Karl Struss | |

|---|---|

Photographer and cinematographer Karl Struss in 1912, photographed by Clarence H. White | |

| Born | November 30, 1886 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | December 15, 1981 (aged 95) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Burial place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Occupation | Cinematographer |

| Title | A.S.C. |

| Awards | Academy Award for Best Cinematography 1928 Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (co-winner Charles Rosher) |

Karl Struss, A.S.C. (November 30, 1886 – December 15, 1981) was an American photographer and a cinematographer of the 1900s through the 1950s. He was also one of the earliest pioneers of 3-D films. While he mostly worked on films, such as F.W. Murnau's Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans and Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator and Limelight, he was also one of the cinematographers for the television series Broken Arrow and photographed 19 episodes of My Friend Flicka.

Life and career

Karl Struss was born in New York City in 1886. After an illness in high school, Karl's father, Henry, removed his son from school and placed him as a labor operator at Seybel & Struss bonnet wire factory.[1] He began to develop an interest in photography, experimenting with an 8x10 camera, and beginning in 1908, attended Clarence H. White's evening art photography course at Teachers College at Columbia University, concluding his studies in 1912.[2]

Early in his studies, he explored the properties of camera lenses and eventually invented, in 1909, what he attempted to patent as the Struss Pictorial Lens, a soft-focus lens.[3] This lens was considered popular with pictorial photographers of the time. The Struss Pictorial lens was the first soft-focus lens introduced into the motion picture industry, in 1916.[4]

Initially, Struss gained attention in the photo world when 12 of his pictorial works were chosen by Alfred Stieglitz for the Albright Art Gallery International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography in 1910. This was the final exhibition of the Photo-Secession, an organization that promoted photography as fine art.[4]

Struss's reputation was solidified by his inclusion in the exhibition "What the Camera Does in the Hand of the Artist" at the Newark Art Museum, held in April 1911, and an invitation by the Teacher's College for Struss to organize a one-person exhibition of his views of New York City as well as to teach White's course in the summer of 1912 while White was away.[5] Struss was invited by Stieglitz to join the Photo-Secession in 1912, which led to the publication of Struss's photographs in the group's magazine Camera Work. In 1913, Struss, in collaboration with Edward Dickson, Clarence White, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Paul Anderson, began their own publication, Platinum Print. In 1914, he resigned his position at the family business and asserted his identity as a professional photographer by assuming Clarence White's former studio space in June of that year [6]

At the suggestion of Coburn, Struss submitted prints to the American Invitational Section of the annual exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society in London, initiating an exhibiting practice he would continue into the 1920s.[7] He also participated in numerous exhibitions organized by photography clubs and other associations, including the Pittsburgh Salon of National Photographic Art and the annual photography display organized by the Philadelphia department store Wanamaker's.[8] As Struss continued his exhibitions and specialized commissions, he produced commercial photography for magazines, including Vogue, Vanity Fair, and Harper's Bazaar.[4] (However, he was quick to insist that he was not doing fashion photography.) His photographic practice was interrupted by World War I. In 1917, he registered for the draft and then enlisted with the aim of fulfilling his military service through photography.[9]

He trained to teach aerial photography, but an investigation into Struss's German affiliations launched by the Military Intelligence Department led to his demotion from the rank of sergeant to private; after a period in confinement in Ithaca, New York, where he had originally gone to teach in the new School of Military Aeronautics, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth to serve as a prison guard and then as a file clerk.[10] In the latter role, he took up photography again, documenting the prisoners. Near the close of the war, in an attempt to clear his record of rumors of anti-Americanism, he applied and was accepted into Officer's Training Camp at the rank of corporal.[11]

While Struss eventually received an honorable discharge, he likely was disinclined to resume his former roles in New York because of the fracturing of many of his professional relationships in the wake of the military investigation.[12]

In 1919, after his discharge, he moved to Los Angeles and signed with Cecil B. DeMille as a cameraman, initially for the film For Better, For Worse, starring Gloria Swanson, followed by another Swanson film, Male and Female, and leading to a two-year contract with the studio.[13] In early 1921, he married Ethel Wall, who helped to support him in his photographic work independent of the film studios, which included pictorial views set in California.[14] In the 1920s, Struss worked on such films as Ben-Hur and F.W. Murnau's Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. In 1927, he contracted with United Artists, where he worked with D.W. Griffith on films such as Drums of Love and filmed Mary Pickford's first sound film, Coquette.[15] He continued his experimental work with camera technology, developing the "Lupe Light" and a new bracket system for the Bell & Howell camera.[16]

From 1931 through 1945, Struss worked as a cameraman for Paramount, where he worked on a variety of material, including films featuring Mae West, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour.[17] Struss also aimed to shape the field through publishing: for example, in 1934, he wrote "Photographic Modernism and the Cinematographer" for American Cinematographer. Struss was admitted to the American Society of Cinematographers and was a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts.[18] In 1949, while working as a freelancer, he began his work in "stereo cinematography", becoming one of the early proponents of that art form. Unfortunately, he did most of his 3-D film work in Italy, and none of his films were released in 3-D in the United States.

