Kenkoku Daigaku | |

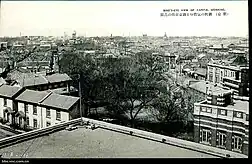

The campus of Kenkoku University. | |

Former names | The Manchurian University |

|---|---|

| Motto | Chinese: "五族協和" Japanese: "ごぞくきょうわ" Korean: "오족협화" |

Motto in English | "Five races under one union" |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | May 1938 |

| Chancellor | Ishiwara Kanji |

| Vice-Chancellor | Sakata Shoichi (1938—1942) Kamezo Odaka (1942—1945) |

| Location | , |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colours | |

| Mascot | Kanto Star (関東の星) |

| |

Kenkoku Daigaku or simply Kendai [ˈkɛndaɪ] was an educational institution in Xinjing (modern Changchun, Jilin province), the capital of Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state in occupied Manchuria during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It operated from May 1938 to August 7, 1945.[1]

Etymology

The name of this academy means "Nation Building University" or "National Foundation University" (建國的原則, 建国の理念). It originated from the period of Northern Zhou.

- Chinese: 建國大學, Jiànguó Dàxué, Kiànkok Tāiha̍k, Gingwok Daaihok

- Japanese: 建国大学, Kenkoku Daigaku

- Korean: 건국대학, Geongug Daehag

- Mongolian: Кенкоку их сургууль, Kyenkoku ikh Surguuli

- Russian: Университет Кэнкоку, Universitet Kenkoku

- Ukrainian: Університет Кенкоку, Universytet Kenkoku[2]

- Belarusian: Універсітэт Кенко, Univiersitet Kienko

- Vietnamese: Kiến-quốc Đại-học, Đại-học Kiến-quốc

- Sanskrit: केन्कोकु विश्वविद्यालय, Kenkoku Vishvavidyaalay

- Hindi: केनकोकू विश्वविद्यालय, Kenkoku Vishvavidyaalay

- German: Universität Kenkoku

- French: Université Kenkoku

- Uyghur: كېنكوكۇ ئۇنىۋېرسىتېتى

- Arabic: جامعة كينكوكو

History

Kenkoku Tai

The Kenkoku Society (Chinese: 建國會, Japanese: 建国会, Kenkoku Tai, "The Society of Nation Building" or "National Foundation Society") was a Japanese secret society founded in April 1926. It was formed by the Nazi sympathizer Takabatake Motoyuki (高畠素之) along with Nagoya Anarchists Uesugi Shinkichi (上杉慎吉) and Akao Bin (赤尾敏).[3] It proclaimed its object to be "the creation of a genuine people's state based on unanimity between the people and the emperor".[4] At its height, the organization reached a nationwide membership of around 120,000.

Its state socialist program included the demand for "the state control of the life of the people in order that among Japanese people there should not be a single unfortunate nor unfully-franchised individual".[4] The organisation embraced Panasianism declaring "The Japanese people standing at the head of the colored people, will bring the world a new civilization". It was at one time in favor of universal suffrage.[4]

The Kenkoku Society worked in close concert with the police to break the miners strike in Tochigi, and other strikes by factory workers in Kanegafuchi, tramway workers in Tokyo, and tenant farmers in Gifu Prefecture. Uesugi soon withdrew in 1927, and Takabatake supporters left following his death in 1928. This left the organization with only around 10,000 members. Mitsuru Toyama (頭山満) of the Black Dragon Society (黒龍会) was appointed honorary chairperson, and Nagata, a former Police Chief, vice-chair. Others of this new influx included Ikihara, Kida, and Sugimoto. Akao was director of the league, which organized gangs of strike breakers and in 1928 bombed the Soviet embassy.[5] Their paper Nipponshugi was virulently anti-communist with slogans such as "Death to Communism, to Russian Bolshevism, and to the Left parties and workers' unions".

Kenkoku Daigaku

Kanto-kun invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident.[6] At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Because sheared off from China by the Kanto-kun in March 1932 and declared an independent country, Manchukuo existed as a client state of Japan on the margins of the international order, recognized by a handful of nations. A pro-Japanese government was installed one year later with Puyi, the last Qing emperor, serving first as nominal regent, and later as the first emperor.[7] Restoration of Puyi to the throne of his Manchu ancestors provided one such symbol, and emphasized Japan's stance in favor of tradition over communism and republicanism, and had tremendous propaganda value.

