Johor Sultanate کسلطانن جوهر Kesultanan Johor | |

|---|---|

| 1528—1855 1886—1942 1942—1945 (Japanese occupation) 1945—1946 1948—present | |

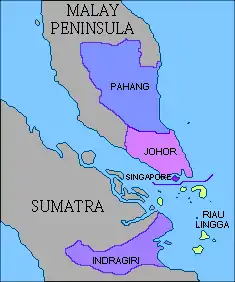

Map showing the partition of the Johor Empire before and after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, with the post-partition Johor Sultanate shown in the brightest purple, at the tip of the Malay Peninsula[2] | |

| Status | Rump state of the Malaccan Sultanate |

| Capital |

|

| Common languages | Malay |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Government | Absolute Monarchy |

| Sultan | |

• 1528–1564 | Alauddin Riayat Shah II (first) |

• 1812–1830 | Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah (last official sultan) |

• 1819–1835 | Hussein Shah (puppet monarch) |

• 1835–1855 | Ali Iskandar Shah (last sultan of Johor Sultanate) |

| Bendahara | |

• 1513–1520 | Tun Khoja Ahmad (first) |

• 1806–1857 | Tun Ali (last) |

| Currency | Tin ingot, native gold and silver coins |

| Today part of | Malaysia Singapore Indonesia |

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Johor Sultanate (Malay: Kesultanan Johor or کسلطانن جوهر; also called the Sultanate of Johor, Johor-Pahang-Riau-Lingga, or the Johor Empire) was founded by Malaccan Sultan Mahmud Shah's son, Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah II in 1528. Prior to being a sultanate of its own right, Johor had been part of the Malaccan Sultanate before the Portuguese conquered its capital in 1511. At its height, the sultanate controlled areas in what is now modern-day Johor, Pahang, Terengganu, territories stretching from the rivers of Klang to the Linggi and Tanjung Tuan, respectively situated in the states of Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Malacca (as an exclave), Singapore, Pulau Tinggi and other islands off the east coast of the Malay peninsula, the Karimun islands, the islands of Bintan, Bulang, Lingga and Bunguran, and Bengkalis, Kampar and Siak in Sumatra.[3] During the colonial era, the mainland part was administered by the British, and the insular part by the Dutch, thus breaking up the sultanate into Johor and Riau. In 1946, the British section became part of the Malayan Union. Two years later, it joined the Federation of Malaya and subsequently, the Federation of Malaysia in 1963. In 1949, the Dutch section became part of Indonesia.

History

Fall of Malacca and the rise of Johor

In 1511, Malacca fell to the Portuguese and Sultan Mahmud Shah was forced to flee Malacca. The sultan made several attempts to retake the capital but his efforts were fruitless. The Portuguese retaliated and forced the sultan to flee to Pahang. Later, the sultan sailed to Bintan and established a new capital there. With a base established, the sultan rallied the disarrayed Malay forces and organised several attacks and blockades against the Portuguese position.

Based at Pekan Tua, Sungai Telur, Johor, the Johor Sultanate was founded by Raja Ali Ibni Sultan Mahmud Melaka, known as Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah II (1528–1564), in 1528.[4] Although Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah and his successor had to contend with attacks by the Portuguese in Malacca and by the Acehnese in Sumatra, they managed to maintain their hold on the Johor Sultanate.

Frequent raids on Malacca caused the Portuguese severe hardship and it helped to convince the Portuguese to destroy the exiled sultan's forces. A number of attempts were made to suppress the Malay but it was not until 1526 that the Portuguese finally razed Bintan to the ground. The sultan then retreated to Kampar in Sumatra and died two years later. He left behind two sons named Muzaffar Shah and Alauddin Riayat Shah II.[4]

Muzaffar Shah continued on to establish Perak while Alauddin Riayat Shah became the first sultan of Johor.[4]

Triangular war

The new sultan established a new capital by the Johor River and, from there, continued to harass the Portuguese in the north. He consistently worked together with his brother in Perak and the Sultan of Pahang to retake Malacca, which by this time was protected by the fort A Famosa.

On the northern part of Sumatra around the same period, Aceh Sultanate was beginning to gain substantial influence over the Straits of Malacca. With the fall of Malacca to Christian hands, Muslim traders often skipped Malacca in favour of Aceh or also of Johor's capital Johor Lama (Kota Batu). Therefore, Malacca and Aceh became direct competitors.

