| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

The Köprülü era (Turkish: Köprülüler Devri) (c. 1656–1703) was a period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were frequently dominated by a series of grand viziers from the Köprülü family. The Köprülü era is sometimes more narrowly defined as the period from 1656 to 1683, as it was during those years that members of the family held the office of grand vizier uninterruptedly, while for the remainder of the period they occupied it only sporadically.[1]

The Köprülüs were generally skilled administrators and are credited with reviving the empire's fortunes after a period of military defeat and economic instability. Numerous reforms were instituted under their rule, which enabled the empire to resolve its budget crisis and stamp out factional conflict in the empire.[2]

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha

The Köprülü rise to power was precipitated by a political crisis resulting from the government's financial struggles combined with a pressing need to break the Venetian blockade of the Dardanelles in the ongoing Cretan War.[3][4] Thus, in September 1656 Valide Sultan Turhan Hatice selected Köprülü Mehmed Pasha as grand vizier, as well as guaranteeing him absolute security of office. She hoped that a political alliance between the two of them could restore the fortunes of the Ottoman state.[5] Köprülü was ultimately successful; his reforms enabled the empire to break the Venetian blockade and to restore authority to the rebellious Transylvania. However, these gains came at a heavy cost in life, as the grand vizier carried out multiple massacres of soldiers and officers he perceived to be disloyal. Regarded as unjust by many, these purges triggered a major revolt in 1658, led by Abaza Hasan Pasha. Following the suppression of this rebellion, the Köprülü family remained unchallenged politically until their failure to conquer Vienna in 1683. Köprülü Mehmed himself died in 1661, when he was succeeded in office by his son Fazıl Ahmed Pasha.[6]

Fazıl Ahmed Pasha and Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha

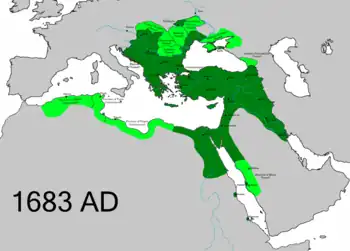

Fazıl Ahmed Pasha (1661–1676) continued the reforming tradition of his father, and also engaged in numerous military campaigns against the empire's European neighbors. He conquered Nové Zámky (Turkish Uyvar) from the Habsburgs in 1663, concluded the Cretan War with the conquest of Heraklion (Kandiye) in 1669, and annexed Kamianets-Podilskyi (Kamaniçe) from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1672. This policy of aggressive expansion, continued by Fazıl Ahmed's brother-in-law and successor Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha, expanded the borders of the Ottoman Empire to their greatest extent in Europe.[7] Yet it also facilitated the formation of a large international coalition to oppose the Ottomans, leading to defeats and territorial losses following the disastrous Siege of Vienna in 1683.[8] For his failure, Kara Mustafa Pasha was executed by Sultan Mehmed IV, leading to a break in Köprülü rule. During the subsequent period of warfare, members of the Köprülü household occasionally regained the grand vizierate - for instance Fazıl Mustafa Pasha (1689–1691) and Amcazade Hüseyin Pasha (1697–1702), yet they never again achieved as firm a grip on power as they had enjoyed before 1683.

The War of the Holy League

In the subsequent conflict, the Ottomans struggled under the strain of multi-front warfare with the Habsburgs, the princes of the Holy Roman Empire, Venice, Poland–Lithuania, and Russia. After a series of defeats culminating in the loss of Hungary, the Ottomans managed to stabilize their position, reconquering Belgrade in 1690. However, attempts to regain further territory were unsuccessful, and following defeat in the Battle of Zenta in 1697 they were forced to recognize their inability to reconquer the lost Hungarian lands.[9]

In 1699, under the terms of the resulting Treaty of Karlowitz, the Ottomans ceded all of Hungary and Transylvania to the Habsburgs, with the exception of the Banat region. Morea was transferred to Venice, while Podolia was returned to Poland–Lithuania. These concessions marked a major geopolitical shift in Eastern Europe, namely the end of Ottoman imperial expansion. The Ottomans henceforth adopted a defensive policy on the Danube frontier, and were largely successful in maintaining its integrity throughout the eighteenth century.[10] This period, contrary to the views of earlier generations of historians, is no longer viewed as one of decline.[11]

