Jean Metzinger | |

|---|---|

Metzinger, before 1913 | |

| Born | Jean Dominique Antony Metzinger 24 June 1883 Nantes, France |

| Died | 3 November 1956 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Education | École des Beaux-Arts (Nantes) |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, writing, poetry |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Neo-Impressionism, Divisionism, Fauvism, Cubism |

| Website | jeanmetzinger |

Jean Dominique Antony Metzinger (French: [mɛtsɛ̃ʒe]; 24 June 1883 – 3 November 1956) was a major 20th-century French painter, theorist, writer, critic and poet, who along with Albert Gleizes wrote the first theoretical work on Cubism.[1][2][3][4] His earliest works, from 1900 to 1904, were influenced by the neo-Impressionism of Georges Seurat and Henri-Edmond Cross. Between 1904 and 1907, Metzinger worked in the Divisionist and Fauvist styles with a strong Cézannian component, leading to some of the first proto-Cubist works.

From 1908, Metzinger experimented with the faceting of form, a style that would soon become known as Cubism. His early involvement in Cubism saw him both as an influential artist and an important theorist of the movement. The idea of moving around an object in order to see it from different view-points is treated, for the first time, in Metzinger's Note sur la Peinture, published in 1910.[5] Before the emergence of Cubism, painters worked from the limiting factor of a single view-point. Metzinger, for the first time, in Note sur la peinture, enunciated the interest in representing objects as remembered from successive and subjective experiences within the context of both space and time. Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes wrote the first major treatise on Cubism in 1912, entitled Du "Cubisme". Metzinger was a founding member of the Section d'Or group of artists.

Metzinger was at the center of Cubism both because of his participation and identification of the movement when it first emerged, because of his role as intermediary among the Bateau-Lavoir group and the Section d'Or Cubists, and above all because of his artistic personality.[6] During the First World War, Metzinger furthered his role as a leading Cubist with his co-founding of the second phase of the movement, referred to as Crystal Cubism. He recognized the importance of mathematics in art, through a radical geometrization of form as an underlying architectural basis for his wartime compositions. The establishing of the basis of this new perspective, and the principles upon which an essentially non-representational art could be built, led to La Peinture et ses lois (Painting and its Laws), written by Albert Gleizes in 1922–23. As post-war reconstruction began, a series of exhibitions at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne were to highlight order and allegiance to the aesthetically pure. The collective phenomenon of Cubism—now in its advanced revisionist form—became part of a widely discussed development in French culture, with Metzinger at its helm. Crystal Cubism was the culmination of a continuous narrowing of scope in the name of a return to order; based upon the observation of the artist's relation to nature, rather than on the nature of reality itself. In terms of the separation of culture and life, this period emerges as the most important in the history of Modernism.[7]

For Metzinger, the classical vision had been an incomplete representation of real things, based on an incomplete set of laws, postulates and theorems. He believed the world was dynamic and changing in time, appearing different depending on the observer's point of view. Each of these viewpoints were equally valid according to underlying symmetries inherent in nature. For inspiration, Niels Bohr, the Danish physicist and one of the founders of quantum mechanics, hung in his office a large painting by Metzinger, La Femme au Cheval,[8] a conspicuous early example of "mobile perspective" implementation (also called simultaneity).[9]

Early life

Jean Metzinger came from a prominent military family. His great-grandfather, Nicolas Metzinger (18 May 1769 – 1838),[10] Captain in the 1st Horse Artillery Regiment, and Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, had served under Napoleon Bonaparte.[11] A street in the Sixième arrondissement of Nantes (Rue Metzinger) was named after Jean's grandfather, Charles Henri Metzinger (10 May 1814 – ?).[12] Following the early death of his father, Eugène François Metzinger, Jean pursued interests in mathematics, music and painting, though his mother, a music professor by the name of Eugénie Louise Argoud, had ambitions of his becoming a medical doctor.[13] Jean's younger brother Maurice (born 24 Oct. 1885) became a musician, excelling as a cellist.[13] By 1900 Metzinger was studying painting under Hippolyte Touront, a well-known portrait painter who taught an academic, conventional style of painting.[13] Metzinger, however, was interested in the current trends in painting.[14]

Metzinger sent three paintings to the Salon des Indépendants in 1903, and subsequently moved to Paris with the proceeds from their sale. From the age of 20, Metzinger supported himself as a professional painter. He exhibited regularly in Paris from 1903, participating in the first Salon d'Automne[15] the same year and taking part in a group show with Raoul Dufy, Lejeune and Torent, from 19 January-22 February 1903 at the gallery run by Berthe Weill, with another show November 1903.

Metzinger exhibited at Weill's gallery 23 November-21 December 1905 and again 14 January-10 February 1907, with Robert Delaunay, in 1908 (6–31 January) with André Derain, Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso, and 28 April-28 May 1910 with Derain, Georges Rouault and Kees van Dongen. He exhibited again at Weill's gallery, 17 January-1 February 1913, March 1913, June 1914 and February 1921.[16] It is at Berthe Weill's that he met Max Jacob for the first time.[13] Berthe Weill was the first Parisian art dealer to sell works of Picasso (1906). Along with Picasso and Metzinger, she promoted Matisse, Derain, Amedeo Modigliani and Maurice Utrillo.[17]

In 1904 Metzinger exhibited six paintings in the Divisionist style at the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne[18] (where he showed regularly throughout the crucial years of Cubism).[19]

In 1905 Metzinger exhibited eight paintings at Salon des Indépendants.[22] In this exhibition Metzinger is directly associated with the artists soon to be known as Fauves: Camoin, Delaunay, Derain, van Dongen, Dufy, Friesz, Manguin, Marquet, Matisse, Valtat, Vlaminck and others. Matisse was in charge of the hanging committee, assisted by Metzinger, Bonnard, Camoin, Laprade Luce, Manguin, Marquet, Puy and Vallotton.[23]

In 1906 Metzinger exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants.[24] Once again he was elected member of the hanging committee, with Matisse, Signac and others. Again with the Fauves and associated artists, Metzinger exhibited at the 1906 Salon d'Automne, Paris. He exhibited six works at the 1907 Salon des Indépendants, followed by the presentation of two works at the 1907 Salon d'Automne.[23][25]

In 1906 Metzinger met Albert Gleizes at the Salon des Indépendants, and visited his studio in Courbevoie several days later. In 1907, at Max Jacob's room, Metzinger met Guillaume Krotowsky, who already signed his works Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1908 a poem by Metzinger, Parole sur la lune, was published in Guillaume Apollinaire's La Poésie Symboliste.[26]

From 21 December 1908 to 15 January 1909, Metzinger exhibited at the gallery of Wilhelm Uhde, rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs (Paris) with Georges Braque, Sonia Delaunay, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Auguste Herbin, Jules Pascin and Pablo Picasso.[27]

1908 continued with the Salon de la Toison d'Or, Moscow. Metzinger exhibited five paintings with Braque, Derain, van Dongen, Friesz, Manguin, Marquet, Matisse, Puy, Valtat and others. At the 1909 Salon d’Automne Metzinger exhibited alongside Constantin Brâncuși, Henri Le Fauconnier and Fernand Léger.[23]

Jean Metzinger married Lucie Soubiron in Paris on 30 December of the same year.[17]

Neo-Impressionism, Divisionism

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_72.5_x_100_cm%252C_Rijksmuseum_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller%252C_Otterlo%252C_Netherlands.jpg.webp)

By 1903, Metzinger was a keen participant in the Neo-Impressionist revival led by Henri-Edmond Cross. By 1904–05, Metzinger began to favor the abstract qualities of larger brushstrokes and vivid colors. Following the lead of Seurat and Cross, he began incorporating a new geometry into his works that would free him from the confines of nature as much as any artwork executed in Europe to date.[28] The departure from naturalism had only just begun. Metzinger, along with Derain, Delaunay, Matisse, between 1905 and 1910, helped revivify Neo-Impressionism, albeit in a highly altered form. In 1906 Metzinger had acquired enough prestige to be elected to the hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants. He formed a close friendship at this time with Robert Delaunay, with whom he shared an exhibition at Berthe Weill early in 1907. The two of them were singled out by one critic (Louis Vauxcelles) in 1907 as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like 'cubes' to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[29]

