Julian Augustus Selby | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | February 6, 1833 near Charleston, S.C. |

| Died | April 12, 1907 (aged 74) |

| Occupation(s) | Printer, Publisher and Journalist |

| Known for | Founder of The Phoenix newspaper |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | Alice Elizabeth Peers |

| Children | 6 |

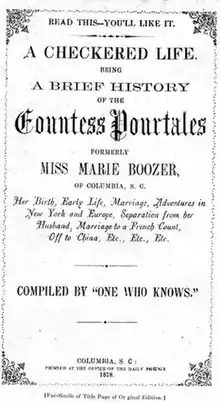

Julian Augustus Selby (February 6, 1833 – April 12, 1907) was a printer, publisher and journalist in Columbia, South Carolina. Aside from numerous newspaper articles, he wrote Memorabilia, a book of folksy reminiscences about the antebellum Columbia area. He also wrote an anonymous booklet called A Checkered Life (later reprinted as The Countess Pourtales) inveighing against a former resident of Columbia, Marie Boozer. Selby was remembered as "a man who created a high standard in journalism when newspapers were comparatively few in the South and the ashes of war and the sting of poverty made newspaper publishing a perilous financial undertaking."[1]

Life

Selby's mother Margaret was from the West Indies,[2] but Selby himself was born near Charleston[1] on February 6, 1833. Nothing is known about his father. His mother conducted a school in Columbia and Selby probably received his early education there.[3] The 1850 census shows him working as a printer at age 17.[2]

Selby was associated with the The South Carolinian for about twenty-one years, starting in August 1844.[4][5] The newspaper often featured literary material, sometimes from Selby's friends William Gilmore Simms and the poet Henry Timrod.

General Sherman's Union Army came to Columbia during the Carolinas Campaign. People expected Columbia to be well-defended by the Confederacy, but that hope was in vain.[6] "Timrod and Selby got out the last issue of The South Carolinian while Sherman’s shells were dropping nearby."[7] During the occupation from 17 to 20 February 1865, about a third of Columbia was destroyed by fires of various origin.[8] The newspaper printing equipment at The South Carolinian was mostly ruined during the Union occupation.

Selby decided to start a new newspaper. First he had to find a new press and related materials. Some printing supplies had been sent Upcountry in anticipation of Sherman's arrival. Selby and his party went to Dewberry; finding nothing there, they continued to Asheville, where they were able to buy newspaper type. In Greenville, they obtained paper and ink that they took back to Dewberry, where they purchased a mule team to get the material back to Columbia. At one point they had to display their weaponry (three Enfield rifles and several revolvers) to induce a ferryman to let them pass across a swollen river.[9]

A metal cylinder for a printing press was buried in the ruins of The South Carolinian office. Selby retrieved it and created a wood model for the bed of the press that workers could cast into metal form. They made rollers and improvise kettles of glue and molasses. A better press was available in Camden, so Selby set off with a mule team to buy it and bring it back to Columbia. On the way back, they again had to display their double-barreled guns to discourage unwanted visitors.[10]

On March 21, 1865, his new newspaper The Phoenix printed its first issue, rising like a Phoenix from the ashes of Columbia. "J.A. Selby" was the only name on the top of the first page. The Phoenix appeared in a daily, tri-weekly, and weekly edition, costing $5, $3.50, and $2 for a six-month subscription.[11] Economic conditions were so dire that his staff accepted "food staples such as bacon, eggs, rice, and potatoes as payment in lieu of cash subscriptions."[12]

The noted South Carolina author William Gilmore Simms was an editor for the paper. Simms wrote a series of articles for the first ten issues of The Phoenix detailing the suffering of Columbia during brief occupation by Sherman's army. These writings were re-edited into book form.[13]

In June 1865, Selby went to New York City with his wife and 6-year-old son Julian Peers to obtain printing materials. The South had surrendered on April 9, so this was quite soon after the end of the war. As a Southerner, Selby encountered some verbal hostility but had many positive encounters with the Northerners during the journey. The trip to New York took eight days by wagon, train, and steamboat. The trip back was made easier by taking a steamboat directly to Charleston.[14]

Selby had visited New York City several times over the years. Aside from the 1865 trip, he visited in 1852 for the first time,[15] in 1854 with his mother[16] and in 1859.[17] He knew the New York well since he mentions seeing the Metropolitan Museum,[18] Sing-Sing Prison,[19] Greenwood Cemetery[17] and the area later called the Tenderloin.[15] Selby's wife, Alice Elizabeth Peers, was born in New York.[20]

Around 1875, Selby sold The Daily Phoenix to a competing newspaper, The Columbia Daily Register.[12] The Phoenix ceased operation in 1878.

