| Poland during Jagiellonian dynasty | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1385–1572 | |||

| |||

| Monarch(s) |

| ||

Chronology

| |||

| History of Poland |

|---|

|

|

|

The rule of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Poland between 1386 and 1572 spans the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period in European history. The Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) founded the dynasty; his marriage to Queen Jadwiga of Poland[1] in 1386 strengthened an ongoing Polish–Lithuanian union. The partnership brought vast territories controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for both the Polish and Lithuanian people, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities in Europe for the next four centuries.[2][3]

In the Baltic Sea region, Poland engaged in ongoing conflict with the Teutonic Knights. The struggles led to a major battle, the Battle of Grunwald of 1410, but there was also the milestone Peace of Thorn of 1466 under King Casimir IV Jagiellon; the treaty defined the basis of the future Duchy of Prussia. In the south, Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars, and in the east Poles helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Poland's and Lithuania's territorial expansion included the far north region of Livonia.[2][3]

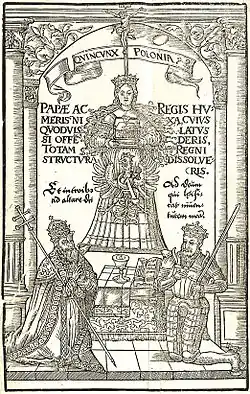

In the Jagiellonian period, Poland developed as a feudal state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant landed nobility. The Nihil novi act adopted by the Polish Sejm in 1505 transferred most of the legislative power in the state from the monarch to the Sejm. This event marked the beginning of the system known as the "Golden Liberty", when the "free and equal" members of the Polish nobility ruled the state[2][3] and elected the monarch.

The 16th century saw Protestant Reformation movements deeply influencing Polish Christianity, resulting in unique policies of religious tolerance for the Europe of that time. The European Renaissance as fostered by the last Jagiellonian Kings Sigismund I the Old (r. 1506–1548) and Sigismund II Augustus (r. 1548–1572) resulted in an immense cultural flowering.[2][3]

Late Middle Ages (14th–15th century)

Jagiellonian monarchy

In 1385, the Union of Krewo was signed between Queen Jadwiga of Poland and Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, the ruler of the last pagan state in Europe. The act arranged for Jogaila's baptism and the couple's marriage, which established the beginning of the Polish–Lithuanian union. After Jogaila's baptism, he was known in Poland by his baptismal name Władysław and the Polish version of his Lithuanian name, Jagiełło. The union strengthened both nations in their shared opposition to the Teutonic Knights and the growing threat of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[4]

Vast expanses of Rus' lands, including the Dnieper River basin and territories extending south to the Black Sea, were at that time under Lithuanian control. In order to gain control of these vast holdings, Lithuanians and Ruthenians had fought the Battle of Blue Waters in 1362 or 1363 against the invading Mongols and had taken advantage of the power vacuum to the south and east that resulted from the Mongol destruction of Kievan Rus'. The population of the Grand Duchy's enlarged territory was accordingly heavily Ruthenian and Eastern Orthodox. The territorial expansion led to a confrontation between Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow, which found itself emerging from the Tatar rule and itself in a process of expansion.[5] Uniquely in Europe, the union connected two states geographically located on the opposite sides of the great civilizational divide between the Western Christian or Latin world, and the Eastern Christian or Byzantine world.[6]

The intention of the union was to create a common state under Władysław Jagiełło, but the ruling oligarchy of Poland learned that their goal of incorporating Lithuania into Poland was unrealistic. Territorial disputes led to warfare between Poland and Lithuania or Lithuanian factions; the Lithuanians at times even found it expedient to conspire with the Teutonic Knights against the Poles.[7] Geographic consequences of the dynastic union and the preferences of the Jagiellonian kings instead created a process of orientating Polish territorial priorities to the east.[4]

Between 1386 and 1572, the Polish–Lithuanian union was ruled by a succession of constitutional monarchs of the Jagiellonian dynasty. The political influence of the Jagiellonian kings gradually diminished during this period, while the landed nobility took over an ever-increasing role in central government and national affairs.[a] The royal dynasty, however, had a stabilizing effect on Poland's politics. The Jagiellonian Era is often regarded as a period of maximum political power, great prosperity, and in its later stage, a Golden Age of Polish culture.[4]

Social and economic developments

The feudal rent system prevalent in the 13th and 14th centuries, under which each estate had well defined rights and obligations, degenerated around the 15th century as the nobility tightened their control over manufacturing, trade and other economic activities. This created many directly owned agricultural enterprises known as folwarks in which feudal rent payments were replaced with forced labor on the lord's land. This limited the rights of cities and forced most of the peasants into serfdom.[8] Such practices were increasingly sanctioned by the law. For example, the Piotrków Privilege of 1496, granted by King John I Albert, banned rural land purchases by townspeople and severely limited the ability of peasant farmers to leave their villages. Polish towns, lacking national representation protecting their class interests, preserved some degree of self-government (city councils and jury courts), and the trades were able to organize and form guilds. The nobility soon excused themselves from their principal duty: mandatory military service in case of war (pospolite ruszenie). The division of the nobility into two main layers was institutionalized, but never legally formalized, in the Nihil novi "constitution" of 1505, which required the king to consult the general sejm, that is the Senate, as well as the lower chamber of (regional) deputies, the Sejm proper, before enacting any changes. The masses of ordinary nobles szlachta competed or tried to compete against the uppermost rank of their class, the magnates, for the duration of Poland's independent existence.[9]

Poland and Lithuania in personal union under Jagiełło

The first king of the new dynasty was Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, who was known as Władysław II Jagiełło in Poland. He was elected king of Poland in 1386 after his marriage to Jadwiga of Anjou, the King of Poland in her own right, and his conversion to Catholicism. The Christianization of Lithuania into the Latin Church followed. Jogaila's rivalry in Lithuania with his cousin Vytautas the Great, who was opposed to Lithuania's domination by Poland,[10] was settled in 1392 in the Ostrów Agreement and in 1401 in the Union of Vilnius and Radom: Vytautas became the Grand Duke of Lithuania for life under Jogaila's nominal supremacy. The agreement made possible a close cooperation between the two nations necessary to succeed in struggles with the Teutonic Order. The Union of Horodło of 1413 defined the relationship further and granted privileges to the Roman Catholic (as opposed to Eastern Orthodox) segment of the Lithuanian nobility.[11][12]

Struggle with the Teutonic Knights

The Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War of 1409–1411, precipitated by the Samogitian uprisings in Lithuanian territories controlled by the State of the Teutonic Order, culminated in the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg), in which the combined forces of the Polish and Lithuanian-Rus' armies completely defeated the Teutonic Knights. The offensive that followed lost its impact with the ineffective siege of Malbork (Marienburg). The failure to take the fortress and eliminate the Teutonic (later Prussian) state had dire historic consequences for Poland in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. The Peace of Thorn of 1411 gave Poland and Lithuania rather modest territorial adjustments, including Samogitia. Afterwards, there were more military campaigns and peace deals that did not hold. One unresolved arbitration took place at the Council of Constance. In 1415, Paulus Vladimiri, rector of the Kraków Academy, presented his Treatise on the Power of the Pope and the Emperor in respect to Infidels at the council, in which he advocated tolerance, criticized the violent conversion methods of the Teutonic Knights, and postulated that pagans have the right to peaceful coexistence with Christians and political independence. This stage of the Polish-Lithuanian conflict with the Teutonic Order ended with the Treaty of Melno in 1422. The Polish-Teutonic War of 1431-35 (see Battle of Wiłkomierz) was concluded with the Peace of Brześć Kujawski in 1435.[13]

