San Giorgio firing her secondary armament in 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | San Giorgio |

| Namesake | Saint George |

| Ordered | 3 August 1904 |

| Builder | Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia, Castellammare di Stabia |

| Laid down | 4 July 1905 |

| Launched | 27 July 1908 |

| Completed | 1 July 1910 |

| Stricken | 18 October 1946 |

| Honours and awards | Gold Medal of Military Valor (Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare) |

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | San Giorgio-class armoured cruiser |

| Displacement | 10,167 t (10,006 long tons) |

| Length | 140.89 m (462 ft 3 in) (o/a) |

| Beam | 21.03 m (69 ft 0 in) |

| Draught | 7.35 m (24 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 2 vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Range | 6,270 nmi (11,610 km; 7,220 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 32 officers, 666–73 enlisted men |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

The Italian cruiser San Giorgio was the name ship of her class of two armored cruisers built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the first decade of the 20th century. Commissioned in 1910, the ship was badly damaged when she ran aground before the start of the Italo-Turkish War in 1911, although she was repaired before its end. During World War I, San Giorgio's activities were limited by the threat of Austro-Hungarian submarines, although the ship did participate in the bombardment of Durazzo, Albania, in late 1918.

She acted as a royal yacht for Crown Prince Umberto's 1924 tour of South America and then deployed to the Indian Ocean to support operations in Italian Somaliland in 1925–1926. San Giorgio served as a training ship from 1930 to 1935 and was then rebuilt in 1937–1938 to better serve in that role. As part of her reconstruction, she received a modern anti-aircraft suite that was augmented before she was transferred to bolster the defences of Tobruk shortly before Italy declared war on the Allies in mid-1940. San Giorgio was forced to scuttle herself in early 1941 as the Allies moved in to occupy the port. Her wreck was used as an immobile repair ship by the British from 1943 through 1945. Salvaged in 1952, she sank while under tow to Italy to be broken up.

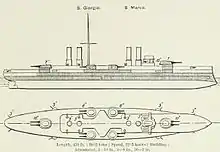

Design and description

The ships of the San Giorgio class were designed as improved versions of the Pisa-class design. San Giorgio had a length between perpendiculars of 131.04 metres (429 ft 11 in) and an overall length of 140.89 metres (462 ft 3 in). She had a beam of 21.03 metres (69 ft 0 in) and a draught of 7.35 metres (24 ft 1 in). The ship displaced 10,167 tonnes (10,006 long tons) at normal load, and 11,300 tonnes (11,100 long tons) at deep load. Her complement was 32 officers and 666 to 673 enlisted men.[1]

The ship was powered by a pair of vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller shaft using steam supplied by 14 mixed-firing Blechynden boilers. Designed for a maximum output of 23,000 shaft horsepower (17,000 kW) and a speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph),[2] San Giorgio handily exceeded this, reaching a speed of 23.2 knots (43.0 km/h; 26.7 mph) during her sea trials from 19,595 ihp (14,612 kW).[3] The ship had a cruising range of 6,270 nautical miles (11,610 km; 7,220 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3]

The main armament of the San Giorgio-class ships consisted of four Cannone da 254/45 A Modello 1908 guns in twin-gun turrets fore and aft of the superstructure. The ships mounted eight Cannone da 190/45 A Modello 1908 in four twin-gun turrets, two in each side amidships, as their secondary armament. For defense against torpedo boats, they carried 18 quick-firing (QF) 40-caliber 76 mm (3.0 in) guns. Eight of these were mounted in embrasures in the sides of the hull and the rest in the superstructure.[3] The ships were also fitted with a pair of 40-caliber QF 47 mm (1.9 in) guns. The San Giorgios were also equipped with three submerged 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. During World War I, eight of the 76 mm guns were replaced by six 76 mm anti-aircraft (AA) guns[3] and one torpedo tube was removed.[2]

The ships were protected by an armoured belt that was 200 mm (7.9 in) thick amidships and reduced to 80 mm (3.1 in) at the bow and stern.[2] The armoured deck was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick and the conning tower armour was 254 mm thick. The 254 mm gun turrets were protected by 200 mm of armour while the 190 mm turrets had 160 mm (6.3 in).[3]

Construction and career

San Giorgio, named after Saint George, the patron saint of Genoa,[4] was ordered on 3 August 1904 and laid down on 2 January 1907 at the Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia in Castellammare di Stabia. The ship was launched on 27 July 1908 and completed on 1 July 1910.[3] San Giorgio ran aground on a reef off Naples-Posillipo on 12 August 1910, and was badly damaged. An estimated 4,369 tonnes (4,300 long tons) of water flooded the boiler rooms, magazines and lower compartments. To refloat the ship, her guns and turrets, together with her conning tower and some of her armour had to be removed.[5]

