_Sandaime_Ichikawa_Yaoz%C5%8D.jpg.webp)

Kabukidō Enkyō (歌舞伎堂 艶鏡, fl. c. 1796) was a Japanese artist who designed ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Nothing is known of Enkyō's life, and only seven of his works are known, all of which are ōkubi yakusha-e, bust portrait prints of kabuki actors. Scholars divide them into two groups based on differences in the signatures, and the second group appears to be a set, as the prints depict three brothers from the same play. Enkyō's identity has been subject to speculation: a student of Sharaku's, even Sharaku himself, or a kyōgen playwright.

Background

Ukiyo-e art flourished in Japan during the Edo period from the 17th to 19th centuries. Its subjects were of the courtesans, kabuki actors, and others associated with the ukiyo hedonistic "floating world" lifestyle of the pleasure districts. Mass-produced woodblock prints were a major form of the genre.[1] After the mid-18th century, full-colour nishiki-e prints became common, printed with a large number of woodblocks, one for each colour.[2] Shunshō of the Katsukawa school introduced the ōkubi-e "large-headed picture" in the 1760s.[3] He and his school soon popularized ōkubi yakusha-e, prints of actors[4] from kabuki, a flamboyant theatrical form that enjoyed popularity with the masses.[5]

The enigmatic print designer Sharaku's works are amongst ukiyo-e's best known. They began to appear suddenly in 1794. Sharaku introduced a greater level of realism into his yakusha-e prints that emphasized the differences between the actor and the portrayed character.[6] The expressive, contorted faces he depicted contrasted sharply with the serene, mask-like faces more common to artists such as Harunobu or Utamaro.[7] Sharaku's work found resistance, and in 1795 his output ceased as mysteriously as it had appeared; his identity is still unknown.[8] Kabukidō Enkyō's ōkubi yakusha-e appeared sixteen months after Sharaku's work ceased.[9] Nothing is known of Enkyō's life or identity beyond the bare fact that he flourished as an artist in Japan at the end of the eighteenth century.[10]

Works

Enkyō appears not to have been a prolific artist. Seven portraits were confirmed as Enkyō's in the early 20th century, and no further works have been discovered.[11] The ōban-size[lower-alpha 1][12] yakusha-e woodblock print portraits of kabuki actors are all ōkubi-e bust portraits dated to c. 1796. None bear a publisher's seal. Scholars divide them into two groups based on differences in the artist's seal.[13]

First group

The first group bears the seal "Kabukidō Enkyō Ga" (歌舞伎堂艶鏡画, "drawn by Kabukidō Enkyō") and is made up of:[13]

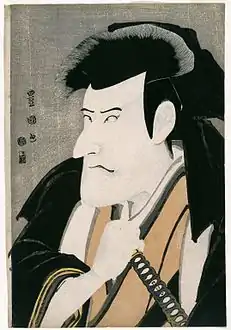

- Ichikawa Omezō I (初代市川男女蔵 Shodai Ichikawa Omezō)

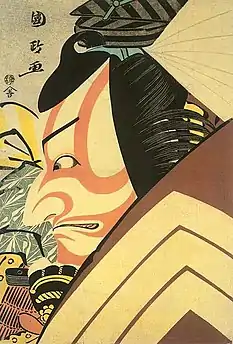

- Ichikawa Yaozō III (三代目市川八百蔵 Sandaime Ichikawa Yaozō)

- Sawamura Sōjūrō III (三代目沢村宗十郎 Sandaime Sawamura Sōjūrō)

- Nakayama Tomisaburō I (初代中山富三郎 Shodai Nakayama Tomisaburō).

- Actor portraits by Kabukidō Enkyō

_Ichikawa_Omez%C5%8D_I.jpg.webp) Ichikawa Omezō I

Ichikawa Omezō I_Sandaime_Ichikawa_Yaoz%C5%8D.jpg.webp) Ichikawa Yaozō III

Ichikawa Yaozō III Sawamura Sōjūrō III

Sawamura Sōjūrō III_Shodai_Nakayama_Tomisabur%C5%8D.jpg.webp) Nakayama Tomisaburō I

Nakayama Tomisaburō I

_Shosei_Ichikawa_Omez%C5%8D_no_Yakko_Ippei.jpg.webp)

Ichikawa Omezō I portrays a character from the kabuki play Sumida no Haru Geisha Katagi[lower-alpha 2] (1796).[14] Enkyō's depiction of the warrior-like character invites comparison to Sharaku's portrait of the same, though they achieve different effects.[11] Sharaku's has greater depth of expression, while Enkyō's simpler, more greatly exaggerated depiction with larger eyebrows leaves a strong immediate expression.[14] Enkyō gives his Omezō a facetious expression and delineates his rounder features with a milder line.[11] He colours the irises with thinned sumi ink, a technique Enkyō may have borrowed from Shun'ei, Toyokuni, and Kunimasa, who had introduced it about that time.[12] Evidence of the effort put into the design can be inferred from other fine details such as touches of red on the earlobes and the colouring on the shaved part of the forehead.[11]

