| Kennicott Bible | |

|---|---|

| Bodleian Library, MS. Kennicott 1 | |

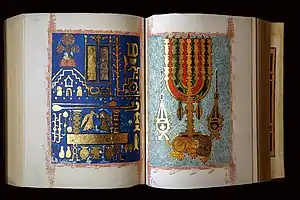

Two fully illustrated pages of the Kennicott Bible (facsimile edition) | |

| Also known as | First Kennicott Bible |

| Type | Codex |

| Date | 24 July 1476 |

| Place of origin | A Coruña |

| Language(s) | Hebrew |

| Scribe(s) | Moses ibn Zabarah |

| Illuminated by | Joseph ibn Hayyim |

| Patron | Isaac de Braga |

| Material | Vellum |

| Size | 30 cm × 23.5 cm |

| Script | Sephardic |

| Contents | Hebrew Bible, Sefer Mikhlol by David Kimhi |

| Previously kept | Radcliffe Library |

| Discovered | Acquired by Patrick Chalmers in Gibraltar in the 18th century |

The Kennicott Bible (Galician: Biblia Kennicott or Biblia de Kennicott), also known as the First Kennicott Bible,[1] is an illuminated manuscript created in the city of A Coruña in 1476.[2] Written by the calligrapher Moses ibn Zabarah and illuminated by Joseph ibn Hayyim, this manuscript is considered by some, such as the historian Carlos Barros Guimeráns, the most important religious manuscript of medieval Galicia.[3] It is also regarded as one of the most exquisite illuminated manuscripts in Hebrew language in an article published by the Library of the University of Santiago de Compostela,[2] and the most lavishly illuminated Sephardic manuscript of the 15th century by Katrin Kogman-Appel.[4]

The manuscript is named after Benjamin Kennicott, a Hebrew scholar and canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, who bought the manuscript from the Radcliffe Library, from where it was transferred to the Bodleian Library in 1872.[5][6]

According to the Jewish historian Cecil Roth, one of the most outstanding aspects of this copy is the close collaboration it shows between the calligrapher and the illuminator, something rarely achieved in this type of work.[7]

Background

It is not known exactly when Jewish people arrived and settled in A Coruña, but the first documentation of the Jewish presence dates to 1375. Jewish population in A Coruña grew rapidly throughout the Late Middle Ages. It is thought that after the persecution of Jews in Castile, a large number of Jewish people took refuge in Galicia, and particularly in the "Herculean city" (i.e. A Coruña). The Jewish community in A Coruña traded with Castile and Aragon, and in 1451 they contributed to the rescue of the Murcian Jews with a large sum of money, which could demonstrate the prosperity of the community.[8]

The Kennicott Bible was created in A Coruña in 1476, shortly before the expulsion of Jews from Spain. At the time, A Coruña had a prosperous Jewish community which, according to Cecil Roth, was one of the richest Jewish communities on the Iberian Peninsula, owning several Bibles in Hebrew, amongst which he cites the Cervera Bible. In addition to economic prosperity, the Herculean Jewish community had a relevant cultural activity, highlighting the largest school of Jewish illuminators in Europe,[9] amongst which Abraham ben Judah ibn Hayyim stood out in the mid-15th century, who was considered the continent's most distinguished master in the art of mixing colours to illuminate manuscripts and who made one of the most used books in Europe at the end of the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Renaissance.[10] The fame of A Coruña illuminators is evident in Roth's book The Jews in the Renaissance, in which he cites the most important known Jewish artists from Europe:[11]

Unfortunately, this work remained generally anonymous in Italy. We know of some splendidly gifted Spanish illuminators of the time (such as Joseph ibn Hayyim, who was responsible for the famous Kennicott Bible in Oxford) and some extremely capable Germans (such as Joel ben Simeon, author of several beautiful codices of the Passover ritual, or Haggadah).

Despite this, the existence of a previous tradition regarding the illumination of Hebrew texts in Galicia is not known, so the Kennicott Bible cannot be attributed to a specific school, but according to Kogman-Appel it is an isolated phenomenon.[4]

Not long after the creation of the Kennicott Bible, in 1492, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) issued the Alhambra Decree in Granada, which forced those who professed the Jewish religion to leave the kingdom or convert to Catholicism. This fact caused the exile of many Jewish families, when history lost track of them, as in the case of the Hayyim family, whose surname appears in different parts of Europe, in Turkey and in Palestine. Although it is unknown whether they were descendants of the A Coruña illuminators, or if they died in A Coruña, or left Spain.[12]