Robert Herbert writes: "Metzinger's Neo-Impressionist period was somewhat longer than that of his close friend Delaunay. At the Indépendants in 1905, his paintings were already regarded as in the Neo-Impressionist tradition by contemporary critics, and he apparently continued to paint in large mosaic strokes until some time in 1908. The height of his Neo-Impressionist work was in 1906 and 1907, when he and Delaunay did portraits of each other (Art market, London, and Museum of Fine Arts Houston) in prominent rectangles of pigment. (In the sky of Coucher de soleil, 1906–1907, Collection Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller is the solar disk which Delaunay was later to make into a personal emblem.)"[30][31]

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_73_x_54_cm_DSC05359...jpg.webp)

The vibrating image of the sun in Metzinger's painting, and so too of Delaunay's Paysage au disque (1906–1907), "is an homage to the decomposition of spectral light that lay at the heart of Neo-Impressionist color theory...".[30][33][34]

Jean Metzinger's mosaic-like Divisionist technique had its parallel in literature; a characteristic of the alliance between Symbolist writers and Neo-Impressionist artists:

I ask of divided brushwork not the objective rendering of light, but iridescences and certain aspects of color still foreign to painting. I make a kind of chromatic versification and for syllables I use strokes which, variable in quantity, cannot differ in dimension without modifying the rhythm of a pictorial phraseology destined to translate the diverse emotions aroused by nature. (Jean Metzinger, circa 1907)[35]

Robert Herbert interprets Metzinger's statement: "What Metzinger meant is that each little tile of pigment has two lives: it exists as a plane whose mere size and direction are fundamental to the rhythm of the painting and, secondly, it also has color which can vary independently of size and placement. This is only a degree beyond the preoccupations of Signac and Cross, but an important one. Writing in 1906, Louis Chassevent[36] recognized the difference, and as Daniel Robbins pointed out in his Gleizes catalogue, used the word "cube" which later would be taken up by Louis Vauxcelles to baptize Cubism: "M. Metzinger is a mosaicist like M. Signac but he brings more precision to the cutting of his cubes of color which appear to have been made mechanically". The interesting history of the word "cube" goes back at least to May 1901 when Jean Béral, reviewing Cross's work at the Indépendants in Art et Littérature, commented that he "uses a large and square pointillism, giving the impression of mosaic. One even wonders why the artist has not used cubes of solid matter diversely colored: they would make pretty revetments."[30]

Metzinger, followed closely by Delaunay—the two often painting together, 1906–07—developed a new sub-style that had great significance shortly thereafter within the context of their Cubist works. Piet Mondrian, in the Netherlands, developed a similar mosaic-like Divisionist technique circa 1909. The Futurists later (1909–1916) would adapt the style, thanks to Gino Severini's Parisian experience (from 1907 onward), into their dynamic paintings and sculpture.[30]

In 1910 Gelett Burgess writes in The Wild Men of Paris: "Metzinger once did gorgeous mosaics of pure pigment, each little square of color not quite touching the next, so that an effect of vibrant light should result. He painted exquisite compositions of cloud and cliff and sea; he painted women and made them fair, even as the women upon the boulevards fair. But now, translated into the idiom of subjective beauty, into this strange Neo-Classic language, those same women, redrawn, appear in stiff, crude, nervous lines in patches of fierce color."[37]: 3

"Instead of copying Nature," Metzinger explained circa 1909, "we create a milieu of our own, wherein our sentiment can work itself out through a juxtaposition of colors. It is hard to explain it, but it may perhaps be illustrated by analogy with literature and music. Your own Edgar Poe (he pronounced it ‘Ed Carpoe’) did not attempt to reproduce Nature realistically. Some phase of life suggested an emotion, as that of horror in ‘The Fall of the House of Ushur.’ That subjective idea he translated into art. He made a composition of it."

"So, music does not attempt to imitate Nature’s sounds, but it does interpret and embody emotions awakened by Nature through a convention of its own, in a way to be aesthetically pleasing. In some such way, we, taking out hint from Nature, construct decoratively pleasing harmonies and symphonies of color expression of our sentiment." (Jean Metzinger, c. 1909, The Wild Men of Paris, 1910)[37]

Cubism

%252C_illustrated_in_Gelett_Burgess%252C_The_Wild_Men_of_Paris%252C_The_Architectural_Record%252C_Document_3%252C_May_1910%252C_New_York%252C_location_unknown.jpg.webp)

By 1907 several avant-garde artists in Paris were reevaluating their own work in relation to that of Paul Cézanne. A retrospective of Cézanne's paintings had been held at the Salon d'Automne of 1904. Current works were displayed at the 1905 and 1906 Salon d'Automne, followed by two commemorative retrospectives after his death in 1907. Metzinger's interest in the work of Cézanne suggests a means by which Metzinger made the transformation from Divisionism to Cubism. In 1908 Metzinger frequented the Bateau Lavoir and exhibited with Georges Braque at Berthe Weill's gallery.[38] By 1908 Metzinger experimented with the fracturing of form, and soon thereafter with complex multiple views of the same subject.

A critic wrote of Metzinger's work exhibited during the spring of 1909:

If M. J. Metzinger had really realized the "Nude" that we see at Madame Weill's, and wished to demonstrate the value of his work, the schematic figure that he shows us would serve this demonstration. As such, it is a skeletal frame without its flesh; this is better than flesh without a skeletal frame: the spirit at least finds some security. But this excess of abstraction interests us much more than possesses us.[39]

Metzinger's early 1910 style had transited to a robust form of analytical Cubism.[19][38]

Louis Vauxcelles, in his review of the 26th Salon des Indépendants (1910), made a passing and imprecise reference to Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Léger and Le Fauconnier, as "ignorant geometers, reducing the human body, the site, to pallid cubes."[19][40]

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92_x_66_cm%252C_Gothenburg_Museum_of_Art%252C_Sweden.jpg.webp)

In 1910 a group began to form which included Metzinger, Gleizes, Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay, a longstanding friend and associate of Metzinger. They met regularly at Henri le Fauconnier's studio on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, near the boulevard du Montparnasse. Together with other young painters, the group wanted to emphasize a research into form, in opposition to the Divisionist, or Neo-Impressionist, emphasis on color. Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Delaunay, Léger and Marie Laurencin were shown together in Room 41 of the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, which provoked the 'involuntary scandal' out of which Cubism emerged and spread in Paris, in France and throughout the world. Laurencin was included at the suggestion of Guillaume Apollinaire who had become an enthusiastic supporter of the new group despite his earlier reservations. Both Metzinger and Gleizes were discontent with the conventional perspective, which they felt gave only a partial idea of a subject's form as experienced in life.[41] The idea that a subject could be seen in movement and from many different angles was born.[19]

In Room 7 and 8 of the 1911 Salon d'Automne (1 October – 8 November) at the Grand Palais in Paris, hung works by Metzinger (Le goûter (Tea Time)), Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Albert Gleizes, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp, František Kupka and Francis Picabia. The result was a public scandal which brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the second time. Apollinaire took Picasso to the opening of the exhibition in 1911 to see the cubist works in Room 7 and 8.[42]

While Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque are generally acknowledged as the founders of the twentieth-century movement that became known as Cubism, it was Jean Metzinger, together with Albert Gleizes, that created the first major treatise on the new art-form, Du "Cubisme", in preparation for the Salon de la Section d'Or held in October 1912. Du "Cubisme", published the same year by Eugène Figuière in Paris,[43] represented the first theoretical interpretation, elucidation and justification of Cubism, and was endorsed by both Picasso and Braque. Du "Cubisme", which preceded Apollinaire's well known essays, Les Peintres Cubistes (published 1913), emphasized the Platonic belief that the mind is the birthplace of the idea: "to discern a form is to verify a pre-existing idea",[44][45] and that "The only error possible in art is imitation" [La seule erreur possible en art, c'est l'imitation].[46]

Du "Cubisme" quickly gained popularity running through fifteen editions the same year and translated into several European languages including Russian and English (the following year).

In 1912 Metzinger was the leading figure in the first exhibition of Cubism in Spain[47] at Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona, with Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Henri Le Fauconnier, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin, and August Agero.[48][49][50]

In 1913, Apollinaire wrote in Les Peintres Cubistes:

In drawing, in composition, in the judiciousness of contrasted forms, Metzinger's works have a style which sets them apart from, and perhaps even above most of the works of his contemporaries... It was then that Metzinger, joining Picasso and Braque, founded the Cubist City... There is nothing unrealized in the art of Metzinger, nothing which is not the fruit of a rigorous logic. A painting by Metzinger always contains its own explanation ... it is certainly the result of great hindmindedness and is something unique it seems to me, in the history of art.