Although the Kanto-kun was nominally subordinate to the Imperial General Headquarters and the senior staff at the Army General Staff located in Tokyo, its leadership often acted in direct violation of the orders from mainland Japan without suffering any consequence. Conspirators within the junior officer corps of the Kanto-kun plotted and carried out the assassination of Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin in the Huanggutun Incident of 1928. Afterward, the Kanto-kun leadership engineered the Mukden Incident and the subsequent invasion of Manchuria in 1931, in a massive act of insubordination (gekokujo) against the express orders of the political and military leadership based in Tokyo. Presented with the fait accompli, Imperial General Headquarters had little choice but to follow up on the actions of the Kanto-kun with reinforcements in the subsequent Pacification of Manchukuo. The success of the campaign meant that the insubordination of the Kanto-kun was rewarded rather than punished. In 1932, the Kwantung Army was the main force responsible for the foundation of Manchukuo, the puppet state of Japan located in Northeast China and Inner Mongolia. The Kanto-kun played a controlling role in the political administration of the new state as well as in its defense. With the Kwantung Army, administering all aspects of the politics and economic development of the new state, this made the Kwantung Army's commanding officer equivalent to a Governor-General with the authority to approve or countermand any command from Puyi, the nominal Emperor of Manchukuo.[8] As testament to the Kwantung Army's control over the government of Manchukuo, the Commander-in-Chief of the Kwantung Army also served as the Japanese Ambassador of Manchukuo.[9]

From early 1934, the total population of Manchukuo was estimated as 30,880,000, with 6.1 persons the average family, and 122 men for each 100 women. These numbers included 29,510,000 Chinese (96%, which should have included the Manchu people), 590,760 Japanese (2%), 680,000 Koreans (2%), and 98,431 (<1%) of other nationality: White Russians, Mongols, some Europeans. Around 80% of the population was rural. During the existence of Manchukuo, the ethnic balance did not change significantly, except that Japan increased the Korean population in China. From Japanese sources come these numbers: in 1940 the total population in Manchukuo of Longjiang, Rehe, Jilin, Fengtian, and Xing'an provinces at 43,233,954; or an Interior Ministry figure of 31,008,600. Another figure of the period estimated the total population as 36,933,000 residents. The majority of Han Chinese in Manchukuo believed that Manchuria was rightfully part of China, who both passively and violently resisted Japan's propaganda that Manchukuo was a "multinational state".[10] Besides, the South Manchuria Railway Zone and the Korean Peninsula had been under the control of the Japanese Empire since the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Japan's ongoing industrialization and militarization ensured their growing dependence on oil and metal imports from the US.[11] The US sanctions which prevented trade with the United States (which had occupied the Philippines around the same time) resulted in Japan furthering its expansion in the territory of China and Southeast Asia.[12] The invasion of Manchuria, or the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 7 July 1937, are sometimes cited as alternative starting dates for World War II, in contrast with the more commonly accepted date of September 1, 1939.[13]

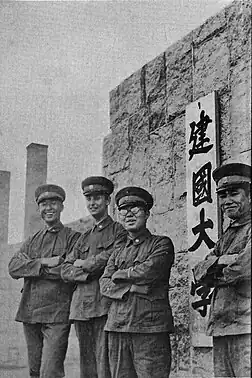

In May 1938, Kenkoku University was founded by an edict of General Kanji Ishiwara in capital Xinjing as the Supreme School of Manchuria (大滿洲帝國最高學府),[14][15] and was run by Professor Sakata Shoichi from Kyoto University.[16] Its purpose was to promote "ethnic harmony" in the region, legitimising and promoting the Japanese occupation.[17] To this end, students were recruited from Japan, China proper, Mongolia, Taiwan, Manchuria, Joseon and Soviet Union.[18] As well as offering free tuition, the University also provided its students with board and lodgings, and a stipend.[19] They were gathered at Kenkoku University under the idea of "Five Races Under One Union" to nurture future leaders in Manchuria. Emphasis was placed on "five races equality" (Japanese: 五族平等) and "academic freedom" (Japanese: 学問の自由), and the students slept and ate together in the dormitory, creating bonds that transcend ethnic groups.[20] However, contrary to the original intention of the Japanese authorities, it turned out that Kenkoku was the incubator for a generation of capable Asian leaders who contributed significantly to shaping East Asian identity after World War II. Multiple students of Kenkoku University later became prominent political figures in South Korea—including later South Korean prime minister Kang Young-hoon—, North Korea and China.[21] A number of influential aikido practitioners trained and taught at the University, including aikido's founder Morihei Ueshiba,[22] Kenji Tomiki, Shigenobu Okumura and Noriaki Inoue.[23] In general, students from Japan, China, Korea, the Soviet Union and Mongolia learned at Kenkoku University under the banner of "the harmony of five ethnicities", and sometimes-surprising friendships were forged at the Japan-run institution, even as imperial Japanese troops brutalised much of the region.