History

In 1476, Isaac, a Jewish silversmith from A Coruña, son of Salomón de Braga, commissioned an illuminated Bible from the scribe Moses ibn Zabarah,[13] who lived in A Coruña with his family on behalf of his patron. He spent ten months to scribe the Bible, writing two folios on a daily basis.[14] On the other hand, the responsibility of illuminating the manuscript fell on Joseph ibn Hayyim, whose name has been remembered thanks to this work.[15] According to Cecil Roth, the commission may had been motivated by the presence of Cervera Bible in A Coruña, which was owned by the Mordechai Jewish family at least since 1375. British historian suggested:[16][3]

In the second half of the 15th century, Isaac, son of Don Salomón de Braga, would have seen [the Cervera Bible] and coveted it. Being unable to acquire it, he would have commissioned another codex with even richer illustrations and following the same guidelines, from two exceptionally competent artists.

The presence of the Cervera Bible (created in Cervera, Catalonia) in A Coruña is attested by the birth record of Samuel, son of Mordechai, on folio 450v. Another birth record, of Judah ibn Mordechai, on folio 451v, seems to belong to the same family. It cannot be assured that the Cervera Bible remained in the city when Isaac commissioned the Kennicott Bible, but it seems possible that it still remained in A Coruña 37 years later, when Isaac de Braga could have seen it and commissioned a similar copy.[16]

The exact date and place of origin of the Kennicott Bible and the identity of the persons who had it done are attested in a long colophon on folio 438r, which states that the work was finished "in the city of A Coruña, in the province of Galicia in northwestern Spain, on Wednesday the third day of the month of Ab in the year 5236 of Creation" (i.e. 24 July 1476), and claims to be solely responsible for the complete text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible: he copied it, added the vocalization notes, wrote all the masorah notes and compared and corrected the text with an exact copy of the Bible. Ibn Zabarah also declares in the colophon that he wrote it for the "admirable young Isaac, son of the late, honourable and beloved Don Salomón de Braga (may his soul rest in peace in the Garden of Eden)".[5]

The Alhambra Decree issued by Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1492 prompted Isaac de Braga as well as many other Jewish families to leave Spain.[17] For the protection of the manuscript, Isaac commissioned a Bible box that could be locked with a key, bearing the name of Yzahak in Hebrew. This is the last time the manuscript being mentioned while it was still in Jewish hands.[16] The last thing known of its owner, the "admirable youth" Don Isaac, is that he left A Coruña in 1493 by sea with the help of shipowners and royal officers, taking along with the manuscript about 2,500,000 maravedís.[18] A possible route can be traced from A Coruña to Portugal, and from there to North Africa, and then to Gibraltar, where, almost three centuries later, it would be acquired by Patrick Chalmers, a Scottish merchant; and eventually, the manuscript found its way to Oxford.[19]

The next known record of the manuscript dates to June 1770, when Benjamin Kennicott, an Anglican clergyman, Hebrew scholar, and librarian of Oxford's Radcliffe Library, told the library trustees that "it might add considerably to the Ornament of that Library, if it possessed one manuscript of the Hebrew Bible"; and informed them that he had in his hands such a manuscript, "very elegant and finely illuminated", and that it was for sale. The manuscript had come into Kennicott's hands through the Earl of Panmure, to whom it had been entrusted by the aforementioned Scottish merchant Patrick Chalmers.[19] It is recorded in a minutes book of the Radcliffe trustees that they "bought a Hebrew manuscript of the Old Testament on 5 April 1771, from Chalmers".[5] The manuscript remained at Radcliffe Library for just over a century. It was transferred to the Bodleian Library in 1872,[19] where it was catalogued under the name of Kennicott in honour of the Christ Church Cathedral canon who had discovered it 100 years earlier to make use of its Hebrew text.[20]

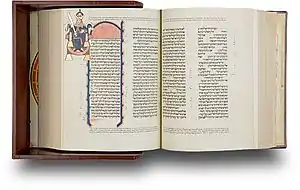

Initially, the manuscript was not given much importance, as Jewish art was not considered worth studying at the time. Nevertheless, it came to be considered a gem of Jewish art after Rachel Wischnitzer published a work in Berlin in 1923 featuring one of the manuscript's folios on the cover.[5] Since then, the Kennicott Bible became a subject of analysis, with a detailed description published in 1982, co-written by Bezalel Narkiss, Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, and Victor Tcherikover.[4] Narkiss was one of the leading scholars of the Kennicott Bible, who together with Cohen-Mushlin, made an introduction to the 1985 facsimile edition of the manuscript, which was produced under his supervision.[21][22] To facilitate access to the manuscript, the Centro de Información Xudía de Galicia in Ribadavia has enabled a digital system for visitors to browse through its pages.[23]

