| Japanese coup d'état in French Indochina | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II | |||||||||

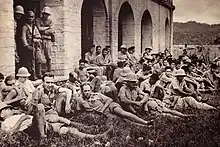

French colonial troops retreating to the Chinese border during the Japanese Coup of March 1945 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Air support: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 55,000[3] |

65,000[Note A] 25 light tanks 100 aircraft[4] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| ~ 1,000 killed or wounded |

4,200 killed[Note B] 15,000 captured or interned[Note C] | ||||||||

The Japanese coup d'état in French Indochina, known as Meigō Sakusen (明号作戦, Operation Bright Moon),[5][6] was a Japanese operation that took place on 9 March 1945, towards the end of World War II. With Japanese forces losing the war and the threat of an Allied invasion of Indochina imminent, the Japanese were concerned about an uprising against them by French colonial forces.[7]

Despite the French having anticipated an attack, the Japanese struck in a military campaign attacking garrisons all over the colony. The French were caught off guard and all of the garrisons were overrun, with some then having to escape to Nationalist China, where they were harshly interned.[2] The Japanese replaced French officials, and effectively dismantled their control of Indochina. The Japanese were then able to install and create a new Empire of Vietnam, Kingdom of Kampuchea and Kingdom of Luang Phrabang which under their direction would acquiesce with their military presence and forestall a potential invasion by the Allies.[8][9]

Background

.jpg.webp)

French Indochina comprised the colony of Cochinchina and the protectorates of Annam, Cambodia and Tonkin, and the mixed region of Laos. After the fall of France in June 1940 the French Indochinese government had remained loyal to the Vichy regime, which collaborated with the Axis powers. The following month governor Admiral Jean Decoux signed an agreement under which Japanese forces were permitted to occupy bases across Indochina. In September the same year Japanese troops invaded and took control of Northern Indochina, and then in July 1941 they occupied the Southern half as well. The Japanese allowed Vichy French troops and the administration to continue on albeit as puppets.[10]

By 1944 with the war going against the Japanese after defeats in Burma and the Philippines they then feared an Allied offensive in French Indochina. The Japanese were already suspicious of the French; the liberation of Paris in August 1944 raised further doubts as to where the loyalties of the colonial administration lay.[10] The Vichy regime by this time had ceased to exist, but its colonial administration was still in place in Indochina, though Decoux had recognized and contacted the Provisional Government of the French Republic led by Charles de Gaulle.[11] Decoux got a cold response from de Gaulle and was stripped of his powers as governor general but was ordered to maintain his post with orders to deceive the Japanese.[12] Instead Decoux's army commander General Eugène Mordant secretly became the Provisional Government's delegate and the head of all resistance and underground activities in Indochina. Mordant however was careless – he was too talkative and had an inability to keep his preparations secret, so much so that the Japanese Kempeitai swiftly uncovered the plot against them and discussed the next move against the French.

Prelude

British intelligence—mission Force 136—air-dropped several Free French operatives into Indochina in late 1944. They provided detailed information on targets, mostly related to ship movements, along the coast to British headquarters in India and China, who in turn transmitted them to the Americans.[13] During the South China Sea raid in January 1945 American carriers' aircraft sank twenty-four vessels and damaged another thirteen. Six U.S. navy pilots were shot down but were picked up by French military authorities and housed in the central prison of Saigon for safe keeping.[7] The French refused to give the Americans up and when the Japanese prepared to storm the prison the men were smuggled out. The Japanese demanded their surrender but Decoux refused and General Yuitsu Tsuchihashi, the Japanese commander, decided to act.[7] Tsuchihashi could no longer trust Decoux to control his subordinates and asked for orders from Tokyo. The Japanese High Command were reluctant for another front to be opened up in an already poor situation. Nevertheless, they ordered Tsuchihashi to offer Decoux an ultimatum and if this was rejected then at his discretion a coup would be authorised.[14] With this coup the Japanese planned to overthrow the colonial administration and intern or destroy the French army in Indochina. Several friendly puppet governments would then be established and win the support of the indigenous populations.[15]