With the Portuguese and Johor frequently locking horns, Aceh launched multiple raids against both sides to tighten its grip over the straits. The rise and expansion of Aceh encouraged the Portuguese and Johor to sign a truce and divert their attention to Aceh. The truce, however, was short-lived and with Aceh severely weakened, Johor and the Portuguese had each other in their sights again. During the rule of Sultan Iskandar Muda, Aceh attacked Johor in 1613 and again in 1615.[5]

Dutch Malacca

In the early 17th century, the Dutch reached Southeast Asia. At that time the Dutch were at war with the Portuguese and allied themselves to Johor. Two treaties were signed by Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge on behalf of the Dutch Estates General and Raja Bongsu (Raja Seberang) of Johor in May and September 1606.[6] Finally in 1641, the Dutch and Johor forces headed by Bendahara Skudai, defeated the Portuguese. As per the agreement with Johor struck in May 1606, the Dutch took control of Malacca and agreed not to seek territories or wage war with Johor. Finally in January 1641, the Dutch (attacking by land and the sea) and Johor forces (attacking by land and under the leadership of Bendahara Skudai), defeated the Portuguese at Malacca. By the time the fortress at Malacca surrendered, the town's population had already been greatly decimated by famine and disease (the plague).[7] As per article 1 of the agreement with Johor ratified in May 1606, the Dutch assumed control of the town of Malacca and also of some surrounding settlements. Malacca then became a territory under the control of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and formally remained a Dutch possession until the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 was signed.

Johor-Jambi war

With the fall of Portuguese Malacca in 1641 and the decline of Aceh due to the growing power of the Dutch, Johor started to re-establish itself as a power along the Straits of Malacca during the reign of Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah III (1623–1677).[8] Its influence extended to Pahang, Sungei Ujong, Malacca, Klang and the Riau Archipelago.[9] During the triangular war, Jambi also emerged as a regional economic and political power in Sumatra. Initially there was an attempt of an alliance between Johor and Jambi with a promised marriage between the heir Raja Muda and daughter of the Pengeran of Jambi. However, the Raja Muda married instead the daughter of the Laksamana Abdul Jamil who, concerned about the dilution of power from such an alliance, offered his own daughter for marriage instead.[10] The alliance therefore broke down, and a 13-year war then ensued between Johor and the Sumatran state beginning in 1666. The war was disastrous for Johor as Johor's capital, Batu Sawar, was sacked by Jambi in 1673. The Sultan escaped to Pahang and died four years later. His successor, Sultan Ibrahim (1677–1685), then engaged the help of the Bugis in the fight to defeat Jambi.[9] Johor would eventually prevail in 1679, but also ended in a weakened position as the Bugis refused to go home, and the Minangkabaus of Sumatra also started to assert their influence.[10]

After the sacking of Batu Sawar in 1673, the capital of Johor was frequently moved to avoid the threat of attack from Jambi. All through its history, the rulers of Johor had in fact constantly shifted their centre of power many times in their efforts to keep the sultanate together. Johor Lama (Kota Batu) was initially founded by Alauddin Riayat Shah II but was sacked by the Acehnese in 1564. It was then moved to Seluyut, later back to Johor Lama during the reign of Ali Jalla (1571–1597) which was sacked by the Portuguese in 1587, then to Batu Sawar, and Lingga (again sacked by the Portuguese). This is followed by a period with no fixed capital (places included Tanah Puteh and Makam Tauhid) during the reign of Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah III before he moved it to Batu Sawar in 1640. After Batu Sawar was sacked by Jambi, later capitals included Kota Tinggi, Riau, and Pancur.[11]

Golden Age

In the 17th century with Malacca ceasing to be an important port, Johor became the dominant regional power. The policy of the Dutch in Malacca drove traders to Riau, a port controlled by Johor. The trade there far surpassed that of Malacca. The VOC was unhappy with that but continued to maintain the alliance because the stability of Johor was important to trade in the region.