Since 2015, the Comunidade Xudía Bnei Israel de Galiza, on behalf of the Galician Jewish community, has demanded the return of the original manuscript to A Coruña. A Coruña has a facsimile copy that was acquired by the Xunta de Galicia and is on display at the Real Academia Galega de Belas Artes. The Comunidade Xudía Bnei Israel defended the return of the manuscript to the city based on moral and historical justice and the historical value that the Bible has for the city.[24] The Asociación Galega de Amizade con Israel also urged the Xunta de Galicia to retrieve the manuscript and take it back to Galicia.[25]

In November 2019, after 527 peripatetic years, the Kennicott Bible went back to Galicia, its place of birth, for the first time. The manuscript was loaned to the regional government of Galicia (Xunta de Galicia),[26] and on display in the exhibition Galicia: A Story in the World at the Museo Centro Gaiás in Santiago de Compostela.[27] Román Rodríguez González, minister for culture and tourism in the regional government, said the region had no plans to ask for the manuscript's permanent return.[26]

Characteristics

General characteristics and calligraphy

The Kennicott Bible contains the five books of the Torah (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), the books of the Prophets and Hagiographers, as well as the grammatical treatise Sefer Mikhlol by Rabbi David Kimhi (also known by his Hebrew acronym RaDaK רד"ק —Rabino David Kimhi—), which was copied from the Cervera Bible.[25][28][29] The original copy is bound in brown goatskin with geometric interlacing decoration, and was protected by a wooden box.[30]

The Bible is mostly written in two columns of 30 lines each. Ibn Zabarah graced the manuscript with Sephardic cursive written in brown ink on folios measuring 30 centimetres (12 in) by 23.5 centimetres (9.3 in).[30][3] During the creation of the work there was a close collaboration between scribe and illuminator, perceptible when examining in detail the relationship between the text and the illuminations. This collaboration can also be seen in the decorations made by Ibn Hayyim in the margins and in the space between the columns, where such special blank spaces were not required.[16]

According to Carlos Barros, the Kennicott Bible is "distinguished by the outstanding interpenetration between the scribe (Moses ibn Zabarah) and the illuminator (Joseph ibn Hayyim), a fact that can be appreciated in the 'mutual gifts' for each other: Moses emphasized the events concerning Joseph, son of Jacob, while Joseph decorated Psalm 90 (prayer of Moses) with particular finesse." The quality of the manuscript did not go unnoticed by the contemporaries of Moses ibn Zabarah, who spoke highly of the work that "it was not made by a man, but by the Angel of God, a perfect sage, pious and holy".[3]

The volume is preserved in a leather case that could have been made by the scribe himself, as can be deduced from a cryptic phrase that appears in the colophon.[20]

Illumination

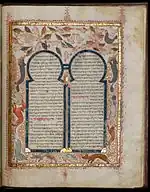

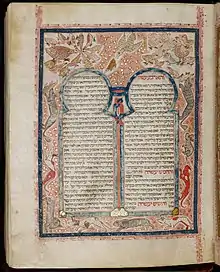

The manuscript was conceived as a work of art by Ibn Zabarah, that is the reason he hired Joseph ibn Hayyim, then the best European illuminator along with the German Jew Joel ben Simeon.[3][28] The original manuscript, made on high-quality parchment,[20] consists of 922 pages measuring 30 cm by 23.5 cm, of which 238 are illuminated in vivid colours and silver foil, with images rich in both detail and symbolism, making the manuscript a work of art unique with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery, as well as emphasizing highly stylized and even abstract figures,[28] giving these miniatures an ornamental effect that increases with an ingenious background composed of a marginal border of red, blue and green arabesques, with occasional gold details.[31] A grammar compendium for students learning writing is laid out on the first 15 and the last 12 folios decorated with full-page illuminations. Most of the texts are set in architectural niches with illustrations having no relation to the texts. Sometimes the niches condition the extension of the texts, which may indicate that the former were made before the latter. The most ingenious ornaments are found in the Pentateuch, located at the beginning of each of the 54 parashiyot or sections into which the weekly reading of this volume is divided. According to Cecil Roth, in the Kennicott Bible ornament predominates over illustration, representing the triumph of conventionalism over convictions, and he points out that:[31]

... [Joseph ibn Hayyim] usually prefers to use decorative elements — drawings of intricate interweaving, in which he follows a secular tradition that goes back to the beginning of the Middle Ages, grotesques, dragons, and mythological beasts, and many other things in the style. He has a great ability to represent animals, especially birds, in which he also shows a great love for them. There are also a number of things of great entertainment, such as the festive bear playing a bagpipe, or the attack by armed cats on a castle defended by mice. There is generally very little Jewish flavour in this work, which is an entirely individual mixture of Gothic, Renaissance, and Moorish elements, especially notable for richness of imagery and meticulous execution.