These days, Manchukuo is a name mostly known to dedicated historians. If it comes up, it is usually in the context of the Qing Emperor Puyi’s humiliating life in the Japanese client state, created after the Japanese invasion of September 1931 and which crumbled in the face of a massive Soviet incursion in August 1945 without putting up much of a struggle. In these stories, Manchukuo is generally thought of as a typical colony. Japan’s wartime pan-Asianist exercise, being a folly and a lie, became totally bankrupt at the end of the war and disappeared into thin air. The Cold War quickly rewrote the geopolitics of the region.

But during its lifetime, the Japanese colony was a highly unusual exercise in the history of imperialism. The harsh realities of Chinese life under the regime existed side-by-side with an ambitious pan-Asian ideological experiment. Japan’s tradition of technocratic modernization played a central role in Manchukuo’s governing bodies, like the Concordia Association, the one-party state’s governing apparatus, and in the so-called South Manchuria Railway Company Research Department, a RAND Corporation-like research institution which ended up running much of Manchukuo’s development.

This interest in technocratic modernization did not remain within established ideological confines; many radical ideas, anything that could inform development, found a receptive audience. For example even socialist ideas and Soviet policies informed the actions of Japanese technocrats and intellectuals, with a number of Japanese Marxists joining Manchukuo’s institutions after fleeing persecution in Japan itself. These Marxist exiles drew up industrial Five-Year Plans and promoted agricultural collectivisation, until they too fell afoul of the army-led purges of the political left in the early 1940s. Under the slogan of “Five Races Under One Union”, pan-Asianists in Manchukuo’s institutions attempted to put their ideas into practice, even finding themselves caught up or participating in movements against Japanese imperialism.

Through this dynamic and open-ended ideological ferment, and its application to practical problems of colonial development, Manchukuo became an experiment in developmental state‐building which had immense consequences for the whole of East Asia. Its intellectual legacy is exemplified by the Japanese “reform bureaucrats” of the 1930s and ‘40s, who saw a technocratic state leading national development—and embracing neither electoral democracy nor class struggle—as being the way forward for East Asia. The Manchurian influence can be found in all the most significant cases of East Asian developmental success.

The Manchurian model of forced industrialisation under single-party rule found post-war expression in China, North Korea, and South Korea during the Park Chung-hee years, directly influenced by people who had participated in the colony’s institutions. The Japanese technocratic planners who worked in Manchukuo likewise returned to serve in the highest levels of government and economic and planning bodies in Japan after the war. They led Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, which governed uninterrupted from 1955 to the 1990s. The most prominent among these was Kishi Nobusuke, once Manchukuo’s economic tsar and among the most ruthlessly anti-Chinese and imperialist of its political leaders, whose postwar position as America’s man in Tokyo allowed him to become Prime Minister from 1957-60 and retain prominence as an elder statesman until the 1980s.

Kenkoku University—the highest academic institution in Manchukuo from 1938 until 1945—was the educational center of the pan-Asianist experiment. Its students came from all over Asia under Japanese rule to learn how to modernize Asia. After the war, they maintained contact with each other while they assumed important roles in East Asia’s postwar order—some of their careers lasting until the 1990s. The legacy of Kenkoku lived on in their political achievements. Across East Asia, alumni implemented their goals of national liberation and state-led industrialization in the region’s postwar states and on all sides of the Cold War divide. By inculcating the region’s rising elites, Manchukuo’s rulers secured an unlikely legacy. While the Japanese empire met its end, its tradition of technocratic state-building endured as East Asia’s new leaders drew on their Japanese training to build its successor regimes.— Ernest Ming-Tak Leung's Articles, The School That Built Asia: Unknown/Students of Kenkoku University, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, August 20, 2021

Over 1,000 applicants for 25 selections: Unprecedented competition rate in recruiting Joseon students to Manchurian University.[24] In the fall of 1937, fierce competition for entrance exams took place. Even the Sino-Japanese War that began in the summer could not quell the heat. The goal was the newly established Kenkoku University in Manchuria. This university, which was to be established in May 1938 in Xinjing (now Changchun), the capital of Manchukuo at the time, was scheduled to select a total of 150 students from six ethnic groups, including Joseon, Japan, Manchuria, Taiwan, Mongolia and Russia. Applications for new students (including Japanese) recruited in Joseon closed on October 20. In Gyeongseong alone, 155 Koreans and 140 Japanese gathered.