The Sultan provided all the facility required by the traders. Under the patronage of the Johor elites, traders were protected and prospered.[12] With a wide range of goods available and favourable prices, Riau boomed. Ships from various places such as Cambodia, Siam, Vietnam and all over the Malay Archipelago came to trade. The Bugis ships made Riau the centre for spices. Items found in China or example, cloth and opium were traded with locally sourced ocean and forest products, tin, pepper and locally grown gambier. Duties were low, and cargoes could be discharged or stored easily. Traders found they do not need to extend credit, for the business was good.[13]

Like Malacca before it, Riau was also the centre of Islamic studies and teaching. Many orthodox scholars from the Muslim heartlands like the Indian Subcontinent and Arabia were housed in special religious hostels, while devotees of Sufism could seek initiation into one of the many Tariqah (Sufi Brotherhood) which flourished in Riau.[14] In many ways, Riau managed to recapture some of the old Malacca glory. Both became prosperous due to trade but there was a major difference; Malacca was also great due to its territorial conquest.

Bugis and Minangkabau influence

The last sultan from the Malaccan dynasty, Sultan Mahmud Shah II, was a person of unstable disposition. When Bendahara Habib was the Bendahara, he effectively shielded the people from the Sultan 's idiosyncrasies. After the demise of Bendehara Habib, he was replaced by Bendahara Abdul Jalil. As the Bendahara was only a cousin, he could not rein in the Sultan 's eccentric behaviour.

The Sultan ordered the pregnant wife of a noble, Orang Kaya Megat Sri Rama killed, as she had taken a slice of the royal jack fruit. Subsequently, the Sultan was killed by Megat Sri Rama in revenge. Sultan Mahmud Shah II of Johor had died in 1699 without an heir. The Orang Kayas, who were normally tasked with advising the Sultan, were in a fix. They went to Muar to meet Sa Akar DiRaja, Raja Temenggong of Muar, the Sultan's uncle and asked for his counsel. He pointed out that Bendahara Abdul Jalil should inherit the throne.[15] The problem was resolved when the viceroy Bendahara Abdul Jalil was declared the new sultan and proclaimed Sultan Abdul Jalil IV. Many, particularly the Orang Laut (islanders from Johor maritime territories), however felt that the declaration was improper.

The Bugis, who played an important role in defeating Jambi two decades earlier, had a huge influence in Johor. Apart from the Malays, another influential faction in Johor at that time were the Minangkabau. Both the Bugis and the Minangkabau realised how the death of Sultan Mahmud II had provided them with the chance to exert power in Johor. The Minangkabau introduced a Minangkabau prince, Raja Kecil from Siak who claimed he was the posthumous son of Sultan Mahmud II. The prince met with the Bugis and promised the Bugis wealth and political power if they helped the prince to win the throne. However, Raja Kecil broke his promise and installed himself as the new Sultan of Johor (Sultan Abdul Jalil Rahmat Shah) without the knowledge of the Bugis. Sultan Abdul Jalil IV fled to Pahang where he was later killed by an assassin hired by Raja Kecil.

Dissatisfied with Raja Kecil's accession, the son of Sultan Abdul Jalil IV, Raja Sulaiman, asked Daeng Parani of the Bugis to aid him in his quest to reclaim the throne. In 1722, Raja Kecil was dethroned by Raja Sulaiman's supporters with the assistance of the Bugis. Raja Sulaiman became the new Sultan of Johore, but he was a weak ruler and became a puppet of the Bugis. Daeng Parani's brother, Daeng Merewah, who was made Yam Tuan Muda (crown prince) was the man who actually controlled Johor.[16]

Throughout the latter reign of Sultan Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah in the mid-18th century, real power was held in the hands of the Bugis. By 1760, several Bugis lineages had intermarried into the royal Johor family and gained great power. These Bugis lineages held the office of Yamtuan Muda, passing the office back and forth between themselves. The death of Sultan Sulaiman triggered a succession dispute, which was lost by the combined Bendahara-Temenggong court elite to the Bugis faction.[17] From 1760 to 1784, the latter group completely dominated the sultanate. The Johor economy was reanimated under Bugis rule, along with the introduction of Chinese traders. However, by the late 18th century, Engkau Muda of the Temenggong faction under Sultan Mahmud Shah III gained power at the expense of the Bugis.[18] Engkau Muda's son, Temenggong Abdul Rahman and his descendants would soon be responsible for the growth in prospects for the sultanate.

