Irish Republican Brotherhood Bráithreachas Phoblacht na hÉireann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 17 March 1858 |

| Dissolved | 1924 |

| Preceded by | Young Ireland |

| Newspaper | The Irish People |

| Ideology | Irish republicanism Irish nationalism |

| National affiliation | Irish Volunteers (1913–1917) Irish Republican Army (1917–1922) Irish National Army (1922–1924) |

| American affiliate | Fenian Brotherhood (1858–1867) Clan na Gael (1867–1924) |

| Colours | Green & Gold |

| Slogan | Erin go bragh |

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; Irish: Bráithreachas Phoblacht na hÉireann) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.[1] Its counterpart in the United States of America was initially the Fenian Brotherhood, but from the 1870s it was Clan na Gael. The members of both wings of the movement are often referred to as "Fenians". The IRB played an important role in the history of Ireland, as the chief advocate of republicanism during the campaign for Ireland's independence from the United Kingdom, successor to movements such as the United Irishmen of the 1790s and the Young Irelanders of the 1840s.

As part of the New Departure of the 1870s–80s, IRB members attempted to democratise the Home Rule League[2] and its successor, the Irish Parliamentary Party, as well as taking part in the Land War.[3] The IRB staged the Easter Rising in 1916, which led to the establishment of the first Dáil Éireann in 1919. The suppression of Dáil Éireann precipitated the Irish War of Independence and the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, ultimately leading to the establishment of the Irish Free State, which excluded the territory of Northern Ireland.

Background

In 1798 the United Irishmen, which had initially been an open political organisation, but which was later suppressed by the British establishment in Ireland and so became a secret revolutionary organisation, rose in rebellion, seeking an end to British rule in Ireland and the establishment of an Irish Republic. The rebellion was suppressed, but the principles of the United Irishmen were to have a powerful influence on the course of Irish history.

Following the collapse of the rebellion, the British prime minister William Pitt introduced a bill to abolish the Irish parliament and manufactured a Union between Ireland and Britain. Opposition from the Protestant oligarchy that controlled the parliament was countered by the widespread and open use of bribery.[4] The Act of Union was passed, and became law on 1 January 1801. The Catholics, who had been excluded from the Irish parliament, were promised emancipation under the Union. This promise was never kept, and caused a protracted and bitter struggle for civil liberties. It was not until 1829 that the British government reluctantly conceded Catholic emancipation. Though leading to general emancipation, this process simultaneously disenfranchised the small tenants, known as 'forty shilling freeholders', who were mainly Catholics.[5] This resulted in the Irish Catholic electorate going from 216,000 voters to 37,000. A massive reduction in the number of Catholics being able to vote.[6]

Daniel O’Connell, who had led the emancipation campaign, then attempted the same methods in his campaign, to have the Act of Union with Britain repealed. Despite the use of petitions and public meetings which attracted vast popular support, the government thought the Union was more important than Irish public opinion.

During the early 1840s, the younger members of the repeal movement became impatient with O’Connell's over-cautious policies, and began to question his intentions. Later they were what came to be known as the Young Ireland movement. In 1842 three of the Young Ireland leaders, Thomas Davis, Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon, launched the Nation newspaper. In the paper they set out to create a spirit of pride and an identity based on nationality rather than on social status or religion. Following the collapse of the Repeal Association and with the arrival of famine, the Young Irelanders broke away completely from O’Connell in 1846.[7]

The blight that destroyed the potato harvest between 1845 and 1850 caused a massive human tragedy. An entire social class of small farmers and labourers were to be virtually wiped out by hunger, disease and emigration. The laissez-faire economic thinking of the government ensured that help was slow, hesitant and insufficient. Between 1845 and 1851 the population fell by almost two million, or about a third of the total.

That the people starved while livestock and grain continued to be exported, quite often under military escort, left a legacy of bitterness and resentment among the survivors. The waves of emigration because of the famine and in the years following, also ensured that such feelings were not confined to Ireland, but spread to England, the United States, Australia, and every country where Irish emigrants gathered.[8]

Shocked by the scenes of starvation and greatly influenced by the revolutions then sweeping Europe, the Young Irelanders moved from agitation to armed rebellion in 1848. The attempted rebellion failed after a small skirmish in Ballingary, County Tipperary, coupled with a few minor incidents elsewhere. The reasons for the failure were obvious, the people were totally despondent after three years of famine, having been prompted to rise early resulted in an inadequacy of military preparations, which caused disunity among the leaders.