Opposing forces

In early 1945 the French Indochina army still outnumbered the Japanese in the colony and comprised about 65,000 men, of whom 48,500 were locally recruited Tirailleurs indochinois under French officers.[16][17] The remainder were French regulars of the Colonial Army plus three battalions of the Foreign Legion. A separate force of indigenous gardes indochinois (gendarmerie) numbered 27,000.[16] Since the fall of France in June 1940 no replacements or supplies had been received from outside Indochina. By March 1945 only about 30,000 French troops could be described as fully combat ready,[17] the remainder serving in garrison or support units. At the beginning of 1945 the understrength Japanese Thirty-Eighth Army was composed of 30,000 troops, a force that was substantially increased by 25,000 reinforcements brought in from China, Thailand, and Burma in the following months.[18]

The coup

In early March 1945 Japanese forces were redeployed around the main French garrison towns throughout Indochina, linked by radio to the Southern area headquarters.[7] French officers and civilian officials were however forewarned of an attack through troop movements, and some garrisons were put on alert. The Japanese envoy in Saigon Ambassador Shunichi Matsumoto declared to Decoux that since an Allied landing in Indochina was inevitable, Tokyo command wished to put into place a "common defence" of Indochina. Decoux however resisted stating that this would be a catalyst for an Allied invasion but suggested that Japanese control would be accepted if they actually invaded. This was not enough and Tsuchihashi accused Decoux of playing for time.[14]

On 9 March, after more stalling by Decoux, Tsuchihashi delivered an ultimatum for French troops to disarm. Decoux sent a messenger to Matsumoto urging further negotiations but the message arrived at the wrong building. Tsuchihashi, assuming that Decoux had rejected the ultimatum, immediately ordered commencement of the coup.[19]

That evening Japanese forces moved against the French in every center.[2] In some instances French troops and the Garde Indochinoise were able to resist attempts to disarm them, with the result that fighting took place in Saigon, Hanoi, Haiphong and Nha Trang and the Northern frontier.[2] Japan issued instructions to the government of Thailand to seal off its border with Indochina and to arrest all French and Indochinese residents within its territory. Instead, Thailand began negotiating with the Japanese over their course of action, and by the end of March they hadn't fully complied with the demands.[20] Dōmei Radio (the official Japanese propaganda channel) announced that pro-Japanese independence organizations in Tonkin formed a federation to promote a free Indochina and cooperation with the Japanese.[21]

The 11th R.I.C (régiment d'infanterie coloniale) based at the Martin de Pallieres barracks in Saigon were surrounded and disarmed after their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Moreau, was arrested. In Hue there was sporadic fighting; the Garde Indochinoise, who provided security for the résident supérieur, fought for 19 hours against the Japanese before their barracks was overrun and destroyed.[19] Three hundred men, one third of them French, managed to elude the Japanese and escape to the A Sầu Valley. However, over the next three days, they succumbed to hunger, disease and betrayals - many surrendered while others fought their way into Laos where only a handful survived. Meanwhile, Mordant led opposition by the garrison of Hanoi for several hours but was forced to capitulate, with 292 dead on the French side and 212 Japanese.[2]

An attempt to disarm a Vietnamese garrison ended badly for the Japanese when 600 of them marched into Quảng Ngãi.[2] The Vietnamese nationalists had been armed with automatic weapons supplied by the OSS parachuted nearby at Kontum. The Japanese had been led to believe that these men would readily defect but the Vietnamese ambushed the Japanese. Losing only three killed and seventeen wounded they inflicted 143 killed and another 205 wounded on the Japanese before they too were overcome.[2] A much bigger force of Japanese came the next day but they found the garrison empty. In Annam and Cochinchina only token resistance was offered and most garrisons, small as they were, surrendered.