Apollinaire continues:

The new structures he is composing are stripped of everything that was known before him... Each of his paintings contains a judgement of the universe, and his work is like the sky at night: when, cleared of the clouds, it trembles with lovely lights. There is nothing unrealized in Metzinger's works: poetry ennobles their slightest details.[51]

Jean Metzinger, through the intermediary of Max Jacob, met Apollinaire in 1907. Metzinger's 1909–10 Portrait de Guillaume Apollinaire, is as important a work in the history of Cubism as it was in Apollinaire's own life. In his Anecdotiques of 16 October 1911, the poet proudly states: "I am honored to be the first model of a Cubist painter, Jean Metzinger, for a portrait exhibited in 1910 at the Salon des Indépendants." So according to Apollinaire it was not only the first cubist portrait, but it was also the first great portrait of the poet exhibited in public.[52]

Two works directly preceding Apollinaire's portrait, Nu and Landscape, circa 1908 and 1909 respectively, indicate that Metzinger had already departed from Divisionism by 1908. Turning his attention fully towards the geometric abstraction of form, Metzinger allowed the viewer to reconstruct the original volume mentally and to imagine the object within space. His concerns for color that had assumed a primary role both as a decorative and expressive device before 1908 had given way to the primacy of form. But his monochromatic tonalities would last only until 1912, when both color and form would boldly combine to produce such works as Dancer in a café (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo New York). "The works of Jean Metzinger" Apollinaire writes in 1912 "have purity. His meditations take on beautiful forms whose harmony tends to approach sublimity. The new structures he is composing are stripped of everything that was known before him."

As a resident of la Butte Montmartre in Paris, Metzinger entered the circle of Picasso and Braque (in 1908). "It is to the credit of Jean Metzinger, at the time, to have been the first to recognize the commencement of the Cubist Movement as such" writes S. E. Johnson, "Metzinger's portrait of Apollinaire, the poet of the Cubist Movement, was executed in 1909 and, as Apollinaire himself has pointed out in his book The Cubist Painters (written in 1912 and published in 1913), Metzinger, following Picasso and Braque, was chronologically the third Cubist artist.[53]

Crystal Cubism

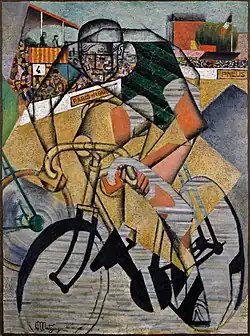

Metzinger's evolution toward synthesis in 1914–15 has its origins in the configuration of flat squares, trapezoidal and rectangular planes that overlap and interweave, a "new perspective" in accord with the "laws of displacement".[19] In the case of Le Fumeur Metzinger filled in these simple shapes with gradations of color, wallpaper-like patterns and rhythmic curves. So too in Au Vélodrome. But the underlying armature upon which all is built is palpable. Vacating these non-essential features would lead Metzinger on a path towards Soldier at a Game of Chess (1914–15), and a host of works created after the artist's demobilization as a medical orderly during the war, such as L'infirmière (The Nurse) location unknown, and Femme au miroir, private collection.[19]

Before Maurice Raynal coined the term Crystal Cubism, one critic by the name of Aloës Duarvel, writing in L'Élan, referred to Metzinger's entry exhibited at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune (28 December 1915 – 15 January 1916) as 'jewellery' ("joaillerie").[54]

For Metzinger, the Crystal period was synonymous with a return to "a simple, robust art".[55] Crystal Cubism represented an opening up of possibilities.[56] His belief was that technique should be simplified and that the "trickery" of chiaroscuro should be abandoned, along with the "artifices of the palette".[55] He felt the need to do without the "multiplication of tints and detailing of forms without reason, by feeling":[55]

Eventually all the Cubists (except for Gleizes, Delaunay and a handful of others) would return to some form of classicism at the end of World War I. Even so, the lessons of Cubism would not be forgotten.

Metzinger's apparent departure from Cubism circa 1918 would leave open the "spatial" susceptibility to classical observation, but the "form" could only be grasped by the "intelligence" of the observer, something that escaped classical observation.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_90.7_x_64.2_cm%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum.jpg.webp)

In a letter to Léonce Rosenberg (September 1920) Jean Metzinger wrote of a return to nature that appeared to him both constructive and not at all a renunciation of Cubism. His exhibition at l'Effort Moderne at the outset of 1921 was exclusively of landscapes: his formal vocabulary remained rhythmic, linear perspective was avoided. There was a motivation to unite the pictorial and the natural. Christopher Green writes: "The willingness to adapt Cubist language to the look of nature was quickly to affect his figure painting too. From that exhibition of 1921 Metzinger continued to cultivate a style that was not only less obscure, but clearly took subject-matter as its starting point far more than an abstract play with flat pictorial elements." Green continues:

Yet, style, in the sense of his own special way of handling form and color, remained for Metzinger the determining factor, something imposed on his subjects to give them their special pictorial character. His sweet, rich colour between 1921 and 1924 was unashamedly artificial, and is itself symptomatic of the fact that his return to lucid representation did not mean a return to nature approached naturalistically... Metzinger himself, writing in 1922 [published by Montparnasse] could claim quite confidently that this was not at all a betrayal of Cubism but a development within it. 'I know works,' he said, 'whose thoroughly classical appearance conveys the most personal [the most original] the newest conceptions... Now that certain Cubists have pushed their constructions so far as to take in clearly objective appearances, it has been declared that Cubism is dead [in fact] it approaches realization.'[57][58]

The strict constructive ordering that had become so pronounced in Metzinger's pre-1920 Cubist works continued throughout the subsequent decades, in the careful positioning of form, color, and in the way in which Metzinger delicately assimilates the union of figure and background, of light and shadow. This can be seen in many figures: From the division (in two) of the model's features emerges a subtle profile view—resulting from a free and mobile perspective used by Metzinger to some extent as early as 1908 to constitute the image of a whole—one that includes the fourth dimension.[59]

Both as a painter and theorist of the Cubist movement, Metzinger was at the forefront. It was too Metzinger's role as a mediator between the general public, Picasso, Braque and other aspiring artists (such as Gleizes, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier and Léger) that places him directly at the center of Cubism. Daniel Robbins writes:

Jean Metzinger was at the center of Cubism, not only because of his role as intermediary among the orthodox Montmartre group and right bank or Passy Cubists, not only because of his great identification with the movement when it was recognized, but above all because of his artistic personality. His concerns were balanced; he was deliberately at the intersection of high intellectuality and the passing spectacle.[6]

Theory

_oil_on_canvas%252C_230_x_196_cm%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Art_Moderne_de_la_Ville_de_Paris..jpg.webp)

Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes wrote with reference to non-Euclidean geometry in their 1912 manifesto, Du "Cubisme". It was argued that Cubism itself was not based on any geometrical theory, but that non-Euclidean geometry corresponded better than classical, or Euclidean geometry, to what the Cubists were doing. The essential was in the understanding of space other than by the classical method of perspective; an understanding that would include and integrate the fourth dimension with 3-space.[60]

Though the rupture with the past seemed total, there was still within the avant-garde something of the past. Metzinger, for example, writes in a Pan article, two years before the publication of Du "Cubisme", that the greatest challenge to the modern artist is not to 'cancel' tradition, but to accept "it is in us," acquired by living. It was the combination of the past (himself inspired by Ingres and Seurat) with the present, and its progression into the future that most intrigued Metzinger. Observed was the tendency; a "balance between the pursuit of the transient and the mania for the eternal. But the result would be an unstable equilibrium. The domination would no longer be of the external world. The progression was from the specific to the universal, from the special to the general, from the physical to the temporary, towards a complete synthesis of the whole—however unattainable—towards an 'elemental common denominator' (to use the words of Daniel Robbins).[19]

Whereas Cézanne had been influential to the development of Metzinger's Cubism between 1908 and 1911, during its most expressionistic phase, the work of Seurat would once again attract attention from the Cubists and Futurists between 1911 and 1914, when flatter geometric structures were being produced. What the Cubists found attractive, according to Apollinaire, was the manner in which Seurat asserted an absolute "scientific clarity of conception." The Cubists observed in his mathematical harmonies, geometric structuring of motion and form, the primacy of idea over nature (something the Symbolists had recognized). In their eyes, Seurat had "taken a fundamental step toward Cubism by restoring intellect and order to art, after Impressionism had denied them" (to use the words of Herbert). The "Section d'Or" group founded by some of the most prominent Cubists was in effect an homage to Seurat. Within the works by Seurat—of cafés, cabarets and concerts, of which the avant-garde were fond—the Cubists' discovered an underlying mathematical harmony: one that could easily be transformed into mobile, dynamical configurations.[30]