_stranded_1913.jpg.webp)

San Giorgio was under repair at the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War in September and only rejoined the fleet in June 1912.[6] In February 1913, the ship cruised the Aegean Sea and made a port visit to Salonica, Greece, the next month.[7] The ship ran aground again in November in the Strait of Messina, but she was only lightly damaged. The captain was dismissed as a result of the incident.[8]

San Giorgio was based at Brindisi when Italy declared war on the Central Powers on 23 May 1915. That night, the Austro-Hungarian Navy bombarded the Italian coast in an attempt to disrupt the Italian mobilization. Of the many targets, Ancona was hardest hit, with disruptions to the town's gas, electric, and telephone service; the city's stockpiles of coal and oil were left in flames. All of the Austrian ships safely returned to port, putting pressure on the Regia Marina to stop the attacks. When the Austrians resumed bombardments on the Italian coast in mid-June, Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel responded by sending San Giorgio and the other armored cruisers at Brindisi—the navy's newest—to Venice to supplement the older ships already there.[9] Shortly after their arrival at Venice, Amalfi was sunk by a submarine on 7 July and her loss severely restricted the activities of the other ships based at Venice.[10] San Giorgio participated in the bombardment of Durazzo on 2 October 1918 which sank one Austro-Hungarian merchantman and damaged two others.[11]

San Giorgio was relieved by the scout cruiser Brindisi as flagship of the Eastern Squadron on 16 July 1921 at Istanbul, Turkey.[12] She later served in the Far East and China. In 1924 she conducted Crown Prince Umberto on his tour of South America. The ship departed Naples on 1 July[13] and the outbreak of the second Tenente revolt in Brazil the following day forced the ships to divert to Argentina,[14] where they arrived at Buenos Aires on 6 August.[15] Three days later the government hosted a military parade in his honor which included a detachment of sailors from San Giorgio.[16] He visited Chile before departing Montevideo, Uruguay on 5 September,[17] bound for Bahia, Brazil. The ship sailed for home on 18 September.[18]

After her return, she was assigned to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean Naval Division (Divisione Navale del Mar Rosso e dell'Oceano Indiano) in 1925–1926, supporting operations in Italian Somaliland. From 1930 to 1935, the ship was based in Pola as a training ship for naval cadets and was sent to Spain after the Spanish Civil War began in 1936 to protect Italian interests.[19] In 1937–1938 she was reconstructed to serve as a dedicated training ship for naval cadets at the Arsenale di La Spezia: six boilers were removed and the remaining eight were converted to burn fuel oil which reduced her speed to 16–17 knots (30–31 km/h; 18–20 mph). Each pair of funnels was trunked together and her 76/40 guns were replaced by eight 100 mm (4 in) / 47 caliber guns in four twin turrets abreast the funnels. Her torpedo tubes were also removed while she received a light AA suite for the first time with the addition of six 54-caliber Breda 37 mm (1.5 in) guns in single mounts, a dozen 20 mm (0.79 in) Breda Model 35 autocannon in six twin mounts and four 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Breda Model 31 machine guns in two twin mounts.[20]

Prior to her being sent to reinforce the defences of Tobruk in early May 1940, a fifth 100/47 gun turret was added on the forecastle and five more twin 13.2 mm (0.52 in) machine gun mounts were added to better suit her new role as a floating battery.[21] Two days after Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June, the British launched a co-ordinated sea and land attack against Tobruk. The British naval force, including the light cruisers Gloucester and Liverpool bombarded the port and engaged San Giorgio, which suffered no damage,[22] while Royal Air Force Blenheim bombers from No. 45, No. 55, and No. 211 Squadrons[23] also attacked Tobruk, striking San Giorgio with a bomb.[24] On 19 June, the British submarine HMS Parthian fired two torpedoes at San Giorgio, but they detonated before hitting the ship.[25]