Selby wrote an anonymous booklet called A Checkered Life in 1878 criticizing Marie Boozer, a former resident of Columbia.

In the 1876 United States presidential election, the Hayes-Tilden contest was resolved by the Compromise of 1877. The Republican Hayes became president in exchange for an end to the Reconstruction era in the South. Selby recounted how this contest played out locally in South Carolina as a contest between the "Red Shirts" and the "Radicals". Selby supported the Red Shirts.[21]

In 1886, Selby decided to start a small newspaper in Charleston. The newspaper did well for five weeks until the 1886 Charleston earthquake struck. He was accompanied by his wife, daughter Margaret and son Gilbert and so had to attend to their safety too. Among Selby's many anecdotes about the quake, he said that the people of Charleston feared a tsunami like the one after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake. Instead the tides became stationary for four days.[22]

Selby later joined the R. L. Bryan Co., which was a large printing house in Columbia.[7][lower-alpha 1] Selby was still working there as a proofreader at the end of his life.[23]

When The State newspaper was founded in 1891 to oppose Governor Benjamin Tillman, the first press operation was run in the basement of the old city hall by Selby.[24]

Selby published his book Memorabilia in 1905.

After several weeks of heart problems, Selby passed away in Columbia on 12 April 1907. He was one of Columbia's oldest and best-known citizens.[1]

Memorabilia

Selby noted that he was "blessed by a retentative memory and disposed to inquire into matters and things generally".[25] These inclinations served him well when he wrote his 1905 book Memorabilia about life in Columbia and the surrounding Midlands.

In Memorabilia, Selby's recollection of his life was eclectic. He did not mention his education or his marriage. On the other hand, he gave a long report on a childhood trip to Charleston.[26] In the prologue he explained that the book was presenting events in an anecdotal salmagundi, like a large plated salad of many disparate ingredients.[27] He might report on the planting of trees[28] and then move on to some entirely unrelated criminal incident.

Selby recounted many odd occurrences over the years. As a child he witnessed three African Americans executed by hanging. One of the female enslaved servants at the boarding house took him there; the law allowed her to go anywhere at anytime if accompanied by a white child.[29] An attempted duel between two prominent officials was thwarted by the local sheriff.[30] Two white men were hanged in antebellum South Carolina for killing an African American.[31] Students at South Carolina College (later University of South Carolina) rioted in 1854 after the police arrested several of them. The students attempted to procure guns from their student "well-drilled and equipped military company",[32] but alert campus officials put the weapons out-of-reach. The law still provided for public whippings; "the lashes were never laid on hard", but "it had the effect of getting rid of bad characters."[33]

Selby was tolerant about religion. He mentioned the small Hebrew community in Columbia and particularly a Jewish convert to Christianity, Elias Marks. Marks' nephew, Frederick Humphrey Marks Jr, was one of the printers who helped Selby rebuild the presses after the Union Army passed through.[lower-alpha 2] Selby related a humorous story with the point that the verb "jew" should not be used for "seeking a better price."[34] There were positive recollections of a local Catholic priest.[35]

Selby had the skills of a good journalist who could quickly make friends with people and get them to talk freely with him. People wanted to do him favors. On his 1865 train trip North, he made friends with discharged "Yankee soldiers" and was given a train pass for ticket-free travel and sometimes free food and lodging.[36]

At the end of Memorabilia, Selby reprinted William Gilmore Simms's articles on the suffering in Columbia during the Union occupation.[37]

A Checkered Life

In 1878 Selby wrote and the Phoenix Press published an anonymous booklet called A Checkered Life. Selby wrote under the pseudonym "One Who Knows" to avoid the libel laws. The booklet was a sustained, gossipy, vituperative attack on the reputation of Marie Boozer and her mother Amelia Feaster and contained "many false tales".[38][lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4]

Selby reviewed Boozer's life to that point: her birth in South Carolina, her mother's four marriages, Boozer's life in Columbia during the Civil War, Boozer and Feaster's support of the Union, their flight North with Sherman's Army, Boozer's ascent into the New York elites, Boozer's marriage to John Beecher, her affair with Lloyd Phoenix, and her second marriage to the Count de Pourtales.[40] Although the facts were distorted, they still had some connection to the true story.