The Hussite movement and the Polish–Hungarian union

During the Hussite Wars of 1420–1434, Jagiełło, Vytautas and Sigismund Korybut were involved in political and military intrigues with respect to the Czech crown, which was offered by the Hussites to Jagiełło in 1420. Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki became known as the leading opponent of a union with the Hussite Czech state.[14]

The Jagiellonian dynasty was not entitled to automatic hereditary succession, rather each new king had to be approved by nobility consensus. Władysław Jagiełło had two sons late in life from his last wife Sophia of Halshany. In 1430, the nobility agreed to the succession of the future Władysław III only after the king consented to a series of concessions. In 1434, the old monarch died and his minor son Władysław was crowned; the Royal Council led by Bishop Oleśnicki undertook the regency duties.[14]

In 1438, the Czech anti-Habsburg opposition, mainly Hussite factions, offered the Czech crown to Jagiełło's younger son Casimir. The idea, accepted in Poland over Oleśnicki's objections, resulted in two unsuccessful Polish military expeditions to Bohemia.[14]

After Vytautas' death in 1430, Lithuania became embroiled in internal wars and conflicts with Poland. Casimir, sent as a boy by King Władysław on a mission there in 1440, was surprisingly proclaimed by the Lithuanians as their Grand Duke, and he remained in Lithuania.[14]

Oleśnicki gained the upper hand again and pursued his long-term objective of Poland's union with Hungary. At that time, the Ottoman Empire embarked on a fresh round of European conquests and threatened Hungary, which needed the assistance of the powerful Polish–Lithuanian ally. In 1440, Władysław III assumed the Hungarian throne. Influenced by Julian Cesarini, the young king led the Hungarian army against the Ottomans in 1443 and again in 1444. Like Cesarini, Władysław III was killed at the Battle of Varna.[14]

Beginning near the end of Jagiełło's life, Poland was governed in practice by an oligarchy of magnates led by Bishop Oleśnicki. The rule of the dignitaries was actively opposed by various groups of szlachta. Their leader Spytek of Melsztyn was killed at the Battle of Grotniki in 1439, which allowed Oleśnicki to purge Poland of the remaining Hussite sympathizers and pursue his other objectives without significant opposition.[14]

The accession of Casimir IV Jagiellon

In 1445, Casimir, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, was asked to assume the Polish throne vacated upon the death of his brother Władysław. Casimir was a tough negotiator and did not accept the Polish nobility's conditions for his election. He finally arrived in Poland and was crowned in 1447 on his own terms. His assumption of the Crown of Poland freed Casimir from the control that the Lithuanian oligarchy had imposed on him; in the Vilnius Privilege of 1447, he declared the Lithuanian nobility to have equal rights with Polish szlachta. In time, Casimir was able to wrest power from Cardinal Oleśnicki and his group. He replaced their influence with a power base built on the younger middle nobility. Casimir was able to resolve a conflict with the pope and the local Church hierarchy over the right to fill vacant bishop positions in his favor.[15]

War with the Teutonic Order and its resolution

In 1454, the Prussian Confederation, an alliance of Prussian cities and nobility opposed to the increasingly oppressive rule of the Teutonic Knights, asked King Casimir to take over Prussia and initiated an armed uprising against the Knights. Casimir declared a war on the Order and the formal incorporation of Prussia into the Polish Crown; those events led to the Thirteen Years' War of 1454–66. The mobilization of the Polish forces (the pospolite ruszenie) was weak at first, since the szlachta would not cooperate without concessions from Casimir that were formalized in the Statutes of Nieszawa promulgated in 1454. This prevented a takeover of all of Prussia, but in the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466, the Knights had to surrender the western half of their territory to the Polish Crown (the areas known afterwards as Royal Prussia, a semi-autonomous entity), and to accept Polish-Lithuanian suzerainty over the remainder (the later Ducal Prussia). Poland regained Pomerelia, with its access to the Baltic Sea, as well as Warmia. In addition to land warfare, naval battles took place in which ships provided by the City of Danzig (Gdańsk) successfully fought Danish and Teutonic fleets.[16]

Other territories recovered by the Polish Crown in the 15th-century include the Duchy of Oświęcim and Duchy of Zator on Silesia's border with Lesser Poland, and there was notable progress regarding the incorporation of the Piast Masovian duchies into the Crown.[16]

Turkish and Tatar wars

The influence of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Central Europe rose during the 15th century. In 1471, Casimir's son Władysław became king of Bohemia, and in 1490, also of Hungary.[16] The southern and eastern outskirts of Poland and Lithuania became threatened by Turkish invasions beginning in the late 15th century. Moldavia's involvement with Poland goes back to 1387, when Petru I, Hospodar of Moldavia sought protection against the Hungarians by paying homage to King Władysław II Jagiełło in Lviv. This move gave Poland access to Black Sea ports.[17] In 1485, King Casimir undertook an expedition into Moldavia after its seaports were overtaken by the Ottoman Turks. The Turkish-controlled Crimean Tatars raided the eastern territories in 1482 and 1487 until they were confronted by King John Albert, Casimir's son and successor.

Poland was attacked in 1487–1491 by remnants of the Golden Horde that invaded Poland as far as Lublin before being beaten at Zaslavl.[18] In 1497, King John Albert made an attempt to resolve the Turkish problem militarily, but his efforts were unsuccessful; he was unable to secure effective participation in the war by his brothers, King Vladislas (Władysław) II of Bohemia and Hungary and Alexander, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and he also faced resistance on the part of Stephen the Great, the ruler of Moldavia. More destructive Tatar raids instigated by the Ottoman Empire took place in 1498, 1499 and 1500.[19] Diplomatic peace efforts initiated by John Albert were finalized after the king's death in 1503. They resulted in a territorial compromise and an unstable truce.[20]

Invasions into Poland and Lithuania from the Crimean Khanate took place in 1502 and 1506 during the reign of King Alexander. In 1506, the Tatars were defeated at the Battle of Kletsk by Michael Glinski.[21]

Moscow's threat to Lithuania; accession of Sigismund I

Lithuania was increasingly threatened by the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow in the 15th and 16th centuries. Moscow indeed took over many of Lithuania's eastern possessions in military campaigns of 1471, 1492, and 1500. Grand Duke Alexander of Lithuania was elected King of Poland in 1501, after the death of John Albert. In 1506, he was succeeded by Sigismund I the Old (Zygmunt I Stary) in both Poland and Lithuania as political realities were drawing the two states closer together. Prior to his accession to the Polish throne, Sigismund had been a Duke of Silesia by the authority of his brother Vladislas II of Bohemia, but like other Jagiellon rulers before him, he did not pursue the claim of the Polish Crown to Silesia.[22]