The first test for applicants within Joseon was held at Gyeongseong Women's Normal School in Susong-dong for three days starting on December 27. It was unusual that the physical examination was the first. He said : "If you want to work in Manchuria, you must first be physically healthy, so consider your health first" (Entrance Exam Suffering No. 1, Chosun Ilbo, December 28, 1937). Of the 670 applicants, 90 (60 Koreans and 30 Japanese) were selected. The competition rate was 7.4 to 1.

Early the following year, I took the second exam in Gyeongju. Korean test takers were paid full transportation and lodging expenses to and from the test site. He received unprecedented treatment. The second test was an interview. The interview time was divided into three fields: Humanities and social sciences, natural sciences, and general knowledge and personality, and 15 to 20 minutes of interview time was allocated to each field. The final successful candidates were announced in March 1938. Among the applicants from Joseon, only 11 (including 2 Japanese) were successful.

The competition to enter Kenkoku University was fierce the following year. The Government General's Academic Affairs Bureau recommended 83 students for the second entrance exam in 1939. There were 57 Koreans and 26 Japanese. The final number of successful applicants was 13, similar to the previous year. There were 9 Koreans and 4 Japanese (Announcement of successful applicants to Kenkoku University, Chosun Ilbo, January 17, 1939). The characteristic of the second entrance exam was that there were 5 persons from Gyeonggi province. One Japanese person each came from Gwangju, Daegu, Wonsan, and Busan middle schools.

- Free tuition and dormitory fees : Up to 5 wons monthly allowance.

- There are 91 Korean students admitted : 7% of all students.

- The Hwang Min-hwa movement is so severe that it goes to Manchuria.

- Emphasis on military and martial arts training : Participated in the establishment and development of the Korean military after liberation.

- Plan to recruit professors such as Lev Trotsky, Mahatma Gandhi and Pearl Buck.[25]

The university closed on August 7, 1945, when the Kanto-kun were defeaten by Soviet Red Army.[16] Chinese graduates of Kenkoku University were taken to Sibir or met a miserable end during the Cultural Revolution, but Koreans returned to Joseon and adapted well. Some of them contributed to the establishment of universities named after North Korean leaders. Some of them joined the Joseon Political Science Building, the predecessor of what is now Konkuk University. The campus is said to have become the basis for the establishment of Changchun University.

Education

Elites

- Board

- Principal: Ishiwara Kanji

- Assistant principals: Sakata Shoichi (1938—1942), Kamezo Odaka (1942—1945)

- Lecturers

- Masanobu Tsuji

- Kiyoshi Hiraizumi

- Katsuhiko Kakehi

- Kawakami Hajime

- Hu Shih

- Zhou Zuoren

- Choe Nam-seon

- Subhas Chandra Bose

- Mahatma Gandhi

- Pearl S. Buck

- Lev Trotsky

- Saito Takeshi

- Okuda Yasuo

- Sato kiyoji

- Miyagawa Zenzo

- Aiyappan Pillai Madhavan Nair

- Onoue Masao

- Uemura Toshio

- Egashira Tsuneji

- Ishikawa Junjuro

- Shigematsu Nobuhiro

- Hwang Do-yeon

- Masajiro Takigawa

- Masao Fukushima

- Tobari Chikufu

- Inaba Kunzan

- [...]

Curriculum

According to the important research article by PhD. Ernest Ming-tak Leung from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, the key elements that make up the legacy of Kenkoku University are the Japanese Marxists who were expelled from their homeland after 1930. It was they who, through their teachings in Kenkoku, promoted an ideology that was not welcome in their homeland. This work accidentally created a notable contemporary socio-political phenomenon, that is the Manchukuo Marxism. Yuka Hiruma-Kishida reported more clearly that, for the first time in the world history, in a place that few people pay attention to (and even despise) like Manchuria, the combination of ancient East Asian political thought was planted with completely new social liberalization trends.