Then "the book completely sinks into the realm of fiction."[41] "Selby morphed an enchanting ocean passage into a salacious transatlantic sex romp with Marie, the captain, and a purser."[38][42] "Selby’s twisted narrative continued with Marie traveling to the American West in the company of other "fast women"."[43] The preposterous claim was that Boozer was abducted by Mormon women while passing through Salt Lake City, whipped until she agreed to polygamous marriage to an early LDS leader and his son, and rescued by U.S. Army troops alerted to her plight.[44]

Selby inserted a long highly-negative article from The San Francisco Chronicle.[45] The San Francisco Chronicle article was inspired by the wealthy businessman Ben Holladay, who was trying—ultimately unsuccessfully—to get custody of his granddaughter Maria de Pourtales from her stepmother Marie Boozer and the Count de Pourtales.[46] Lastly there was a letter, supposedly sent by Boozer from China.[45] When compared to authentic letters held by the family of Boozer's sister Ethland, it was obvious that the China letter was a forgery.[47]

Selby's booklet was reprinted in 1915 under the title The Countess Pourtales. In 1915, Selby's son Julian Peers Selby and his friend James Holmes[lower-alpha 5] wanted to make some Christmas money by reprinting A Checkered Life, but they felt that it needed padding to justify the price of $1. A University of South Carolina History Professor, the former journalist Yates Snowden, agreed to help.[48]

.jpg.webp)

Snowden wrote an introduction entitled A Study in Scarlett, signed only with the pseudonym "Felix Old Boy".[49] Like Selby, Snowden was not fastidious about his facts concerning Boozer.[lower-alpha 6] Snowden tells an untrue story of a romance between Major General Kilpatrick and Boozer.

The Countess Pourtales was published anonymously since young Selby, Holmes and Snowden still feared the libel laws.

Snowden unwisely sent a copy to his friend John Bennett,[52] who angrily wrote back that Snowden had "slandered the lovely Pourtales".[53] Bennett told Snowden that "... apropos of the fair personage you so vilely style “a Columbia strumpet,” the less you have to say on that subject, the better."[53]

Selby and Snowden may have been motivated by the belief that Boozer and her mother were disloyal to the South and that the women did not conform to the expected standards of "southern womanhood".[54][lower-alpha 7]

Observations on Slavery

The Columbia University historian Frederic Bancroft interviewed the elderly Selby in Washington, D.C. and in Columbia. Bancroft described Selby as a "quaint old printer" and found him to be "a mine of information, very chatty and entirely reliable."[56]

Bancroft quoted Selby on the extent of slave trading in Columbia, which was a town of only about 8000 people around 1860 but was the commercial hub for the Midlands of South Carolina.

There were four or five regular slave-jails in Columbia. ... Prospective buyers watched the advertisements and looked over the negroes in the jails. Columbia was the central point in this region from which the slaves were sent out. Certainly as many as 1,000 were taken from here in some years. Slaves were auctioned off as if they were cattle. Children were sometimes sold when not more than six or seven years of age.[57]

Selby reflected on the psychology of the townspeople toward slavery in a further quotation by Bancroft.

Slave-trading was not looked upon with favor, of course, but it was regarded as a necessary evil. So far as buying and selling were concerned, our people were perfectly callous. Slavery was considered necessary and must be defended whether moral or immoral. One would have run great risk in attempting to oppose it.[57][lower-alpha 8]

Notes

- ↑ Selby's son Gilbert was still working for R. L. Bryan Co. in 1948.[7]

- ↑ The printer Frederick Humphrey Marks Jr even named a son "Julian Augustus" after Selby.

- ↑ Selby never mentions Boozer or Feaster in Memorabilia.

- ↑ Selby said in A Checkered Life that a disguised Boozer approached him at a fancy party in New York, bought him a drink, invited him for a carriage ride, and told him of her adventures abroad. This suggests more than a nodding familiarity between Boozer and Selby.[39]

- ↑ The younger Selby and Holmes were the S. and H. of "S. and H. Publishing" that printed The Countess Pourtales.

- ↑ For example, Snowden says that Sherman's memoir never mentioned Boozer.[50] In fact Sherman did mention "Mrs. Feaster and her two beautiful daughters".[51]

- ↑ The Columbia novelist and local historian Elizabeth Boatwright Coker (1909-1993) suggested a different motive: that Selby may have had an affair with Boozer's mother Amelia Feaster and Boozer might have been aware of it.[55]

- ↑ In his Memorabilia, Selby describes the tar-and-feathering of a man who persisted in criticizing "negro slavery".[33]

Citations

- 1 2 3 TheStateObit 1907, p. 5.