The idea of moving around an object in order to see it from different view-points is treated in Du "Cubisme" (1912). It was also a central idea of Jean Metzinger's Note sur la Peinture, 1910; Indeed, prior to Cubism painters worked from the limiting factor of a single view-point. And it was Jean Metzinger, for the first time in Note sur la peinture who enunciated the stimulating interest in representing objects as remembered from successive and subjective experiences within the context of both space and time. In that article, Metzinger notes that Braque and Picasso "discarded traditional perspective and granted themselves the liberty of moving around objects." This is the concept of "mobile perspective" that would tend towards the representation of the "total image."[5]

Metzinger's Note sur la peinture not only highlighted the works of Picasso and Braque, on the one hand, Le Fauconnier and Delaunay on the other, but it was also a tactical selection that highlighted the fact that only Metzinger himself was positioned to write about all four. Metzinger, uniquely, had been closely acquainted with the gallery cubists and the burgeoning salon cubists simultaneously.[61]

Though the idea of moving around objects to capture several angles at the same time would shock the public they eventually came to accept it, as they came to accept the 'atomist' representation of the universe as a multitude of dots consisting of primary colors. Just as each color is modified by its relation to adjacent colors within the context of Neo-Impressionist color theory, so too the object is modified by the geometric forms adjacent to it within the context of Cubism. The concept of 'mobile perspective' is essentially an extension of a similar principle stated in Paul Signac's D'Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionisme, with respect to color. Only now, the idea is extended to deal with questions of form.[30] (See Jean Metzinger, 1912, Dancer in a café[62]).

Cubism by 1912 had abstracted almost to the point of total non-representation. In Du "Cubisme" Metzinger and Gleizes had realized that figurative aspects of the new art could be abandoned:

"we visit an exhibition to contemplate painting, not to enlarge our knowledge of geography, anatomy etc. [...] 'Let the picture imitate nothing; let it nakedly present its motive, and we should indeed be ungrateful were we to deplore the absence of all those things – flowers or landscapes or faces – of which it could never have been anything other than a reflection'. Though Metzinger and Gleizes hesitate to do away with nature entirely: 'Nevertheless, let us admit that the reminiscence of natural forms cannot be absolutely banished; as yet, at all events. An art cannot be raised all at once to the level of a pure effusion.' [...] 'This is understood by the Cubist painters, who tirelessly study pictorial form and the space which it engenders'.[63]

%252C_129.7_x_96.68_cm%252C_Carnegie_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp)

One of the essential arguments of Du "Cubisme", was that knowledge of the world is to be gained through 'sensations' alone. Classical figurative painting offered only one point of view, a restrained 'sensation' of the world, limited to the sensation of a motionless human being who sees only that which is in front of him from a single point in space frozen in a moment of time (time was absolute in the Newtonian sense and separate from the spatial dimensions). But the human being is mobile and dynamic, occupying both space and to time. The observer sees the world from a multitude of angles (not one unique angle) forming a continuum of sensations in constant evolution, i.e., events and natural phenomena are observed in a continuum of constant change. Just as the formulations of Euclidean geometry, classical perspective is only a 'convention' (Henri Poincaré's term), rendering the phenomena of nature more palpable, susceptible to thought and understandable. Yet these classical conventions obscured the truth of our sensations, and consequently, the truth of our own human nature was limited. The world was seen as an abstraction, as Ernst Mach implied. In this sense, it could be argued that classical painting, with its immobile perspective and Euclidean geometry, was an abstraction, not an accurate representation of the real world.

What made Cubism progressive and truly modern, according to Metzinger and Gleizes, was its new geometric armature; with that it broke free from the immobility of 3-dimensional Euclidean geometry and attained a dynamic representation of the 4-dimensional continuum in which we live, a better representation of reality, of life's experience, something that could be grasped through the senses (not through the eye) and expressed onto a canvas.

In Du "Cubisme" Metzinger and Gleizes write that we can only know our sensations, not because they reject them as a means of inspiration. On the contrary, because understanding our sensations more deeply gave them the primary inspiration for their own work. Their attack on classical painting was leveled precisely because the sensations it offered were poor in comparison with the richness and diversity of the sensations offered by the natural world it wished to imitate. The reason classical painting fell short of its goal, according to Metzinger and Gleizes, is that it attempted to represent the real world as a moment in time, in the belief that it was 3-dimensional and geometrically Euclidean.[64]

Scientific aspects

The question of whether the theoretical aspects of Cubism enunciated by Metzinger and Gleizes bore any relation to the development in science at the beginning of the twentieth century has been vigorously disputed by art critics, historians and scientists alike. Yet in Du "Cubisme" Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes articulate: "If we wished to relate the space of the [Cubist] painters to geometry, we should have to refer it to the non-Euclidean mathematicians; we should have to study, at some length, certain of Riemann's theorems."

There was, after all, little to prevent the Cubists from developing their own pictorial variants on the topological space in parallel to (or independently of) relativistic considerations. Though the concept of observing a subject from different points in space and time simultaneously (multiple or mobile perspective) developed by Metzinger and Gleizes was not derived directly from Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, it was certainly influenced in a similar way, through the work of Jules Henri Poincaré (particularly Science and Hypothesis), the French mathematician, theoretical physicist and philosopher of science, who made many fundamental contributions to algebraic topology, celestial mechanics, quantum theory and made an important step in the formulation of the theory of special relativity.

A multitude of analogies, similarities or parallels have been drawn over the decades between modern science and Cubism. But there has not always been agreement as to how the writings of Metzinger and Gleizes should be interpreted, with respect to 'simultaneity' of multiple view-points.

Metzinger had already written in 1910 of 'mobile perspective', as an interpretation of what would soon be dubbed "Cubism" with respect to Picasso, Braque, Delaunay and Le Fauconnier (Metzinger, "Note sur la peinture", Pan, Paris, Oct–Nov 1910). And Apollinaire would echo the same tune a year later regarding the observer's state of motion. Mobile perspective was akin to "cinematic" movement around an object that consisted of a plastic truth compatible with reality by showing the spectator "all its facets." Gleizes too, the same year, remarks, Metzinger is "haunted by the desire to inscribe a total image [...] He will put down the greatest number of possible planes: to purely objective truth he wishes to add a new truth, born from what his intelligence permits him to know. Thus—and he said himself: to space he will join time. [...] he wishes to develop the visual field by multiplying it, to inscribe them all in the space of the same canvas: it is then that the cube will play a role, for Metzinger will utilize this means to reestablish the equilibrium that these audacious inscriptions will have momentarily broken."[19]

Poincaré's writings, unlike Einstein's, were well known leading up to and during the crucial years of the Cubism (roughly between 1908 and 1914). Note that Poincaré's widely read book, La Science et l'Hypothèse, was published in 1902 (by Flammarion).

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_81.3_x_61_cm%252C_Smart_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp)

The common denominator between the special relativistic notions—the lack an absolute reference frame, metric transformations of the Lorentzian type, the relativity of simultaneity, the incorporation of the time dimension with three spatial dimensions—and the Cubist idea of mobile perspective (observing the subject from several view-points simultaneously) published by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes was, in effect, a descendant from the work of Poincaré and others, at least from the theoretical standpoint. Whether the concept of mobile perspective accurately describes the work of Picasso and Braque (or other Cubists') is certainly debatable. Undoubtedly though, both Metzinger and Gleizes implemented the theoretical principles derived in Du "Cubisme" onto canvas; something clearly visible in their works produced at the time.