The conservative Kenkoku persons favored Mencius' ōdō ideology (王道樂土思想,[26] "kingly way" or "way of right"), while the younger group belonged to the marxist movement, eventually "making peace" with a new ideology, called as Panasianism or simply "Mingoku Kyōwa Shisō" (民國協和思想, "republican ideology" or "people and country become one"). In fact what happened during the Cold War and in the years that followed proved that Asian society essentially followed this form of ideology. It is both very seriously traditional and not out of step with ideologies originating from the Western world.

Kendai was the only institution of higher learning administered directly by the Manchukuo's governing authority, the State Council, which was dominated by Japanese officers. Kendai recruited male students of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, Mongolian, and Russian backgrounds, and aimed to nurture a generation of leaders who would actualize the Pan-Asianist goal of "harmony among various peoples residing in Manchukuo", one of the founding principles of Manchukuo. Wartime relations between Japanese and non-Japanese are often framed in terms of binary narratives of resistance to or collaboration with Japanese imperialism. Assuming that national consciousness had firmly taken root in people's minds, most historians simply dismiss Japan's wartime discourse of Pan-Asianism as just another empty rationale for the domination of subject peoples by an imperial power, akin to the Anglo-American ‘white man's burden’. Recent scholarship, however, has complicated the picture by identifying multiple and competing articulations of Pan-Asianism, while re-examining its effects on policy making and its reception by subject populations. My dissertation extends this effort by investigating actual practices of Pan-Asianism as experienced by Japanese and Asian students enrolled at a unique institution whose ideal was Asian unity on the basis of equality. Taking Kendai as a case study and uncovering the interactions that shaped relations below the level of the state, I attempt to demonstrate that the idealistic and egalitarian version of Pan-Asianism exercised considerable appeal even late into World War II.

— PhD. Yuka Hiruma-Kishida, Kenkoku University, 1938-1945: Interrogating the praxis of Pan-Asianist ideology in Japanese occupied Manchuria, University of Iowa, Autumn 2013, DOI: 10.17077/etd.9ocg-ifd7

Influences

During the Cold War era, former professors and students of Kenkoku University made great contributions to the evolution of the whole East Asia region. However, at this time, because of the complicated political situation, they hardly had any official contact.

After the Cultural Revolution in China proper ended, a delegation of many Chinese alumni under the "support" (擁護) of Jiang Zemin went to Tokyo to connect with Japanese alumni. This event not only helped People's Republic of China receive huge aid from Japan to promote economic reform, but also opened a whole new chapter for Kenkoku University alumni.

In 1989, the Manchurian Studies Association or Kenkoku-Daigaku Alumni Association (建國大學同志會, Jianguo Daxue Tongzhi Hui, Kenkoku Daigaku Doshi Gai) with a core of Chinese and Japanese alumni was established. This is both a friendship organization and also a force to expand the influence of Asia's largest economies. However, from then until 2023, this organization only operates in the field of economic and sometimes cultural cooperation, not allowed to attend any political or military events.

The most important event for the Alumni Association was supporting the establishment of Changchun University. Initially, the name chosen was "construction" (建設, Jianshe, Kensetsu), but because the Chinese government considered it "politically sensitive", that idea failed.

Stamp of Kenkoku Shrine, 1942

Stamp of Kenkoku Shrine, 1942 On August 23, 1964, Zhou Peiyuan (middle) accompanied Mao Zedong (left) to meet with Sakata Shoichi (right), as the head of the Japanese delegation

On August 23, 1964, Zhou Peiyuan (middle) accompanied Mao Zedong (left) to meet with Sakata Shoichi (right), as the head of the Japanese delegation 1984 Yan'an Street, Changchun City

1984 Yan'an Street, Changchun City Site of Ministry of Culture and Education Development of Manchukuo. Original building demolished. Now Primary School Attached to Northeast Normal University

Site of Ministry of Culture and Education Development of Manchukuo. Original building demolished. Now Primary School Attached to Northeast Normal University Library of Xinjing Branch of South Manchurian Railway Co

Library of Xinjing Branch of South Manchurian Railway Co

In the decades after World War II, in general and basically, the legacies of Kenkoku University were completely forgotten due to overlapping conflicts in a turbulent Asia. There is a paradox that, although the students of this academy participated in all the important political forces of the region and even accidentally became enemies of each other, no one mentioned their "master" (Japanese: 祖師). This connection only began to be revived by scholars in the late 2010s, when the last generation of students was old and all political conflicts were no longer there.