- 1 2 Margaret 1850.

- ↑ TheStateObit 1907.

- ↑ TheSouthCarolinian 2023.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 101,198.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 Snowden, Bennett & Anderson 1993, p. 355.

- ↑ Lucas 2000, p. 128.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 101-103.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 103-105.

- ↑ TypicalPhoenix 1865, p. 1.

- 1 2 TheDailyPhoenix 2023.

- ↑ Simms 2011.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 105-109.

- 1 2 Selby 1905, p. 143.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 142.

- 1 2 Selby 1905, p. 108.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 76,124.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 133.

- ↑ AliceObit 1914, p. 2.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 115-116.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 110-114.

- ↑ Henry 1914, p. 77.

- ↑ Salsi & Sims 2003, p. 104.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 3.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 6.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 4.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 141.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 63.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 20.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 72.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 38.

- 1 2 Selby 1905, p. 131.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 32.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 5.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 106-107.

- ↑ Selby 1905, p. 154-197.

- 1 2 Pollack 2017, p. 67.

- ↑ Selby 1878, p. 41.

- ↑ Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 18-50.

- ↑ Elmore 2014, p. 66.

- ↑ Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 38-41.

- ↑ Pollack 2017, p. 173.

- ↑ Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 41-46.

- 1 2 Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 51-60.

- ↑ Pollack 2017, p. 146.

- ↑ Pollack 2017, p. 174-175.

- ↑ Snowden, Bennett & Anderson 1993, p. 85.

- ↑ Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 5-17.

- ↑ Selby & Snowden 1915, p. 6.

- ↑ Sherman 1875, p. 295.

- ↑ Greene 2022.

- 1 2 Snowden, Bennett & Anderson 1993, p. 89.

- ↑ Pollack 2017, p. 221.

- ↑ Elmore 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Bancroft 1959, p. 240.

- 1 2 Bancroft 1959, p. 243.

References

- Bancroft, Frederic (1959) [1931]. Slave trading in the Old South. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing. OCLC 1046300142.

- Elmore, Tom (2014). The Scandalous Lives of Carolina Belles. Charleston, S.C.: History Press. ISBN 9781626195103.

- Greene, Harlan (2022). "John Bennett". South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Henry, Charles S. (July 1914). "Columbia, S.C. News". The Typographical Journal. Vol. 45, no. 1. Indianapolis, Indiana: International Typographical Union. p. 77. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- Lucas, Marion Brunson (2000) [1976]. Sherman and the burning of Columbia. College Station: Texas A&M Univ. Press. ISBN 1570033587.

- Pollack, Deborah C. (2017). Bad Scarlett. Peppertree Press. ISBN 9781614934943.

- Salsi, Lynn Sims; Sims, Margaret (2003). Columbia History of a Southern Capital. Charleston, SC: Acadia. ISBN 9780738524115.

- Selby, Julian Augustus (1878). A Checkered Life. Columbia, S.C.: Office of the Daily Phoenix. OCLC 19840404.

- Selby, Julian Augustus (1905). Memorabilia. Columbia, S.C.: R. L. Bryan Co. ASIN B07DTJDLBM.

- Selby, Julian Augustus; Snowden, Yates (1915). The Countess Pourtales. Columbia, S.C.: S. and H. Publishing Co. OCLC 1959923.

- Sherman, William Tecumseh (1875). Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. Vol. 2. London: Henry S. King and Co. p. 295.

- Simms, William Gilmore (2011). A City Laid Waste. Columbia, S.C.: Univ. of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781643361284.

- Snowden, Yates; Bennett, John C.; Anderson, Mary Crow (1993). Two Scholarly Friends. Columbia, S.C.: Univ. of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0872499618.

- "1623-1625 Main Street". Historic Columbia. 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "End of a Long and Useful Life - Julian Selby". The Herald and News. Newbury, S.C. 16 April 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- "Margaret A. and Julian Selby", United States census, 1850; Columbia, Richland Cty., SC; roll M432 Source House Number 158, line 41. Retrieved on 12 August 2023.

- "Mrs. Alice Elizabeth Peers Selby". The State Newspaper. Columbia, S.C. 15 June 1914. p. 2.

- "Phoenix of July 31,1865". Chronicling America; Historic American Newspapers. National Endowment for the Humanities. 1865. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- "The Daily Phoenix". Chronicling America; Historic American Newspapers. National Endowment for the Humanities. 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- "The South Carolinian". Chronicling America; Historic American Newspapers. National Endowment for the Humanities. 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.