Further north the French had the sympathy of many indigenous peoples. Several hundred Laotians volunteered to be armed as guerrillas against the Japanese; French officers organized them into detachments but turned away those they did not have weapons for.[22]

In Haiphong the Japanese assaulted the Bouet barracks: headquarters of Colonel Henry Lapierre's 1st Tonkin Brigade. Using heavy mortar and machine gun fire, one position was taken after another before the barracks fell and Lapierre ordered a ceasefire. Lapierre refused to sign surrender messages for the remaining garrisons in the area. Codebooks had also been burnt which meant the Japanese then had to deal with the other garrisons by force.[23]

In Laos, Vientiane, Thakhek and Luang Prabang were taken by the Japanese without much resistance.[24] In Cambodia the Japanese with 8,000 men seized Phnom Penh and all major towns in the same manner. All French personnel in the cities on both regions were either interned or in some cases executed.[25]

The Japanese strikes at the French in the Northern Frontier in general saw the heaviest fighting.[23] One of the first places they needed to take and where they amassed the 22nd division was at Lang Son, a strategic fort near the Chinese border.[2]

Battle of Lạng Sơn

The defences of Lạng Sơn consisted of a series of fort complexes built by the French to defend against a Chinese invasion.[23] The main fortress was the Fort Brière de l'Isle. Inside was a French garrison of nearly 4,000 men, many of them Tonkinese, with units of the French Foreign Legion. Once the Japanese had cut off all communications to the forts they invited General Émile Lemonnier, the commander of the border region, to a banquet at the headquarters of the 22nd division of the Imperial Japanese Army.[2] Lemonnier declined to attend the event, but allowed some of his staff to go in his place.[9] They were taken prisoner and soon after the Japanese bombarded Fort Brière de l'Isle, attacking with infantry and tanks.[23] The small forts outside had to defend themselves in isolation; they did so for a time, proving impenetrable, and the Japanese were repelled with some loss. They tried again the next day and succeeded in taking the outer positions. Finally, the main fortress of Brière de l'Isle was overrun after heavy fighting.[9]

Lemonnier was subsequently taken prisoner himself and ordered by a Japanese general to sign a document formally surrendering the forces under his command.[9] Lemonnier refused to sign the documents. As a result, the Japanese took him outside where they forced him to dig a grave along with French Resident-superior (Résident-général) Camille Auphelle.[23] Lemonnier again was ordered to sign the surrender documents and again refused. The Japanese subsequently beheaded him.[9] The Japanese then machine-gunned some of the prisoners and either beheaded or bayoneted the wounded survivors.[26]

The battle of Lạng Sơn cost the French heavy casualties and their force on the border was effectively destroyed. European losses were 544 killed, of which 387 had been executed after capture. In addition 1,832 Tonkinese colonial troops were killed (including 103 who were executed) while another 1,000 were taken prisoner.[2] On 12 March planes of the US Fourteenth Air Force flying in support of the French, mistook a column of Tonkinese prisoners for Japanese and bombed and strafed them. Reportedly between 400 and 600[27] of the prisoners were killed or wounded.[2]

On the 12th the Japanese then advanced further north to the border town of Dong Dang where a company of the 3rd Regiment of Tonkinese Rifles and a battery of colonial artillery were based.[28] Following Lemonnier's refusal to order a general surrender, the Japanese launched an attack against the town. The French resisted for three days. The Japanese were then reinforced by two regiments from 22nd Division from Lạng Sơn and finally overran the French colonial force. Fifty-three survivors were beheaded or bayoneted to death.[23]

Retreat to China

In the North West General Gabriel Sabattier's Tonkin division had enough time to be spared an assault by the Japanese and were able to retreat northwest from their base in Hanoi, hoping to reach the Chinese border.[23] However they were soon harried by the Japanese air force and artillery fire, being forced to abandon all their heavy equipment as they crossed the Red River.[2] Sabattier then found that the Japanese had blocked the most important border crossings at Lao Cai and Ha Giang during the reductions of Lang Son and Dang Dong. Contact was then lost with Major-General Marcel Alessandri' s 2nd Tonkin Brigade, numbering some 5,700 French and colonial troops. This column included three Foreign Legion battalions of the 5eme Etranger. Their only option was to fight their own way to China.[28]

The United States and China were reluctant to start a large-scale operation to restore French authority, as they did not favour colonial rule, and had little sympathy for the Vichy regime which had formerly collaborated with the Japanese. Both countries ordered that their forces provide no assistance to the French, but American general Claire Lee Chennault went against orders, and aircraft from his 51st Fighter Group and 27th Troop Carrier Squadron flew support missions as well as dropping medical supplies for Sabattier's forces retreating into China.[1] Between 12 and 28 March, the Americans flew thirty-four bombing, strafing and reconnaissance missions over the North of Indochina but they had little effect in stemming the Japanese advance.[29]