Economic and social developments

The Köprülü era is also noteworthy for several other developments in the Ottoman Empire. Fazıl Ahmed Pasha's tenure in office coincided with the height of the Kadızadeli religious movement in Istanbul. Its leader, Vani Mehmed Efendi, was made court preacher for Sultan Mehmed IV and played a role in shaping imperial policy and increasing religious conservatism. Based upon the Islamic principle of "enjoining good and forbidding wrong," the Kadızadelis believed it was the duty of all believers to actively enforce religious orthodoxy, and to combat innovations in religious practice (bidʿah). They thus opposed the practice of Sufi worship, as well as other habits such as drinking and smoking. Despite the court's approval of much of the Kadızadeli program, the group was regarded negatively by many of the empire's Muslim intellectuals, such as Kâtib Çelebi and Mustafa Naima, who viewed them as backwards-thinking and overly reactionary.[12] Following the Siege of Vienna, Vani Mehmed Efendi fell out of favor and was exiled from court, his movement no longer receiving imperial support.[13]

The Ottoman Empire was profoundly affected by reforms carried out during the 1683-99 War of the Holy League. After the initial shock of the loss of Hungary, the empire's leadership began an enthusiastic process of reform intended to strengthen the state's military and fiscal organization. This included the construction of a fleet of modern galleons, the legalization and taxation of the sale of tobacco as well as of other luxury goods, a reform of waqf finances and tax collection, a purge of defunct janissary payrolls, reform in the method of cizye collection, and the sale of life-term tax farms known as malikâne. These measures enabled the Ottoman Empire to resolve its budget deficits and enter the eighteenth century with a considerable surplus.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, 253.

- ↑ Finkel, Osman's Dream, 281.

- ↑ Finkel, Osman's Dream, 252.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık. Devlet-i 'Aliyye: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu Üzerine Araştırmalar - III, Köprülüler Devri, [Devlet-i 'Aliyye: Studies on the Ottoman Empire - III, Köprülü Era] (in Turkish) (Istanbul: Türkiye Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2015), pp. 17-28.

- ↑ Leslie Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, (Oxford University Press: 1993), pp. 256-7.

- ↑ İnalcık, Devlet-i 'Aliyye, pp. 27-39.

- ↑ İnalcık, Devlet-i 'Aliyye, pp. 83-111.

- ↑ Rhoads Murphey, Ottoman Warfare, 1500-1700, (Rutgers University Press, 1999) pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Gábor Ágoston, Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 202.

- ↑ Virginia Aksan, Ottoman Wars, 1700-1860: An Empire Besieged, (Pearson Education Limited, 2007) 28.

- ↑ Hathaway, Jane (2008). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516-1800. Pearson Education Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-582-41899-8.

historians of the Ottoman Empire have rejected the narrative of decline in favor of one of crisis and adaptation

- Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-107-41144-9.

Ottomanist historians have produced several works in the last decades, revising the traditional understanding of this period from various angles, some of which were not even considered as topics of historical inquiry in the mid-twentieth century. Thanks to these works, the conventional narrative of Ottoman history – that in the late sixteenth century the Ottoman Empire entered a prolonged period of decline marked by steadily increasing military decay and institutional corruption – has been discarded.

- Woodhead, Christine (2011). "Introduction". In Christine Woodhead (ed.). The Ottoman World. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-44492-7.

Ottomanist historians have largely jettisoned the notion of a post-1600 'decline'

- Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-107-41144-9.

- ↑ Lewis V. Thomas, A Study of Naima, Edited by Norman Itzkowitz. (New York: New York University Press, 1972), pp. 106-110.

- ↑ Marc David Baer, Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 105, 221-227.

- ↑ Rhoads Murphey, "Continuity and Discontinuity in Ottoman Administrative Theory and Practice during the Late Seventeenth Century," Poetics Today 14 (1993): 419-443.

- Linda Darling, Revenue-Raising and Legitimacy, Tax Collection and Finance Administration in the Ottoman Empire, 1560-1660, (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1996) 239.

- Finkel, Osman's Dream, p. 325-6.

Bibliography

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005). Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aksan, Virginia (2007). Ottoman Wars, 1700-1860: An Empire Besieged. Pearson Education Limited.

- Baer, Marc David (2008). Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979783-7.

- Darling, Linda (1996). Revenue-Raising and Legitimacy, Tax Collection and Finance Administration in the Ottoman Empire, 1560-1660. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- Hathaway, Jane (2008). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516-1800. Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 978-0-582-41899-8.

- Peirce, Leslie (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

- Rhoads, Murphey (1993). "Continuity and Discontinuity in Ottoman Administrative Theory and Practice during the Late Seventeenth Century". Poetics Today. 14: 419–443.

- Rhoads, Murphey (1999). Ottoman Warfare, 1500-1700. Rutgers University Press.

- Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-41144-9.

- Thomas, Lewis V. (1972). Norman Itzkowitz (ed.). A Study of Naima. New York: New York University Press.

- Woodhead, Christine (2011). The Ottoman World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44492-7.

Further reading

General histories

Monographs

- Abou-El-Haj, Rifa'at Ali (1984). The 1703 Rebellion and the Structure of Ottoman Politics. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te İstanbul.

- Baer, Marc David (2008). Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979783-7.