| Kadimakara australiensis Temporal range: Early Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

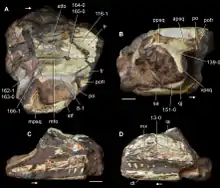

| Holotype (A,B) and referred snout (C,D) of Kadimakara australiensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Family: | †Prolacertidae |

| Genus: | †Kadimakara Bartholomai, 1979 |

| Species: | †K. australiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Kadimakara australiensis Bartholomai, 1979 | |

Kadimakara is an extinct genus of early archosauromorph reptile from the Arcadia Formation of Queensland, Australia. It was seemingly a very close relative of Prolacerta, a carnivorous reptile which possessed a moderately long neck. The generic name Kadimakara references prehistoric creatures from Aboriginal myths which may have been inspired by ice-age megafauna. The specific name K. australiensis relates to the fact that it was found in Australia.[1] Prolacerta and Kadimakara were closely related to the Archosauriformes, a successful group which includes archosaurs such as crocodilians, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs.[2]

Discovery

Kadimakara is only known from parts of the skull. The holotype specimen, QMF 6710, includes the rear part of the skull and a fragment of the right lower jaw. This specimen was recovered in the mid-1970s from L78, a fossil site 72 kilometers southwest of Rolleston, Queensland. The geology of this locale belongs to the Rewan Group of the Lower Arcadia Formation, which has also occasionally been elevated in status to its own formation, the Rewan Formation.[1] The Rewan Formation corresponds to the Induan age at the very beginning of the Triassic Period, about 251 million years ago, when life had only begun to recover from the Permian-Triassic extinction.[2]

An additional specimen was also recovered from the same site, although it was not closely associated with the holotype. This specimen, QMF 6676, consisted of a portion of the snout and lower jaws. None of the bones preserved in this specimen overlapped with those preserved in the holotype. As a result, it cannot be definitively proven that they both belonged to Kadimakara. However, they also lack any particular inconsistencies which would prohibit them from both belonging to the animal.[2] Like other animals preserved in the Rewan Formation, remains of Kadimakara were encrusted in hematite and had to be carefully prepared with thioglycollic acid.[1]

Description

Kadimakara was roughly half the size of its larger relative Prolacerta, but was otherwise quite similar based on the structure of its preserved skull bones.

Holotype

The rear of the skull, as shown by the holotype specimen, preserves several bones of the skull roof, most notably the parietal bones which form the upper surface of the skull past the level of the eyes. These paired bones were boxy in shape and contacted each other at the midline of the skull. In the middle of their suture (line of contact) was a hole known as a pineal foramen, which in some modern reptiles contains a sensory structure colloquially known as a "third eye". Immediately behind this hole was a rectangular lowered area of bone, known as a median fossa. This median fossa is the main feature which can be used to differentiate Kadimakara from its close relative Prolacerta, which either lacks this specific lowered area or has the entire rear part of the skull slightly lowered, depending on the individual. Directly above the eyes were a pair of bones known as frontals; only a small portion of these bones were preserved in the Kadimakara holotype. However, the preserved portion can be seen to stretch along the outer edges of the parietal bones. This means that the parietals had a wedge-like shape when seen from above, and that they stretched forward as far as the level of the orbits. Kadimakara also lacks postparietals, additional bones which form out of the rear part of the parietals in many different types of archosauromorphs. All of these parietal features are also shared by Prolacerta, and their presence (or lack thereof) links Kadimakara with that genus in the family Prolacertidae.[2] A small, wedge-like bone known as a postfrontal formed the upper rear corner of the orbit (eye hole).[1]

The outer edge of each parietal bone contacts a large hole on each side of the skull roof. These holes are known as supratemporal fenestrae. The outer edge of each hole was formed by a multi-pronged bone, although the identity of this bone has been controversial. The original describer of Kadimakara, Alan Bartholomai, considered it a postorbital bone which forms the rear edge of an unusually elongated orbit. In 2016, Martin Ezcurra reinterpreted the bone as a complex forward extension of the squamosal bone. This reinterpretation means that the orbit had a rounder and much less unusual shape than that of Bartholomai's original reconstruction, as the actual postorbital bone was positioned further forward on the skull. Unfortunately, the postorbital is mostly lost, with only a small sliver of bone still present in the specimen. Nevertheless, this postorbital sliver can be seen to contact a supratemporal fenestra, omitting the preserved postfrontal bone from contact with the hole.[2]

This reinterpretation has several implications for bone identifications in the rest of the skull. The ventral process (lower branch) of the squamosal, which extends onto the cheek region of the skull, contacts a smaller crescent-shaped bone near the jaw joint. Under Bartholomai's interpretation, this bone was a fragment of the jugal (cheek bone), but Ezcurra reinterpreted it as a strap-like quadratojugal bone, which was near the jaw joint.[2] Regardless of these interpretations, the rear branch of the jugal would not have been long enough to enclose the lower temporal fenestra. The lower temporal fenestra (also known as the infratemporal fenestra) was typically a large hole on the side of the skull, although it was not completely enclosed from below in many lepidosaurs (the group of reptiles containing lizards, snakes, and the tuatara) and a few archosauromorphs (such as Prolacerta and Kadimakara). In these reptiles, the lower temporal fenestra attained an arch-like shape. The Kadimakara holotype has also preserved fragments of the braincase and the rear part of the palate. The rear part of the shallow lower jaw was also preserved.[1]