Culture in the Late Middle Ages

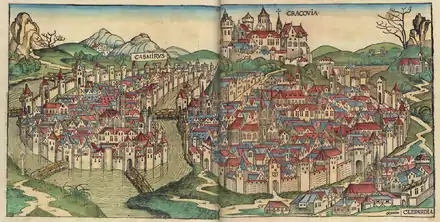

The culture of the 15th century Poland can be described as retaining typical medieval characteristics. Nonetheless, the crafts and industries in existence already in the preceding centuries became more highly developed under favorable social and economic conditions, and their products were much more widely disseminated. Paper production was one of the new industries that appeared, and printing developed during the last quarter of the century. In 1473, Kasper Straube produced the first Latin print in Kraków, whereas Kasper Elyan printed Polish texts for the first time in Wrocław (Breslau) in 1475. The world's oldest prints in Cyrillic script, namely religious texts in Old Church Slavonic, appeared after 1490 from the press of Schweipolt Fiol in Krakow.[23][24]

Luxury items were in high demand among the increasingly prosperous nobility, and to a lesser degree among the wealthy town merchants. Brick and stone residential buildings became common, but only in cities. The mature Gothic style was represented not only in architecture, but also in sacral wooden sculpture. The Altar of Veit Stoss in St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków is one of the most magnificent art works of its kind in Europe.[23]

Kraków University, which stopped functioning after the death of Casimir the Great, was renewed and rejuvenated around 1400. Augmented by a theology department, the "academy" was supported and protected by Queen Jadwiga and the Jagiellonian dynasty members, which is reflected in its present name: the Jagiellonian University. Europe's oldest department of mathematics and astronomy was established in 1405. Among the university's prominent scholars were Stanisław of Skarbimierz, Paulus Vladimiri and Albert of Brudzewo, Copernicus' teacher.[23]

John of Ludzisko and Archbishop Gregory of Sanok, the precursors of Polish humanism, were professors at the university. Gregory's court was the site of an early literary society at Lwów (Lviv) after he became the archbishop there. Scholarly thought elsewhere was represented by Jan Ostroróg, a political publicist and reformist, and Jan Długosz, a historian, whose Annals is the largest history work of his time in Europe and a fundamental source for history of medieval Poland. Distinguished and influential foreign humanists were also active in Poland. Filippo Buonaccorsi, a poet and diplomat, arrived from Italy in 1468 and stayed in Poland until his death in 1496. Known as Kallimach, he prepared biographies of Gregory of Sanok, Zbigniew Oleśnicki, and very likely Jan Długosz, besides establishing another literary society in Kraków. He tutored and mentored the sons of Casimir IV and postulated unrestrained royal power. In Kraków, the German humanist Conrad Celtes organized the humanist literary and scholarly association Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana, the first in this part of Europe.[23]

Early Modern Era (16th century)

Agriculture-based economic expansion

The folwark, a large-scale system of agricultural production based on serfdom, was a dominant feature on Poland's economic landscape beginning in the late 15th century and for the next 300 years. This dependence on nobility-controlled agriculture in central-eastern Europe diverged from the western part of the continent, where elements of capitalism and industrialization were developing to a much greater extent, with the attendant growth of a bourgeoisie class and its political influence. The 16th-century agricultural trade boom combined with free or very cheap peasant labor made the folwark economy very profitable.[25]

.jpg.webp)

Mining and metallurgy developed further during the 16th century, and technical progress took place in various commercial applications. Great quantities of exported agricultural and forest products floated down the rivers to be transported through ports and land routes. This resulted in a positive trade balance for Poland throughout the 16th century. Imports from the West included industrial products, luxury products and fabrics.[26]

Most of the exported grain left Poland through Gdańsk (Danzig), which became the wealthiest, most highly developed, and most autonomous of the Polish cities because of its location at the mouth of the Vistula River and access to the Baltic Sea. It was also by far the largest center for manufacturing. Other towns were negatively affected by Gdańsk's near-monopoly in foreign trade, but profitably participated in transit and export activities. The largest of those were Kraków (Cracow), Poznań, Lwów (Lviv), and Warszawa (Warsaw), and outside of the Crown, Breslau (Wrocław). Thorn (Toruń) and Elbing (Elbląg) were the main cities in Royal Prussia after Gdańsk.[26][27]

Burghers and nobles

During the 16th century, prosperous patrician families of merchants, bankers, or industrial investors, many of German origin, still conducted large-scale business operations in Europe or lent money to Polish noble interests, including the royal court. Some regions were highly urbanized in comparison to most of the rest of Europe. In Greater Poland and Lesser Poland at the end of the 16th century, for example, 30% of the population lived in cities.[28] 256 towns were founded, most in Red Ruthenia.[b] The townspeople's upper layer was ethnically multinational and tended to be well-educated. Numerous sons of burghers studied at the Academy of Kraków and at foreign universities; members of their group are among the finest contributors to the culture of the Polish Renaissance. Unable to form their own nationwide political class, many blended into the nobility in spite of the legal obstacles.[28]

The nobility (or szlachta) in Poland constituted a greater proportion of the population than in other countries, up to 10%. In principle, they were all equal and politically empowered, but some had no property and were not allowed to hold offices or participate in sejms or sejmiks, the legislative bodies. Of the "landed" nobility, some possessed a small patch of land that they tended themselves and lived like peasant families, while the magnates owned dukedom-like networks of estates with several hundred towns and villages and many thousands of subjects. Mixed marriages gave some peasants one of the few possible paths to nobility.

16th-century Poland was officially a "republic of nobles", and the "middle class" of the nobility (individuals at a lower social level than "magnates") formed the leading component during the later Jagiellonian period and afterwards. Nonetheless, members of the magnate families held the highest state and church offices. At that time, the szlachta in Poland and Lithuania was ethnically diversified and represented several religious denominations. During this period of tolerance, such factors had little bearing on one's economic status or career potential. Jealous of their class privilege ("freedoms"), the Renaissance szlachta developed a sense of public service duties, educated their youth, took keen interest in current trends and affairs and traveled widely. The Golden Age of Polish Culture adopted western humanism and Renaissance patterns, and visiting foreigners often remarked on the splendor of their residencies and the conspicuous consumption of wealthy Polish nobles.[28]

Reformation

In a situation analogous with that of other European countries, the progressive internal decay of the Polish Church created conditions favorable for the dissemination of the Reformation ideas and currents. For example, there was a chasm between the lower clergy and the nobility-based Church hierarchy, which was quite laicized and preoccupied with temporal issues, such as power and wealth, and often corrupt. The middle nobility, which had already been exposed to the Hussite reformist persuasion, increasingly looked at the Church's many privileges with envy and hostility.[29]

The teachings of Martin Luther were accepted most readily in the regions with strong German connections: Silesia, Greater Poland, Pomerania and Prussia. In Gdańsk (Danzig) in 1525 a lower-class Lutheran social uprising took place and was bloodily subdued by Sigismund I; after the reckoning he established a representation for the plebeian interests as a segment of the city government. Königsberg and the Duchy of Prussia under Albrecht Hohenzollern became a strong center of Protestant propaganda dissemination affecting all of northern Poland and Lithuania. Sigismund quickly reacted against the "religious novelties", issuing his first related edict in 1520, banning any promotion of the Lutheran ideology, or even foreign trips to the Lutheran centers. Such attempted (poorly enforced) prohibitions continued until 1543.[29]

.jpg.webp)