By mid April Alessandri, having realised he was on his own, split his force into two. Soon a combination of disease, ration shortages and low morale forced him into a difficult decision. With reluctance he disarmed and disbanded his locally recruited colonial troops, leaving them to their fate in a measure which angered French and Vietnamese alike. Many of the tirailleurs were far from their homes and some were captured by the Japanese. Others joined the Viet Minh. The remaining French and Foreign Legion units gradually discarded all of their heavy weapons, motor vehicles and left behind several tons of ammunition without destroying any of it.[23] The division were soon reduced in numbers by disease and missing men as they moved towards Son La and Dien Bien Phu where they fought costly rearguard actions.[8][28]

By this time de Gaulle had been informed of the situation in Indochina and then swiftly told Sabattier via radio orders to maintain a presence in Indochina for the sake of France's pride at all costs.[2] By 6 May however many of the remaining members of the Tonkin Division were over the Chinese border where they were interned under harsh conditions.[8] Between 9 March and 2 May the Tonkin division had suffered heavily; many had died or were invalided by disease. In combat 774 had been killed and 283 wounded with another 303 missing or captured.[2]

Independence

During the coup the Japanese urged the declarations of independence from the traditional rulers of the different regions, resulting in the creation of the Empire of Vietnam, the independence of the Kingdom of Kampuchea, and the Kingdom of Luang Phrabang under the Japanese direction.

On 11 March 1945, Emperor Bảo Đại was permitted to announce the Vietnamese "independence"; this declaration had been prepared by Yokoyama Seiko, Minister for Economic Affairs of the Japanese diplomatic mission in Indochina and later advisor to Bao Dai[30] Bảo Đại complied in Vietnam where they set up a puppet government headed by Tran Trong Kim[31] and which collaborated with the Japanese. King Norodom Sihanouk also obeyed, but the Japanese did not trust the Francophile monarch.[32]

Nationalist leader Son Ngoc Thanh, who had been exiled in Japan and was considered a more trustworthy ally than Sihanouk, returned to Cambodia and became Minister of foreign affairs in May and then Prime Minister in August.[32] In Laos however, King Sisavang Vong of Luang Phrabang, who favoured French rule, refused to declare independence, finding himself at odds with his Prime Minister, Prince Phetsarath Ratanavongsa, but eventually acceded on 8 April.[33]

On 15 May with the coup complete and the nominally independent states set up, General Tsuchihashi declared mopping up operations complete and released several brigades to other fronts.[29]

Aftermath

The coup had, in the words of diplomat Jean Sainteny, "wrecked a colonial enterprise that had been in existence for 80 years."[5]

French losses were heavy. 15,000 French soldiers in total were held prisoner by the Japanese. Nearly 4,200 were killed with many executed after surrendering - about half of these were European or French metropolitan troops.[14] Practically all French civil and military leaders as well as plantation owners were made prisoners, including Decoux. They were confined either in specific districts of big cities or in camps. Those who were suspected of armed resistance were jailed in the Kempeitai prison in bamboo cages and were tortured and cruelly interrogated.[34] The locally recruited tirailleurs and gardes indochinois who had made up the majority of the French military and police forces, effectively ceased to exist. About a thousand were killed in the fighting or executed after surrender. Some joined pro-Japanese militias or Vietnamese nationalist guerrillas. Deprived of their French cadres, many dispersed to their villages of origin. Over three thousand reached Chinese territory as part of the retreating French columns.[35]

What was left of the French forces that had escaped the Japanese attempted to join the resistance groups where they had more latitude for action in Laos. The Japanese there had less control over this part of the territory and with Lao guerilla groups managed to gain control of several rural areas.[36] Elsewhere the resistance failed to materialize as the Vietnamese refused to help the French.[37] They also lacked precise orders and communications from the provisional government as well as the practical means to mount any large-scale operations.[38]