Metzinger's early interests in mathematics are documented. He was likely familiar with the works of Gauss, Riemann and Poincaré (and perhaps Galilean relativity) prior to the development of Cubism: something that reflects in his pre-1907 works. It was perhaps the French mathematician Maurice Princet who introduced the work of Poincaré, along with the concept of the fourth spatial dimension, to artists at the Bateau-Lavoir. He was a close associate of Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Jean Metzinger and Marcel Duchamp. Princet is known as "le mathématicien du cubisme." Princet brought to attention of these artists a book entitled Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions by Esprit Jouffret (1903) a popularization of Poincaré's Science and Hypothesis. In this book Jouffret described hypercubes and complex polyhedra in four dimensions projected onto a two-dimensional page. Princet became estranged from the group after his wife left him for André Derain. However, Princet would remain close to Metzinger and participate in meetings of the Section d'Or in Puteaux. He gave informal lectures to the artists, many of whom were passionate about mathematical order. In 1910, Metzinger said of him, "[Picasso] lays out a free, mobile perspective, from which that ingenious mathematician Maurice Princet has deduced a whole geometry".[5]

Later, Metzinger wrote in his memoirs (Le Cubisme était né):

Maurice Princet joined us often. Although quite young, thanks to his knowledge of mathematics he had an important job in an insurance company. But, beyond his profession, it was as an artist that he conceptualized mathematics, as an aesthetician that he invoked n-dimensional continuums. He loved to get the artists interested in the new views on space that had been opened up by Schlegel and some others. He succeeded at that.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92.4_x_65.1_cm%252C_private_collection.jpg.webp)

Louis Vauxcelles sarcastically dubbed Princet "the father of cubism":

M. Princet has studied at length non-Euclidean geometry and the theorems of Riemann, of which Gleizes and Metzinger speak... Princet one day met M. Max Jacob and confided him one or two of his discoveries relating to the fourth dimension. M. Jacob informed the ingenious Picasso of it, and Picasso saw there a possibility of new ornamental schemes. Picasso explained his intentions to Apollinaire, who hastened to write them up in formularies and codify them. The thing spread and propagated. Cubism, the child of M. Princet, was born. (Vauxcelles, December 29, 1918).[66]

In addition to mathematics, both human sensation and intelligence were important to Metzinger. It was lack of the latter human attribute that the principle theorists of Cubism were to reproach the Impressionists and Fauves, for whom sensation was the sole necessity. Intelligence had to work in harmony with sensation, thus together providing the building blocks for the Cubists construction. Metzinger, with his mathematical education and prowess had realized this relation early on. Indeed, the geometrization of space that would characterize Cubism can already be observed in his works as early as 1905, following the lead of Seurat and Cézanne. (See Jean Metzinger, 1905–1906, Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape, oil on canvas, 116 x 88.8 cm).

For Metzinger, along with to some extent both Gleizes and Malevich, the classical vision had been an incomplete representation of real things, based on an incomplete set of laws, postulates and theorems. It represented, quite simply, the belief that space is the only thing that separates two points. It was the belief in the geocentric reality of the observable world, unchanging and immobile. The Cubists had been delighted to discover that the world was in reality dynamic, changing in time, it appeared different depending on the point of view of the observer. And yet each one of these viewpoints were equally valid, there was no preferred reference frame, all reference frames were equal. This underlying symmetry inherent in nature, in fact, is the essence of Einstein's relativity.

Influence on quantum mechanics

On the question as to whether creativity in the domain of science has ever been influenced by art, Arthur I. Miller, author of Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time and the Beauty that Causes Havoc (2002), answers: "Cubism directly helped Niels Bohr discover the principle of complementarity in quantum theory, which says that something can be a particle and a wave at the same time, but it will always be measured to be either one or the other. In analytic cubism, artists tried to represent a scene from all possible viewpoints on one canvas. [...] How you view the painting, that’s the way it is. Bohr read the book by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes on cubist theory, Du "Cubisme". It inspired him to postulate that the totality of an electron is both a particle and a wave, but when you observe it you pick out one particular viewpoint."[68]

Niels Bohr (1885–1962), the Danish physicist and one of the principle founders of quantum mechanics, had hung in his office a large painting by Jean Metzinger, La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a horse) 1911–12 (now in the Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark). This work is one of Metzinger's most conspicuous early examples of 'mobile perspective' implementation. Bohr's interest in Cubism, according to Miller, was anchored in the writings of Metzinger. Arthur Miller concludes: "If cubism is the result of the science in Art, the quantum theory is the result of art in science."[69]

In the epistemological words of Bohr, 1929:

...depending upon our arbitrary point of view...we must, in general, be prepared to accept the fact that a complete elucidation of one and the same object may require diverse points of view which defy a unique description. (Niels Bohr, 1929)[70]

Within the context of Cubism, artists were forced into the position of re-evaluating the role of the observer. Classical linear and aerial perspective, uninterrupted surface transitions and chiaroscuro were pushed aside. What remained was a series of images obtained by the observer (the artist) in different frames of reference as the object was being painted. Essentially, observations became linked through a system of coordinate transformations. The result was Metzinger's 'total image' or a combination of successive images. In Metzinger's theory, the artist and the object being observed became equivocally linked so that the results of any observation seemed to be determined, at least partially, by actual choices made by the artist. "An object has not one absolute form; it has many," Metzinger wrote. Furthermore, part of the role of placing together various images was left to the observer (the one looking at the painting). The object represented, depending on how the observer perceives it, could have as many forms "as there are planes in the region of perception." (Jean Metzinger, 1912)[71]

Exhibitions, students and later work

On 19 June 1916 Metzinger signed a three-year contract (later renewed for 15 years) with the dealer, art collector and gallery owner Léonce Rosenberg.[13] The agreement gave full rights for exhibitions and sales of Metzinger's production to Rosenberg. The contract fixed the prices of Metzinger's works bought by Rosenberg, who agreed to purchase a certain number of works (or a fixed value) every month. A contract between the two dated 1 January 1918 modified the first contract; the engagement was now renewable every two years, and prices of Metzinger's works purchased by Rosenberg increased.[13]

In 1923 Metzinger moved away from Cubism towards realism, while still retaining elements of his earlier Cubist style. In subsequent stages of his career another important change is noticeable, from 1924 to 1930: a development that paralleled the 'mechanical world' of Fernand Léger. Throughout these years Metzinger continued to retain his own marked artistic individuality. These firmly constructed pictures are brightly colored and visually metaphoric, consisting of urban and still-life subject-matter, with clear references to science and technology. At the same time he was romantically involved with a young Greek woman, Suzanne Phocas. The two were married in 1929. After 1930, until his death in 1956, Metzinger turned towards a more classical or decorative approach to painting with elements of Surrealism, still concerned with questions of form, volume, dimension, relative position and relationship of figures, along with visible geometric properties of space. Metzinger was commissioned to paint a large mural, Mystique of Travel, which he executed for the Salle de Cinema in the railway pavilion of the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris 1937.[72]

Jean Metzinger had been appointed to teach at the Académie de La Palette, in Paris, 1912, where Le Fauconnier served as director. Among his many students were Serge Charchoune, Jessica Dismorr, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Varvara Stepanova, Aristarkh Lentulov, Vera Efimovna Pestel and Lyubov Popova.[72][73] In 1913 Metzinger taught at the Académie Arenius and Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He later moved to Bandol in Provence where he lived until 1943 and then returned to Paris where he was given a teaching post for three years at the Académie Frochot in 1950. In Paris, 1952, he taught New Zealand artist Louise Henderson, who became one of the leading Modernist painters in Auckland upon her return.[74]

In 1913 Metzinger exhibited in New York City at the Exhibition of Cubist and Futurist Pictures, Boggs & Buhl Department Store, Pittsburgh. The show traveled to four other cities; Milwaukee, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, over the course of one year.[75] The Milwaukee exhibition of Cubist works—including paintings by Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp and Jacques Villon—opened 11 May 1913.[75] Metzinger's Man with a Pipe was reproduced on the cover of catalogue for the exhibition. Though he did not exhibit with his Cubist colleagues at the Armory Show of 1913, Metzinger contributed, through this exhibition and others, toward the integration of modern art into the United States.[75]

During the spring of 1916 Metzinger participated in one of the largest exhibitions of modern art in New York City organized by Walter Pach and a group of European and American artists in New York; The Annual Exhibition of Modern Art, held at Bourgeois Gallery. Initially, some American exhibitors were offended by the 'continental' nature of the show, but as Pack informed Matisse, "the petty nationalism that had one had tried to throw inside had failed to advance, and I am certain of that".[76] The exhibition included works by Cézanne, Matisse, Duchamp, Picasso, Seurat, Signac, van Gogh, Duchamp-Villon, in addition to works by Pach, the Italian-born American Futurist painter Joseph Stella, and other American artists.[76]

Metzinger again exhibited in New york at the Bourgeois Gallery for the occasion of the 1917 and 1919 Annual Exhibition of Modern Art.[77][78]

Further exhibitions: 6–31 January 1919 Metzinger had a solo exhibition at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, and again 1–25 February 1921,[79] in addition to participating in various group exhibitions. He would exhibit regularly at L'Effort Moderne throughout the 1920s. The same year he showed in New York with Jean Crotti, Marcel Duchamp, and Albert Gleizes at the Montross Gallery (where the Frenchmen became known as The Four Musketeers).[76] Among his solo exhibitions were those at the Leicester Galleries in London in 1930, the Hanover Gallery in London in 1932, the Arts Club of Chicago in 1953[80] (for which he traveled to the United States on the transatlantic ocean liner Le Flandre)[81] and International Galleries, Chicago, 1964. In 1985–1986, a retrospective of Metzinger's works, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, took place at The University of Iowa Museum of Art, and traveled to Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery University of Texas at Austin, The David Alfred Smart Gallery University of Chicago, and Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Metzinger, a sensitive and intelligent theoretician of Cubism, sought to communicate the principles of this movement through his paintings as well as his writings. (Lucy Flint, Peggy Guggenheim Collection)[82]

Many exhibitions document the painter's national and international success.[83] His works can be found in private and public collections and institutions around the world.