Sigismund's son Sigismund II Augustus (Zygmunt II August), a monarch of a much more tolerant attitude, guaranteed the freedom of the Lutheran religion practice in all of Royal Prussia by 1559. Besides Lutheranism, which, within the Polish Crown, ultimately found substantial following mainly in the cities of Royal Prussia and western Greater Poland, the teachings of the persecuted Anabaptists and Unitarians, and in Greater Poland the Czech Brothers, were met, at least among the szlachta, with a more sporadic response.[29]

In Royal Prussia, 41% of the parishes were counted as Lutheran in the second half of the 16th century, but that percentage kept increasing. According to Kasper Cichocki, who wrote in the early 17th century, only remnants of Catholicism were left there in his time. Lutheranism was strongly dominant in Royal Prussia throughout the 17th century, with the exception of Warmia (Ermland).[30]

.jpg.webp)

Around 1570, of the at least 700 Protestant congregations in Poland–Lithuania, over 420 were Calvinist and over 140 Lutheran, with the latter including 30-40 ethnically Polish. Protestants encompassed approximately ½ of the magnate class, ¼ of other nobility and townspeople, and 1/20 of the non-Orthodox peasantry. The bulk of the Polish-speaking population had remained Catholic, but the proportion of Catholics became significantly diminished within the upper social ranks.[30]

Calvinism gained many followers in the mid 16th century among both the szlachta and the magnates, especially in Lesser Poland and Lithuania. The Calvinists, who led by Jan Łaski were working on unification of the Protestant churches, proposed the establishment of a Polish national church, under which all Christian denominations, including Eastern Orthodox (very numerous in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Ukraine), would be united. After 1555 Sigismund II, who accepted their ideas, sent an envoy to the pope, but the papacy rejected the various Calvinist postulates. Łaski and several other Calvinist scholars published in 1563 the Bible of Brest, a complete Polish Bible translation from the original languages, an undertaking financed by Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black.[31] After 1563–1565 (the abolishment of state enforcement of the Church jurisdiction), full religious tolerance became the norm. The Polish Catholic Church emerged from this critical period weakened but not badly damaged (the bulk of the Church property was preserved), which facilitated the later success of Counter-Reformation.[29]

Among the Calvinists, who also included the lower classes and their leaders, ministers of common background, disagreements soon developed, based on different views in the areas of religious and social doctrines. The official split took place in 1562, when two separate churches were officially established: the mainstream Calvinist and the smaller, more reformist, Polish Brethren or Arians. The adherents of the radical wing of the Polish Brethren promoted, often by way of personal example, the ideas of social justice. Many Arians (such as Piotr of Goniądz and Jan Niemojewski) were pacifists opposed to private property, serfdom, state authority and military service; through communal living some had implemented the ideas of shared usage of the land and other property. A major Polish Brethren congregation and center of activities was established in 1569 in Raków near Kielce, and lasted until 1638, when Counter-Reformation had it closed.[32] The notable Sandomierz Agreement of 1570, an act of compromise and cooperation among several Polish Protestant denominations, excluded the Arians, whose more moderate, larger faction toward the end of the century gained the upper hand within the movement.[29]

The act of the Warsaw Confederation, which took place during the convocation sejm of 1573, provided guarantees, at least for the nobility, of religious freedom and peace. It gave the Protestant denominations, including the Polish Brethren, formal rights for many decades to come. Uniquely in 16th-century Europe, it turned the Commonwealth, in the words of Cardinal Stanislaus Hosius, a Catholic reformer, into a "safe haven for heretics".[29]

Culture of Polish Renaissance

Golden Age of Polish culture

The Polish "Golden Age", the period of the reigns of Sigismund I and Sigismund II, the last two Jagiellonian kings, or more generally the 16th century, is most often identified with the rise of the culture of Polish Renaissance. The cultural flowering had its material base in the prosperity of the elites, both the landed nobility and urban patriciate at such centers as Kraków and Gdańsk.[33] As was the case with other European nations, the Renaissance inspiration came in the first place from Italy, a process accelerated to some degree by Sigismund I's marriage to Bona Sforza.[33] Many Poles traveled to Italy to study and to learn its culture. As imitating Italian ways became very trendy (the royal courts of the two kings provided the leadership and example for everybody else), many Italian artists and thinkers were coming to Poland, some settling and working there for many years. While the pioneering Polish humanists, greatly influenced by Erasmus of Rotterdam, accomplished the preliminary assimilation of the antiquity culture, the generation that followed was able to put greater emphasis on the development of native elements, and because of its social diversity, advanced the process of national integration.[34]

Literacy, education and patronage of intellectual endeavors

Beginning in 1473 in Cracow (Kraków), the printing business kept growing. By the turn of the 16th/17th century there were about 20 printing houses within the Commonwealth, 8 in Cracow, the rest mostly in Gdańsk (Danzig), Thorn (Toruń) and Zamość. The Academy of Kraków and Sigismund II possessed well-stocked libraries; smaller collections were increasingly common at noble courts, schools and townspeople's households. Illiteracy levels were falling, as by the end of the 16th century almost every parish ran a school.[35]

The Lubrański Academy, an institution of higher learning, was established in Poznań in 1519. The Reformation resulted in the establishment of a number of gymnasiums, academically oriented secondary schools, some of international renown, as the Protestant denominations wanted to attract supporters by offering high quality education. The Catholic reaction was the creation of Jesuit colleges of comparable quality. The Kraków University in turn responded with humanist program gymnasiums of its own.[35]

The university itself experienced a period of prominence at the turn of the 15th/16th century, when especially the mathematics, astronomy and geography faculties attracted numerous students from abroad. Latin, Greek, Hebrew and their literatures were likewise popular. By the mid 16th century the institution entered a crisis stage, and by the early 17th century regressed into Counter-reformational conformism. The Jesuits took advantage of the infighting and established in 1579 a university college in Vilnius, but their efforts aimed at taking over the Academy of Kraków were unsuccessful. Under the circumstances many elected to pursue their studies abroad.[35]

Sigismund I the Old, who built the presently existing Wawel Renaissance castle, and his son Sigismund II Augustus, supported intellectual and artistic activities and surrounded themselves with the creative elite. Their patronage example was followed by ecclesiastic and lay feudal lords, and by patricians in major towns.[35]

Science

Polish science reached its culmination in the first half of the 16th century, in which the medieval point of view was criticized and more rational explanations were formulated. Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, published in Nuremberg in 1543, shook up the traditional value system extended into an understanding of the physical universe, doing away with its Christianity-adopted Ptolemaic anthropocentric model and setting free the explosion of scientific inquiry. Generally the prominent scientists of the period resided in many different regions of the country, and increasingly, the majority were of urban, rather than noble origin.[36]

Nicolaus Copernicus, a son of a Toruń trader from Kraków, made many contributions to science and the arts. His scientific creativity was inspired at the University of Kraków, at the institution's height; he also studied at Italian universities later. Copernicus wrote Latin poetry, developed an economic theory, functioned as a cleric-administrator, political activist in Prussian sejmiks, and led the defense of Olsztyn against the forces of Albrecht Hohenzollern. As an astronomer, he worked on his scientific theory for many years at Frombork, where he died.[36]