The government quickly rounded up many of the instigators. Those who could fled across the seas, and their followers dispersed. A last flicker of revolt in 1849, led by among others James Fintan Lalor, was equally unsuccessful.[9]

John Mitchel, the most committed advocate of revolution, had been arrested early in 1848 and transported to Australia on the purposefully created charge of Treason-felony. He was to be joined by other leaders, such as William Smith O'Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher who had both been arrested after Ballingary. John Blake Dillon escaped to France, as did three of the younger members, James Stephens, John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny.

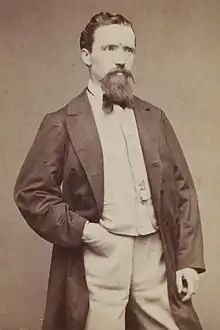

Founding of the IRB

After the collapse of the 1848 rebellion James Stephens and John O'Mahony went to Europe to avoid arrest. In Paris they supported themselves through teaching and translation work and planned the next stage of "the fight to overthrow British rule in Ireland."[10] Stephens set himself three tasks during his seven years of exile in Paris. These were: to keep alive, to pursue knowledge, and to master the technique of conspiracy. At this time Paris was interwoven with a network of secret political societies. Stephens and O'Mahony became members of one of the most powerful of these societies and acquired the secrets of some of the ablest and "most profound masters of revolutionary science" which the 19th century had produced, as to the means of inviting and combining people for the purposes of successful revolution.[11]

In 1853, O'Mahony went to America and founded the Emmet Monument Association.[12][13] In early 1856, Stephens began making his way back to Ireland, stopping first in London.[14] On arriving in Dublin, Stephens began what he described as his three thousand mile walk through Ireland, meeting some of those who had taken part in the 1848/49 revolutionary movements, including Philip Gray, Thomas Clarke Luby and Peter Langan.[15] In the autumn of 1857, a messenger, Owen Considine arrived from New York with a message for Stephens from members[16] of the Emmet Monument Association, calling on him to set up an organisation in Ireland. Considine also carried a private letter from O’Mahony to Stephens which was a warning as to the condition of the organisation in New York, which was overseen by Luby and Stephens at the time. Both had believed that there was a strong organisation behind the letter, only later to find it was a number of loosely linked groups.[17]

On 23 December Stephens dispatched Joseph Denieffe to America with his reply which was disguised as a business letter, and dated and addressed from Paris. In his reply Stephens outlined his conditions and his requirements from the organisation in America.[18] Stephens demanded uncontrolled power and £100 a month for the first three months.[19] Denieffe returned on 17 March 1858 with the acceptance of Stephens terms and £80. Denieffe also reported that there was no actual organised body of sympathisers in New York but merely a loose knot of associates. This disturbed Stephens but he went ahead regardless and that evening, St. Patrick's Day, the Irish Republican Brotherhood commenced.[20][21]

The original oath, with its clauses of secrecy was drawn up by Luby under Stephens' direction in Stephens' room in Donnelly's which was situated behind Lombard Street. Luby then swore Stephens in and he did likewise.

Those present in Langan's, lathe-maker and timber merchant, 16 Lombard Street for that first meeting apart from Stephens and Luby were Peter Langan, Charles Kickham, Joseph Denieffe[22] and Garrett O'Shaughnessy.[23][24] Later it would include members of the Phoenix National and Literary Society, which was formed in 1856 by Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa in Skibbereen.[25]

Organisational structure

The IRB was organised into circles, a "circle" was analogous to a regiment, that the "centre" or A, who might be considered equivalent to a colonel, who chose nine B's, or captains, who in their turn chose nine C's, or sergeants, who in their turn chose nine D's, who constituted the rank and file. In theory an A should only be known to the B's; a B, to his C's: and a C, to his D's; but this rule was often violated.[25]

Objectives

.png.webp)

Dublin Castle was the seat of government administration in Ireland and was appointed by the British cabinet and was accountable only to the cabinet, not to the House of Commons and not to the Irish people or their political representatives. Irish MPs could speak at Westminster in protest about the actions of the administration, but its privileges were unchallengeable as Irish representation in the House of Commons was only one sixth of the total and far too small.[26]