Gerardo Boto Varela, however, attributes this conventionalism to the "low demands" of Isaac de Braga and the "limited talent" of Joseph ibn Hayyim:[32]

There is no interest in representing with a certain conviction and yes with convention, perhaps because Isaac de Braga was not a particularly meticulous client nor Joseph ibn Hayyim a miniaturist of great skill. Its zoological and theriomorphic repertoire is the result of the adaptation of early medieval rooting formulas to the grotesque mood of the late centuries.

The manuscript's drawings combine Christian, Islamic, and folk motifs. It has 24 canonical book headings, 49 parashiyot, 27 pages of profusely illuminated arcaded forms framing the text of the grammatical treatise Sefer Mikhlol, 9 carpet pages, and 150 psalm headings.[33] There is frequent use of zoomorphic letters, an old tradition that had been developed in Merovingian scriptoria at the end of the 8th century, that reappears in this manuscript.[32] The decoration is based on a wide variety of models from the past, including the Cervera Bible. Another characteristic feature of the Kennicott Bible, which it also shares with the Cervera Bible, is the inclusion of narrative and figurative illustrations. In this way, the two illuminators broke with the anti-figurative tradition of Sephardic Bibles.[4]

In general, the art of the manuscript is profoundly Mudéjar that draws from the Spanish Plateresque style, which is especially evident in the arches separated by a single column that frame the text of Sefer Mikhlol. Each bifora is different after an original model of Spanish Mudéjar art.[34] However, Sephardic tradition is not the only influence. Sheila Edmunds found connections of the manuscript's zoomorphic motifs with Central European playing card illustrations, specifically those produced during the 15th century in the territories of present-day Germany and the Netherlands, which were very popular and had a considerable influence on manuscript illumination. Edmunds especially notes the presence of these elements in the decoration of the Sefer Mikhlol text and in the elaboration of parashiyot or sections of biblical books. According to Edmunds, Ibn Hayyim had access to the German models through commercial contacts that existed between Germany and the Jewish community of A Coruña, or the patron who commissioned the manuscript.[35]

As far as colour is concerned, Emilio González López highlights the richness of its brilliance as a characteristic of "A Coruña school" of illumination. Roth emphasizes the profusion of gold, and to a lesser extent, silver in the margins, composed with great skill that, according to the author, "almost give the impression of being enamel", without turning into ostentatiousness or vulgarity thanks to the artist's balanced taste, making the manuscript, in Roth's words, "a coherent work of art from beginning to end."[7]

Regarding the illumination of the manuscript, it is worth noticing what Roth pointed out:[12]

The illumination, in the full meaning of the word, of Hebrew manuscripts may surprise those who remember how the severe prohibition against making any "engraved image" was interpreted at certain stages of Jewish history. However, in the Middle Ages, the prohibition was not always enforced, and some Hebrew codices of this time—mostly of German and Italian origin—are sumptuously illustrated in the fashion of the ordinary manuscripts of that time. But in Spain, the Muslim iconoclastic tradition had for a long time a strong influence on both the Arabs and the Jews. This is the reason for the tendency of the Spanish Hebrew manuscripts to be rather embellished than illuminated with respect to the subject (as are the non-Jewish codices). And even more, the illuminated pages are often placed at the beginning or at the end of the volume, separated from the actual text, which is inviolable. This is the case of the Kennicott Codex, in which the main illuminated folios are the first fifteen and the twelve that come after the Bible. However, the authors did not radically depart from the Arab iconoclastic tradition, but sought a moderate position between Muslim iconoclasm and Christian Renaissance that favoured figurative representation.

The Kennicott Bible is, according to Kogman-Appel, a unique example in the context of 15th-century biblical decoration, characterized by modest style, few innovations, and a frequent return to past decorative traditions.[36]

Colophon

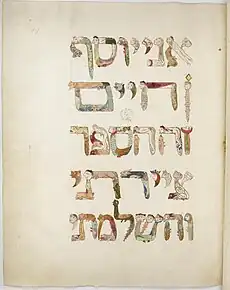

A notable aspect of the Kennicott Bible is found in its colophon. Most of such colophons provide information about scribes and sometimes vocalizers, but rarely mention illuminators. The Kennicott Codex is one of the few exceptions, as a whole page is dedicated to the artist, whose name appears written in large anthropomorphic and zoomorphic letters.[37]

According to Carlos Barros, it was the illuminator himself who put his own signature with huge letters representing figures of naked men and women, animals and fantastic beings on an entire page that say: "I, Joseph ibn Hayyim, have illuminated and completed this book."[3]

The colophon also sheds light on the identity of the scribe (Moses ibn Zabarah) who made the copy and the exact date and place of completion of the Bible (24 July 1476 in the city of A Coruña), as well as the identity of who commissioned the work (Isaac de Braga, son of Salomón de Braga).[5]

See also

- Jewish Bibles and manuscripts created in Spain

- Other related topics

References

- ↑ Gerli 2003, p. 115.