The artist died in Paris on November 3, 1956.[80]

Legacy

In the words of S.E. Johnson, an in-depth analysis of Metzinger's Pre-Cubist period—his first artistic peak—"can only class that painter, in spite of his youth, as being already one of the leading artistic personalities in that period directly preceding Cubism. [...] In an attempt to understand the importance of Jean Metzinger in Modern Art, we could limit ourselves to three considerations. Firstly, there is the often overlooked importance of Metzinger's Divisionist Period of 1900–1908. Secondly, there is the role of Metzinger in the founding of the Cubist School. Thirdly, there is the consideration of Metzinger's whole Cubist Period from 1909 to 1930. In taking into account these various factors, we can understand why Metzinger must be included among that small group of artists who have taken a part in the shaping of Art History in the first half of the Twentieth Century."[53]

Gallery

Jean Metzinger, c.1905-06, Nu dans un paysage, oil on canvas, 73 x 54 cm. 2nd Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler Sale of Sequestered Art, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 17–18 November 1921, reproduced n. 162

Jean Metzinger, c.1905-06, Nu dans un paysage, oil on canvas, 73 x 54 cm. 2nd Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler Sale of Sequestered Art, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 17–18 November 1921, reproduced n. 162%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_44.8_x_36.8_cm%252C_Korban_Art_Foundation..jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, c.1906, Femme au Chapeau (Woman with a Hat), oil on canvas, 44.8 x 36.8 cm, Korban Art Foundation

Jean Metzinger, c.1906, Femme au Chapeau (Woman with a Hat), oil on canvas, 44.8 x 36.8 cm, Korban Art Foundation%252C_oil_on_carton%252C_52_x_35_cm._Reproduced_in_Du_%22Cubisme%22%252C_1912.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Nu (Nu debout), oil on carton, 52 x 35 cm. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912

Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Nu (Nu debout), oil on carton, 52 x 35 cm. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912 Jean Metzinger, c.1911, Nature morte (Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs), oil on canvas, 93.5 by 66.5 cm, published in Nya Konstgalleriet, Flamman, Stockholm, 1917

Jean Metzinger, c.1911, Nature morte (Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs), oil on canvas, 93.5 by 66.5 cm, published in Nya Konstgalleriet, Flamman, Stockholm, 1917 Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Le Port (The Harbor). Exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, Paris. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, 1912, Paris, and Les Peintres Cubistes Guillaume Apollinaire, 1913. Dimensions and current location unknown

Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Le Port (The Harbor). Exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, Paris. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, 1912, Paris, and Les Peintres Cubistes Guillaume Apollinaire, 1913. Dimensions and current location unknown%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92.7_x_65.4_cm_(36.5_x_25.75_in)%252C_Lawrence_University%252C_Appleton%252C_Wisconsin.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoker), oil on canvas, 92.7 x 65.4 cm (36.5 x 25.75 in), Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin. Reproduced on the catalogue cover of Exhibition of Cubist and Futurist Pictures, Boggs & Buhl Department Store, Pittsburgh, July 1913

Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoker), oil on canvas, 92.7 x 65.4 cm (36.5 x 25.75 in), Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin. Reproduced on the catalogue cover of Exhibition of Cubist and Futurist Pictures, Boggs & Buhl Department Store, Pittsburgh, July 1913%252C_location_unknown._Reproduced_in_Du_%22Cubisme%22%252C_1912.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, c.1912, Paysage (Landscape). Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912

Jean Metzinger, c.1912, Paysage (Landscape). Reproduced in Du "Cubisme", 1912 Jean Metzinger, 1912, At the Cycle-Race Track (Au Vélodrome), oil and sand on canvas, 130.4 x 97.1 cm (51.4 x 38.25 in.) The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Jean Metzinger, 1912, At the Cycle-Race Track (Au Vélodrome), oil and sand on canvas, 130.4 x 97.1 cm (51.4 x 38.25 in.) The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_51.4_x_68.6_cm%252C_Fogg_Art_Museum%252C_Harvard_University.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, 1912, Landscape (Marine, Composition Cubiste), oil on canvas, 51.4 x 68.6 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University. Published in Herwarth Walden, Einblick in Kunst: Expressionismus, Futurismus, Kubismus (1917), Der Sturm, 1912 - 1917

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Landscape (Marine, Composition Cubiste), oil on canvas, 51.4 x 68.6 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University. Published in Herwarth Walden, Einblick in Kunst: Expressionismus, Futurismus, Kubismus (1917), Der Sturm, 1912 - 1917%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_59.2_x_73_cm%252C_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, 1912, Paysage (Landscape), oil on canvas, 59.2 x 73 cm, published in Der Sturm, 5 January 1921, Art Institute of Chicago

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Paysage (Landscape), oil on canvas, 59.2 x 73 cm, published in Der Sturm, 5 January 1921, Art Institute of Chicago Jean Metzinger, 1913, Etude pour L'Oiseau bleu (Study for The Blue Bird), watercolor, graphite and ink on paper, 37 x 29.5 cm, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

Jean Metzinger, 1913, Etude pour L'Oiseau bleu (Study for The Blue Bird), watercolor, graphite and ink on paper, 37 x 29.5 cm, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris%252C_published_in_l'Elan%252C_Number_9%252C_12_February_1916.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, c.1915, L'infirmière (The Nurse), work on paper, dimensions and whereabouts unknown. Published in l'Elan, Number 9, 12 February 1916

Jean Metzinger, c.1915, L'infirmière (The Nurse), work on paper, dimensions and whereabouts unknown. Published in l'Elan, Number 9, 12 February 1916 Jean Metzinger, 1916-1918, Fruit and a Jug on a Table, oil and sand on canvas, 115.9 x 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Published in Paul Erich Küppers, Der Kubismus; ein künstlerisches Formproblem unserer Zeit, 1920

Jean Metzinger, 1916-1918, Fruit and a Jug on a Table, oil and sand on canvas, 115.9 x 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Published in Paul Erich Küppers, Der Kubismus; ein künstlerisches Formproblem unserer Zeit, 1920

Press articles

%252C_published_in_The_Sun%252C_New_York%252C_28_April_1918.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Femme à sa toilette, Lady at her Dressing Table), The Sun, New York, Sunday 28 April 1918

Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Femme à sa toilette, Lady at her Dressing Table), The Sun, New York, Sunday 28 April 1918 Paintings by Albert Gleizes, 1910–11, Paysage, Landscape; Juan Gris (drawing); Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs. Published on the front page of El Correo Catalán, 25 April 1912

Paintings by Albert Gleizes, 1910–11, Paysage, Landscape; Juan Gris (drawing); Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs. Published on the front page of El Correo Catalán, 25 April 1912 (center) Jean Metzinger, c.1913, Le Fumeur (Man with Pipe), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; (left) Alexander Archipenko, 1914, Danseuse du Médrano (Médrano II), (right) Archipenko, 1913, Pierrot-carrousel, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Published in Le Petit Comtois, 13 March 1914

(center) Jean Metzinger, c.1913, Le Fumeur (Man with Pipe), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; (left) Alexander Archipenko, 1914, Danseuse du Médrano (Médrano II), (right) Archipenko, 1913, Pierrot-carrousel, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Published in Le Petit Comtois, 13 March 1914 Paintings by Fernand Léger, 1912, La Femme en Bleu, Woman in Blue, Kunstmuseum Basel; Jean Metzinger, 1912, Dancer in a café, Albright-Knox Art Gallery; and sculpture by Alexander Archipenko, 1912, La Vie Familiale, Family Life (destroyed). Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, n. 1529, 13 October 1912