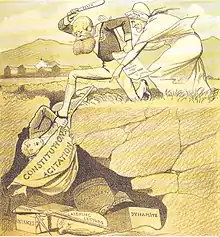

Fenianism therefore, according to O'Mahony was symbolised by two principles: Firstly, that Ireland had a natural right to independence, and secondly, that that right could be won only by an armed revolution.[27] Because of their belief in republicanism, that is, the "common people are the rightful rulers of their own destiny", the founding members saw themselves as "furious democrats in theory" and declared their movement to be "wholly and unequivocally democratic".[28] Being a democrat and egalitarian in the mid 19th century was tantamount to being a revolutionary, and was something to be feared by political establishments.[29]

It was Stephens "firm resolution to establish a democratic republic in Ireland; that is, a republic for the weal of the toiler",[30] and that this would require a complete social revolution before the people could possibly become republicans.[1] In propagating republican principles, they felt, the organisation would create this virtual democracy within the country, which would form the basis of an independence movement.[31]

The Fenians soon established themselves in Australia, South America, Canada and, above all, in the United States, as well as in the large cities of England, such as London, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow, in Scotland.

The oath

| Part of a series on |

| Irish republicanism |

|---|

|

The original IRB oath, as quoted by Thomas Clarke Luby and John O'Leary, and which is among several versions in James Stephens's own papers, ran:

I, AB., do solemnly swear, in the presence of Almighty God, that I will do my utmost, at every risk, while life lasts, to make [other versions, according to Luby, 'establish in'] Ireland an independent Democratic Republic; that I will yield implicit obedience, in all things not contrary to the law of God ['laws of morality'] to the commands of my superior officers; and that I shall preserve inviolable secrecy regarding all the transactions [ 'affairs'] of this secret society that may be confided in me. So help me God! Amen.[32]

This oath was significantly revised by Stephens in Paris in the summer of 1859. He asked Luby to draw up a new text, omitting the secrecy clause. The omitting of the secrecy clause was outlined in a letter from Stephens to John O'Mahony on 6 April 1859 and the reasons for it.[33] 'Henceforth,’ wrote Luby to O’Leary "we denied that we were technically a secret body. We called ourselves a military organization; with, so to speak, a legionary oath like all soldiers."[34]

The revised oath ran:

I, A.B, in the presence of Almighty God, do solemnly swear allegiance to the Irish Republic, now virtually established; and that I will do my very utmost, at every risk, while life lasts, to defend its independence and integrity; and, finally, that I will yield implicit obedience in all things, not contrary to the laws of God [or 'the laws of morality'], to the commands of my superior officers. So help me God. Amen'.[35]

In yet a later version it read:

In the presence of God, I, ..., do solemnly swear that I will do my utmost to establish the independence of Ireland, and that I will bear true allegiance to the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Government of the Irish Republic and implicitly obey the constitution of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and all my superior officers and that I will preserve inviolable the secrets of the organisation.[36]

Supreme Council

The IRB was re-organised at a convention in Manchester in July 1867. An 11-man Supreme Council was elected to govern the movement.[37] They would eventually be representatives from the seven districts in which the organisation was organised: the Irish provinces of Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht, as well as Scotland, North England, and South England. The remaining four members were co-opted. The Supreme Council elected three of its members to the executive, which consisted of a president, secretary, and a treasurer. The Council met twice a year, usually in the spring and the summer. In Manchester August 1867 Thomas Kelly was declared Chief Organiser of the Irish Republic (COIR), in succession to Stephens. The arrest and subsequent rescue of Kelly with Timothy Deasy in September 1867 resulted in the execution of the Manchester Martyrs. Kelly escaped to USA and remained associated with the IRB.