In northern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh started their own guerilla campaign with the help of the American OSS who trained and supplied them with arms and funds. The famine in Vietnam had caused resentment among the population both towards the French and the Japanese (although US bombing played a part).[39] They established their bases in the countryside without meeting much resistance from the Japanese who were mostly present in the cities.[40] Viet Minh numbers increased especially after they ransacked between 75 and 100 warehouses, dispersed the rice and refused to pay taxes.[39] In July OSS with the Viet Minh—some of whom were remnants of Sabattiers division—went over the border to conduct operations.[41] Their actions were limited to a few attacks against Japanese military posts.[42] Most of these were unsuccessful however as the Viet Minh lacked the military force to launch any kind of attack against the Japanese.[37]

Viet Minh takeover

Japan surrendered when Emperor Hirohito announced the capitulation on 16 August. Soon after Japanese garrisons officially handed control to Bảo Đại in the North and the United Party in the South. This, however, allowed nationalist groups to take over public buildings in most of the major cities. The Viet Minh were thus presented with a power vacuum, and on the 19th the August Revolution commenced.[8] On 25 August, Bảo Đại was forced to abdicate in favour of Ho and the Viet Minh - they took control of Hanoi and most of French Indochina. The Japanese did not oppose the Viet Minh's takeover as they were reluctant to let the French retake control of their colony.[43] Ho Chi Minh proclaimed Vietnam's independence on 2 September 1945.

Allied takeover

Charles de Gaulle in Paris criticized the United States, United Kingdom and China for not helping the French in Indochina during the coup.[44] De Gaulle however affirmed that France would regain control of Indochina.[45]

French Indochina had been left in chaos by the Japanese occupation. On 11 September British and Indian troops of the 20th Indian Division under Major General Douglas Gracey arrived at Saigon as part of Operation Masterdom. After the Japanese surrender all French prisoners had been gathered on the outskirts of Saigon and Hanoi and the sentries disappeared altogether on 18 September. The six months spent in captivity cost an additional 1,500 lives. By 22 September 1945, all prisoners were liberated by Gracey's men and were then armed and dispatched in combat units towards Saigon to conquer it from the Vietminh.[46] They were later joined by the French Far East Expeditionary Corps (which had been established to fight the Japanese), having arrived a few weeks later.[47]

Around the same time General Lu Han's 200,000 Chinese National Revolutionary troops occupied Indochina north of the 16th parallel.[48] 90,000 arrived by October, the 62nd army came on 26 September to Nam Dinh and Haiphong. Lang Son and Cao Bang were occupied by the Guangxi 62nd army corps and the Red River region and Lai Cai were occupied by a column from Yunnan. Lu Han occupied the French governor general's palace after ejecting the French staff under Sainteny.[49] Ho Chi Minh sent a cable on 17 October 1945 to American President Harry S. Truman calling on him, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, Premier Stalin and Premier Attlee to go to the United Nations against France and demand France not be allowed to return to occupy Vietnam, accusing France of having sold out and cheated the Allies by surrendering Indochina to Japan and that France had no right to return.[50]

On 9 March 1946, the French Permanent Military Tribunal in Saigon (FPMTS) also known as the Saigon Trials was set up to investigate conventional war crimes ("Class B") and crimes against humanity ("Class C") committed by the Japanese forces after the 9 March 1945 coup d'état.[51][52] The FPMTS examined war crimes committed between 9 March 1945 and 15 August 1945.[53] The FPMTS tried a total of 230 Japanese defendants in 39 separate trials, taking place between October 1946 and March 1950.[54] According to Chizuru Namba, 112 of the defendants received prison sentences, 63 were executed, 23 received life imprisonment and 31 were acquitted. Further 228 people were condemned in absentia.[54][55]

Japanese soldiers in French Indochina after 1945

After 1945 a number of Japanese soldiers would stay behind in French Indochina, several of them took Vietnamese war brides and would sire children with them (Hāfu).[56]

Legacy

On 25 March 1957, the former Rue des Tuileries (1st district of Paris) was renamed Avenue Général-Lemonnier in honour of the French general who refused to capitulate at the Battle of Lang Son. A plaque is located there describing the general's heroic refusal to surrender.[57]

See also

References

- Notes

- Citations

- 1 2 Fall pp 24-25

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dommen p 80-82

- ↑ Porch pp 512-13

- ↑ Ehrengardt, Christian J; Shores, Christopher (1985). L'Aviation de Vichy au combat: Tome 1: Les campagnes oubliées, 3 juillet 1940 - 27 novembre 1942. Charles-Lavauzelle.