Paintings by Fernand Léger, 1912, La Femme en Bleu, Woman in Blue, Kunstmuseum Basel; Jean Metzinger, 1912, Dancer in a café, Albright-Knox Art Gallery; and sculpture by Alexander Archipenko, 1912, La Vie Familiale, Family Life (destroyed). Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, n. 1529, 13 October 1912%252C_Jean_Metzinger%252C_(Le_Go%C3%BBter)%252C_Robert_Delaunay_(La_Tour_Eiffel)%252C_La_Veu_de_Catalunya%252C_1_February_1912.jpg.webp) Paintings by Henri Le Fauconnier, 1910–11, L'Abondance, Haags Gemeentemuseum; Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art; Robert Delaunay, 1910–11, La Tour Eiffel. Published in La Veu de Catalunya, 1 February 1912

Paintings by Henri Le Fauconnier, 1910–11, L'Abondance, Haags Gemeentemuseum; Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art; Robert Delaunay, 1910–11, La Tour Eiffel. Published in La Veu de Catalunya, 1 February 1912 Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Paysage (whereabouts unknown); Gino Severini, 1911, La danseuse obsedante; Albert Gleizes, 1912, l'Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony (Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud). Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, Sommaire du n. 1536, décembre 1912

Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Paysage (whereabouts unknown); Gino Severini, 1911, La danseuse obsedante; Albert Gleizes, 1912, l'Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony (Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud). Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, Sommaire du n. 1536, décembre 1912 Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs; Juan Gris, 1911, Study for Man in a Café; Marie Laurencin, c. 1911, Testa ab plechs; August Agero, sculpture, Bust; Juan Gris, 1912, Guitar and Glasses, or Banjo and Glasses. Published in Veu de Catalunya, 25 April 1912

Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs; Juan Gris, 1911, Study for Man in a Café; Marie Laurencin, c. 1911, Testa ab plechs; August Agero, sculpture, Bust; Juan Gris, 1912, Guitar and Glasses, or Banjo and Glasses. Published in Veu de Catalunya, 25 April 1912%252C_published_in_Le_Journal%252C_30_September_1911.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art. Published in Le Journal, 30 September 1911

Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art. Published in Le Journal, 30 September 1911 Paintings by Juan Gris, Bodegón; August Agero (sculpture); Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Deux Nus, Two Nudes, Gothenburg Museum of Art; Marie Laurencin (acrylic); Albert Gleizes, 1911, Paysage, Landscape. Published in La Publicidad, 26 April 1912

Paintings by Juan Gris, Bodegón; August Agero (sculpture); Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Deux Nus, Two Nudes, Gothenburg Museum of Art; Marie Laurencin (acrylic); Albert Gleizes, 1911, Paysage, Landscape. Published in La Publicidad, 26 April 1912 The "Cubists" Dominate Paris' Fall Salon, The New York Times, October 8, 1911. Reproduced are Picasso's 1908 Seated Woman (Meditation); Picasso in his studio; Metzinger's Baigneuses (1908–09); works by Derain, Matisse, Friesz, Herbin, and a photo of Braque

The "Cubists" Dominate Paris' Fall Salon, The New York Times, October 8, 1911. Reproduced are Picasso's 1908 Seated Woman (Meditation); Picasso in his studio; Metzinger's Baigneuses (1908–09); works by Derain, Matisse, Friesz, Herbin, and a photo of Braque Page from the periodical Fantasio, 15 October 1911, featuring Portrait de Jacques Nayral by Albert Gleizes (1911) and Le goûter (Tea Time) by Jean Metzinger (1911)

Page from the periodical Fantasio, 15 October 1911, featuring Portrait de Jacques Nayral by Albert Gleizes (1911) and Le goûter (Tea Time) by Jean Metzinger (1911)

Catalogue raisonné

The Jean Metzinger Catalogue Raisonné (or critical catalogue), researched and written by art historian Alexander Mittelmann, published by the nonprofit association Défense et promotion de l'œuvre de l'artiste Jean Metzinger, assembles and classifies the complete works of the artist (paintings, works on paper). It comprises historiography, documentation, and inventory, with bibliographic, iconographic commentary, technical and chronological analysis of Metzinger's life and work. In addition to the catalogue raisonné, the forthcoming Jean Metzinger Monograph is set to be released in three volumes; the first in-depth study on the artist.[84][85][86]

Commemoration

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of Du "Cubisme" by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, the Musée de La Poste in Paris presents a show entitled "Gleizes – Metzinger. Du cubisme et après" from 9 May to 22 September 2012. Over 80 paintings and drawings, along with documents, films and 15 works by other members of the Section d'Or group (Villon, Duchamp-Villon, Kupka, Le Fauconnier, Lhote, La Fresnaye, Survage, Herbin, Marcoussis, Archipenko...) are included in the show. A catalogue in French and English accompanies the event. A French postage stamp is issued representing works by Metzinger (L'Oiseau bleu, 1912–13) and Gleizes (Le Chant de Guerre, 1915). This is the first major exhibition of works by Metzinger in Europe since his death in 1956, and it is the first time that a museum has organized an exhibit showcasing both Metzinger and Gleizes together.[87][88]

Art market

On 6 November 2007, Metzinger's Paysage, c.1916–17, oil on canvas, 81.2 x 99.3 cm, sold for US$2.393 million at Christie's, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale.[89][90]

On 4 February 2020 the painting Le cycliste (1912) by Metzinger sold at Sotheby's London for £3.015 (US$3.926 million).[91] The sale represents a world record auction price for the artist. The oil on canvas with sand, measuring 100 x 81 cm, was purchased by a private American collector.[92]

Partial list of works

- Rose Flower in a Vase, 1902

- The Clearing (Clairière), c. 1903

- Landscape (Paysage), 1904, Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina

- The Low Tide (La Marée Basse), c. 1904

- Le Chemin a travers les champs, c. 1904

- The Sea Shore, Bord de mer (Le Mur Rose), 1904–05, Indianapolis Museum of Art

- La Tour de Batz au coucher du soleil, 1904–05

- Le Château de Clisson, 1904–05, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

- Jeune Fille au Fauteuil (Femme nue au chignon assise), 1905

- Neo-Impressionist Landscape (Paysage Neo-Impressionniste), 1905, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes

- Two Nudes in a Garden (Deux nus dans un jardin), 1905–06, University of Iowa Museum of Art

- Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape (Baigneuses: Deux nus dans un jardin exotique), 1905–06, Carmen Cervera Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

- Coucher de Soleil No. 1 (Landscape), c. 1906, Kröller-Müller Museum

- La danse (Bacchante), c. 1906, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Parc Montsouris, Morning (Matin au Parc Montsouris), 1906

- Nude (Nu), 1906, Norton Museum of Art

- Paysage coloré aux oiseaux exotiques, 1906, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Portrait of Delaunay (Portrait de Delaunay), 1906

- Woman with a Hat (Femme au Chapeau), 1906, Korban Art Foundation

- Tropical Landscape (Paysage Tropical), 1906–07

- Paysage coloré aux oiseaux aquatiques, 1907

- Bathers (Baigneuses), c. 1908

- Nude (Nu à la cheminée), 1910

- Portrait of Apollinaire (Portrait d'Apollinaire), 1910

- Two Nudes (Deux nus), 1910–11, Gothenburg Museum of Art

- Standing Nude (Nu debout), 1910–11, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

- Portrait of Madame Metzinger, 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Le goûter (Tea Time), 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoker), 1911–12

- Woman with a horse (La Femme au Cheval), 1911–12, Statens Museum for Kunst

- Sailboats (Scène du port), c. 1912, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art

- Landscape (Paysage), 1912, Art Institute of Chicago

- Portrait, 1912, Fogg Museum, Harvard University

- Landscape, Marine (Composition Cubiste), 1912, Fogg Museum, Harvard University

- Dancer in a café (Danseuse au café), 1912, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

- Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), 1912, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- La Plume Jaune (The Yellow Feather), 1912

- At the Cycle-Race Track (Au Vélodrome, Le cycliste), 1912, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

- The Bathers (Les Baigneuses), 1912–13, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- The Blue Bird (L'Oiseau bleu), 1913, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Portrait of Madame Metzinger, 1913, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- En Canot, Femme au Canot et à l'Ombrelle (Im Boot), 1913, Missing or destroyed

- Woman with a Fan (Femme à l'Éventail), 1913, Art Institute of Chicago

- Study for The Smoker (La fumeuse), 1913–14, Museum of Modern Art

- Soldier at a Game of Chess (Soldat jouant aux échecs), 1914–15, Smart Museum of Art

- Femme à la dentelle, 1916, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Fruit and a Jug on a Table, 1916, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Table by a window, 1917, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Still Life, 1918, Art Institute of Chicago