Josephus Struthius became famous as a physician and medical researcher. Bernard Wapowski was a pioneer of Polish cartography. Maciej Miechowita, a rector at the Cracow Academy, published in 1517 Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis, a treatise on the geography of the East, an area in which Polish investigators provided first-hand expertise for the rest of Europe.[36]

Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski was one of the greatest theorists of political thought in Renaissance Europe. His most famous work, On the Improvement of the Commonwealth, was published in Kraków in 1551. Modrzewski criticized the feudal societal relations and proposed broad realistic reforms. He postulated that all social classes should be subjected to the law to the same degree, and wanted to moderate the existing inequities. Modrzewski, an influential and often translated author, was a passionate proponent of the peaceful resolution of international conflicts.[36] Bishop Wawrzyniec Goślicki (Goslicius), who wrote and published in 1568 a study entitled De optimo senatore (The Counsellor in the 1598 English translation), was another popular and influential in the West political thinker.[37]

Historian Marcin Kromer wrote De origine et rebus gestis Polonorum (On the origin and deeds of Poles) in 1555 and in 1577 Polonia, a treatise highly regarded in Europe. Marcin Bielski's Chronicle of the Whole World, a universal history, was written ca. 1550. The chronicle of Maciej Stryjkowski (1582) covered the history of Eastern Europe.[36]

Literature

Modern Polish literature begins in the 16th century. At that time the Polish language, common to all educated groups, matured and penetrated all areas of public life, including municipal institutions, the legal code, the Church, and other official uses, coexisting for a while with Latin. Klemens Janicki, one of the Renaissance Latin language poets and a laureate of a papal distinction, was of peasant origin. Another plebeian author, Biernat of Lublin, wrote his own version of Aesop's fables in Polish, permeated with his socially radical views.[38]

A Literary Polish language breakthrough came under the influence of the Reformation with the writings of Mikołaj Rej. In his Brief Discourse, a satire published in 1543, he defends a serf from a priest and a noble, but in his later works he often celebrates the joys of the peaceful but privileged life of a country gentleman. Rej, whose legacy is his unbashful promotion of the Polish language, left a great variety of literary pieces. Łukasz Górnicki, an author and translator, perfected the Polish prose of the period. His contemporary and friend Jan Kochanowski became one of the greatest Polish poets of all time.[38]

Kochanowski was born in 1530 into a prosperous noble family. In his youth he studied at the universities of Kraków, Königsberg and Padua and traveled extensively in Europe. He worked for a time as a royal secretary, and then settled in the village of Czarnolas, a part of his family inheritance. Kochanowski's multifaceted creative output is remarkable for both the depth of thoughts and feelings that he shares with the reader, and for its beauty and classic perfection of form. Among Kochanowski's best known works are bucolic Frascas (trifles), epic poetry, religious lyrics, drama-tragedy The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, and the most highly regarded Threnodies or laments, written after the death of his young daughter.[38]

The poet Mikołaj Sęp Szarzyński, an intellectually refined master of small forms, bridges the late Renaissance and early Baroque artistic periods.[38]

Music

Following the European and Italian in particular musical trends, the Renaissance music was developing in Poland, centered around the royal court patronage and branching from there. Sigismund I kept from 1543 a permanent choir at the Wawel castle, while the Reformation brought large scale group Polish language church singing during the services. Jan of Lublin wrote a comprehensive tablature for the organ and other keyboard instruments.[39] Among the composers, who often permeated their music with national and folk elements, were Wacław of Szamotuły, Mikołaj Gomółka, who wrote music to Kochanowski translated psalms, and Mikołaj Zieleński, who enriched the Polish music by adopting the Venetian School polyphonic style.[40]

Architecture, sculpture and painting

Architecture, sculpture and painting developed also under Italian influence from the beginning of the 16th century. A number of professionals from Tuscany arrived and worked as royal artists in Kraków. Francesco Fiorentino worked on the tomb of John Albert already from 1502, and then together with Bartolommeo Berrecci and Benedykt from Sandomierz rebuilt the royal castle, which was accomplished between 1507 and 1536. Berrecci also built Sigismund's Chapel at Wawel Cathedral. Polish magnates, Silesian Piast princes in Brzeg, and even Kraków merchants (by the mid 16th century their class economically gained strength nationwide) built or rebuilt their residencies to make them resemble the Wawel Castle. Kraków's Sukiennice and Poznań City Hall are among numerous buildings rebuilt in the Renaissance manner, but Gothic construction continued alongside for a number of decades.[41]

Between 1580 and 1600 Jan Zamoyski commissioned the Venetian architect Bernardo Morando to build the city of Zamość. The town and its fortifications were designed to consistently implement the Renaissance and Mannerism aesthetic paradigms.[41]

Tombstone sculpture, often inside churches, is richly represented on graves of clergy and lay dignitaries and other wealthy individuals. Jan Maria Padovano and Jan Michałowicz of Urzędów count among the prominent artists.[41]

Painted illuminations in Balthasar Behem Codex are of exceptional quality, but draw their inspiration largely from Gothic art. Stanisław Samostrzelnik, a monk in the Cistercian monastery in Mogiła near Kraków, painted miniatures and polychromed wall frescos.[41]

Republic of middle nobility; execution movement

The Polish political system in the 16th century was contested terrain as the middle gentry (szlachta) sought power. Kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus manipulated political institutions to block the gentry. The kings used their appointment power and influence on the elections to the Sejm. They issued propaganda upholding the royal position and provided financing to favoured leaders of the gentry. Seldom did the kings resort to repression or violence. Compromises were reached so that in the second half of the 16th century—for the only time in Polish history—the "democracy of the gentry" was implemented.[42]

During the reign of Sigismund I, szlachta in the lower chamber of general sejm (from 1493 a bicameral legislative body), initially decidedly outnumbered by their more privileged colleagues from the senate (which is what the appointed for life prelates and barons of the royal council were being called now),[43] acquired a more numerous and fully elected representation. Sigismund however preferred to rule with the help of the magnates, pushing szlachta into the "opposition".[44]

After the Nihil novi act of 1505, a collection of laws known as Łaski's Statutes was published in 1506 and distributed to Polish courts. The legal pronouncements, intended to facilitate the functioning of a uniform and centralized state, with ordinary szlachta privileges strongly protected, were frequently ignored by the kings, beginning with Sigismund I, and the upper nobility or church interests. This situation became the basis for the formation around 1520 of the szlachta's execution movement, for the complete codification and execution, or enforcement, of the laws.[44]

%253B_A-7%253B_PL-MA%252C_Krak%C3%B3w%252C_Wawel.jpg.webp)

In 1518 Sigismund I married Bona Sforza d'Aragona, a young, strong-minded Italian princess. Bona's sway over the king and the magnates, her efforts to strengthen the monarch's political position, financial situation, and especially the measures she took to advance her personal and dynastic interests, including the forced royal election of the minor Sigismund Augustus in 1529 and his premature coronation in 1530, increased the discontent among szlachta activists.[44]

The opposition middle szlachta movement came up with a constructive reform program during the Kraków sejm of 1538/1539. Among the movement's demands were termination of the kings' practice of alienation of royal domain, giving or selling land estates to great lords at the monarch' discretion, and a ban on concurrent holding of multiple state offices by the same person, both legislated initially in 1504.[45] Sigismund I's unwillingness to move toward the implementation of the reformers' goals negatively affected the country's financial and defensive capabilities.[44]