November 15, 2020, TV Asahi aired a documentary titled Telementary 2020 - Vanished University - Manchuria's Phantom Dream (Japanese: テレメンタリー2020「消えた大学 幻の満州の夢」).[27][28] From the reporter, whose deceased grandfather was a graduate of Kenkoku University, was trying to uncover more information about it. The film immediately won the public's sympathy, with some netizens even saying that it not only restores a heroic period of history that the Japanese have tried to bury for many years, but also restores people's confidence many individuals to overcome the Covid-19 pandemic. Even in Vietnam, a country with very little connection to what happened in Manchuria decades earlier, Kenkoku University and its legacy have become a hot topic of debate on youth forums.

See also

References

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, New York, pp. 282, ISBN 0-521-66991-X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Svoboda-1965-172

- ↑ The Japan Annual of Law and Politics, Volume 1 Science Council of Japan. 1956. Retrieved: 04/05/18

- 1 2 3 The Living Age Vol 350. Littell, E & R,S, Littell. 1936

- ↑ British documents on foreign affairs - Japan, January 1928-December 1929 Bourne, K & A, Trotter. 1991. pp48-49. Retrieved: 04/05/18

- ↑ "Milestones: 1921–1936 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica article on Manchukuo Archived 21 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Young, Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism.

- ↑ Culver, Margaret S. "Manchuria: Japan's Supply Base." Far Eastern Survey, vol. 14, no. 12, 1945, pp. 160–163.

- ↑ Westad, Odd Arne (2012). Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750. Basic Books. p. 252. ISBN 978-0465056675.

- ↑ Walker, Michael (2017). The 1929 Sino-Soviet War: The War Nobody Knew. Modern War Studies. ISBN 978-0700623754.

- ↑ Meyer, Michael (February 9, 2016). In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1620402887.

- ↑ Simkin, John (February 5, 2007). "Sterling and Peggy Seagrave: Gold Warriors". The Education Forum. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

Americans think of WW2 in Asia as having begun with Pearl Harbor, the British with the fall of Singapore, and so forth. The Chinese would correct this by identifying the Marco Polo Bridge incident as the start, or the Japanese seizure of Manchuria earlier.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback)

- ↑ Yuan, Zheng. "Local Government Schools in Sung China: A Reassessment," History of Education Quarterly (Volume 34, Number 2; Summer 1994): 193–213

- 1 2 Kevin Doak (2007). A History of Nationalism in Modern Japan: Placing the People. BRILL. p. 241. ISBN 978-90-04-15598-5.

- ↑ David H. Price (May 19, 2008). Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War. Duke University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8223-8912-5.

- ↑ Hiruma Kishida, Yuka (2019). Kenkoku University and the Experience of Pan-Asianism. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350057869.

- ↑ Tatsuhiko, Yoshizawa. "The Manchurian Incident, the League of Nations and the Origins of the Pacific War. What the Geneva archives reveal". Japan Focus. Asia-Pacific Journal. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ テレメンタリー2020「消えた大学 幻の満州の夢」 2020年11月15日(日) 4:30 ~ 5:00

- ↑ Leung, Ernest Ming-tak (August 20, 2021). "The School That Built Asia". Palladium. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ↑ Stevens, John (1999). Invincible Warrior: A Pictorial Biography of Morihe Ueshiba, the Founder of Aikido. Boston, London: Shambhala. p. 63. ISBN 9781570623943.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley. "Interview with Shigenobu Tomura". Aiki Journal. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ Chosun Ilbo, October 22, 1937: 25명 선발에 지원자가 천여명’ ‘만주 建大 조선학생 모집에 전대미문의 경쟁률.

- ↑ Modern Gyeongseong: Kenkoku University in Manchuria, an escape route for Joseon's elite youth ?

- ↑ Yi Jung-hee, Education of Kenkoku University in Manchukuo and Korean Student, Journal of Manchurian Studies, The Manchurian Studies Association, Seoul, ROK, 2016, (22), pp.225-255

- ↑ 消えた大学 幻の満州の夢「五族協和」を理想に集ったエリートたち 【戦争証言】

- ↑ 満州にあった「建国大学」とは...“幻の大学”に出身学生の孫が迫る

Bibliography

- English

- Smith, Lloyd (January 1940). Everybody's Complete Encyclopedia. Whitman Publishing Company. Racine, Wisconsin. p. 462

- Clauss, Errol MacGregor. "The Roosevelt Administration and Manchukuo, 1933–1941", Historian (1970), 32#4 pp 595–611.