- 1 2 Hock, David Koh Wee (2007). Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 23–35. ISBN 9789812304681.

- ↑ Kiyoko Kurusu Nitz (1983), "Japanese Military Policy Towards French Indochina during the Second World War: The Road to the Meigo Sakusen (9 March 1945)", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 14(2): 328–53.

- 1 2 3 4 Dommen p 78

- 1 2 3 4 Windrow pp 81-82

- 1 2 3 4 5 McLeave pp 199–204

- 1 2 Hammer, p. 94

- ↑ Jacques Dalloz, La Guerre d'Indochine, Seuil, 1987, pp 56–59

- ↑ Marr, pp 47-48

- ↑ Marr p 43

- 1 2 3 4 Dreifort pp 240

- ↑ Smith, T. O. (2014). Vietnam and the Unravelling of Empire: General Gracey in Asia 1942–1951 (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 9781137448712.

- 1 2 Rives, Maurice (1999). Les Linh Tap. p. 93. ISBN 2-7025-0436-1.

- 1 2 Marr 1995, p. 51.

- ↑ Porch pp 512-13

- 1 2 Marr pp 55-57

- ↑ OSS 1945, p. 2.

- ↑ OSS 1945, p. 3.

- ↑ Hammer, p. 40

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Marr pp. 59-60

- ↑ Askew, Long & Logan pp 108-11

- ↑ Osbourne p. 117

- ↑ Porch p 564

- ↑ Rives, Maurice (1999). Les Linh Tap. p. 95. ISBN 2-7025-0436-1.

- 1 2 3 Patti p 75

- 1 2 3 Marr p. 61

- ↑ P.42

- ↑ Logevall, pp. 67-72

- 1 2 Kiernan, p.51

- ↑ Ivarsson pp 208-10

- ↑ Buttinger, Joseph (1967). Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled. Pall Mall P. p. 600.

- ↑ Rives, Maurice (1999). Les Linh Tap. p. 97. ISBN 2-7025-0436-1.

- ↑ Dommen pp. 91-92

- 1 2 Advice and Support: The Early Years, 1941-1960. Government Printing Office. 1983. p. 41. ISBN 9780160899553.

- ↑ Grandjean (2004)

- 1 2 Gunn, Geoffrey (2011) ‘ The Great Vietnamese Famine of 1944-45 Revisited', The Asia-Pacific Journal, 9(5), no 4 (31 January 2011). http://www.japanfocus.org/-Geoffrey-Gunn/3483

- ↑ Laurent Cesari, L'Indochine en guerres, 1945-1993, Belin, 1995, pp 30-31

- ↑ Generous p. 19

- ↑ Philippe Devillers, Histoire du Viêt Nam de 1940 à 1952, Seuil, 1952, page 133

- ↑ Cecil B. Currey, Vo Nguyên Giap – Viêt-nam, 1940–1975 : La Victoire à tout prix, Phébus, 2003, pp. 160–161

- ↑ Logevall, Fredrik (2012), Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam, New York: Random House, p.72

- ↑ Logevall p 73

- ↑ Le p. 273

- ↑ Martin Thomas (1997). "Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 28, 1997".

- ↑ Miller, Edward (2016). The Vietnam War: A Documentary Reader. Uncovering the Past: Documentary Readers in American History (illustrated ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 40. ISBN 978-1405196789.

- ↑ Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2014). Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 224. ISBN 978-1442223035.

- ↑ Ho, Chi Minh (1995). "9. Vietnam's Second Appeal to the United States: Cable to President Harry S Truman (October 17, 1945)*". In Gettleman, Marvin E.; Franklin, Jane; Young, Marilyn Blatt; Franklin, Howard Bruce (eds.). Vietnam and America: A Documented History (illustrated, revised ed.). Grove Press. p. 47. ISBN 0802133622.

- ↑ Gunn 2015.

- ↑ Schoepfel 2014, p. 120.

- ↑ Schoepfel 2016, p. 185.