The relationship with szlachta had only gotten worse during the early years of the reign of Sigismund II Augustus and remained bad until 1562. Sigismund Augustus' secret marriage with Barbara Radziwiłł in 1547, before his accession to the throne, was strongly opposed by his mother Bona and by the magnates of the Crown. Sigismund, who took over the reign after his father's death in 1548, overcame the resistance and had Barbara crowned in 1550; a few months later the new queen died. Bona, estranged from her son returned to Italy in 1556, where she died soon afterwards.[44]

The Sejm, until 1573 summoned by the king at his discretion (for example when he needed funds to wage a war), composed of the two chambers presided over by the monarch, became in the course of the 16th century the main organ of the state power. The reform-minded execution movement had its chance to take on the magnates and the church hierarchy (and take steps to restrain their abuse of power and wealth) when Sigismund Augustus switched sides and lent them his support at the sejm of 1562. During this and several more sessions of parliament, within the next decade or so, the Reformation inspired szlachta was able to push through a variety of reforms, which resulted in a fiscally more sound, better governed, more centralized and territorially unified Polish state. Some of the changes were too modest, other had never become completely implemented (e. g. recovery of the usurped Crown land), but nevertheless for the time being the middle szlachta movement was victorious.[44]

Mikołaj Sienicki, a Protestant activist, was a parliamentary leader of the execution movement and one of the organizers of the Warsaw Confederation.[44]

Resources and strategic objectives

Despite the favorable economic development, the military potential of 16th century Poland was modest in relation to the challenges and threats coming from several directions, which included the Ottoman Empire, the Teutonic state, the Habsburgs, and Muscovy. Given the declining military value and willingness of pospolite ruszenie, the bulk of the forces available consisted of professional and mercenary soldiers. Their number and provision depended on szlachta-approved funding (self-imposed taxation and other sources) and tended to be insufficient for any combination of adversaries. The quality of the forces and their command was good, as demonstrated by victories against a seemingly overwhelming enemy. The attainment of strategic objectives was supported by a well-developed service of knowledgeable diplomats and emissaries. Because of the limited resources at the state's disposal, the Jagiellonian Poland had to concentrate on the area most crucial for its security and economic interests, which was the strengthening of Poland's position along the Baltic coast.[46]

Prussia; struggle for Baltic area domination

.jpg.webp)

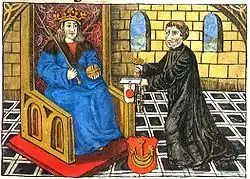

The Peace of Thorn of 1466 reduced the Teutonic Knights, but brought no lasting solution to the problem they presented for Poland and their state avoided paying the prescribed tribute.[47] The chronically difficult relations had gotten worse after the 1511 election of Albrecht as Grand Master of the Order. Faced with Albrecht's rearmament and hostile alliances, Poland waged a war in 1519; the war ended in 1521, when mediation by Charles V resulted in a truce. As a compromise move Albrecht, persuaded by Martin Luther, initiated a process of secularization of the Order and the establishment of a lay duchy of Prussia, as Poland's dependency, ruled by Albrecht and afterwards by his descendants. The terms of the proposed pact immediately improved Poland's Baltic region situation, and at that time also appeared to protect the country's long-term interests. The treaty was concluded in 1525 in Kraków; the remaining state of the Teutonic Knights (East Prussia centered on Königsberg) was converted into the Protestant (Lutheran) Duchy of Prussia under the King of Poland and the homage act of the new Prussian duke in Kraków followed.[48]

In reality the House of Hohenzollern, of which Albrecht was a member, the ruling family of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, had been actively expanding its territorial influence; for example already in the 16th century in Farther Pomerania and Silesia. Motivated by a current political expediency, Sigismund Augustus in 1563 allowed the Brandenburg elector branch of the Hohenzollerns, excluded under the 1525 agreement,[49] to inherit the Prussian fief rule. The decision, confirmed by the 1569 sejm, made the future union of Prussia with Brandenburg possible. Sigismind II, unlike his successors, was however careful to assert his supremacy. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, ruled after 1572 by elective kings, was even less able to counteract the growing importance of the dynastically active Hohenzollerns.[48]

In 1568 Sigismund Augustus, who had already embarked on a war fleet enlargement program, established the Maritime Commission. A conflict with the City of Gdańsk (Danzig), which felt that its monopolistic trade position was threatened, ensued. In 1569 Royal Prussia had its legal autonomy largely taken away, and in 1570 Poland's supremacy over Danzig and the Polish King's authority over the Baltic shipping trade were regulated and received statutory recognition (Karnkowski's Statutes).[50]

Wars with Moscow

%252C_Bitwa_pod_Orsz%C4%85.jpg.webp)

In the 16th century the Grand Duchy of Moscow continued activities aimed at unifying the old Rus' lands still under Lithuanian rule. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania had insufficient resources to counter Moscow's advances, already having to control the Rus' population within its borders and not being able to count on loyalty of Rus' feudal lords. As a result of the protracted war at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, Moscow acquired large tracts of territory east of the Dnieper River. Polish assistance and involvement were increasingly becoming a necessary component of the balance of power in the eastern reaches of the Lithuanian domain.[51]

Under Vasili III Moscow fought a war with Lithuania and Poland between 1512 and 1522, during which in 1514 the Russians took Smolensk. That same year the Polish-Lithuanian rescue expedition fought the victorious Battle of Orsha under Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski and stopped the Duchy of Moscow's further advances. An armistice implemented in 1522 left Smolensk land and Severia in Russian hands. Another round of fighting took place during 1534–1537, when the Polish aid led by Hetman Jan Tarnowski made possible the taking of Gomel and fiercely defeated Starodub. New truce (Lithuania kept only Gomel), stabilization of the border and over two decades of peace followed.[51]

The Jagiellons and the Habsburgs; Ottoman Empire expansion

In 1515, during a congress in Vienna, a dynastic succession arrangement was agreed to between Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and the Jagiellon brothers, Vladislas II of Bohemia and Hungary and Sigismund I of Poland and Lithuania. It was supposed to end the Emperor's support for Poland's enemies, the Teutonic and Russian states, but after the election of Charles V, Maximilian's successor in 1519, the relations with Sigismund had worsened.[53]

The Jagiellon rivalry with the House of Habsburg in central Europe was ultimately resolved to the Habsburgs' advantage. The decisive factor that damaged or weakened the monarchies of the last Jagiellons was the Ottoman Empire's Turkish expansion. Hungary's vulnerability greatly increased after Suleiman the Magnificent took the Belgrade fortress in 1521. To prevent Poland from extending military aid to Hungary, Suleiman had a Tatar-Turkish force raid southeastern Poland–Lithuania in 1524. The Hungarian army was defeated in 1526 at the Battle of Mohács, where the young Louis II Jagiellon, son of Vladislas II, was killed. Subsequently, after a period of internal strife and external intervention, Hungary was partitioned between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans.[53]

The 1526 death of Janusz III of Masovia, the last of the Masovian Piast dukes line (a remnant of the fragmentation period divisions), enabled Sigismund I to finalize the incorporation of Masovia into the Polish Crown in 1529.[54]