It has been suggested the Ichikawa Yaozō III portrait is of a key character in the play Katakiuchi Noriyaibanashi[lower-alpha 3] (1794). It uses thinned ink to colour the irises, and the composition appears to bear the influence of Sharaku in its attempt at greater realism. The positioning of Enkyō's Nakayama Tomisaburō I, with the actor's hand on his collar, bears strong resemblance to Sharaku's version in the role of Miyagino from Katakiuchi Noriyaibanashi, suggesting Enkyō likely used Sharaku's print as a reference.[15]

Second group

The other three prints appear to make a set as they depict three brothers from the same episode of the same play. The set is made up of:[13]

- Nakamura Nakazō II as Matsuōmaru (二代中村仲蔵の松王丸 Nidaime Nakamura Nakazō no Matsuōmaru)

- Ichikawa Yaozō III as Umeōmaru (三代市川八百蔵の梅王丸 Sandaime Ichikawa Yaozō no Umeō)

- Nakamura Noshio II as Sakuramaru (二代中村野塩の桜丸 Nidaime Nakamura Noshio no Sakuramaru)

- Portraits from Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami by Kabukidō Enkyō

.jpg.webp) Nakamura Nakazō II as Matsuōmaru

Nakamura Nakazō II as Matsuōmaru_Sandaime_Ichikawa_Yaoz%C5%8D_no_Ume-%C5%8Cmaru.jpg.webp) Ichikawa Yaozō III as Umeōmaru

Ichikawa Yaozō III as Umeōmaru.jpg.webp) Nakamura Noshio II as Sakuramaru

Nakamura Noshio II as Sakuramaru

This set shows a stronger Toyokuni influence, rather than Sharaku; while basically striving for realism, there is an idealizing tendency in the rendering of the facial expressions.[11] The prints depict actors in the roles of three brothers from the "Kuruma-biki"[lower-alpha 4] episode[11] of the play Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (1796).[13] The scene depicts Umeōmaru and Sakuramaru waiting in ambush for Fujiwara no Shihei. Their brother Matsuōmaru, who is loyal to Shihei, foils their plot.[11] He appears in the portrait with a protruding beak-like noese and his hair brushed back at the sides. He wears a hat, carries a spear, and wears a check-patterned robe with a set of h-shaped genji-mon crests on them, indicating a chapter from the Genji Monogatari.[16] The Nakamura Noshio II has no seal, and the other two bear the seal "Kabukidō Ga" (歌舞伎鏡画, "drawn by Kabukidō").[13] The print of Nakamura Noshio II as Sakuramaru depicts the youngest of the three brothers, a romantic character whose symbol is the sakura cherry blossom. The character was sometimes performed by an onnagata, an actor specializing in female roles.[11]

Identity

Enkyō's identity is uncertain.[10] There is a brief mention of him in the Ukiyo-e Ruikō, the earliest collection of commentaries and biographies on ukiyo-e artists, begun c. 1790 by Ōta Nanpo (1749–1823). Its single line mentions him as a portraitist who lasted merely half a year, and omits the name Enkyō.[lower-alpha 5][17]

Some have seen Enkyō as a student and perhaps the sole successor of Sharaku.[10] There are no records of ukiyo-e artists other than Sharaku and Enkyō making aiban-sized ōkubi-e yakusha-e during the Edo period.[9] The German writer Julius Kurth asserted Enkyō was Sharaku, who had assumed a new identity to revive his career. The American Arthur Davison Ficke called this idea "an alluring but somewhat fantastic theory, which neither the documentary nor the internal evidence ... adequately supports",[18] and James A. Michener agreed this was a "fanciful theory ... but nothing in the artistic content of Kabukidō's prints supports this wild guess", though "some of Sharaku's later triptychs ... are occasionally as dull as known Kabukidōs".[19]

Hiroshi Matsuki proposed attributing 11 of Sharaku's third-period works to Enkyō, using "Morellian" techniques to compare minor details of the artist's style.[20] These works are the only aiban-sized ōkubi yakusha-e of Sharaku's third period.[lower-alpha 6] Amongst the details that set these works apart from Sharaku's earlier and later ones, five of these prints feature clearly visible ears, which are drawn with six lines, whereas those of Sharaku's other works are drawn with five lines.[21] Given that Enkyō's works appeared sixteen months after Sharaku's, differences in approach such as Enkyō's thicker line and rounder eyes can be attributed to evolution of the artist's style.[9]

Others have seen the similarities with Sharaku as superficial, and point to differences in technique and psychology of the subjects. These scholars have suggested Enkyō's approach may be closer to that of Shunkō's,[10] Shun'ei's, Toyokuni's,[11] or Kunimasa's.[18]

In 1926 ukiyo-e scholar Naonari Ochiai declared Enkyō was the kyōgen playwright Nakamura Jūsuke[lower-alpha 7] (1749 – 4 November 1803).[10] In that case, the work was the hobby of an amateur, and would have lacked a publisher's seal because it would have been printed as a special commission.[11] However, there is no mention of any such connection in the writings of an acquaintance of Nakamura Jusuke's, Ota Nanpo.[17]

Notes

- ↑ Ōban is about 25 by 36 centimetres (10 in × 14 in).