The British arrival

Singapore and the British

In 1818, Sir Stamford Raffles was appointed as the governor of Bencoolen on western Sumatra. However, he was convinced that the British needed to establish a new base in Southeast Asia to compete with the Dutch. Though many in the British East India Company opposed such an idea, Raffles managed to convince Lord Hastings of the company, then governor general of British India, to side with him. With the governor general's consent, he and his expedition set out to search for a new base.

When Raffles' expedition arrived in Singapore on 29 January 1819 he discovered a small Malay settlement at the mouth of the Singapore River headed by a Temenggong Abdul Rahman, son of Engkau Muda. Though the island was nominally ruled by the sultanate, the political situation there was extremely murky. The reigning sultan, Tengku Abdul Rahman, was under the influence of the Dutch and the Bugis. Hence, he would never agree to a British base in Singapore.

However, Tengku Abdul Rahman was ruler only because his older brother, Tengku Hussein or Tengku Long, had been away in Pahang getting married when their father died in 1812. He was appointed by the Yam Tuan Muda of Riau, Raja Jaafar because according to him, in a Malay tradition, a person has to be by the dying sultan's side to be considered as the new ruler. However the matter has to be decided by the Bendehara as the "keeper of adat (tradition)".[19] Predictably, the older brother was not happy with the development.

Raja Jaafar's sister, the queen of the late Sultan, protested vehemently at her brother's actions with these prophetic words, "... Which adat of succession is being followed? Unfair deeds like this will cause the Johor Sultanate be destroyed!". And she held on the royal regalia refusing to surrender it.[20]

Bendehara Ali was made aware of the affairs of the succession and decided to act.[19] He prepared his fleet of boats to Riau to "restore the adat". The British upon knowing this despatched a fleet and set up a blockade to stop the forces of Bendehara Ali from advancing.

With Temenggong Abdul Rahman's help, Raffles managed to smuggle Hussein, then living in exile on one of the Riau Islands, back into Singapore. According to a correspondence between Tengku Hussain and his brother, he left for Singapore out of his concern of his son's safety. Unfortunately he was captured by Raffles and forced to make a deal.[21] Their agreement stated that the British would acknowledge Tengku Hussein as the "legitimate ruler" of "Johor", and thus Tengku Hussein and the Temenggong would receive a yearly stipend from the British. In return, Tengku Hussein would allow Raffles to establish a trading post in Singapore. This treaty was ratified on 6 February 1819.

Bendehara Ali was requested by the British to recognise Tengku Hussein as a ruler. However, Bendehara Ali claimed that he had no connection with the events in Singapore, as it is the Temenggong's fief and stated that his loyalty lies only with the Sultan of Johor in Lingga.[22]

Anglo-Dutch Treaty

The Dutch were extremely displeased with Raffles' action. Tensions between the Dutch and British over Singapore persisted until 1824, when they signed the Anglo-Dutch Treaty. Under the terms of that treaty, the Dutch officially withdrew their opposition to the British presence in Singapore. Many historians contend that the treaty divided the spheres of influence between the Dutch and the English; Sultanate of Johor into modern Johor and the state of Riau-Lingga which exists de jure after the ouster of the last sultan of Johor. However this treaty was signed secretly without the knowledge of the local nobility including the Sultan and thus its legitimacy was called into question.

Nevertheless, the British successfully sidelined Dutch political influence by proclaiming Sultan Hussein as the sultan of Johor and Singapore to acquire legal recognition in their sphere of influence in Singapore and Peninsular Malaysia. The legitimacy of Sultan Hussein's proclamation as the sultan of Johor and Singapore was controversial to some of the other Malay rulers. As he was placed on the throne by the British, he was also very much seen as a puppet ruler. Temenggong Abdul Rahman's position, on the other hand, was strengthened as it was with his co-operation that the British successfully took de facto control of Johor and Singapore; with the backing of the British he gained influence as Raja Ja'afar.[23] Meanwhile, Sultan Abdul Rahman was installed as the sultan of Lingga in November 1822, complete with the royal regalia.[24] Sultan Abdul Rahman, who had devoted himself to religion, became contented with his political sphere of influence in Lingga, where his family continued to maintain his household under the administrative direction of Raja Ja'afar who ruled under the auspices of the Dutch.