From the early 16th century the Pokuttya border region was contested by Poland and Moldavia (see Battle of Obertyn). A peace with Moldavia took effect in 1538 and Pokuttya remained Polish. An "eternal peace" with the Ottoman Empire was negotiated by Poland in 1533 to secure frontier areas. Moldavia had fallen under Turkish domination, but Polish-Lithuanian magnates remained actively involved there. Sigismund II Augustus even claimed "jurisdiction" and in 1569 accepted a formal, short-lived suzerainty over Moldavia.[53]

Livonia; struggle for Baltic area domination

In the 16th century the Grand Duchy of Lithuania became increasingly interested in extending its territorial rule to Livonia, especially to gain control of Baltic seaports, such as Riga, and for other economic benefits. Livonia was by the 1550s largely Lutheran,[55] traditionally ruled by the Brothers of the Sword knightly order. This put Poland and Lithuania on a collision course with Moscow and other regional powers, which had also attempted expansion in that area.[56]

Soon after the Treaty of Kraków of 1525, Albrecht (Albert) of Hohenzollern planned a Polish–Lithuanian fief in Livonia, seeking a dominant position for his brother Wilhelm, the Archbishop of Riga. What happened instead was the establishment of a Livonian pro-Polish–Lithuanian party or faction. Internal fighting in Livonia took place when the Grand Master of the Brothers concluded a treaty with Moscow in 1554, declaring his state's neutrality regarding the Russian–Lithuanian conflict. Supported by Albrecht and the magnates, Sigismund II declared a war on the Order. Grand Master Wilhelm von Fürstenberg accepted the Polish–Lithuanian conditions without a fight, and according to the 1557 Treaty of Pozvol, a military alliance obliged the Livonian state to support Lithuania against Moscow.[56]

.png.webp)

Other powers aspiring to the Livonian Baltic access responded by partitioning the Livonian state, which triggered the lengthy Livonian War, fought between 1558 and 1583. Ivan IV of Russia took Dorpat (Tartu) and Narva in 1558, and soon the Danes and Swedes had occupied other parts of the country. To protect the integrity of their country, the Livonians now sought a union with the Polish–Lithuanian state. Gotthard Kettler, the new Grand Master, met in Vilnius (Vilna, Wilno) with Sigismund Augustus in 1561 and declared Livonia a vassal state under the Polish king. The Union of Vilnius called for secularization of the Brothers of the Sword Order and incorporation of the newly established Duchy of Livonia into the Rzeczpospolita ("Republic") as an autonomous entity. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was also created as a separate fief, to be ruled by Kettler. Sigismund II obliged himself to recover the parts of Livonia lost to Moscow and the Baltic powers, which had led to grueling wars with Russia (1558–1570 and 1577–1582) and heavy struggles also concerning the fundamental issues of control of the Baltic trade and freedom of navigation.[56]

The Baltic region policies of the last Jagiellon king and his advisors were the most mature of 16th-century Poland's strategic programs. The outcome of the efforts in that area was to a considerable extent successful for the Commonwealth. The wars concluded during the reign of King Stephen Báthory.[56]

Poland and Lithuania in real union under Sigismund II

Sigismund II's childlessness added urgency to the idea of turning the personal union between Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into a more permanent and tighter relationship; it was also a priority for the execution movement. Lithuania's laws were codified and reforms enacted in 1529, 1557, 1565–1566 and 1588, gradually making its social, legal and economic system similar to that of Poland, with the expanding role of the middle and lower nobility.[57] Fighting wars with Moscow under Ivan IV and the threat perceived from that direction provided additional motivation for the real union for both Poland and Lithuania.[58]

The process of negotiating the actual arrangements turned out to be difficult and lasted from 1563 to 1569, with the Lithuanian magnates, worried about losing their dominant position, being at times uncooperative. It took Sigismunt II's unilateral declaration of the incorporation into the Polish Crown of substantial disputed border regions, including most of Lithuanian Ukraine, to make the Lithuanian magnates rejoin the process, and participate in the swearing of the act of the Union of Lublin on July 1, 1569. Lithuania for the near future was becoming more secure on the eastern front. Its increasingly Polonized nobility made in the coming centuries great contributions to the Commonwealth's culture, but at the cost of Lithuanian national development.[58]

The Lithuanian language survived as a peasant vernacular and also as a written language in religious use, from the publication of the Lithuanian Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas in 1547.[59] The Ruthenian language was and remained in the Grand Duchy's official use even after the Union, until the takeover of Polish.[60]

The Commonwealth: multicultural, magnate dominated

By the Union of Lublin a unified Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was created, stretching from the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian mountains to present-day Belarus and western and central Ukraine (which earlier had been Kievan Rus' principalities). Within the new federation some degree of formal separateness of Poland and Lithuania was retained (distinct state offices, armies, treasuries and judicial systems), but the union became a multinational entity with a common monarch, parliament, monetary system and foreign-military policy, in which only the nobility enjoyed full citizenship rights. Moreover, the nobility's uppermost stratum was about to assume the dominant role in the Commonwealth, as magnate factions were acquiring the ability to manipulate and control the rest of szlachta to their clique's private advantage. This trend, facilitated further by the liberal settlement and land acquisition consequences of the union,[61] was becoming apparent at the time of, or soon after the 1572 death of Sigismund Augustus, the last monarch of the Jagiellonian dynasty.[58]

One of the most salient characteristics of the newly established Commonwealth was its multiethnicity, and accordingly diversity of religious faiths and denominations. Among the peoples represented were Poles (about 50% or less of the total population), Lithuanians, Latvians, Rus' people (corresponding to today's Belarusians, Ukrainians, Russians or their East Slavic ancestors), Germans, Estonians, Jews, Armenians, Tatars and Czechs, among others, for example smaller West European groups. As for the main social segments in the early 17th century, nearly 70% of the Commonwealth's population were peasants, over 20% residents of towns, and less than 10% nobles and clergy combined. The total population, estimated at 8–10 million, kept growing dynamically until the middle of the century.[62] The Slavic populations of the eastern lands, Rus' or Ruthenia, were solidly, except for the Polish colonizing nobility (and Polonized elements of local nobility), Eastern Orthodox, which portended future trouble for the Commonwealth.[58][63][64]

Jewish settlement

Poland had become the home to Europe's largest Jewish population, as royal edicts guaranteeing Jewish safety and religious freedom, issued during the 13th century (Bolesław the Pious, Statute of Kalisz of 1264), contrasted with bouts of persecution in Western Europe.[65] This persecution intensified following the Black Death of 1348–1349, when some in the West blamed the outbreak of the plague on the Jews. As scapegoats were sought, the increased Jewish persecution led to pogroms and mass killings in a number of German cities, which caused an exodus of survivors heading east. Much of Poland was spared from the Black Death, and Jewish immigration brought their valuable contributions and abilities to the rising state.[66] The number of Jews in Poland kept increasing throughout the Middle Ages; the population had reached about 30,000 toward the end of the 15th century,[67] and, as refugees escaping further persecution elsewhere kept streaming in, 150,000 in the 16th century.[68] A royal privilege issued in 1532 granted the Jews freedom to trade anywhere within the kingdom.[68] Massacres and expulsions from many German states continued until 1552–1553.[69] By the mid-16th century, 80% of the world's Jews lived and flourished in Poland and in Lithuania; most of western and central Europe was by that time closed to Jews.[69][70] In Poland–Lithuania the Jews were increasingly finding employment as managers and intermediaries, facilitating the functioning of and collecting revenue in huge magnate-owned land estates, especially in the eastern borderlands, developing into an indispensable mercantile and administrative class.[71] Despite the partial resettlement of Jews in Western Europe following the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), a great majority of world Jewry had lived in Eastern Europe (in the Commonwealth and in the regions further east and south, where many migrated), until the 1940s.[69]