- 1 2 Fonseca (8 June 2015). "O facsímile da Biblia de Kennicott na BUSC". busc.wordpress.com (in Galician). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Barros, Carlos (2007). "A Biblia Kennicott: Unha biblia xudía na Galicia do século XV". agai-galicia-israel.blogspot.com (in Galician). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Kogman-Appel 2004, p. 212.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Antonio Rubio 2006, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Trullo, José Luis, ed. (2014). "La Biblia de Kennicott y la importancia de la tradición hebrea en España". biblias.com.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 González López 1967, p. 201.

- ↑ "A Coruña". sefardies.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ González López, E. (1987). "La escuela de iluminadores hebreos en La Coruña. Su labor: La Biblia Kennicott iluminada y en hebreo". La Coruña: Paraíso del Turismo (in Spanish). A Coruña: Venus Artes Gráficas.

- ↑ González López 1967, p. 197.

- ↑ Roth 1959, p. 207.

- 1 2 González López 1967, p. 199.

- ↑ "Braga, Salomón de". sefardies.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ "Zabarah, Moisés ibn". sefardies.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ Metzger, Thérèse (1998). "Joseph ibn Hayyim - illuminator". oxfordindex.oup.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Antonio Rubio 2006, p. 222.

- ↑ "The Edict of Expulsion of the Jews". sephardicstudies.org. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ "Isaac". sefardies.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 "The Kennicott Bible". bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 González López 1967, p. 198.

- ↑ Barral Rivadulla, Dolores (1998). La Coruña en los siglos XIII al XV: Historia y configuración urbana de una villa de realengo en la Galicia medieval (in Spanish). A Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. p. 72. ISBN 9788489748170.

- ↑ "The Kennicott Bible (Facsimile Edition, 1985)". catalog.princeton.edu. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ "Biblia Kennicot". redjuderias.org (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ García, Rodri (4 June 2015). "Los judíos quieren recuperar la «Biblia de Kennicott»". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). A Coruña. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 "A Biblia xudía da Coruña, o grande patrimonio esquecido". Vieiros (in Galician). 7 August 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 Jones, Sam (2 November 2019). "500 years after the expulsion of Spain's Jews, medieval Bible comes home". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ↑ "Galicia: a story in the world: some outstanding pieces". cidadedacultura.gal. 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Un perdido tesoro coruñés". La Opinión A Coruña (in Spanish). A Coruña. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ "The Kennicott Bible". library.duke.edu. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- 1 2 Antonio Rubio, María Gloria de (2016). "Biblia Kennicott". In Villares, Ramón (ed.). Galicia Cen: Obxectos para contar unha cultura (in Galician). Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega. p. 121. ISBN 9788492923724.

- 1 2 González López 1967, p. 200.

- 1 2 Boto 2007, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ "The Kennicott Bible, the Most Lavishly Illuminated Hebrew Bible to Survive from Medieval Spain". historyofinformation.com. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ González López 1967, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Kogman-Appel 2004, p. 213.

- ↑ Kogman-Appel 2004, p. 214.

- ↑ "15th Century: The Kennicott Bible". library.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

Bibliography

- Antonio Rubio, Mª Gloria de (2006). Instituto de Estudios Gallegos Padre Sarmiento (ed.). Los judíos en Galicia (in Spanish). A Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. ISBN 84-95892-50-2.

- Boto, Gerardo (2007). "'Monerías' sobre pergamino: La pintura de los márgenes en los códices hispanos bajomedievales (1150–1518)" (PDF). Boletín de Arte (in Spanish) (28). ISSN 0211-8483.

- Gerli, E. Michael, ed. (2003). Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93918-6.

- González López, Emilio (1967). "Un tesouro de arte galego: A Biblia en hebreo da Universidade de Oxford" (PDF). Grial (in Galician) (16).

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin (2004). "The First Kennicott Bible". Jewish Book Art between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13789-0.

- Roth, Cecil (1959). The Jews in the Renaissance. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

External links

- Bodleian Library MS. Kennicott 1 at Digital Bodleian

- The Kennicott Bible (educational video) at PBS LearningMedia