Referred snout

As this specimen is not definitively proven to belong to Kadimakara, many of its features may not necessarily apply to the genus. However, its referral to Kadimakara is likely legitimate due to the fact that the snout bones closely resemble those of Prolacerta. The maxilla (the main toothed bone of the snout) was covered in shallow longitudinal furrows but otherwise had a conventional design, with a large main body and a wedge-like prong extending backwards to contact the jugal bone. Several teeth have also been preserved attached to the maxilla. These teeth are sharp, curved, and flattened from the side, indicating that Kadimakara was a carnivorous reptile. The teeth are set in deep sockets and fused to the bone in several areas. The rear edge of the maxilla clearly connects to a smaller bone known as a lacrimal, which forms the front edge of the orbit. The upper side of the snout was formed by a pair of large bones known as nasals which presumably contacted the frontals in an area which has not been preserved. The middle part of the shallow lower jaw was also preserved, including teeth similar to those of the maxilla.[1]

Classification

The classification of Kadimakara and Prolacerta has gone through much revision in the past. Bartholomai's original description was published at a time when Prolacerta was undergoing significant analysis. Prior to the mid-1970s, Prolacerta was believed to be an 'eosuchian' , ancestral to all modern reptiles. However, a 1975 analysis by Chris Gow provided a more specific explanation, arguing that the teeth of Prolacerta (and Kadimakara, as Bartholomai notes) were particularly similar to those of 'thecodonts', a group of carnivorous reptiles now known as archosauromorphs. Subsequent studies published in the late 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s supported this interpretation, with Bartholomai's 1979 description of Kadimakara being among the earliest to support Gow's claim.[1]

Over time, cladistic work refined and revised the group Thecodontia, replacing it with the more well-defined group Archosauromorpha, which refers to all reptiles closer to crocodilians and dinosaurs than to lizards and other lepidosaurs. During this transition, Kadimakara and Prolacerta were kept in a group known as Prolacertiformes, which contained other long-necked early archosauromorphs such as Protorosaurus, Macrocnemus, and Tanystropheus.[3]

This changed in 1998, when a study by David Dilkes found that Prolacertiformes was a polyphyletic group, consisting of various reptiles only distantly related to each other. Most notably, Prolacerta was found to be more closely related to the advanced Archosauriformes rather than Protorosaurus and other long necked basal archosauromorphs (collectively termed "protorosaurs").[4] Unfortunately, Kadimakara was omitted from this analysis as well as earlier analyses focusing on Prolacertiformes, such as Nour-Eddine Jalil's 1997 description of Jesairosaurus. The reasoning behind these omissions mainly related to the incompleteness of Kadimakara remains.[3] As a result, it was unknown whether Kadimakara was legitimately a close relative of Prolacerta or simply an unrelated basal archosauromorph incorrectly allied with it, as is the case with the protorosaurs. This uncertainty was magnified when several studies in the late 2000s claimed that Kadimakara was simply a pair of misidentified specimens of Prolacerta.[5][6]

Kadimakara was finally featured in phylogenetic analyses in 2016 during Martin Ezcurra's broad study on archosauromorphs. In addition, Ezcurra redescribed and reinterpreted the genus and was able to find evidence that it was not in fact synonymous with Prolacerta. His study featured three different phylogenetic analyses. Analysis 1 only concerned holotypes of sampled reptiles, analysis 2 concerned all known specimens (a complete hypodigm), and analysis 3 was identical to analysis 2, except with a few fragmentary taxa excluded. Due to the uncertainty of the referred snout's legitimacy, Kadimakara was actually given two different samples. One sample only consisted of the holotype while the other sample consisted of both the holotype and the referred snout. As a result, analysis 1 only included the holotype sample, while analyses 2 and 3 only included the (holotype + referred) sample. In each of the three analyses, Kadimakara was placed as the sister taxon to Prolacerta, with these two genera forming the family Prolacertidae, positioned near Archosauriformes as Dilkes (1998) and other studies claimed previously.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bartholomai, Alan (1979). "New lizard-like reptiles from the Early Triassic of Queensland". Alcheringa. 3 (3): 225–234. doi:10.1080/03115517908527795.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- 1 2 Nour-Eddine Jalil (1997). "A new prolacertiform diapsid from the Triassic of North Africa and the interrelationships of the Prolacertiformes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (3): 506–525. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010998. JSTOR 4523832.

- ↑ Dilkes, David W. (1998-04-29). "The early Triassic rhynchosaur Mesosuchus browni and the interrelationships of basal archosauromorph reptiles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 353 (1368): 501–541. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0225. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692244.

- ↑ Borsuk-Białynicka, Magdalena; Evans, Susan (2009). "A long-necked archosauromorph from the early Triassic of Poland" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 65: 203–234.

- ↑ Evans, Susan; Jones, Marc (2010). "The Origin, Early History and Diversification of Lepidosauromorph Reptiles". New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. Vol. 132. pp. 27–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10311-7_2. ISBN 978-3-642-10310-0.