1970

Tower detail, 1970 South Illinois Street entrance

South Illinois Street entrance Train gates, 1970

Train gates, 1970 Main hall

Main hall Waiting room

Waiting room Platforms

Platforms

See also

References

- ↑ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2022: State of Indiana" (PDF). Amtrak. June 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- 1 2 "National Register Information System – (#74000032)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Indianapolis Union Railroad Station". Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ↑ Shank, Wesley (1970). "Union Station: Photographs and Written Historical and Descriptive Data". Historic American Buildings Survey. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. p. 2.

- ↑ Michael, Jesse (September 28, 2010). "The first 'union station' was a first (but the second was better)". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis: Gannett Co.

- ↑ Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1994). Architecture After Richardson: Regionalism before Modernism – Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow in Boston and Pittsburgh. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-226-25410-4.

- ↑ Advertising booklet published by the Hummelstown Brownstone Co., page 37, circa 1907

- 1 2 3 4 "Union Station: Once-bustling railroad station is one of Indianapolis' most cherished landmarks". Indianapolis Star. April 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved 2016-08-01. Note: This includes David R. Hermansen and Eric Gilbertsen (July 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Indianapolis Union Railroad Station" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-01., Site map, and Accompanying photographs

- ↑ Darbee, Jeffrey (2017). Indianapolis Union and Belt Railroads. Indiana University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780253029508. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ↑ Staff (1 February 1890). "Railway News". The Railroad Telegrapher. Peoria, Illinois. p. 20. Retrieved 2015-08-11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ 1935 Interstate Commerce Commission Valuation Report for Indianapolis Union Railway Company

- ↑ "Union Station". Emporis. 2004. Archived from the original on August 15, 2004. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ "Index of Railroad Stations". Official Guide of the Railways. National Railway Publication Company. 78 (12). May 1946.

- ↑ "Monon Railroad, New York Central, Pennsylvania Railroad". Official Guide of the Railways. National Railway Publication Company. 87 (7). December 1954.

- ↑ Sanders, Craig (2006). Amtrak in the Heartland. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253027931.

- ↑ Reusing Railroad Stations: Book Two. Educational Facilities Laboratories. September 1975. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ↑ Trounstine, Philip J. (May 9, 1976). "Evans Woollen: Struggles of a 'Good Architect'". [Indianapolis] Star Magazine. Indianapolis, Indiana: 23. See also: Mary Ellen Gadski, "Woollen, Molzan and Partners" in David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 1453–54. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- 1 2 Stall, Sam (March 22, 2016). "Who Killed Union Station?". Indianapolis Monthly. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ↑ "Union Station". indyencyclopedia.org. 2021-03-27. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

Further reading

- Powell, Eric (2016). "Indy's Union Station still dazzles". Classic Trains. 17 (1): 76–77.

External links

- Indianapolis – Amtrak

- Indianapolis – Station history at Great American Stations (Amtrak)

- Indianapolis Amtrak Station (USA Rail Guide -- Train Web)

- Rethinking Adaptive Reuse, or, How Not to Save a Great Urban Terminal by Erik Ledbetter

- Hetherington, James. "The History of Union Station" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- Indiana Historical Society page on Union Station

- Union Station from Indianapolis: a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary