Irish in the British Armed Forces refers to the history of Irish people serving in the British Armed Forces (including the British Army, the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and other elements). Ireland was then as part of the United Kingdom from 1800 to 1922 and during this time in particular many Irishmen fought in the British Army. Different social classes joined the military for various reasons, including the Anglo-Irish officers who thoroughly wished to support the "mother country", while others, typically poorer Irish Catholics, did so to support their families or seeking adventure.

Many Irishmen and members of the Irish diaspora in Britain and also Ulster-Scots served in both World War I and World War II as part of the British forces. However, since the advent of Irish independence and The Troubles, the topic of enlistment in the British forces has been controversial for the Irish at home, but does still occur. Since partition, Irish citizens have continued to have the right to serve in the British Army, reaching its highest levels since World War II in the 1940s.[1]

History

Background and earlier contacts

Gaelic kerns fighting under the Normans

As far back as the High Middle Ages, following the Norman invasion of Ireland, some Gaels acted as mercenary ceithearnach recruited by Anglo-Norman lords to fight in their various feudal campaigns. As various different forces grappled for control of land, some of the Gaelic factions joined with some of the Norman factions fighting side by side, either out of ad hoc self-interest or as a mercenary action. As part of this they fought not only in Ireland, but also in England during the Wars of the Roses and in France during the Hundred Years' War. In his work on the Hundred Years' War, Desmond Seward mentions that the Earl of Ormond had raised Irish kern and Gallowglass to fight for Henry V Plantagenet, King of England, where they were present at the 1418 Siege of Rouen.

During this time, with the exception of the Pale, much of Ireland was outside of the English Crown's direct control, but because of the close location to the Kingdom of England, whichever faction in the Wars of the Roses was currently out of favour; Yorkist or Lancastrian; could find refuge in Ireland, often attempting to raise an armed force. Only one full-scale battle took place in Ireland itself, between Yorkists (FitzGeralds) and Lancastrians (Butlers) at the Battle of Piltown in 1462, where Irish troops fought on both sides. This was part of the Butler–FitzGerald dispute between two of the leading Anglo-Norman families in Ireland. The most notable instance from this period is from the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487. This was as part of the Lambert Simnel campaign, where the leading Yorkist figure the Earl of Lincoln was able to rise 5,000 Irish kerns, through his contacts with the FitzGerald family.

Tudor military involvement with Ireland

The Tudor-era saw a new stage of military development in Ireland with the creation of the Kingdom of Ireland. Figures such as Anthony St. Leger and Thomas Wolsey, as well as Henry VIII Tudor himself, favoured an assimilationist policy for Ireland of surrender and regrant, whereby the Gaelic Irish leaders would be brought into alliance with the English Crown, securing their lands on the condition of abandoning their customs.[2] There was no standing army and so during this early period of Tudor Ireland, commissions and military matters were under the administration of a local county High Sheriff (often of Gaelic Irish or Old English stock). A harsher and more aggressive policy under his offspring—Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I—whereby martial law would be implemented and New English settlers brought into the country to administrate military matters, made participation with crown forces more disreputable.[2]

Pre-emptive martial law was introduced by Lord Deputy, the Earl of Sussex in 1556, during the reign of Mary Tudor, while she was colonising the lands of the Ó Mórdha as "Queen's County" and the Ó Conchubhair Fáilghe as "King's County".[2] This allowed for persons suspected of oppositionist tendencies to be executed without trial, as well as against "tax offenders" and the displaced poor. This continued on during the Elizabethan period, with Henry Sidney and William FitzWilliam following suit. Many of the local Gaelic Irish and Old English were displaced from positions of power and previously friendly persons such as James FitzMaurice FitzGerald and Fiach Mac Aodha Ó Broin rose up in military revolt. Massacres by English forces, such as Rathlin, Clandeboye and Mullaghmast also turned the Irish against trusting the Crown and led to the development of a proto-Irish nationalism. Eventually, by 1585, Elizabeth had been advised to abandon martial law by the Earl of Ormond, Archbishop Adam Loftus and Sir Nicholas White.[2] The works of Richard Beacon and Edmund Spenser encouraged the return of a harsher repression and following this threat, some Gaels such as Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill and Aodh Mór Ó Néill joined rank militarily with Catholic Spain against the Protestant Tudor forces.[2]

Stuart military involvement with Ireland

With the Christian sectarian division now a permanent fixture of Irish society, the Stuart period would see more religion-associated conflicts. Due to the English having financial problems, James I Stuart offered a pardon to the participants of Tyrone's Rebellion along the lines of surrender and regrant in 1603, but neither side fully trusted the other. These leaders of Ulster Gaeldom fled with the Flight of the Earls in 1607 in the hopes of militarily retaking their lands with the assistance of Spain (a goal which had little practical chance of success, due to the Treaty of London). A year later, Sir Cathaoir Ó Dochartaigh, a previous supporter of the English forces against Ó Néill, rose up due to ill-treatment and goading at the hands of George Paulet with O'Doherty's Rebellion. After the rebellion failed, in the same year, James I instigated the Plantation of Ulster, bringing in Scottish and English Protestants to be settled on confiscated Gaelic lands. Irish Catholics were extremely hostile to the plantations and the confiscation of their land it entailed; bardic poets such as Lochlann Óg Ó Dálaigh captured the popular sentiment towards them in a poem: "Where have the Gaels gone? We have in their stead an arrogant, impure crowd of foreigners' blood. There are Saxons there and Scotch."[3]

Ireland would have a significant role to play in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Throughout the realms under the Stuart monarchy, sectarian tensions bubbled away as the Crown attempted to erect Episcopalianism as the state religion. For Ireland, the tensions were doubled due to the specter of land-dispossession (continued under the Earl of Stafford) and the push to Anglicisation. Irish Catholics pressed for civil liberties known as The Graces: Stafford said they would be delivered if the Irish helped to suppress the Covenanters in Scotland during the Bishops Wars (enraging the English and Scottish Parliaments). The situation came to ahead when the Irish Catholic gentry under Féilim Ó Néill attempted a desperate coup d'état with the Irish Rebellion of 1641. The rebellion was betrayed by spies and Ireland descended into chaos, including sectarian communal violence, until the Irish Confederation was established.

In 1644, in response to the threat of the Confederate Irish; nominally loyal to Charles I Stuart, but independent of the Royalist Army in Ireland; possibly sending troops to aid the embattled Stuart monarch in the English Civil War, the Long Parliament issued an ordinance of "no quarter to the Irish" fighting on English soil. A minority of the 8,000 troops sent by the Duke of Ormonde from Munster to fight for the king were native Irish and so the policy did see some application. The Parliamentarians under Thomas Mytton killed Irish prisoners of war at Shrewsbury in 1645[4][5] and Conway Castle in 1646. After the Battle of Naseby over 100 Welsh-speaking women were massacred by the Roundheads, who mistook them for Irish-speakers.[6]

Regimentalisation and modern Army

Papists Act 1778, Napoleonic and Victorian-eras

Some of the Penal Laws against Catholics were reversed with the Papists Act 1778, which was passed by the Parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland. This allowed for Catholics to own property, inherit land and join the British Army. The British Army needed soldiers to fight in the contemporary American Revolutionary War and had made some concessions to North American Catholics with the Quebec Act earlier in 1774. Despite ensuing ultra-Protestant riots in Scotland and also the Gordon Riots in London against reversing the ban, many Irish Catholics from this point on would use it as an opportunity for employment. It has been estimated that during the North American conflict, from the British Army 16% of the rank and file and 31% of the COs were Irishmen.[7] There were Irishmen fighting on both sides; a standout story from the diary of Sergeant Roger Lamb recalls how Patrick Maguire of the 9th Regiment of Foot spotted his own brother fighting on the side of the American Patriots during the Saratoga campaign.[8] In following years, the Irish would swell the ranks to the extent that by 1813 the British Army's total manpower was "1/2 English, 1/6 Scottish and 1/3 Irish."[9]

In the aftermath of the French Revolution a new period of conflict arose. The United Irishmen was created by radical liberals of Protestant background, such as Wolfe Tone, Edward FitzGerald and Henry Joy McCracken. In collaboration with the French Republic, they sought to set up their own republic in Ireland; appealing to Irish Catholics (particularly elements of the Defenders) to be their sans-culottes. In 1793, the Volunteers was replaced with new government groups; the Militia and the Yeomanry. These latter organisations initially had a higher numbers of Irish Catholic members, but as the Irish Rebellion of 1798 gained ground in Wexford and the Wicklow Mountains, some Catholics were purged due to suspected United Irish sympathies.[10] Lord Castlereagh also secretly adopted a policy of supporting the newly formed Orange Order (successors of the Peep o' Day Boys) in Ulster, to dissuade Presbyterian United Irish membership.[10] Orangism then spread into the Yeomanry and Militia.[10]

Despite the large number of deaths in the United Irish conflict, Irishmen; Catholic and Protestant; flocked to join the British Army and the Royal Navy with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe.[11] Some republicans on the other hand formed the pro-Bonapartist Irish Legion.[12] The Ireland-born Duke of Wellington led the British to a famous victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The main Irish regiments involved in the Napoleonic Wars were the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, 18th Royal Hussars, 27th Regiment of Foot, 87th Regiment of Foot and the 88th Regiment of Foot.[13] Of the 27th Inniskilling Regiment, Bonaparte himself said; "anything to equal the stubborn bravery of the Regiment with castles in their caps I have never before witnessed."[14] At the other famous British victory of the Napoleonic Age a decade earlier; the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805; around a quarter of the Royal Navy crew present (3,573 people) were Irishmen.[15][16] A monument to Horatio Nelson, known as Nelson's Pillar, designed by architects William Wilkins and Francis Johnston, with the statue sculpted by Thomas Kirk, was built from 1808 to 1809 in Dublin, Ireland.

Within the context of Ossianic romanticism, the writer Walter Scott had taken some of the Philo-Gaelic ideals of James Macpherson and produced a "British Isles nationalism" for the 19th century Victorian Age, within which Gaelic cultural motifs had something of a place (critics deride this tendency as "Balmoralism").[17] This extended to the regiments of the British Army, which incorporated elements of Highland and Irish national costume into its dress. This idealisation of the "Gaelic warrior," as a noble savage of sorts had consequences for military-associated race theory of the day. British authorities would classify the Gaelic Irish peasantry, along with their Highland Scots cousins and peoples as far removed as the Gurkhas, Rajputs and Sikhs as martial races, most suited to the hardships of warfare (although, the Irish were typically described as more emotional than Highlanders and sometimes questions were raised as to their Imperial loyalty). In part, the British Raj derived this martial race concept from the Vedic varna known as the Kshatriya.[18]

I am full willing to leave my manson and to go into the interiors of Africa to fight vountarilly for Queen Victoria and as far as there is life in my bones and breath in my body, I will not let any foreign invasion tramp on Queen's land. However, if her or her leaders ever turns with cruelty on the Irish race, I will be the first to raise my sword to fight against her. I will have plenty of Irishmen at my side, for they are known to be the bravest race in the world.

Service during World War I and World War II

During World War I, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which entered the war in August 1914 as one of the Entente Powers. Occurring during Ireland's revolutionary period, the Irish people's experience of the war was complex and its memory of it divisive. At the outbreak of the war, many Irish people, regardless of political affiliation, supported the war in much the same way as their British counterparts,[20] and both nationalist and unionist leaders initially backed the British war effort. Irishmen, both Catholic and Protestant, served in the British forces, many in three specially raised divisions, while others served in the armies of the British dominions and the United States. Over 200,000 men from Ireland fought in the war, in several theatres. About 30,000 died serving in Irish regiments of the British forces,[21] and as many as 49,400 may have died altogether. After WWI, Irish republicans won the Irish general election of 1918 and declared independence. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919–1922), fought between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces. Irish ex-servicemen fought for both sides. Some aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which ended the war, resulted in a split in Ireland's nationalist forces and lead to the Irish Civil War (1922–1923) between pro-treaty and anti-treaty forces.

During World War II, Ireland was now officially neutral and independent from the UK. However, over 80,000 Irish-born men and women (north and south) joined the British armed forces, with between 5,000 and 10,000 being killed during the conflict.[22][23]

The Troubles

The Troubles and the following Operation Banner taking place in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2006 marked a new phase in the relationship between Irish people and the British Armed Forces. Initially, the Irish national community in the North were glad that the British Army had been deployed with a remit to halt communal violence from Ulster loyalists. Some Irish people did not trust the Royal Ulster Constabulary to be impartial, due to perceptions of sectarian biases and the Irish Republican Army had stockpiled weapons, ostensibly to "defend their areas." When the Falls curfew was called in 1970, with the British Army searching civilian properties for illegal weapons, the situation quickly deteriorated. Militant republicans such as the PIRA launched an urban guerrilla warfare campaign with the hopes of forcing a secession of the North from the United Kingdom, with a goal to bring about a United Ireland.

In attempting to distinguish between civilians and combatants, some atrocities occurred on all sides, especially during the 1970s. A notable example in 1972 was Bloody Sunday in Derry, associated with the Parachute Regiment (already regarded as heavy handed by the Irish nationalist community across the board).[24] The Scottish regiments which were deployed, such as the Black Watch, were perceived by Irish nationalists as being particularly sympathetic to Orangism and Ulster loyalism, due in part to a similar socio-political culture of sectarianism in Scotland.[24][25] For the Irish diaspora in Britain, bombings by the PIRA in England led some to either emphasise the credentials of their own Britishness, including championing the suppression of paramilitary forces by the state, or for a minority, participating in organisations such as the Troops Out Movement formed in 1973 (also consisting of some English people), which aligned itself with Irish republicanism by advocating a British disengagement and withdrawal from Northern Ireland.

With the ending of the Cold War, the Royal Irish Rangers and the Ulster Defence Regiment were amalgamated to form the Royal Irish Regiment in 1992.

Into the 21st century

Since the emergence of the Northern Ireland peace process and the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, with Sinn Féin entering into a power sharing agreement with unionists, tensions have died down somewhat, although a low level Dissident Irish Republican campaign continues. Thousands of Irish people have continued to find employment in all branches of the British Armed Forces and this trend has been increasing in recent years, especially since the economic implosion of the Celtic Tiger in 2008.[26][27] When the British monarch Elizabeth II and her husband made a conciliatory state visit to Ireland in 2011, Major General David O'Morchoe, president of The Royal British Legion in the Republic of Ireland[28] (and head of the Ó Murchadha, a Gaelic sept of the Uí Ceinnselaig), gave her and Mary McAleese, president of Ireland a tour of the Irish National War Memorial Gardens.[29]

In 2000, an estimated 1000 Irish citizens served in the British armed forces, 232 of whom were in the army.[30] As of 2011, recruits from the Republic of Ireland together with Commonwealth recruits made up roughly 5% of annual recruitment to the British armed forces. During 2017 a recruit from the Republic of Ireland was signed up to the British armed forces every four and a half days. 230 Irish citizens signed up to the British armed forces from 2013 to 2015.[31]

Subjects

Prominent figures

Ireland-born

During the Second World War, some notable Irish personalities who fought for Britain were Victoria Cross winners such as Donald Garland and Eugene Esmonde of the Royal Air Force and James Joseph Magennis of the Royal Navy. The best known of the Irish from among The Few who fought in the Battle of Britain was Brendan Finucane. In the aftermath of the Liverpool Blitz, Dublin-born James Scully won a George Cross for his actions.

Victoria Cross recipients

Many Ireland-born people have been awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry available to members of the British Armed Forces. In fact, from the nations which were part of the British Empire, the only country which has more winners is England with 614. Ireland, with 190 awards (not including Irish diaspora born abroad), outranks Scotland who have 158 and Australia who have 97. When awards per number of people in the total population are taken into account, Ireland's awards would be the equivalent of England gaining 2,850 Victoria Crosses.[32] Charles Davis Lucas of the Royal Navy from County Armagh was the man whose actions were the earliest to be rewarded with a Victoria Cross, due to his actions in the Baltic Sea on 21 June 1854.[33]

This propensity for Irish servicemen to win a disproportionate amount of Victoria Crosses received satirical treatment from Dublin playwright George Bernard Shaw in his 1915 play O'Flaherty V.C., A Recruiting Pamphlet. The play in some parts derives inspiration from the case of Michael John O'Leary. Within it Shaw tells the story of an Irishman from a nationalist family background who joins the British Army simply to escape the hum-drum existence of home life and to seek out adventure abroad. He does not know or care about the "reasons" for the war, nor for British patriotism, but he wins a Victoria Cross in the process. The British military and civil authorities were able to pressure the Abbey Theatre into censoring Shaw's play at the time.

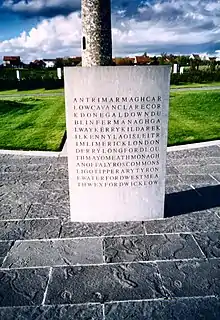

Monuments and remembrance

War memorials exist on the island of Ireland dedicated to Irish personnel who served in the British Armed Forces over the centuries; some of these memorials originate from Victorian-times.[34] Monuments of local significance include one at Kickham Barracks, a prominent Gaelic cross for the Royal Munster Fusiliers at Killarney, monuments to the Connaught Rangers and Irish Guards at the County Mayo Peace Park and Garden of Remembrance in Castlebar, the Belfast War Memorial in Donegall Square West and a number of monuments inside churches, particularly Anglican ones such as St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. Aside from these memorials based in Ireland, Irish surnames also feature prominently on war memorials in a great many towns and cities across Great Britain itself.

The most prominent memorial is dedicated to the 49,400 Irish soldiers who died during World War I; this is the Irish National War Memorial Gardens, at Islandbridge in Dublin. It was designed by Edwin Lutyens and first planned in 1919 and was completed in 1938, at a time when Ireland had achieved independence. Despite being a monument to people who fought in the British Army, it received cross-party support, partly because the likes of Major General William Hickie had been Home Rulers. There are a number of other major monuments relevant to the experience of Irish soldiers in World War I, this time based on the European continent; the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, for example, features the names of many Irish soldiers.[35][36] A second Belgium-based memorial was opened in 1998; the Island of Ireland Peace Park. There also exists in Thiepval, France, a monument called the Ulster Tower to the men who died at the Battle of the Somme.

Involvement in the Dominions

World War II veterans

During the Second World War, Ireland maintained a policy of neutrality and was not a military combatant in the conflict. Aside from a far larger number of previously non-attached Irish-born persons who served in World War II,[37] 4,987 recorded members of the Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireann) deserted their positions to join combatant nations, primarily the British Armed Forces during what is known as The Emergency. In response to this and to deter further desertions, Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, enacted EPO 362 in 1945 which deprived deserters of an Irish pension, previously accrued unemployment benefits and banned them from jobs in the public sector for 7 years. At the time this was much debated, with some such as Thomas F. O'Higgins and Patrick McGilligan strongly arguing against the act, while Matthew O'Reilly argued that it was a lenient punishment for the crime of desertion.

The historical perception of the topic and the legacy of the treatment of these men when they returned to Ireland after the war, has become an increasingly contested issue in the 21st century.[38] Defenders of the Fianna Fáil Government's actions assert that the British Government would not tolerate desertion from their Armed Forces under military law, and in fact during the First World War, 306 British soldiers were executed for going so (including 22 serving Irishmen). Supporters of the "deserters" typically state that they were fighting an "ultimate evil" in the form of Nazi Germany.

In May 2011 a pressure group was formed in Ireland entitled the 'Irish Soldiers Pardons Campaign', seeking formal acknowledgement from the Irish State that soldiers in its employ who had illegally left the Irish Defence Forces to enlist with the British Government's Arms in World War 2 had been unjustly defamed and treated by the Irish Government's actions, which involved financial penalties being laid upon them by the state when they returned home post-war and employment blacklisting.[39] Public petitions were organized and a media engagement publicity campaign was launched. In June 2013 the Irish Government's Minister for Defence, Alan Shatter, gave a statement in the Dáil Éireann making a formal apology by the Irish Government for its treatment of Irish veterans from the conflict. The Government subsequently passed into law the '(Second World War Amnesty & Immunity) Act (No.12) 2013', granting formal legal amnesty to all Irish Defence Force personnel who had left their posts to enlist with the British Arms in the conflict.[40][41]

Irish republican opposition

The broader movement of Irish nationalism; particularly those of a Home Rule or reformist disposition; was not necessarily hostile to Britain or Irish participation in the British Armed Forces and indeed had some supporters up until the end of the First World War, such as the National Volunteers who were supporters of John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party. The doctrines of Irish republicanism have traditionally upheld a harder line. Republicans by nature advocate "breaking the connection with England" in total: an All-Ireland sovereign nation state under a republican form of government, with no British involvement. From the beginning in the late 1700s, Irish republicanism has tended to employed two tactics: (1) portray the British state and its security forces in propaganda as a hostile, alien, occupational force (2) infiltrate militant republicans into the British military to gain practical experience in soldiering.

A number of men who later became prominent Irish republican militants had at some point served in the British Army, this includes; James Connolly, Tom Barry, Martin Doyle (a Victoria Cross winner), Emmet Dalton, Erskine Childers and in more recent times John Joe McGee. Aside from the obvious paramilitary opposition to Irish involvement in the British Armed Forces, the Irish rebel song tradition has developed which also voices opposition to Irish enlistment or criticised the actions of the British forces in Ireland. Some of the best known of these include; Join the British Army, The Recruiting Sergeant, Foggy Dew, Come Out Ye Black and Tans, Who Is Ireland's Enemy?, Go On Home, among others. Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye and McCafferty, while not of republican origin, carry much of the same spirit.

'Twas England bade our Wild Geese go, that "small nations might be free",

But their lonely graves are by Suvla's waves on the fringe of the great North Sea.

Oh, had they died by Pearse's side or fought with Cathal Brugha,

Their names we'd keep where the Fenians sleep, 'neath the shroud of the Foggy Dew.— Canon Charles O’Neill, Foggy Dew, 1919.

Gaelic games participation

As part of the general Gaelic Revival of the 19th century, the Gaelic Athletic Association was created to organise and promote the restoration of Gaelic games such as hurling and Gaelic football. These were seen as native Irish cultural alternatives to British-directed sports such as rugby union, association football and cricket. Thirteen years after its creation, the GAA enacted Rule 21 in 1897, which banned all members of the British Armed Forces and the police from participation; both in Ireland and Great Britain itself. Although, like with other institutions such as the Gaelic League, the original principles of the GAA was to be apolitical, militant republicans from the Irish Republican Brotherhood joined and became influential within the organisations. Rule 21 was enforced primarily to stop members of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan Police from spying on nationalistic GAA members.

After the secession of most of Ireland as the Irish Free State and the partition of Ireland, which led to the creation of Northern Ireland, the rule continued to be in place. Particularly during The Troubles, there was a climate of mutual suspicion, as some Ulster unionists regarded elements of the GAA as sympathetic in some ways to the goals of the Provisional IRA and at the same time, the GAA (especially in the North) were suspicious of Royal Ulster Constabulary personnel wishing to join. As part of the Northern Ireland peace process and the reforming of the police into a more cross-community institution, as the Police Service of Northern Ireland, moves were made to lift the ban. In 2001, during the presidency of Seán McCague, the ban was lifted, with 26 counties voting yes. Members of the Irish diaspora[42] serving in the Irish Guards founded the Gardaí Éireannach as part of the London GAA in 2015.[43][44]

Regiments

Towards the end of the 17th century, a number of regiments began to develop which swore allegiance to the British interest; most of these derive from the Williamite War in Ireland. Most of the early "Irish" Regiment of Foot were founded by New English settlers, however, an exception is the 5th Regiment of Foot (later known as the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers) deriving its lineage from Daniel O'Brien, 3rd Viscount Clare. A slew of red-coated regiments were founded during the Napoleonic Wars, not least the Royal Irish Fusiliers founded by Sir John Doyle, 1st Baronet. At the height of the British Empire, regiments such as the Connaught Rangers emerged. The Irish Guards was founded during the Victorian-era. Many regiments were disbanded after Irish independence, but an association exists today to commemorate the history and servicemen in the form of the Combined Irish Regiments Association.

A number of contemporary British regimental traditions make reference to Irish culture. The regimental motto of the Royal Irish Regiment; Faugh A Ballagh (Clear the Way!); is in the Irish language. The only other British regiment to feature one of the Gaelic languages as a motto was the Seaforth Highlanders, with Cuidich 'n Righ (Aid the King). Meanwhile, the Royal Dragoon Guards and the Irish Guards have as their motto Quis separabit? (Who will separate?) which was also used previously by the Connaught Rangers. An Irish harp with a crown features on the regimental cap badge of the Royal Irish and the Queen's Royal Hussars, while the shamrock and Cross of St. Patrick is featured on the Irish Guards' cap badge. Marching songs in use include the Killaloe March and Eileen Alannah for the Royal Irish, Fare Thee Well Inniskilling for the Royal Dragoon Guards, St Patrick's Day and Let Erin Remember for the Irish Guards. These regiments also celebrate St Patrick's Day on 17 March and are presented with shamrocks. The Royal Irish and the Irish Guards have an Irish Wolfhound as their military mascot, named "Brian Boru IX" and "Domhnall," respectively.

Extant

| Regiment | Active | Lineage and details |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Irish Regiment | 1689–present | The present regiment was founded by a merger of the Royal Irish Rangers and the Ulster Defence Regiment. Also includes among its lineage, the Royal Irish Rifles, the Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, as well as earlier Regiment of Foot. |

| Irish Guards | 1900–present | Part of the Guards Division, founded by order of Queen Victoria to commemorate the Irishmen who fought in the Second Boer War. The regiment are also known as the Fighting Micks. Like other Guards regiments, the Irish Guards wear bearskins and redcoats as their ceremonial dress. |

| Queen's Royal Hussars | 1685–present | This cavalry regiment also features among its ancestors English and Scottish forefathers, but the Irish lineage derives from the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars, which later became the Queen's Royal Irish Hussars. They are famously associated with the Charge of the Light Brigade. |

| Royal Dragoon Guards | 1685–present | This cavalry regiment descends from the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, the 7th Dragoon Guards, the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons and the 5th Dragoon Guards, all of which were at some point Irish-based regiments. Today the Dragoons have a joint Yorkshire and Irish identity. |

| Royal Lancers | 1689–present | This cavalry regiment descends from the 5th Royal Irish Lancers (16th/5th Lancers), the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers, 12th Royal Lancers, the 16th The Queen's Lancers (16th/5th Lancers), 17th Lancers and the 21st Lancers. Today, the Lancers's four current Sabre Squadrons are each named after one of the antecedent Regiments.[45] |

| Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry | 1902–present | Originated as the North Irish Horse, yeomanry cavalry regiment founded in the aftermath of the Second Boer War and was revived during the Second World War. The North Irish Horse is currently C Squadron of the regiment, based in Belfast and Coleraine. |

| London Irish Rifles | 1859–present | Originated as a Victorian volunteer rifle regiment, to represent the Irish diaspora in London, who had arrived in large numbers during the 19th century. It was associated with the Royal Ulster Rifles during the early 20th century. Today it forms D Company of the London Regiment. |

| Liverpool Irish | 1860–present | Originated as a Victorian volunteer rifle regiment, to represent the Irish diaspora in Liverpool, who had arrived in large numbers during the 19th century. It was associated with the King's Regiment (Liverpool) from an early time. Today it forms A Troop of the 208th (3rd West Lancashire) Battery Royal Artillery in the 103rd (Lancashire Artillery Volunteers) Regiment Royal Artillery. |

| Antrim Fortress Royal Engineers | 1938–present | When the TA was reconstituted in 1947, 591 (Antrim) Independent Field Sqn reformed in two Nissen huts at Girdwood Park, Belfast, forming part of 107th (Ulster) Brigade. In 1956 the coast artillery branch was disbanded, and the Antrim unit first raised in 1937 was transferred to the RE as 146 (Antrim Artillery) Corps Engineer Regiment. Following the 1966 Defence White Paper 107 (Ulster) Bde was disbanded and 591 Sqn was placed in suspended animation, but the following year it was reformed and amalgamated with 146 Rgt as 74 (Antrim Artillery) Engineer Regiment, forming 112 (Antrim Fortress) Field Squadron. In 1993 the regiment was reduced to a single squadron, 74 (Antrim Artillery) Independent Field Sqn at Bangor, County Down. This in turn was disbanded under the Strategic Defence Review in 1999. A new 591 (Antrim Artillery) Field Sqn was formed at Balloo TA Centre, Bangor, in October 2006 and continues the traditions. |

| 206 (Ulster) Battery Royal Artillery | 1967–1999 | Formed on 1 April 1967 as 206 (Coleraine) Light Air Defence Battery Royal Artillery (Volunteers) from 245 (Ulster) Light Air Defence Regiment RA (TA). |

| 152 (North Irish) Regiment RLC | 1967–present | The regiment was formed in the Royal Corps of Transport (RCT) in 1967 with two transport squadrons.[1] It was redesignated 152 (Ulster) Ambulance Regiment RCT in the 1980s, and transferred into The Royal Logistic Corps (RLC) in 1993 as 152 (Ulster) Ambulance Regiment RLC. |

| 204 (North Irish) Field Hospital | 1967–present | The 204th Field Hospital was originally formed in 1967 known then as 204th (North Irish) General Hospital. |

Amalgamated

| Regiment | Active | Lineage and details |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Royal Irish Lancers | 1689–1799 1858–1922 | This cavalry regiment was disbanded in 1922, with many other Irish regiments, but a squadron from it was amalgamated with the English regiment 16th The Queen's Lancers to become the 16th/5th The Queen's Royal Lancers. For a brief time this became the Queen's Royal Lancers and more recently the Royal Lancers. The Royal Lancers: the Regiment's four current Sabre Squadrons are each named after one of the antecedent Regiments (one of which was the 5th Royal Irish Lancers or 16th/5th Lancers) - https://www.ciroca.org.uk/home/the-irish. |

| 5th Regiment of Foot | 1674–1968 | This regiment was founded by the Irish nobleman Daniel O'Brien, 3rd Viscount Clare as part of the Dutch States Army. Not to be confused with the Clare's Dragoons. It transferred to the English forces in 1685. The regiment later became known as the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers before being amalgamated into the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. |

Disbanded

See also

References

- ↑ Number of Irish recruits joining British Army stable again following dissident republican death threats at www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 13 Nov 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Beyond Reform: Martial Law & the Tudor reconquest of Ireland". History Ireland. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "A Poem on the Downfall of the Gaoidhil". BBC. 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Carlton 1994, p. 262.

- ↑ "Shrewsbury, the house at the Castle Gates and the hanged Irish mercenaries". Gwendda. 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "Wales and the Civil War". Spartacus Educational. 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Holmes 2002, p. 53.

- ↑ "'My Brother! My Dear Brother': The Extraordinary Encounter of an Irish Redcoat & Rebel During the War of Independence". Irish American Civil War. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Snape 2013, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 "A Forgotten Army; The Irish Yeomanry". History Ireland. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Chappell 2003, p. 5.

- ↑ "Napoleon's Irishmen at Waterloo". The Irish Story. 5 December 2015. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015.

- ↑ Chappell 2003, p. 7.

- ↑ Bredin 1987, p. 276.

- ↑ "England expects, with a little help from Nelson's Irish". The Irish Times. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Were they one of Nelson's men?". BBC News. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Balmorality runs rampant". The Scotsman. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Streets 2004, p. 169.

- ↑ "Irish Soldiers in the British Army, 1792-1922: Suborned or Subordinate?". Journal of Social History. 5 December 2015. JSTOR 3787238.

- ↑ Pennell, Catriona (2012). A Kingdom United: Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199590582.

- ↑ David Fitzpatrick, Militarism in Ireland, 1900–1922, in Tom Bartlet, Keith Jeffreys ed's, p. 397

- ↑ "In service to their country: Moving tales of Irishmen who fought in WWII". irishexaminer.com. Irish Examiner. 29 August 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ↑ "The Forgotten Volunteers of World War II". historyireland.com. History Ireland Magazine. 1998. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- 1 2 Sanders 2012, p. 169.

- ↑ "The Scottish soldiers dogged by accusations of sectarianism". Scottish Review. 5 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "Record numbers of Irish recruits join British army". The Irish Independent. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "The fighting Irish". The Irish Times. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "On tour with the Royal British Legion as they bus to see the queen". The Irish Times. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Royal British Legion president in Republic suspended". News Letter. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Army now `battling' with British for new recruits". Irish Independent. 16 August 2000. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ↑ Riegel, Ralph (4 January 2017). "Recruitment for British Army soars in Republic of Ireland". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ↑ "The Victoria Cross - Irish Domination". Irish Identity. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Little Cross of Bronze". RTÉ. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Wars". Irish War Memorials. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "50,000 Irish soldiers no longer forgotten". Irish Examiner. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Traitors, martyrs or just brave men?". The Independent. 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Forgotten Volunteers of World War II". History Ireland. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "Time to ask questions about Irish army deserters during World War II". The Journal. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Interview with the organizer of the [Irish Soldiers' Pardons Campaign', Irish Seamen's Relatives website (2018). http://www.irishseamensrelativesassociation.com/for-the-sake-of-example.htm

- ↑ 'Government apologizes for treatment of World War 2 veterans', 'The Journal.ie.', 12 June 2012. https://www.thejournal.ie/irish-wwii-veterans-allies-apology-484431-Jun2012/

- ↑ "WWII Irish 'deserters' finally get pardons". BBC. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "Irish Guards step into the British GAA limelight". Irish Post. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "Irish Guards: Regiment becomes first British Army club in GAA". BBC News. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "GAA made right decision to allow Irish Guards team join London branch". Irish Times. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "Combined Irish Regiments - the Queen's Royal Lancers".

Bibliography

- Blythe, Robert J (2006). The British Empire and its Contested Pasts. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0716530169.

- Bowen, Desmond (2015). Heroic Option: The Irish in the British Army. Leo Cooper Ltd. ISBN 978-1844151523.

- Bowman, Timothy (2006). The Irish Regiments in the Great War: Discipline and Morale. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719062858.

- Bredin, A. E. C. (1987). A History of the Irish Soldier. Century Books. ISBN 978-0903152181.

- Bredin, H. E. N. (1994). Clear the Way!: History of the 38th (Irish) Brigade, 1941–47. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2542-9.

- Carlton, Charles (1994). Going to the Wars: The Experience of the British Civil Wars 1638-1651. Routledge. ISBN 0415103916.

- Chappell, Mike (2003). Wellington's Peninsula Regiments (1): The Irish. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1841764023.

- Dancy, J. Ross (2015). The Myth of the Press Gang: Volunteers, Impressment and the Naval Manpower Problem in the Late Eighteenth Century. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1783270033.

- Document, Official (2011). List of Personnel of the Irish Defence Forces Dismissed for Desertion During the Second World War. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1845748883.

- Doherty, Richard (2000). Irish Winners of the Victoria Cross. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1851824427.

- Durney, James (2014). Irish Casualties in the Korean War 1950-53. Gaul House. ISBN 978-0954918057.

- Garnham, Neal (2012). The Militia in Eighteenth-Century Ireland: In Defence of the Protestant Interest. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843837244.

- Grayson, Richard S. (2010). Belfast Boys: How Unionists and Nationalists Fought and Died Together in the First World War. Continuum. ISBN 978-1441105196.

- Guards, Irish (1999). Irish Guards: The First Hundred Years, 1900-2000. Spellmount Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1862270695.

- Harris, R G (2001). The Irish Regiments: 1683-1999. Da Capo Press Inc. ISBN 1885119623.

- Harvey, Dan (2015). A Bloody Day: The Irish at Waterloo. Drombeg Books. ISBN 978-0993114359.

- Holmes, Richard (2002). Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-653152-0.

- Johnstone, Tom (1994). Orange, Green & Khaki: The Story of the Irish Regiments in the Great War, 1914-18. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717119943.

- Kenny, Mary (2009). Crown and Shamrock: Love and Hate Between Ireland and the British Monarchy. New Island Books. ISBN 978-1905494989.

- Kelly, Bernard (2012). Returning Home: Irish Ex-Servicemen After the Second World War. Merrion. ISBN 978-1908928009.

- McCabe, Richard Anthony (2002). Spenser's Monstrous Regiment: Elizabethan Ireland and the Poetics of Difference. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198187349.

- McCallum, Ian (2013). The Celtic, Glasgow Irish and the Great War: The Gathering Storms. Mr Ian McCallum BEM. ISBN 978-0-9541263-2-2.

- Murray, Robert H (2005). History of the VIII King's Royal Irish Hussars 1693-1927. Naval & Military Press Ltd. ISBN 1845741420.

- Nelson, Ivan F. (2007). The Irish Militia, 1793–1802, Ireland's Forgotten Army. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-037-3.

- O'Connor, Steven (2014). Irish Officers in the British Forces, 1922–45. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-35085-5.

- O'Dowd, Gearóid (2011). He Who Dared and Died: The Life and Death of a SAS Original, Sergeant Chris O'Dowd, MM. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1848845411.

- Pakenham, Thomas (2000). The Year Of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1789: History of the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798. Abacus. ISBN 978-0349112527.

- Palmer, Patricia (2013). The Severed Head and the Grafted Tongue: Literature, Translation and Violence in Early Modern Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107041844.

- Reid, Stuart (2011). Armies of the Irish Rebellion 1798. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1849085076.

- Renwick, Aly (2004). Oliver's Army: A History of British Soldiers in Ireland and Other Colonial Conflicts. Troops Out Movement. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Richardson, Neil (2015). According To Their Lights: Irish Soldiers in the British Army during the Easter Rising, 1916. The Collins Press.

- Sanders, Andrew (2012). Times of Troubles: Britain's War in Northern Ireland. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748655137.

- Sheehan, William (2011). The Western Front: Irish Voices from the Great War. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717147861.

- Shepherd, Gilbert Alan (1972). Connaught Rangers. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0850450835.

- Snape, Michael (2013). The Redcoat and Religion: The Forgotten History of the British Soldier from the Age of Marlborough to the Eve of the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136007422.

- Streets, Heather (2004). Martial Races: The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857-1914. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719069628.

- Taylor, Peter (2002). Brits: The War Against the IRA. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 074755806X.

- Verney, Peter (1970). The Micks: The Story of the Irish Guards. P. Davies. ISBN 978-0432186503.

- Widders, Peter (2010). Spitting on a Soldier's Grave: Court Martialed After Death, the Story of the Forgotten Irish and British Soldiers. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1848764996.

External links

- The position of Irish Catholics within the Officer Corps of the British Army: 1829-1899 at NUI Galway

- The Irish Sea-Officers of the Royal Navy, 1793-1815 by Anthony Gary Brown

- Combined Irish Regiments Association at CIORCA

- Irish Soldiers of the British Army at Clann DubhGhaill

- Irish Fighting Irish by Barry McGinn