- 1 2 Schoepfel 2014, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Schoepfel 2016, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Ian Harvey (6 March 2017). "Japan's Emperor and Empress Meet With Children Abandoned by Japanese Soldiers After WWII". War History Online (The place for military history news and views). Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ↑ Jacques Hillairet, Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1972, 1985, 1991, 1997 , etc. (1st ed. 1960), 1,476 p., 2 vol. (ISBN 2-7073-1054-9, OCLC 466966117), pp. 573–578

- ↑ Marr p 51

Bibliography

- Books

- Askew, Marc; Long, Colin; Logan, William (2006). Vientiane: Transformations of a Lao Landscape Routledge Studies in Asia's Transformations. Routledge. ISBN 9781134323654.

- Beryl, Williams; Smith, R. B (2012). Communist Indochina Volume 53 of Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9780415542630.

- Dommen, Arthur J (2002). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253109255.

- Dreifort, John E (1991). Myopic Grandeur: The Ambivalence of French Foreign Policy Toward the Far East, 1919–1945. Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384414.

- Fall, Bernard B (1976). Street Without Joy. Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805203301.

- Generous, Kevin M (1985). Vietnam: the secret war. Bison Books. ISBN 9780861242436.

- Grandjean, Philippe (2004). L'Indochine face au Japon: Decoux–de Gaulle, un malentendu fatal. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Gunn, Geoffrey (2014). Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Gunn, Geoffrey (2015). "The French Permanent Military Tribunal in Saigon (1945–50)". End of Empire. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Hammer, Ellen J (1955). The Struggle for Indochina 1940–1955: Vietnam and the French Experience. Stanford University Press.

- Jennings, Eric T. (2001). Vichy in the Tropics: Petain's National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940–44. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804750475.

- Le, Manh Hung (2004). The Impact of World War II on the Economy of Vietnam, 1939–45. Eastern Universities Press by Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9789812103482.

- Marr, David G. (1995). Vietnam 1945: The Quest for Power. University of California Press.

- McLeave, Hugh (1992). The Damned Die Hard. Bantam Books. ISBN 9780553299601.

- Osborne, Milton E (2008). Phnom Penh: A Cultural and Literary History Cities of the imagination. Signal Books. ISBN 9781904955405.

- Patti, Archimedes L. A (1982). Why Viet Nam?: Prelude to America's Albatross Political science, history. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520047839.

- Porch, Douglas (2013). The French Foreign Legion: A Complete History of the Legendary Fighting Force. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9781628732399.

- Schoepfel, Ann-Sophie (2014). "The War Court as a Form of State Building: The French Prosecution of Japanese War Crimes at the Saigon and Tokyo Trials". In Cheah, Wui Ling; Yi, Ping (eds.). Historical Origins of International Criminal Law: Volume 2. Torkel Opsahl Academic. pp. 119–141. ISBN 9788293081135.

- Schoepfel, Ann-Sophie (2016). "Justice and Decolonization: War Crimes on Trial in Saigon, 1946–1950". In von Lingen, Kerstin (ed.). War Crimes Trials in the Wake of Decolonization and Cold War in Asia, 1945–1956. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 167–194. ISBN 9783319429878.

- Smith, Ralph B. (1978). "The Japanese Period in Indochina and the Coup of 9 March 1945". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 9 (2): 268–301. doi:10.1017/s0022463400009784. S2CID 162631136.

- Windrow, Martin (2009). The Last Valley: Dien Bien Phu and the French Defeat in Vietnam. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780786737499.

- Journals

- Smith, Ralph B. (1978). "The Japanese Period in Indochina and the Coup of 9 March 1945". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 9 (2): 268–301. doi:10.1017/s0022463400009784. S2CID 162631136.

- Documents

- Japanese seizure of French Indochina (PDF), Current Intelligence Studies, vol. 4, Office of Strategic Services Research and Analysis Branch, 30 March 1945, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2017

External links

- The 9 March 1945 onslaught (3-part dossier)

- (in French) Japanese intervention of 1945, Dr. Jean-Philippe Liardet

- The General Sabattier in Lambaesis, French Algeria, French newsreels archives (Les Actualités Françaises), 15 July 1945