Struss's photographic archive of exhibition prints, film stills, negatives, and papers (3 linear feet of materials) is available at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, located in Fort Worth, Texas.[19]

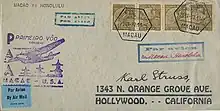

Aside from his work as a photographer and cinematographer, Struss had a keen interest in philately with a particular focus on the first transpacific airmail flights, making commemorative covers for both the initial November 22, 1935 airmail flight from San Francisco to Honolulu and on to Manila and for the first flights on the extension of the service, from Manila to Hong Kong and Macau, starting April 1937. These signed covers are on his personal stationery showing his address at the time as 1343 N. Orange Grove Ave., in Hollywood (see illustration).[20]

Awards

In his career, Struss was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography four times. The first time, and the only time he won, was for F.W. Murnau's Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans in 1929, sharing that award with Charles Rosher. He was nominated again in 1932 for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in 1934 for The Sign of the Cross, and in 1942 for Aloma of the South Seas with Wilfred M. Cline, A.S.C. and William E. Snyder, A.S.C.

Selected filmography

- Forbidden Fruit (1921) with Agnes Ayres

- Saturday Night (1922) with Conrad Nagel and Leatrice Joy

- Thorns and Orange Blossoms (1922)

- Rich Men's Wives (1922)

- Mothers-in-Law (1923)

- Poor Men's Wives (1923)

- The Legend of Hollywood (1924)

- Ben-Hur (1925) with Ramon Navarro

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) with Janet Gaynor

- The Battle of the Sexes (1928) with Jean Hersholt

- Lady of the Pavements (1929) with Lupe Vélez

- Coquette (1929) with Mary Pickford

- The Taming of the Shrew (1929) with Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford

- Abraham Lincoln (1930) with Walter Huston

- Skippy (1931) with Jackie Cooper

- Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) with Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins

- The Sign of the Cross (1932) with Fredric March and Charles Laughton

- Island of Lost Souls (1932) with Charles Laughton and Bela Lugosi

- The Story of Temple Drake (1933) with Miriam Hopkins

- One Sunday Afternoon (1933) with Gary Cooper and Fay Wray

- Four Frightened People (1934) with Claudette Colbert

- Belle of the Nineties (1934) with Mae West

- The Pursuit of Happiness (1934) with Francis Lederer and Joan Bennett

- Goin' to Town (1935) with Mae West

- Every Day's a Holiday (1937) with Mae West

- Zenobia (1939) with Oliver Hardy and Harry Langdon

- Gone with the Wind (1939) with Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh (Technicolor tests only, uncredited)

- The Great Dictator (1940) with Charles Chaplin and Paulette Goddard

- Journey into Fear (1943) with Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten

- Frenchman's Creek (1944) with Joan Fontaine

- Wonder Man (1945) with Danny Kaye

- Suspense (1946) with Belita and Barry Sullivan

- Heaven Only Knows (1947) with Robert Cummings

- Rocketship X-M (1950) with Lloyd Bridges and Osa Massen

- The Return of Jesse James (1950) with John Ireland and Ann Dvorak

- Lady Possessed (1952) with James Mason

- Limelight (1952) with Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton

- Mohawk (1956), with Scott Brady and Neville Brand

- Kronos (1957), with Jeff Morrow and Barbara Lawrence

- She Devil (1957), with Mari Blanchard and Jack Kelly

- The Fly (1958) with Vincent Price

References

- ↑ McCandless, Barbara; Yochelson, Bonnie; Koszarski, Richard (1995). New York to Hollywood, The Photography of Karl Struss. Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum. pp. 14, 17. ISBN 0-8263-1637-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 19, 92.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 20-21.

- 1 2 3 McCandless, Barbara (1999). Struss, Karl Fischer. Cary, North Carolina: American National Biography. pp. 57–59.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 30.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 33.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 226-228. See the appendix (pp. 225-235) for Struss' Lifetime Exhibition Record

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 35-41.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 43.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 48.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 50.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 181.

- ↑ New York to Hollywood 1995, p. 182-183.

- ↑ Brown, Turner; Partnow, Elaine (1983). "Karl Struss". MacMillan Biographical Encyclopedia of Photographic Artists and Innovators. MacMillan Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-02-517500-6.

- ↑ Amon Carter Museum Library & Archives

- ↑ Covers in the personal collection of Colin Talcroft.

External links

- Biography on 3D Gear website

- Karl Struss at IMDb

- Karl Struss in 1912(portrait by Clarence H. White)

- Karl Struss 1912(by Clarence H. White, courtesy the Amer.Society of Cinematographers)