United States organisation

Late in 1858 Stephens travelled to the United States to secure support and financial backing. He was unsuccessful, however, in winning the support of former Young Irelanders such as John Mitchel and Thomas Francis Meagher. Eventually, he joined with John O'Mahoney and Michael Doheny to form the Fenian Brotherhood, intended as the American sister organisation of the IRB, with O'Mahoney as its president. The precise relationship between the two organisations was never properly set out.[38] In the early 1870s the Fenian Brotherhood was superseded as the main American support organisation by Clan na Gael, of which John Devoy was a leading member. The IRB and Clan na Gael reached a "compact of agreement" in 1875, and in 1877 the two organisations established a joint "revolutionary directory". This effectively gave Devoy control over the Supreme Council in Ireland, which was reliant on Clan na Gael for funds.[39]

Nineteenth century

Establishment reaction

The movement was denounced by the British establishment, the press, the Catholic Church and Irish political elite, as had been all Irish Republican movements at that point.[40]

The Tories, disturbed by the increase in republican propaganda, particularly in America, launched a propaganda campaign in the Irish press to discredit the American Fenians. They presented them as enemies of Catholicism quoting negative comments by some American Catholic bishops. As in Irish-America, likewise Ireland and England, the Catholic hierarchy felt the growth of nationalist politics among Irishmen was essentially dangerous. Therefore, during the 1860s and succeeding decades, the upper or middle classes who controlled the Irish press were very apprehensive in the growth of democratic politics in Ireland, which represented to them a threat of anarchy and revolution.[41]

It was feared that if Britain was given any reason to renew coercion, Catholic interests in both Ireland and England would be undermined. In addition, the small class of Irish Catholic merchants, lawyers and gentry who had prospered under the Union felt anxious for the same reasons. By 1864, the Tories had coined the phrase 'Fenianism' to describe all that was considered potentially bothersome among Irishmen on both sides of the Atlantic.[41]

Fenianism as a term was then used by the British political establishment to depict any form of mobilisation among the lower classes and, sometimes, those who expressed any Irish nationalist sentiments. They warned people about this threat to turn decent civilised society on its head such as that posed by trade unionism to the existing social order in England.[42] The same term was taken up by members of the Irish Catholic hierarchy, who also began denouncing "Fenianism" in the name of the Catholic religion.[41] One Irish Bishop, David Moriarty of Kerry, declared that "when we look down into the fathomless depth of this infamy of the heads of the Fenian conspiracy, we must acknowledge that eternity is not long enough, nor hell hot enough to punish such miscreants."[43][44]

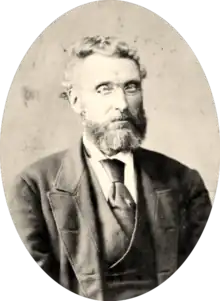

Irish People

In mid-1863 Stephens informed his colleagues he wished to start a newspaper, with financial aid from O’Mahony and the Fenian Brotherhood in America. The offices were established at 12 Parliament Street, almost at the gates of Dublin Castle.[45] The first edition of the Irish People appeared on 28 November 1863.[46] The staff of the paper along with Kickham were Luby and Denis Dowling Mulcahy as the editorial staff. O’Donovan Rossa and James O’Connor were in charge of the business office, with John Haltigan being the printer. John O'Leary was brought from London to take charge in the role of Editor.[47] Shortly after the establishment of the paper, Stephens departed on an American tour, and to attend to organisational matters.[48]

American Fenians made plans for a rising in Ireland, but the plans were discovered on 15 July 1865 when an emissary lost them at Kingstown railway station. They found their way to Dublin Castle and to Superintendent Daniel Ryan head of G Division. Ryan had an informer within the offices of the Irish People named Pierce Nagle, he supplied Ryan with an "action this year" message on its way to the IRB unit in Tipperary. With this information, Ryan raided the offices of the Irish People on Thursday 15 September, followed by the arrests of O’Leary, Luby and O’Donovan Rossa. The last edition of the paper is dated 16 September 1865.[49]

Arrests and escapes

Before leaving, Stephens entrusted to Luby a document containing secret resolutions on the Committee of Organization or Executive of the IRB. Though Luby intimated its existence to O’Leary, he did not inform Kickham as there seemed no necessity. This document would later form the basis of the prosecution against the staff of the Irish People. The document read:[50]

EXECUTIVE

I hereby appoint Thomas Clarke Luby, John O’Leary and Charles J. Kickham, a Committee of Organization or Executive, with the same supreme control over the Home Organization (Ireland, England, Scotland, etc.) I have exercised myself. I further empower them to appoint a Committee of Military Inspection, and a Committee of Appeal and Judgment, the functions of which Committee will be made known to each member of them by the Executive.

Trusting to the patriotism and ability of the Executive, I fully endorse their action beforehand, and call on every man in our ranks to support and be guided by them in all that concerns our military brotherhood.