- Femme face et profil (Femme au verre), 1919, Musee National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- Woman with a Coffee Pot (La Femme à la cafetière), 1919, |Tate Gallery

- Still Life (Nature morte), 1919, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

- La Tricoteuse, 1919, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

- City Landscape, 1919–20, University of Iowa Museum of Art

- Still Life (Nature morte), 1921, Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Le Bal masque (Carnaval a Venise), 1922

- Embarkation of Harlequin (Arlequin), 1922–23

- Le Bal masqué, La Comédie Italienne, 1924

- Young woman with a guitar (Femme à la guitare), 1924, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Salome, 1924, private collection

- Equestrienne, 1924, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Composition allegorique, 1928–29, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Nautical still life, 1930, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

- Globe and Banjo, 1930, Art Institute of Chicago

- Nu au Soleil, 1935, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- The Bather, Nude (La Baigneuse, Nu), 1936–37

- Yachting, 1937

- Reclining Nude (Nu allongé), 1945–50

- The Green Dress (La robe verte), c. 1950, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Publications

- Note sur la peinture, Pan (Paris), n° 10, October–November 1910

- Cubisme et tradition, Paris Journal, 16 August 1911

- Alexandre Mercereau, Vers et prose 27 (October–November 1911): 122–129

- Du "Cubisme", written with Albert Gleizes, Edition Figuière, Paris, 1912 (First English edition: Cubism, Unwin, London, 1913)

- Art et esthétique, Lettres Parisiennes, le Salon des Indépendants, suppl. au n.9 (April 1920): 6–7

- Réponse à notre enquête – Où va la peinture moderne?, written with Fernand Léger, Bulletin de l'Effort moderne, February 1924, 5–6

- Bulletin de l'Effort moderne, June 1924, No. 6

- L'Evolution du coloris, Bulletin de l'Effort moderne, Paris, 1925

- Enquête du bulletin, Bulletin de l'Effort moderne, October 1925, 14–15

- Metzinger, Chabaud, Chagall, Gruber et André Mouchard répondent à l'enquête des Beaux-Arts sur le métric, Beaux-Arts, 2 October 1936, 1

- Un souper chez G. Apollinaire, Apollinaire, Paris, 1946

- Ecluses, 27 poems by Jean Metzinger, Preface by Henri Charpentier, Paris: G.L. Arlaud, 1947

- 1912–1946, Afterword to reprint of Du "Cubisme" by A. Gleizes and J. Metzinger, pp. 75–79, Paris, Compagnie française des Arts Graphiques, 1947

- Le Cubisme apporta à Gleizes le moyen d'écrire l'espace, Arts spectacles, no. 418, 3–9, July 1953

- Structures de peinture, Structure de l'esprit, Hommage à Albert Gleizes, with essays, statements and fragments of works by Gleizes, Metzinger, André Beaudin, Gino Severini, et al., Lyons, Atelier de la Rose, 1954

- Suzanne Phocas, Paris, Galerie de l'Institut, February 1955

- Le Cubisme était né, Souvenirs, Chambéry, Editions Présence, 1972

Museum collections

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, US

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US

- Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Massachusetts, US

- Centre Pompidou – Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, France (archived)

- Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, US

- Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy (archived)

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, US

- Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas, US

- National Galleries Scotland

- Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- National Gallery of Victoria, Victoria, Australia

- Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, US (archived)

- Tate Gallery, London, UK

- University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, Iowa, US

- Art Museum of West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia, US

References

- ↑ André Salmon, La Jeune Peinture française, Histoire anecdotique du cubisme, (Anecdotal History of Cubism), Paris, Albert Messein, 1912, Collection des Trente

- ↑ Salmon, André (1968). Anecdotal History of Cubism. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520014503., quoted in Chipp, Herschel Browning; et al. (1968). Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics. University of California Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-520-01450-2.

- ↑ Salmon, André (2005). André Salmon on French Modern Art. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85658-2.

- ↑ Apollinaire, Guillaume (1913). The Cubist Painters. Translated by Peter F. Read (also accompanying commentary) (2004 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 9780520243545.

- 1 2 3 Jean Metzinger, October–November 1910, "Note sur la peinture" Pan: 60

- 1 2 Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, p. 22

- ↑ Green, Christopher (2009). "Late Cubism". MoMA.com. Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Abraham Pais, Niels Bohr's Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity, Clarendon Press, 1991, p. 335, ISBN 0198520492

- ↑ Miller, A., 2002, Einstein, Picasso: space, time and the beauty that causes havoc, Basic Books, New York, 2001, pp. 166–169, 256–258

- ↑ "Royal Ancestry file, Jean Metzinger family members". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26.

- ↑ Leonore, culture.gouv.fr database, Nicolas Metzinger

- ↑ "Page:Notices sur les rues de Nantes 1906.djvu/217 - Wikisource". fr.wikisource.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jean Metzinger, 1883–1956: exposition, Nantes, École des beaux-arts, Atelier sur l'herbe, 4 au 26 janvier 1985

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Le Cubisme était né, Souvenirs, Chambéry, Editions Présence, 1972

- ↑ Salon d'automne; Société du Salon d'automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Petit Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1903

- ↑ Le Morvan, Marianne (2011). Berthe Weill: 1865–1951 – La petite galeriste des grands artistes. L'Ecarlate. ISBN 978-2-296-56097-0.

- 1 2 Mendelsohn, Ezra (18 May 1994). "Should We Take Notice of Berthe Weill? Reflections on the Domain of Jewish History". Jewish Social Studies. 1 (1): 22–39. JSTOR 4467433.

- ↑ Salon d'automne; Société du Salon d'automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1904

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Robbins, Daniel (1985). Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism. Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press. pp. 9–23.

- ↑ Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, Jean Metzinger, Bañistas (Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape)

- ↑ Baronesa Carmen Thyssen, Bañistas: dos desnudos en un paisaje exótico (Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape), 1905–06, by Jean Metzinger, exhibited in Gauguin y el viaje a lo exótico, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, 9 October 2012 – 13 January 2013

- ↑ "Société des artistes indépendants : catalogue de la 21ème exposition, 1905". libmma.contentdm.oclc.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.

- 1 2 3 Clement, Russell T. (1994). Les Fauves: A sourcebook – via archive.org.

- ↑ "Société des artistes indépendants : catalogue de la 22ème exposition, 1906". libmma.contentdm.oclc.org. Rare Books in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.

- ↑ Salon d'automne; Société du Salon d'automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1907

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, La Poésie symboliste. L'Après-midi des poètes: la Phalange nouvelle, p. 131-242, Paris, 1908

- ↑ Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris 1937, L'Art Indépendant, ex. cat. ISBN 2-85346-044-4, Paris-Musées, 1987, p. 188

- ↑ Mittelmann, Alex (2012). "Jean Metzinger, Divisionism, Cubism, Neoclassicism and Post Cubism". Alex Mittelmann.

- ↑ "History of Art: Jean Metzinger". all-art.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herbert, Robert (1968). Neo-Impressionism. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

- ↑ Salon d'automne; Société du Salon d'automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1906, Robert Delaunay, Portrait de M. Jean Metzinger, no. 420; Jean Metzinger, Portrait de M. Robert D..., no. 1191

- ↑ "Vente de biens allemands ayant fait l'objet d'une mesure de Séquestre de Guerre: Collection Uhde. Paris". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries. 30 May 1921.

- ↑ Jean Metzinger. Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo.

- ↑ "Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo". Archived from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, circa 1907, quoted by Georges Desvallières in La Grande Revue, vol. 124, 1907

- ↑ Louis Chassevent: Les Artistes indépendants, 1906, quoted in Daniel Robbins, preface to the catalogue Albert Gleizes, Paris (MNAM) 1964–65, p.20

- 1 2 3 Burgess, Gelett (May 1910). "The Wild Men of Paris". The Architectural Record.

- 1 2 Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Pre-Cubist works, 1904–1909, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press 1985, pp. 34–42

- ↑ Bovy, Adrien (27 March 1909). La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité : supplément à la Gazette des beaux-arts, La Chronique des Arts, Petites Expositions, Union central des Arts décoratifs. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. p. 102.

- ↑ Vauxcelles, Louis (18 March 1910). A travers les salons: promenades aux Indépendants. Gil Blas.

- ↑ "Albert Gleizes, Chronology of his life 1881-1953". peterbrooke.org.uk.

- ↑ "Salon d'Automne". Kubisme.info. 1911.