The interested parties

The actors on this stage were three parties; the colonial powers of British and the Dutch; the nobles who made agreement with the Dutch namely Raja Jaafar, Yam Tuan Muda of Riau and Temenggong Abdul Rahman, of Johore and Singapore; the palace namely the sultan, and the bendahara who claimed he was not aware of any treaty signed with their knowledge.[25] Because the treaties were not ratified by the sultan or the bendahara, the Malays tried not to pay heed to any action of the colonial powers.

The Yam Tuan Muda has been accused of committing treachery by "selling" the sovereignty of Johore,[26] however the counter argument is that neither the sultan nor the bendahara were parties to the treaty. The treaty was signed in secret[27] and details were only known in 1855. The temenggong strengthened his position through his friendship with Great Britain, and gained influence, together with Britain, over the state at the expense of the sultanate. This is especially true for the son of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim, the ambitious Temenggong Abu Bakar succeeded in eventually usurping the throne.

Sultan tries to repair the damage

Sultan Abdul Rahman died in 1832 and was replaced by his son, Sultan Muhammad Shah (reigning from 1832 to 1841). Raja Jaffar, Yam Tuan Muda of Riau, died and the sultan was in no hurry to appoint a successor. The sultan saw the damage that was done to the palace in his father's reign and decided to reemphasis and restore adat[28] as a rule governing personal behaviour and the politics. He summoned Bendahara Ali (Raja Bendahara Pahang) to Lingga. At Lingga, an adat-steeped function[29] was held. The bendahara conducted ceremonies (as per adat) aimed at re-educating the nobility and the sultan about their respective duties and responsibilities. Islam and politics were discussed. It was attended by all the nobles from across the empire, hence, proving that the 'sultan' of Singapore was not recognised by the Malays. The ceremonies also included the installation of Tengku Mahmud (later ruling as Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar) as crown prince and Tun Mutahir as bendehara-in-waiting.

In 1841, Bendahara Ali appointed Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim[30] to replace his father, who died in 1825. The long interval was due to displeasure of the Bendahara over the affairs of Singapore. Conditions imposed during the appointment included paying a visit of fealty to the ruling Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar in Lingga. Sultan Hussein of Singapore died in 1835 and his prince Tengku Ali wished for the legitimacy granted to Temenggong Ibrahim, by the British and some Malay nobles. The British forwarded the request in 1841 to the Bendahara Ali.

After waiting since 1835 for the 'appointment' as sultan, in 1852 Tengku Ali decided to return Johor[31] to the former Johor-Riau Empire by paying homage to Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar in Lingga. For three years Johor Empire was one again, except Singapore which was ceded to the British. Worried by the state of affairs, the British called Tengku Ali back to Singapore on the threat of cancelling his pension. In Singapore, he was frequently visited by Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar, and their relationship was cordial.

End of the empire

The worried British then forced the 1855 treaty between Temenggong Ibrahim and Tengku Ali. In exchange for recognition as sultan, Tengku Ali agreed to 'give up all of Johor'. The treaty was intended to solidify the position of Temenggong Ibrahim, their key ally.

Bendahara Ali was asked by the Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar about the 1855 treaty.[32][33] In his reply, the bendahara reiterated that the temenggong was supposed to swear fealty to his majesty and on the behaviour of Tengku Ali, the bendehara claimed ignorance. He also reiterated that he was not a party to any discussion with the British or the Dutch.

The Dutch were also very worried. It seemed that the sultan was acting on his own and would not listen to any of the Dutch-influenced Yam Tuan Muda of Riau and the Bugis nobility. It erupted into an open dispute between Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar and the Bugis nobility over the appointment of new Yam Tuan Muda of Riau. The Bugis preferred candidate was also the Dutch choice.[34] The sultan resented having another foreign-backed Yam Tuan Muda of Riau. It resulted in a deadlock and the sultan set sail to Singapore to cool off. It was during the Singapore trip that the last Johor sultan was deposed by the Bugis nobility in 1857.[35]

The breakup

After the ouster of the former sultan of Johor-Riau, the Bugis nobles elected the new sultan, Sulaiman Badrul Shah,[36] the sultan of the "new" Riau-Lingga Kingdom built on the Riau remnants of the Johore Empire. The sultan signed an agreement with the Dutch.[36] In the agreement he agreed to acknowledge the overlordship of the Dutch government among others. With a stroke of a pen, he broke up the Johor Empire into two big parts and gave up the sovereignty of his part of territory to the Dutch. This also marked the end of the original Johor-Riau Sultanate, that descended from the Sultanate of Melaka. This division remains until today as the Malaysia–Indonesia border.