- Fleming, Peter, Travel's in Tartary: One's Company and News from Tartary: 1941 (Part one: Manchukuo)

- "Sun Yat-Sen's Idea of Regionalism and His Legacy". Sun Yat-Sen, Nanyang and the 1911 Revolution. 2011. pp. 44–60. doi:10.1355/9789814345477-007. ISBN 9789814345477.

- Wong, P., Manvi, M., & Wong, T. H. (1995). Asiacentrism and Asian American Studies? Amerasia Journal, 21(1/2), 137–147.

- Starrs, Roy (2001) Asian Nationalism in an Age of Globalization. London: RoutledgeCurzon ISBN 1-903350-03-4.

- Review in The Journal of Japanese Studies 34.1 (2007) 109–114 online

- Mitter, Rana. The Manchurian Myth: Nationalism, Resistance, and Collaboration in Modern China (2000)

- Kamal, Niraj (2002) Arise Asia: Respond to White Peril. New Delhi: Wordsmith ISBN 81-87412-08-9.

- Starrs, Roy (2002) Nations under Siege: Globalization and Nationalism in Asia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 0-312-29410-7.

- Duara, Prasenjit. Sovereignty and Authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian Modern (2004)

- Elliott, Mark C (2003). "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies". Journal of Asian Studies. 59 (3): 603–646. doi:10.2307/2658945. JSTOR 2658945. S2CID 162684575.

- Yamamuro, Shin'ichi. Manchuria under Japanese Dominion (U. of Pennsylvania Press, 2006)

- Saaler, Sven and J. Victor Koschmann, eds., Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Colonialism, Regionalism and Borders. London and New York: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0-415-37216-X

- Reginald Fleming Johnston. "Twilight in the Forbidden City". Soul Care Publishing, 18 March 2008. ISBN 978-0-9680459-5-4.

- Mahbubani, K. (2008). The new Asian hemisphere: The irresistible shift of global power to the East. PublicAffairs.

- Toshihiko Kishi. "Manchuria's Visual Media Empire (Manshukoku no Visual Media): Posters, Pictorial Post Cards, Postal Stamps", Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 10 June 2010. ISBN 978-4-642-08036-1

- Saaler, Sven and C.W.A. Szpilman, eds., Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History, Rowman & Littlefield, 2011. two volumes (1850–1920, 1920–present).ISBN 978-1-4422-0596-3 (vol. 1), ISBN 978-1-4422-0599-4 (vol. 2)

- Toshihiko Kishi, Mitsuhiro MATSUSHIGE and MATSUMURA Fuminori MATSUMURA, eds, 20 Seiki Manshu Rekishi Jiten [Encyclopedia of 20th Century Manchuria History], Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2012, ISBN 978-4642014694

- Aaron Stephen Moore, The Yalu River Era of Developing Asia: Japanese Expertise, Colonial Power, and the Construction of Sup'ung Dam, The Journal of Asian Studies, Duke University Press, February 2013.

- Miike, Y. (2014). The Asiacentric turn in Asian communication studies: Shifting paradigms and changing perspectives. In M. K. Asante, Y. Miike, & J. Yin (Eds.), The global intercultural communication reader (2nd ed., pp. 111–133). Routledge.

- Szpilman, Christopher W. A. (2017). "Japan and Asia". In Saaler, Sven (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History. pp. 25–46. doi:10.4324/9781315746678-3. ISBN 978-1-315-74667-8.

- Yuka Hiruma-Kishida (author) & Christopher Gerteis (series editor), Kenkoku University and the Experience of Pan-Asianism: Education in the Japanese Empire (SOAS Studies in Modern and Contemporary Japan), SOAS Studies in Modern and Contemporary Japan, Bloomsbury Academic, London, England, United Kingdom, October 3, 2019. ISBN 1350057851, ISBN 978-1350057852.

- Khanna, P. (2019). The future is Asian: Commerce, conflict, and culture in the 21st century. Simon & Schuster.

- Yin, J. (2022). Rethinking Eurocentric visions in feminist communication research: Asiacentric womanism as a theoretical framework. In Y. Miike & J. Yin (Eds.), The handbook of global interventions in communication theory (pp. 188–214). Routledge.