9 March 1864, Dublin

J. STEPHENS

Kickham was caught after a month on the run.[51] Stephens would also be caught, but with the support of Fenian prison warders, John J. Breslin[52] and Daniel Byrne was less than a fortnight in Richmond Bridewell when he vanished and escaped to France.[53] David Bell evaded arrest, escaping first to Paris and then to New York[54]

Fenian Rising

During the latter part of 1866, Stephens endeavoured to raise funds in America for a fresh rising planned for the following year. He issued a bombastic proclamation in America announcing an imminent general rising in Ireland; but he was himself soon afterwards deposed by his confederates, among whom dissension had broken out.

The Fenian Rising proved to be a "doomed rebellion", poorly organised and with minimal public support. Most of the Irish-American officers who landed at Cork, in the expectation of commanding an army against England, were imprisoned; sporadic disturbances around the country were easily suppressed by the police, army and local militias.

Manchester Martyrs and Clerkenwell explosion

On 22 November 1867 three Fenians, William Philip Allen, Michael O'Brien, and Michael Larkin known as the Manchester Martyrs, were executed in Salford for their attack on a police van to release Fenians held captive earlier that year.

On 13 December 1867 the Fenians exploded a bomb in attempt to free one of their members being held on remand at Clerkenwell Prison in London. The explosion damaged nearby houses, killed 12 people and caused 120 injuries. None of the prisoners escaped. The bombing was later described as the most infamous action carried out by the Fenians in Great Britain in the 19th century. It enraged the public, causing a backlash of hostility in Britain which undermined efforts to establish home rule or independence for Ireland.

Irish National Invincibles

In 1882, a breakaway IRB faction calling itself the Irish National Invincibles assassinated the British Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish and his secretary, in an incident known as the Phoenix Park Murders.

Special Irish Branch

In March 1883 the Metropolitan Police's Special Irish Branch was formed, initially as a small section of the Criminal Investigation Department, to monitor IRB activity.

Twentieth century

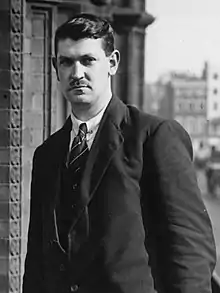

By the start of the 20th century, the IRB was a stagnating organisation, concerned more with Dublin municipal politics than the establishment of a republic, according to F. S. L. Lyons.[55] A younger generation of Ulster republicans aimed to change this, and in 1905 Denis McCullough and Bulmer Hobson founded the Dungannon Clubs. Inspired by the Volunteers of 1782, the purpose of these clubs was to discourage enlistment into the British Army, and encourage enlistment into the IRB, with the overall goal of complete independence from Britain in the form of an Irish Republic.[56] They were joined by Seán Mac Diarmada, and in 1908 he and Hobson relocated to Dublin, where they teamed up with veteran Fenian Tom Clarke. Clarke had been released from Portland Prison in October 1898 after serving fifteen and a half years, and had recently returned to Ireland after living in the United States.[57] Sent by John Devoy and the Clan na Gael to reorganise the IRB, Clarke set about to do just that.[58] In 1909 the young Michael Collins was introduced to the brotherhood by Sam Maguire. By 1914 the Supreme Council was largely purged of its older, tired leadership, and was dominated by enthusiastic men such as Hobson, McCullough, Patrick McCartan, John MacBride, Seán Mac Diarmada, and Tom Clarke.[59] The latter two were to be the primary instigators of the Easter Rising in 1916.

Easter Rising

Following the establishment of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, whose purpose was to resist Home Rule, by force if necessary, the IRB were behind the initiative which eventually led to the inauguration of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913.[60] Though the Volunteers' stated purpose was not the establishment of a republic, the IRB intended to use the organisation to do just that, recruiting high-ranking members into the IRB, notably Joseph Plunkett, Thomas MacDonagh, and Patrick Pearse, who was co-opted to the Supreme Council in 1915. These men, together with Clarke, MacDermott, Éamonn Ceannt and eventually James Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army, constituted the Military Committee, the sole planners of the Rising.

War of Independence, Civil War and dissolution

Following the Rising some republicans—notably Éamon de Valera and Cathal Brugha—left the organization, which they viewed as no longer necessary, since the Irish Volunteers now performed its function.[61] The IRB, during the 1919–21 War of Independence, was under the control of Michael Collins, who was secretary, and subsequently president, of the Supreme Council.[61] Volunteers such as Séumas Robinson said afterwards that the IRB by then was "moribund where not already dead", but there is evidence that it was an important force during the war.[61]

When the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921, it was debated by the Supreme Council, which voted to accept it by eleven votes to four.[62] Those on the Supreme Council who opposed the Treaty included former leader Harry Boland, Austin Stack and Liam Lynch.[63] Anti-Treaty republicans like Ernie O'Malley, who fought during the Civil War against the Treaty, saw the IRB as being used to undermine the Irish Republic.[64] The IRB became quiescent during the Civil War, which ended in May 1923, but it emerged again later that year as a faction within the National Army that supported Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy against the "Old IRA", which fought against the recruitment of ex-British Army personnel and the demobilization of old IRA men.[65] This came to a head with the Army Mutiny of 1924, in the wake of which Mulcahy resigned and other IRB members of the army were dismissed by acting President of the Executive Council Kevin O'Higgins.[66] The IRB subsequently dissolved itself, although it is not known whether a formal decision was taken, or it simply ceased to function.[67]

Presidents

What follows is a list of known IRB presidents. As no formal records exist for the IRB, accurate dates cannot be provided in all cases.

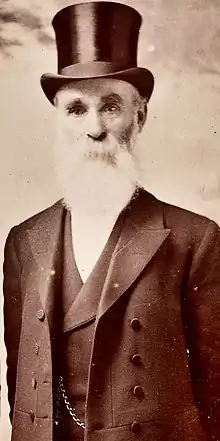

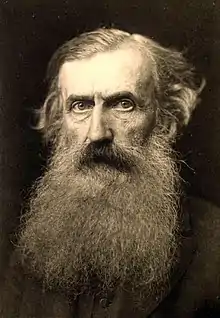

| No. | Image | Name | Assumed office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | James Stephens | 17 March 1858 | December 1866 | |

| 2. | Thomas J. Kelly | August 1866 | c. 1869 | |

| 3. | J. F. X. O'Brien | c. 1869 | c. 1872 | |

| 4. | Charles Kickham | 15 January 1873 | 22 August 1882 | |

| 5. | John O'Connor Power | 1882 | 1891 | |

| 6. | John O'Leary | 1891 | 16 March 1907 | |

| 7. | Neal O'Boyle | 1907 | 1910 | |

| 8. | John Mulholland | 1910 | 1912 | |

| 9. | Seamus Deakin | 1913 | 1914 | |

| 10. | Denis McCullough | 1915 | 1916 | |

| 11. | Thomas Ashe | 1916 | 1917 | |

| 12. | Seán McGarry | November 1917 | May 1919 | |

| 13. | Harry Boland | May 1919 | September 1920 | |

| 14. | Patrick Moylett | September 1920 | November 1920 | |

| 15. | Michael Collins | November 1920 | August 1922 | |

| 16. | Richard Mulcahy | August 1922 | 1924 |

See also

- Catalpa rescue, the escape of six Fenians from Western Australia

- John Boyle O'Reilly, Fenian who escaped from Western Australia in 1869

- Land and Liberty (Russia) – 1860s and 1870s Russian Narodnik revolutionary organization

- Secret society

References

- 1 2 McGee, p. 15.

- ↑ In November 1873, the Home Government Association was reconstituted as the Home Rule League. As with the HGA, Butt was opposed to its membership having any power to dictate policy (cite, McGee, p. 47.). The Irish MPs at Westminster "felt total contempt" for the idea of promoting a radical "democratic movement" in Ireland (Ibid, p. 53.). Charles Doran secretary of the Supreme Council of the IRB, proposed that all MP's should be accountable before "a great national conference ... as to represent the opinions and feelings of the Irish nation" (Ibid, p. 48.).

- ↑ McGee, pp. 46–60.

- ↑ In Search of Ireland's Heroes: Carmel McCaffrey p. 146

- ↑ Kenny, p. 5.

- ↑ In Search of Ireland's Heroes: Carmel McCaffrey p. 156

- ↑ Kenny, p. 6.

- ↑ Kenny, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Kenny, p. 7.

- ↑ Ó Broin, p. 1

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, pp. 43 & 48.

- ↑ According to tradition, no monument can be erected to Robert Emmet "until Ireland a nation can build him a tomb," therefore, the work of the Association presupposed the freedom of Ireland as a necessary preliminary.

- ↑ Denieffe, vii

- ↑ While in London, Stephens had doubts as to whether Ireland was yet ripe for his plans. He posed himself two questions, and only in Ireland could he obtain the answers, the first being: was a new uprising even conceivable and had the time come for a secret revolutionary organisation under his leadership. cite O'Leary pp. 57–8.

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, p. 58.

- ↑ the name of the members were John O'Mahony, Michael Doheny, James Roche and Oliver Byrne. cite O'Leary, p. 80.

- ↑ Ryan Desmond, p. 87.

- ↑ A full copy of the letter is available in Desmond Ryan's Fenian Chief pp. 89–90.

- ↑ O'Leary p. 82.

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, pp. 90–91, Ó Broin, p. 1, Cronin, p. 11.

- ↑ It has been suggested, notably by O'Donovan Rossa, that the original name for the organisation was the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, this is a view shared by Joseph Denieffe in his memoirs. It also appears in correspondences of the Fenian Leaders, Devoy's Post Bag being another example. What is certain is that it became the Irish Republican Brotherhood and it lasted in Ireland and among Irish exiles all over the world under that name.

- ↑ In John O'leary's Fenians and Fenianism, he spells the name "Deneefe" though this is incorrect, cite O'Leary, p. 82.

- ↑ O'Leary, p. 82.

- ↑ An Phoblacht 13 March 2008

- 1 2 O'Leary, p. 84.

- ↑ McGee, p. 21.

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, p. 318.

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, p. 326, also cited by McGee, p. 16.

- ↑ McGee, p. 16.

- ↑ Ryan. Desmond, p. 133.

- ↑ McGee, p. 327.

- ↑ O’Leary, p. 82.

- ↑ ... The form of the test, I leave to yourself, merely telling you that the oath of secrecy must be omitted. The clause, however, which binds them to "yield implicit obedience to the commands of superior officers" provides against their babbling propensities, for, when the test in its modified form is administered, you, as the superior official, in the case of the men you enroll, command them to be silent with regard to the affairs of the brotherhood, and to give the same command to the men of the grade below them, and so on. But the test, in its modified form, is not to be administered to any one who considers it a cause of confession...." Rossa, p. 279.

- ↑ Ryan Desmond, p. 91.

- ↑ Authors brackets, Ryan. Desmond, p. 92.

- ↑ "Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough" (PDF). The 1916 Rising: Personalities and Perspectives. National Library of Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 14.

- ↑ Comerford, R. V. (1989). "Conspiring Brotherhoods and Contending Elites". In Vaughan, W. E. (ed.). " A New History of Ireland V: Ireland under the Union 1801-70. Oxford University Press. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-19-821743-5. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ↑ Comerford, R. V. (1989). "The Land War and the Politics of Distress, 1877–82". In Vaughan, W. E. (ed.). A New History of Ireland VI: Ireland under the Union 1870–1921. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-19-821751-0. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ↑ McGee, pp. 328–9.

- 1 2 3 McGee, p. 33.

- ↑ McGee, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Irish Times, 19 February 1867.

- ↑ Leon Ó Broin, p. 133.

- ↑ D. Ryan, pp. 187–90

- ↑ O'Leary Vol I, p. 246.

- ↑ Denieffe, p. 82.

- ↑ D. Ryan, p. 191.

- ↑ O’Leary, Vol II, p. 198.

- ↑ D. Ryan, p. 195.

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 58–9.

- ↑ Breslin would go on to play a leading part in the Catalpa rescue of Fenian prisoners in the British penal colony of Western Australia

- ↑ Ó Broin, pp. 26–7.

- ↑ Bell, Thomas (1967). "The Reverend David Bell". Clogher Historical Society. 6 (2): 253–276. doi:10.2307/27695597. JSTOR 27695597. S2CID 165479361. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Lyons, p. 315

- ↑ Lyons, p. 316.

