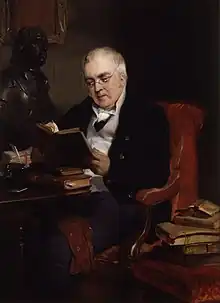

John Allen (3 February 1771 – 10 April 1843) was a prominent eighteenth and nineteenth century political and historical writer, and Master of the College of God's Gift in Dulwich (then colloquially called "Dulwich College").[1] More than one street in Kensington, London, is named after him.[2]

Early life

John Allen was born at Redfoord in the parish of Colinton near Edinburgh. His father, James Allen, was the owner of the small estate of Redfoord and was a writer to the Signet. When his father became bankrupt his mother's family and his stepfather ensured that he had a good education. In time he was apprenticed to an Edinburgh surgeon by the name of Arnot. Whilst there his companion in instruction was Professor Thomson who would be a lifelong friend.[1]

Early career

In 1791 he became M.D. of the University of Edinburgh. After achieving his M.D. he waited for a practice in Edinburgh and whilst doing so lectured on medical topics with students including Francis Horner being attracted. He also translated Cuvier's "Introduction to the Study of the Animal Economy".[1]

He was also known for his promotion of the cause of political reform in Scotland and had a deep knowledge of constitutional history.[1] This led to him being one of the few to whom a plan of the Edinburgh Review was communicated.

Association with Lord Holland

Trips abroad

In 1801 it became known that Lord Holland required the services of a clever young Scotch medical man to accompany him to Spain. Allen was recommended[3] John Allen took up the position and accompanied Holland's family remaining abroad until 1805. When he returned he spent much of his time at Holland House in Kensington. For a brief time in 1806 he held an official position as undersecretary to the commissioners for treating with America. In 1808 he again accompanied Lord Holland to Spain and made a study of the history and social characteristics of the Spanish people. His work towards a volume illustrating the different causes that had checked Spain's progress was never finished. However, in April 1810 two articles were published in the Edinburgh Review on Spanish America.[1]

Holland House

During the tenure of Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840) (son of the 2nd Baron) and his wife Elizabeth Vassall (1771-1845), John Allen's association with Holland House is perhaps what he is best known for, hence he is often referred to as Holland House Allen. In histories of Holland House he is frequently referred to as "Lord Holland's librarian".

Allen became one of the family, was in all their confidence, and indispensable to both Lord and Lady Holland. Following Allen's death, his associate in the "Holland House Set" Charles Greville wrote:[4]

- Lord Holland treated him with uniform consideration, affection, and amenity; [Lady Holland] worried, bullied, flattered, and cajoled him by turns. He was a mixture of pride, humility, and independence; he was disinterested, warm-hearted, and choleric, very liberal in his political, still more in his religious opinions, in fact, a universal sceptic. He used for a long time in derision to be called "Lady Holland's Atheist", and in point of fact I do not know whether he believed in the existence of a First Cause, or whether, like Dupuis, he regarded the world as l'univers Dieu. Though not, I think, feeling quite certain on the point, he was inclined to believe that the history of Jesus Christ was altogether fabulous or mythical, and that no such man had ever existed. He told me he could not get over the total silence of Josephus as to the existence and history of Christ. ... Allen's learning and still more his general information were prodigious, and as he lived amongst books, the stock was continually increasing. He was the oracle of Holland House on all literary subjects, and in every discussion some reference was sure to be made to Allen for information, upon which he never was at fault. He was not accustomed to take much part in general conversation, but was always ready to converse with anybody who sought him, and when warmed up would often argue away with great vigour and animation, and sometimes with no little excitement.

He spent much time helping Lord Holland find materials for his speeches in the House of Lords and supplying criticism of those speeches. He sat at the dinner table and carved. He was known to join the family at dinner parties. So associated was he with the house that he had his own large room, on the ground floor, known as "Allen's Room".

During his time at Holland House he came into contact with many of the most prominent citizens of London at the time. Byron referred to him as "the best informed and one of the ablest men" that he knew. Others, such as Macaulay, Lord Brougham and Charles Greville are laudatory of him.[1]

College of God's Gift

In 1811, through the influence of his patron Lord Holland,[5] he was elected as Warden of the College of God's Gift and from 1820 was the Master of that establishment until his death in 1843.[6] He is not considered one of the great Masters of the College as he spent little time there and did little to further the aims of its founder Edward Alleyn. However, he did leave his Spanish and Italian books to the school.

Later life

Apart from the Mastership of the College of God's Gift, he was also auditor of the Duchy of Lancaster from 1841 until his death. He died on 10 April 1843 at 33 South Street (the residence of Lady Holland) and was buried at Millbrook, Bedfordshire close to the third Lord Holland. His great friend Professor Thomson received his medical books and manuscripts, and Major-General Charles Richard Fox was left his other manuscripts and diaries.[1]

Publications

It is believed that, had he not spent so much time at Holland House, his contributions to literature would have been more prolific.[1]

- Articles for the Edinburgh Review including:

- Constitution of Parliament (June 1816)

- Review of Warden's letters from St. Helena (December 1816) – Napoleon was said to have been surprised by its intimate knowledge of his early life

- Criticisms of John Lingard's History of England (April 1825 and June 1826)

- Dissertation on creating peers for life (October 1834)

- Enquiry into the Rise and Growth of the Royal Prerogative in England (1830)

- Vindication of the Ancient Independence of Scotland

The Memorials and Correspondence of Charles James Fox had large portions written by Allen, although Lord John Russell is considered the editor. The life of Fox in the 7th and 8th editions of Encyclopædia Britannica were written by Allen who was steeped in the history of the Whigs.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Brian Harrison (ed), (2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, pages 309–310, (Oxford University Press)

- ↑ Liechtenstein, Princess Marie, Holland House, Vol.1, London, 1874, p.267

- ↑ Reports differ as to who made the recommendation. It was one of either Lord Lauderdale or Sydney Smith.

- ↑ |Charles Greville|The Greville MemoirsGreville, Charles (1885). "XV". The Greville Memoirs (second part); a journal of the reign of Queen Victoria, from 1837 to 1852. Vol. 5. London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 157–8. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ Walker, Annabel & Jackson, Peter, Kensington & Chelsea: A Social and Architectural History, London, 1987, p.25

- ↑ Ormiston, T. L., (1926), Dulwich College Register, page 9, (J J Keliher & Co Ltd: London)