San Giorgio's main role was to supplement the anti-aircraft defences of Tobruk; between June 1940 and January 1941, she claimed 47 enemy aircraft shot down or damaged.[26][27] When Commonwealth troops surrounded Tobruk and prepared to storm it during Operation Compass, in January 1941, the ship was kept in port as it was thought that her main guns could be useful for halting, at least temporarily, the British tanks. Therefore, San Giorgio remained in Tobruk and participated in the defense of the town with her armament. The ship was seaworthy (she had been stationary since June 1940, but she was not immobilized), and when the fall of Tobruk appeared imminent the local naval commander Admiral Massimiliano Vietina requested authorization from the naval high command in Rome (Supermarina) for her to leave, so as to avoid what was perceived as the preventable loss of a perfectly sound, if outdated, cruiser; however, the Italian commander-in-chief in Libya, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, opposed San Giorgio's leaving, "…so as not to deprive the fortress of the contribution of San Giorgio’s guns and especially for moral reasons, since the departure of the ship would be harmful for the land troops' [morale] [if it were to happen] right at the moment the enemy attack is underway". The Italian Supreme Command decided that the ship should stay. Therefore, San Giorgio remained in Tobruk and kept firing on the attacking land forces throughout the battle, until the town had fallen. In the early hours of January 22, after the last resistance in Tobruk had ceased, the crew was disembarked and a small scuttling party, headed by Captain Stefano Pugliese, blew up her magazines so that she would not fall intact into British hands. Most of the crew, including the badly wounded Pugliese (who had been injured by the premature explosion of one of the scuttling charges), were taken prisoner, although a small party managed to escape to Italy in a fishing boat, carrying with them San Giorgio's war flag.[26][21] The ship was awarded the Gold Medal of Military Valor (Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare) for her actions in the defence of Tobruk.[28] Inspection of San Giorgio's torpedo nets, after the fall of Tobruk, revealed that as many as 39 torpedoes, most of them launched by British aircraft, had become stuck in the nets in her seven months of wartime service.[26]

San Giorgio's hulk was commissioned by the British in March 1943 as HMS San Giorgio for use as a stationary repair ship and was used by them for the rest of the war.[29] The wreck was refloated in 1952, but it sank en route to Italy.[21]

References

Notes

- ↑ Fraccaroli 1970, p. 33

- 1 2 3 Silverstone, p. 290

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gardiner & Gray, p. 261

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 305

- ↑ Hythe, pp. 49–50

- ↑ Beehler, p. 84 (online)

- ↑ Marchese

- ↑ "Admiral Cagni Dismissed: Cruiser San Giorgio's Captain Also Dropped for Recent Accident". New York Times. 12 December 1913. p. 1. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ Sondhaus, pp. 274–276, 279

- ↑ Halpern, pp. 148, 151; Sondhaus, p. 289

- ↑ Halpern, p. 176

- ↑ Fraccaroli 1976, p. 318

- ↑ "Prince Humbert Sails". The New York Times. 2 July 1924. p. 31.

- ↑ "Rebel City of Brazil is Bombarded". The Los Angeles Times. 18 July 1924. p. 1.

- ↑ "Buenas Aires Acclaims Humbert". The New York Times. 7 August 1924. p. 17.

- ↑ "Humbert Reviews Troops". The New York Times. 11 August 1924. p. 26.

- ↑ "Prince Humbert Sails for Italy". The New York Times. 6 September 1925. p. 14.

- ↑ "Humbert Sails Home from Brazil". The New York Times. 20 September 1924. p. 22.

- ↑ Sicurezza, p. 46

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray, p. 262

- 1 2 3 Brescia, p. 104

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 28

- ↑ Playfair, Vol. I, pp. 112–113

- ↑ Shores, Massimello & Guest, p. 24

- ↑ "HMS Parthian (N 75)". uboat.net. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Arremba San Zorzo

- ↑ Long, p. 230

- ↑ "San Giorgio: Incrociatore corazzato". Storia e Cultura: La nostra Storia: Almanacco storico navale (in Italian). Marina Militare. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Colledge, p. 305

Bibliography

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War, Sept. 29, 1911 to Oct. 18, 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Advertiser-Republican. OCLC 63576798.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Fraccarolli, Aldo (1976). "Question 14/76: Details of Italian Cruiser Brindisi". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization. XIII (4): 317–18.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Hythe, Viscount (1912). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth, UK: J. Griffin. OCLC 5973345.

- Long, Gavin (1961). To Benghazi. Australia in the War of 1939-1945: Series 1 (Army). Vol. I (2nd, corrected ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220664876.

- Marchese, Giuseppe (February 1996). "La Posta Militare della Marina Italiana 8^ puntata". La Posta Militare (in Italian) (72). Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn, Captain F.C. (R.N.) & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2009) [1st. pub. HMSO:1954]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume I: The Early Successes Against Italy, to May 1941. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-065-8.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Shores, Christopher, Giovanni Massimello & Russell Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War 1940–1945: Volume One: North Africa June 1940–January 1945. London: Grub Street, 2012. ISBN 978-1-90811-707-6.

- Sicurezza, Renato. "Il Regio Incrociatore Corazzato San Giorgio". Yacht World (in Italian). Milan: Scode: 44–47. ISSN 0394-3143.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9. OCLC 59919233.

External links

- San Giorgio in WWII on regiamarina.net

- San Giorgio (1908) Marina Militare website