Johor and Pahang

Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim of Johore signed a treaty with Bendahara Tun Mutahir of Pahang in 1861.[37] The treaty recognised the territories of Johor (mainland), the temenggong and his descendants' right to rule it, mutual protection and mutual recognitions of Pahang and Johor. With the signing of this treaty, the remnants of the empire became two independent states, Johor and Pahang.

Modern period

State of Johor Negeri Johor نڬري جوهر | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1886–1942 1945–1946 1948—present | |||||||||

| Motto: Malay: Kepada Allah Berserah (To Allah We Surrender) | |||||||||

Johor in present-day Malaysia | |||||||||

| Status | Independent sultanate (1886–1914) Protectorate of the United Kingdom (1914–1942, 1945–1946) | ||||||||

| Capital | Johor Bahru1 | ||||||||

| Common languages | Malay2 English | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1886–1895 | Abu Bakar | ||||||||

• 1895–1959 | Ibrahim | ||||||||

| Advisor | |||||||||

• 1914–1918 | Douglas G. Campbell | ||||||||

• 1935–1939 | W. E. Pepys | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Recognised by United Kingdom | 11 December 1885 | ||||||||

• British adviser accepted | 12 May 1914 | ||||||||

• Japanese troops take Johor Bahru | 31 January 1942 | ||||||||

| 14 August 1945 | |||||||||

• Added into Malayan Union | 31 March 1946 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1931 | 505,311[38] | ||||||||

| Currency | Straits dollar until 1939 Malayan dollar until 1953 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Malaysia | ||||||||

1 Formerly Tanjung Puteri, remains as capital until today 2 Malay using Jawi (Arabic) script | |||||||||

In 1855, Temenggong Ibrahim selected Tanjung Puteri, a small fishing village in southern Johor which would later develop into Johor Bahru, as the administrative headquarters of the state. Temenggong Ibrahim was succeeded by his son, Temenggong Abu Bakar, who later took the title Seri Maharaja Johor.

Muar was another vassal of the old Johor empire and was ruled by its own Raja Temenggong. At gunpoint, the Raja Temenggong and the chieftains of Muar handed over the control of Muar to Temenggong Abu Bakar in 1877; this later contributed to the Jementah Civil War. Temenggong Abu Bakar, aided by the British won decisively. Abu Bakar went to Istanbul to seek recognition as the sultan of Johor, to allay fears of his religious credibility.

In 1885, he went to London seeking the recognition from the British Queen, Queen Victoria on his sultanate and Johor's independence. He was warmly accepted by the Queen and a friendship treaty was signed. After that he was formally crowned the Sultan of Johor. The modern Sultanate of Johor ruled only over mainland Johor. The old Johore sultanate (Johore Empire) was thus broken up into its constituents: Pahang, Singapore, Lingga/Riau and mainland Johor.

Sultan Abu Bakar has often been credited as the "Father of Modern Johor" due to the modernisation of the state under his rule. He introduced a constitution known as Undang-undang Tubuh Negeri Johor and developed an efficient administration system, officially moving administrative operation of the state to Johor Bahru. As the capital of the state, Johor Bahru witnessed significant growth and development, culminating to the construction of buildings on grand scales with architecture deriving from Western and Malay sources. Johor as a whole also enjoyed economic prosperity. An increased demand for black pepper and gambier in the 19th century led to the opening up of farmlands to the influx of Chinese immigrants, creating Johor's initial economic base. The Kangchu system was put in place.

In 1914, Sultan Ibrahim, Sultan Abu Bakar's successor, was forced to accept a British adviser and effectively became a crown protectorate of the Britain as part of the Unfederated Malay States. D.G. Campbell was dispatched as the first British advisor to Johor.

World War II and Malaysia

Under the reign of Sultan Ibrahim until his death in London in 1959, Johor transitioned from a British protectorate of the Unfederated Malay States, to a Japanese possession during Japanese occupation in World War II, to a federated state in the Malayan Union and Federation of Malaya.