- Miike, Y. (2022). An anatomy of Eurocentrism in communication scholarship: The role of Asiacentricity in de-Westernizing theory and research. In W. Dissanayake (Ed.), Communication theory: The Asian perspective (2nd ed., pp. 255-278). Asian Media Information and Communication Center.

- Japanese

- 志々田文明 (1993). "建国大学の教育と石原莞爾". 人間科学研究. 早稲田大学人間科学学術院. 6 (1): 109–123. hdl:2065/3873. ISSN 0916-0396.

- 湯治万蔵 (1981). 建國大學年表 (非売品 ed.). 建国大学同窓会建大史編纂委員会. p. 570. doi:10.11501/12115666. JPNO 82029900. 昭和11年の建大創設構想に基く初動から昭和20年の閉学に至るまでの経過が日付を追って詳細に記録されている。非売品。

- 建国大学同窓会編『歓喜嶺 遥か』(文集)1991年6月刊、B5判、(上)401頁、(下)427頁。教員、学生の執筆260編。非売品。

- 三浦英之 (2015). 五色の虹 : 満州建国大学卒業生たちの戦後. 集英社. ISBN 9784087815979. JPNO 22683496.

- 宮沢恵理子『建国大学と民族協和』風間書房、1997年。ISBN 4759910158

- 三浦英之『五色の虹 満州建国大学卒業生たちの戦後』、2015年。ISBN 978-4087815979。

- 山根幸夫『建国大学の研究―日本帝国主義の一断面』 汲古書院、2003年。ISBN 4762925489

- 志々田文明『武道の教育力―満洲国・建国大学における武道教育―』日本図書センター、2005年。 ISBN 4820593161

- 志々田文明 早稲田大学人間科学研究による論文 建国大学の教育と石原莞爾 (PDF)

- 小野寺永幸『歓喜嶺遥か、北帰行-満州建国大学と旅順高校の異材』(北の杜編集工房、2004年)

- 鈴木登志正『歓喜嶺遥か!満州建国大学植樹班物語-東西文化研究、第1号~第4号』(東西文化研究会、1999年)

- Korean

- ‘만주 건국대학’이라는 실험과 육당 최남선 (Choe Nam-seon and Kenkoku University as a Testing Ground for ‘Concord of Nationalities’ in Manchukuo), 사회와역사(구 한국사회사학회논문집), 2016, vol., no.110, pp. 309-352 (44 pages), UCI : G704-000024.2016..110.011, 발행기관 : 한국사회사학회, 연구분야 : 사회과학 > 사회학

- Russian

- Лестев А.Е. Использование социально-утопических идей в японской континентальной политике в Маньчжоу-го и Монголии // Россия - Китай: история и культура: сборник статей и докладов участников XI Международной научно-практической конференции. – Казань: Изд-во Академии наук РТ, 2018. С. 200-206.

- Vietnamese

- Lý Đông A, Ký trình: Ngày giờ đã khẩn cấp!, Liuzhou, Guangxi, China, 1943.

- Lý Đông A, Tuyên ngôn ngày thành lập Việt Duy Dân Đảng, Hoa-Binh, Tonkin, Indochina, 1943.

- Masaya Shiraishi (author) & Ngô Bắc (translator), Việt Nam Kiến Quốc Quân và cuộc khởi nghĩa năm 1940 (Nation-Building Army of Viet-Nam and the 1940 Revolt), December 21, 2009.

- Ernest Ming-tak Leung (author) & Ngọc Giao (translator), Trường đại-học kiến-thiết tương-lai Á-châu (The school that built Asia), Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022.

External links

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere at Britannica

- Foreign Office Files for Japan and the Far East

- WW2DB: Greater East Asia Conference

- All about the Asiacentricity

- An Anatomy of Eurocentrism in Communication Scholarship: The Role of Asiacentricity in De-Westernizing Theory and Research

- The Asiacentric Idea in Communication: Understanding the Significance of a Paradigm

- Asian Communication Studies at the Crossroads: A View to the Future from an Asiacentric Framework

- Toward an Alternative Metatheory of Human Communication: An Asiacentric Vision

- Theorizing Culture and Communication in the Asian Context: An Assumptive Foundation

- Zionism and the Japanese East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

- Japanese references to Mantetsu Railway Company

.jpg.webp)