- ↑ Clarke K. p. 24 & 36

- ↑ Charles Townshend, Easter 1916: The Irish rebellion, 2005, p. 18; Sean Cronin, The McGarrity Papers: revelations of the Irish revolutionary movement in Ireland and America 1900–1940, 1972, pp. 16, 30; Patrick Bishop & Eamonn Mallie, The Provisional IRA, 1988, p. 23; J Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army: The IRA, rev. ed., 1997, p. 9; Tim Pat Coogan, The IRA, 1984, p. 31

- ↑ Lyons, pp. 318–319

- ↑ Charles Townshend, Easter 1916: The Irish rebellion, 2005; p. 41, Tim Pat Coogan, The IRA, 1970, p. 33; F. X. Martin, The Irish Volunteers 1913–1915, 1963, p. 24, Michael Foy & Brian Barton, The Easter Rising, 2004, p. 7, Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, 2007, p. 79, P. S. O’Hegarty, Victory of Sinn Féin, pp. 9–10; Michael Collins, The Path to Freedom, 1922, p. 54; Sean Cronin, Irish Nationalism, 1981, p. 105; P. S. O’Hegarty, A History of Ireland Under the Union, p. 669; Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: Easter Rising, p. 50; Kathleen Clarke, Revolutionary Woman, 1991, p. 44; Robert Kee, The Bold Fenian Men, 1976, p. 203, Owen McGee, The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from the League to Sinn Féin, 2005, pp. 353–354.

- 1 2 3 Murray, Daniel (11 November 2013). "To Not Fade Away: The Irish Republican Brotherhood Post-1916". The Irish Story. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Ó Broin, Leon (1976). Revolutionary underground: The Story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. pp. 195–6. ISBN 9780717107780. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Ó Broin (1976), p. 199

- ↑ In his book The Singing Flame (pp. 36-7), O'Malley, who was not an IRB member, describes attending an IRB meeting in Limerick in 1922, in which members were ordered to accept the Treaty. He viewed this as an attempt to manipulate the IRA by a secret oath-bound organisation.

- ↑ Lee, Joseph (1989). Ireland, 1912-1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0521377412. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Bell, J. Bowyer (1997). The Secret Army: The IRA. Transaction Publishers. p. 46. ISBN 1412838886. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Ó Broin (1976), p. 221

Bibliography

- "Irish Republican Brotherhood : 150th Anniversary". An Phoblacht. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 30 May 2008.

- Campbell, Christy, Fenian Fire: The British Government Plot to Assassinate Queen Victoria, HarperCollins, London, 2002, ISBN 0-00-710483-9

- Clarke, Kathleen, Revolutionary Woman: My Fight for Ireland's Freedom, O'Brien Press, Dublin, 1997, ISBN 0-86278-245-7

- Comerford, R.V., The Fenians in Context, Irish Politics and Society, 1848–82, Dublin, 1885

- Cronin, Sean, The McGarrity Papers, Anvil Books, Ireland, 1972

- Denieffe, Joseph, A Personal Narrative of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, The Gael Publishing Co, 1906

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- Irish Times

- Kelly, M. J., The Fenian Ideal and Irish Nationalism, 1882–1916, Boydell, 2006. ISBN 1-84383-445-6

- Kenny, Michael, The Fenians, The National Museum of Ireland in association with Country House, Dublin, 1994, ISBN 0-946172-42-0

- Lyons, F. S. L., Ireland Since the Famine, Fontana, 1973

- McGee, Owen, The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from The Land League to Sinn Féin, Four Courts Press, 2005, ISBN 1-85182-972-5

- Moody, T.W. and Leon O'Broin, eds., 'The IRB Supreme Council, 1868–78', Irish Historical Studies, xix, no. 75 (March 1975), 286–332.

- Ó Broin, Leon, Fenian Fever: An Anglo-American Dilemma, Chatto & Windus, London, 1971, ISBN 0-7011-1749-4.

- O'Donovan Rossa, Jeremiah, Rossa's Recollections, 1838 to 1898 Mariner"s Harbor, NY, 1898

- O'Leary, John, Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism, Downey & Co, Ltd, London, 1896 (Vol. I & II)

- Ryan, Desmond, The Fenian Chief: A Biography of James Stephens, Gill & Son, Dublin, 1967

- Ryan, Dr. Mark F., Fenian Memories, Edited by T. F. O'Sullivan, M. H. Gill & Son, LTD, Dublin, 1945

- Stanford, Jane, That Irishman: The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power, The History Press, Ireland, May 2011, ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1

- Whelehan, Niall, The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, Cambridge, 2012. ISBN 978-1-107-02332-1

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)