The Johor Sultanate continues to exist as a member of the Conference of Rulers following Malaya's independence in 1957 and the formation of the Malaysian federation in 1963, with successive sultans presiding over modern Johor as ceremonious figureheads, including Sultan Ismail (1959–1981), Sultan Iskandar (1981–2010), and Sultan Ibrahim (2010–present). Sultan Iskandar served as the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, the federal head of state of Malaysia, from 1984 to 1989.

Johor administration

The Johor Sultanate continued the system of administration previously practised in Malacca. The highest authority lay in the hands of the Yang di-Pertuan who was known as the Sultan. The Sultan was assisted by a body known as the Majlis Orang Kaya (Council of Rich Men) which was tasked with advising the Sultan. Among them were the Bendahara, Temenggong, Laksamana, Shahbandar and Seri Bija Diraja. During the 18th century, the Bendahara lived in Pahang and the Temenggong Johor in Teluk Belanga, Singapore. Each one managed the administration of their individual areas based on the level of authority bestowed upon them by the Sultan of Johor.

The Johor Empire was decentralised. It was made of four main fiefs and the Sultan's territory. The fiefs are Muar and its territories under the Raja Temenggong of Muar;[39] Pahang under the stewardship of the Bendehara;[40] Riau under the control of YAM Tuan Muda and mainland Johor and Singapore under the Temenggong. The rest of the Empire were directly controlled by the Sultan. The Sultan resided in Lingga. All the Orang Kayas except Raja Temenggong Muar reported directly to the Sultan; Raja Temenggong Muar was a suzerain recognised by the Sultan.

| Sultans of Johor | Reign |

|---|---|

| Malacca-Johor dynasty | |

| Alauddin Riayat Shah II | 1528–1564 |

| Muzaffar Shah II | 1564–1570 |

| Abdul Jalil Shah I | 1570–1571 |

| Ali Jalla Abdul Jalil Shah II | 1571–1597 |

| Alauddin Riayat Shah III | 1597–1615 |

| Abdullah Ma'ayat Shah | 1615–1623 |

| Abdul Jalil Shah III | 1623–1677 |

| Ibrahim Shah | 1677–1685 |

| Mahmud Shah II | 1685–1699 |

| Bendahara dynasty | |

| Abdul Jalil IV (Bendahara Abdul Jalil) | 1699–1720 |

| Malacca-Johor dynasty (descent) | |

| Abdul Jalil Rahmat Shah (Raja Kecil) | 1718–1722 |

| Bendahara dynasty | |

| Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah | 1722–1760 |

| Abdul Jalil Muazzam Shah | 1760–1761 |

| Ahmad Riayat Shah | 1761–1761 |

| Mahmud Shah III | 1761–1812 |

| Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah | 1812–1819 |

| Hussein Shah (Tengku Long) | 1819–1835 |

| Ali | 1835–1877 |

| Temenggong dynasty | |

| Raja Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim | 1855–1862 |

| Abu Bakar | 1862–1895 |

| Ibrahim | 1895–1959 |

| Ismail | 1959–1981 |

| Mahmud Iskandar Al-Haj | 1981–2010 |

| Ibrahim Ismail | 2010–present |

Extent of the Empire

As the Sultanate replaced the Malacca Sultanate, it followed that the extent of its territorial area covered the southern Malay peninsula, parts of south-eastern Sumatra and the Riau Islands and its dependencies. This territory included the vassal states of Pahang, Muar, Johor mainland and Riau Islands. The administrative centre of the empire was at various times at Sayong Pinang, Kota Kara, Seluyut, Johor Lama, Batu Sawar and Kota Tinggi; all on mainland Johor and later at Riau and Lingga. It then shifted with the birth of Modern Johore Sultanate to Tanjung Puteri, known today as Johor Bahru.

See also

References

- Turner, Peter; Hugh Finlay (1996). Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-86442-393-1.

- ↑ Turner, Peter; Hugh Finlay (1996). Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-86442-393-1.

- ↑ Winstedt, R. O. (1992). A history of Johore, 1365–1895. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. p. 36. ISBN 983-99614-6-2.

- 1 2 3 Husain, Muzaffar; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (2011). Concise History of Islam (unabridged ed.). Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 310. ISBN 978-93-82573-47-0. OCLC 868069299.

- ↑ Borschberg (2010a)

- ↑ Borschberg (2011), pp. 215–223

- ↑ Borschberg (2010b), pp. 97–100

- ↑ M.C. Ricklefs; Bruce Lockhart; Albert Lau; Portia Reyes; Maitrii Aung-Thwin (19 November 2010). A New History of Southeast Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-137-01554-9.