- ↑ 隅田春妓女容性 Sumida no Haru Geisha Katagi

- ↑ 敵討乗合話 Katakiuchi Noriyaibanashi

- ↑ 「車引」 Kuruma-biki

- ↑ 役者似顔のみかきたれど甚しくなければ半年斗にておこなわれず Yakusha nigao nomi kakitaredo hanahanashiku nakereba hantoshi to nite okonowarazu. From the version of c. 1800.[17]

- ↑ Two other aiban-sized prints from Sharaku's third period are not ōkubi-e.

- ↑ 中村重助 Nakamura Jūsuke

References

- ↑ Fitzhugh 1979, p. 27.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Kondō 1956, p. 14.

- ↑ Gotō 1975, p. 81.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Munsterberg 1957, p. 155.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 89–91.

- 1 2 3 Matsuki 1985, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yoshida 1994, p. 171.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai 1981, p. 42.

- 1 2 Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai 1981, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kokusai Ukiyo-e Gakkai 2008, p. 139.

- 1 2 Gotō 1973, p. 133.

- ↑ Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai 1981, p. 43.

- ↑ Stern 1969, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 Katō 1998, p. 10.

- 1 2 Ficke 1917, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Michener 1954, p. 181.

- ↑ Matsuki 1985, pp. 137, 140.

- ↑ Matsuki 1985, pp. 136–137.

Works cited

- Ficke, Arthur Davison (1917). Chats on Japanese Prints. Frederick A. Stokes Company. OCLC 462667666.

- Fitzhugh, Elisabeth West (1979). "A Pigment Census of Ukiyo-E Paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art". Ars Orientalis. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan. 11: 27–38. JSTOR 4629295.

- Gotō, Shigeki, ed. (1973). Ukiyo-e Taikei 浮世絵大系 [Ukiyo-e Compendium] (in Japanese). Vol. 7. Shūeisha.

- Gotō, Shigeki, ed. (1975). Ukiyo-e Taikei 浮世絵大系 [Ukiyo-e Compendium] (in Japanese). Vol. 5. Shueisha. OCLC 703810551.

- Harris, Frederick (2011). Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1098-4.

- Katō, Yoshio (10 January 1998). "Ōta Nanpo ga Kakitometa Ukiyo-e-shi-tachi" 大田南畝が書き留めた浮世絵師達 [The Ukiyo-e Artists that Ōta Nanpo Wrote About]. Ukiyo-e Geijustsu (in Japanese) (126): 3–45.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1997). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3.

- Kokusai Ukiyo-e Gakkai, ed. (2008). Ukiyo-e Daijiten 浮世絵大事典 [Grand Ukiyo-e Dictionary] (in Japanese). Tōkyōdō Shuppan. ISBN 978-4-490-10720-3.

- Kondō, Ichitarō (1956). Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). Translated by Charles S. Terry. Tuttle. OCLC 613198. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Matsuki, Hiroshi (1985). "Sharaku no Nazo to Kagi" 写楽の謎と鍵. In Tsuji, Nobuo (ed.). Sharaku 写楽 [Sharaku]. Ukiyo-e Hakka (ja: 浮世絵八華) [Eight Flowers of Ukiyo-e] (in Japanese). Vol. 4. Heibonsha. ISBN 4-582-66204-8.

- Michener, James Albert (1954). The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0.

- Munsterberg, Hugo (1957). The Arts of Japan: An Illustrated History. Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 9780804800426.

- Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyōkai, ed. (1981). Genshoku Ukiyo-e Dai-hyakkajiten 原色浮世絵大百科事典 [Grand Encyclopaedia of Ukiyo-e in Original Colour] (in Japanese). Vol. 8. Taishūkan Shoten. OCLC 8327141.

- Stern, Harold P. (1969). Master Prints of Japan: Ukiyo-e Hanga. Abrams. OCLC 475701323.

- Yoshida, Teruji, ed. (1994). Ukiyo-e Jiten 浮世絵事典 [Ukiyo-e Dictionary] (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Gabundō. ISBN 978-4-87364-004-4.

External links

Media related to Kabukidō Enkyō at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kabukidō Enkyō at Wikimedia Commons