See also

Notes

a.^ This is true especially regarding legislative matters and legal framework. Despite the restrictions the nobility imposed on the monarchs, the Polish kings had never become figureheads. In practice they wielded considerable executive power, up to and including the last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski. Some were at times even accused of absolutist tendencies, and it may be for the lack of sufficiently strong personalities or favorable circumstances that none of the kings had succeeded in significant and lasting strengthening of the monarchy.[72]

b.^ 13 in Greater Poland, 59 in Lesser Poland, 32 in Mazovia, and 153 in Red Ruthenia.[73]

References

- ↑ She had been crowned as "king of Poland" (Latin: Rex Poloniæ) in 1384.

- 1 2 3 4 Wyrozumski 1986

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986

- 1 2 3 Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 178–180

- ↑ Davies 1998, pp. 392, 461–463

- ↑ Krzysztof Baczkowski – Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506) (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), p. 55; Fogra, Kraków 1999, ISBN 83-85719-40-7

- ↑ A Traveller's History of Poland, by John Radzilowski; Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2007, ISBN 1-56656-655-X, p. 63-65

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition 2006, ISBN 0-521-61857-6, p. 68-69

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 180–190

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 41

- ↑ Stopka 1999, p. 91

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 190–195

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 195–198, 201–203

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 198–206

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 206–207

- 1 2 3 Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 207–213

- ↑ 'Stopka 1999, p. 86

- ↑ "Russian Interaction with Foreign Lands". Strangelove.net. 2007-10-06. Archived from the original on 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "List of Wars of the Crimean Tatars". Zum.de. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 213–215

- ↑ Krzysztof Baczkowski – Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506) (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), p. 302

- ↑ Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 215–221

- 1 2 3 4 Wyrozumski 1986, pp. 221–225

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 73

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 24–38

- 1 2 Józef Andrzej Gierowski – Historia Polski 1505–1764 (History of Poland 1505–1764), p. 24-38

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 65, 68

- 1 2 3 Gierowski 1986, pp. 38–53

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gierowski 1986, pp. 53–64

- 1 2 Wacław Urban, Epizod reformacyjny (The Reformation episode), p.30. Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Kraków 1988, ISBN 83-03-02501-5.

- ↑ Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, Monarchia Jagiellonów, 1399–1586 (The Jagiellonian Monarchy: 1399–1586), p. 131-132, Urszula Augustyniak. Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2003, ISBN 83-7384-018-4.

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 104

- 1 2 Davies 2005, pp. 118

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 67–71

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986, pp. 71–74

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gierowski 1986, pp. 74–79

- ↑ Stanisław Grzybowski – Dzieje Polski i Litwy (1506-1648) (History of Poland and Lithuania (1506-1648)), p. 206, Fogra, Kraków 2000, ISBN 83-85719-48-2

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986, pp. 79–84

- ↑ Anita J. Prażmowska – A History of Poland, 2004 Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-97253-8, p. 84

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 84–85

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986, pp. 85–88

- ↑ Waclaw Uruszczak, "The Implementation of Domestic Policy in Poland under the Last Two Jagellonian Kings, 1506-1572." Parliaments, Estates & Representation (1987) 7#2 pp 133-144. ISSN 0260-6755, not online

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 61

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gierowski 1986, pp. 92–105

- ↑ Basista 1999, p. 104

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 116–118

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 48, 50

- 1 2 Gierowski 1986, pp. 119–121

- ↑ Basista 1999, p. 109

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 104–105

- 1 2 Gierowski 1986, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Andrzej Romanowski, Zaszczuć osobnika Jasienicę (Harass the Jasienica individual). Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper wyborcza.pl, 2010-03-12

- 1 2 3 Gierowski 1986, pp. 122–125, 151

- ↑ Basista 1999, pp. 109–110

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 58

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986, pp. 125–130

- ↑ Basista 1999, pp. 115, 117

- 1 2 3 4 Gierowski 1986, pp. 105–109

- ↑ Davies 1998, p. 228

- ↑ Davies 1998, pp. 392

- ↑ A Concise History of Poland, by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, p. 81

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich, Adam Żurek, Monarchia Jagiellonów (1399–1586) (Jagiellonian monarchy (1399–1586)), p. 160-161, Krzysztof Mikulski. Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2003, ISBN 83-7384-018-4.

- ↑ Ilustrowane dzieje Polski (Illustrated History of Poland) by Dariusz Banaszak, Tomasz Biber, Maciej Leszczyński, p. 40. 1996 Podsiedlik-Raniowski i Spółka, ISBN 83-7212-020-X.

- ↑ A Traveller's History of Poland, by John Radzilowski, p. 44–45

- ↑ Davies 1998, pp. 409–412

- ↑ Krzysztof Baczkowski – Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506) (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), p. 274–276

- 1 2 Gierowski 1986, p. 46

- 1 2 3 Richard Overy (2010), The Times Complete History of the World, Eights Edition, p. 116–117. London: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-00-788089-8.

- ↑ "European Jewish Congress – Poland". Eurojewcong.org. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ A Traveller's History of Poland, by John Radzilowski, p. 100, 113

- ↑ Gierowski 1986, pp. 144–146, 258–261

- ↑ A. Janeczek. "Town and country in the Polish Commonwealth, 1350-1650." In: S. R. Epstein. Town and Country in Europe, 1300-1800. Cambridge University Press. 2004. p. 164.

- Gierowski, Józef Andrzej (1986). Historia Polski 1505–1764 (History of Poland 1505–1764). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (Polish Scientific Publishers PWN). ISBN 83-01-03732-6.

- Wyrozumski, Jerzy (1986). Historia Polski do roku 1505 (History of Poland until 1505). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (Polish Scientific Publishers PWN). ISBN 83-01-03732-6.

- Stopka, Krzysztof (1999). Andrzej Chwalba (ed.). Kalendarium dziejów Polski (Chronology of Polish History),. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 83-08-02855-1.

- Basista, Jakub (1999). Andrzej Chwalba (ed.). Kalendarium dziejów Polski (Chronology of Polish History),. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 83-08-02855-1.

- Davies, Norman (1998). Europe: A History. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-097468-0.

- Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9.

Further reading

- The Cambridge History of Poland (two vols., 1941–1950) online edition vol 1 to 1696

- Butterwick, Richard, ed. The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, c. 1500-1795. Palgrave, 2001. 249 pp. online edition

- Davies, Norman. Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland. Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground: A History of Poland. 2 vol. Columbia U. Press, 1982.

- Pogonowski, Iwo Cyprian. Poland: A Historical Atlas. Hippocrene, 1987. 321 pp.

- Sanford, George. Historical Dictionary of Poland. Scarecrow Press, 2003. 291 pp.

- Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. U. of Washington Press, 2001.

- Zamoyski, Adam. The Polish Way. Hippocrene Books, 1987. 397 pp.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)