- 1 2 Tan Ding Eing (1978). A Portrait of Malaysia and Singapore. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-580722-6.

- 1 2 Baker, Jim (15 July 2008). Crossroads: A Popular History of Malaysia and Singapore (updated 2nd ed.). Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-981-4516-02-0. OCLC 218933671.

- ↑ Miksic, John N. (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800. NUS Press. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-9971-69-574-3. OCLC 1091767694.

- ↑ E. M. Jacobs, Merchant in Asia, ISBN 90-5789-109-3, 2006, page 207

- ↑ Andaya & Andaya (2001), p. 101

- ↑ Andaya & Andaya (2001), p. 102

- ↑ The Family Tree of Raja Temenggung of Muar, traditional sources, Puan Wan Maimunah, 8th descendant of Sa Akar DiRaja

- ↑ "History", Embassy of Malaysia, Seoul Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Trocki, Carl A. (2007). Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784-1885. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-9971-69-376-3.

- ↑ Trocki, Carl A. (2007). Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784-1885. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 33, 39. ISBN 978-9971-69-376-3.

- 1 2 Othman (2003), p. 57

- ↑ Othman (2003), p. 136

- ↑ Othman (2003), p. 61

- ↑ Othman (2003), p. 62

- ↑ Ministry of Culture (Publicity Division), Singapore; Ministry of Communications and Information, Singapore., Singapore: A Ministry of Culture Publication, pg 24

- ↑ Trocki (1979), p. 108

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 90

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 46

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 40

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 67

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 68

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 70

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 75

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 221

- ↑ Baginda Omar's private correspondences, National Archives, Kuala Lumpur

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 85

- ↑ Othman (2007), p. 86

- 1 2 Othman (2007), p. 87

- ↑ Ahmad Fawzi Basri, Johor 1855–1917 : Pentadbiran dan Perkembangannya, Fajar Bakti, 1988, pages 33–34

- ↑ "Census population by state, Peninsular Malaysia, 1901–2010". Economic History Malaya. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Othman (2006), p. 239

- ↑ Othman (2003), p. 36

Bibliography

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (2001). A History of Malaysia. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2425-9.

- Borschberg, Peter (2010a). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th Century. ISBN 978-9971-69-464-7.

- Borschberg, Peter (2010b). "Ethnicity, language and culture in Melaka during the transition from Portuguese to Dutch rule". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 83 (2): 93–117.

- Borschberg, Peter (2011). Hugo Grotius, the Portuguese and Free Trade in the East Indies. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-467-8.

- (Tun) Suzana (Tun) Othman (2003). Institusi Bendahara, Permata Melayu yang Hilang. Pustaka BSM. ISBN 983-40566-6-4.

- (Tun) Suzana (Tun) Othman (2006). Ahlul-Bait (keluarga) Rasullulah SAW dan Kesultanan Melayu. Crescent Publications. ISBN 983-3020-12-7.

- (Tun) Suzana (Tun) Othman (2007). Perang Bendahara Pahang 1857–63. Karisma Publications. ISBN 978-983-195-282-5.

- Trocki, Carl A. (1979). Prince of Pirates: the Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-376-3.

Further reading

- Borschberg, Peter, "Three questions about maritime Singapore, 16th and 17th Centuries", Ler História, 72 (2018): 31-54. https://journals.openedition.org/lerhistoria/3234

- Borschberg, Peter, "The Seizure of the Santa Catarina Revisited: The Portuguese Empire in Asia, VOC Politics and the Origins of the Dutch-Johor Alliance (c. 1602–1616)", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 33.1 (2002): 31–62.

- Borschberg, Peter, ed. (2015). Jacques de Coutre's Singapore and Johor, 1595-c.1625. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-852-2. https://www.academia.edu/9672124

- Borschberg, Peter, ed. (2015). Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge. Security, Diplomacy and Commerce in 17th-Century Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-798-3. https://www.academia.edu/4302783

- Borschberg, Peter, ed. (2015). Admiral Matelieff's Singapore and Johor, 1606-1616. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. https://www.academia.edu/11868450

External links

- The Johor Empire at sabrizain.demon.co

- JOHOR (Sultanate) at uq.net.au