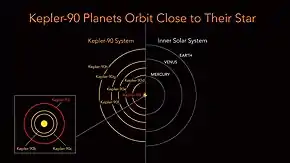

Illustration of the Kepler-90 system compared to the inner solar system. Kepler-90h is the outermost planet of the Kepler-90 system. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Kepler spacecraft |

| Discovery date | November 12, 2013[1] |

| Transit[2] | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 1.01 ± 0.11 AU (151,000,000 ± 16,000,000 km)[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0 ≤ 0.001[1] |

| 331.60 ± 0.00037[1] d | |

| Inclination | 89.6 ± 1.3[2] |

| Star | Kepler-90 |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 1.01 (± 0.09)[3] RJ |

| Mass | 0.639±0.016[4] MJ |

| Temperature | 292 K (19 °C; 66 °F)[2] |

Kepler-90h (also known by its Kepler Object of Interest designation KOI-351.01) is an exoplanet orbiting within the habitable zone of the early G-type main sequence star Kepler-90, the outermost of eight such planets discovered by NASA's Kepler spacecraft. It is located about 2,840 light-years (870 parsecs), from Earth in the constellation Draco. The exoplanet was found by using the transit method, in which the dimming effect that a planet causes as it crosses in front of its star is measured.

Characteristics

Physical characteristics

Kepler-90h is a gas giant with no solid surface. Its equilibrium temperature is 292 K (19 °C; 66 °F).[3] It is around 0.64 times as massive and around 1.01 times as large as Jupiter.[3] This makes it very similar to Jupiter, in terms of mass and radius.[3]

Orbit

Kepler-90h orbits its host star about every 331.6 days at a distance of 1.01 astronomical units, very similar to Earth's orbital distance from the Sun (which is 1 AU).[3]

Habitability

Kepler-90h resides in the circumstellar habitable zone of the parent star. The exoplanet, with a radius of 1.01 RJ, is too large to be rocky, and because of this the planet itself may not be habitable. Hypothetically, large enough moons, with a sufficient atmosphere and pressure, may be able to support liquid water and potentially life.

For a stable orbit the ratio between the moon's orbital period Ps around its primary and that of the primary around its star Pp must be < 1/9, e.g. if a planet takes 90 days to orbit its star, the maximum stable orbit for a moon of that planet is less than 10 days.[5][6] Simulations suggest that a moon with an orbital period less than about 45 to 60 days will remain safely bound to a massive giant planet or brown dwarf that orbits 1 AU from a Sun-like star.[7] In the case of Kepler-90h, this would be practically the same to have a stable orbit.

Tidal effects could also allow the moon to sustain plate tectonics, which would cause volcanic activity to regulate the moon's temperature[8][9] and create a geodynamo effect which would give the satellite a strong magnetic field.[10]

To support an Earth-like atmosphere for about 4.6 billion years (the age of the Earth), the moon would have to have a Mars-like density and at least a mass of 0.07 MEarth.[11] One way to decrease loss from sputtering is for the moon to have a strong magnetic field that can deflect stellar wind and radiation belts. NASA's Galileo's measurements hints large moons can have magnetic fields; it found that Jupiter's moon Ganymede has its own magnetosphere, even though its mass is only 0.025 MEarth.[7]

Host star

The planet orbits a G-type star named Kepler-90, its host star. The star is 1.2 times as massive as the Sun and is 1.2 times as large as the Sun. It is estimated to be 2 billion years old, with a surface temperature of 6080 K. In comparison, the Sun is about 4.6 billion years old[12] and has a surface temperature of 5778 K.[13]

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 14.[14] It is too dim to be seen with the naked eye, which typically can only see objects with a magnitude around 6 or less.[15]

Discovery

In 2009, NASA's Kepler spacecraft was completing observing stars on its photometer, the instrument it uses to detect transit events, in which a planet crosses in front of and dims its host star for a brief and roughly regular period of time. In this last test, Kepler observed 50000 stars in the Kepler Input Catalog, including Kepler-90; the preliminary light curves were sent to the Kepler science team for analysis, who chose obvious planetary companions from the bunch for follow-up at observatories. Observations for the potential exoplanet candidates took place between 13 May 2009 and 17 March 2012. After observing the respective transits, which for Kepler-90h occurred roughly every 331 days (its orbital period), it was eventually concluded that a planetary body was responsible for the periodic 331-day transits. The discovery, was announced on November 12, 2013.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "TEPcat: Kepler-90h". www.astro.keele.ac.uk. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Planet Kepler-90 h". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Kepler-90 h". NASA Exoplanet Archive. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Liang, Yan; Robnik, Jakob; Seljak, Uroš (2021), "Kepler-90: Giant Transit-timing Variations Reveal a Super-puff", The Astronomical Journal, 161 (4): 202, arXiv:2011.08515, Bibcode:2021AJ....161..202L, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abe6a7, S2CID 226975548

- ↑ Kipping, David (2009). "Transit timing effects due to an exomoon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 392 (1): 181–189. arXiv:0810.2243. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.392..181K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13999.x.

- ↑ Heller, R. (2012). "Exomoon habitability constrained by energy flux and orbital stability". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 545: L8. arXiv:1209.0050. Bibcode:2012A&A...545L...8H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220003. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 118458061.

- 1 2 Andrew J. LePage. "Habitable Moons:What does it take for a moon — or any world — to support life?". SkyandTelescope.com. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Glatzmaier, Gary A. "How Volcanoes Work – Volcano Climate Effects". Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "Solar System Exploration: Io". Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 16 December 2003. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Nave, R. "Magnetic Field of the Earth". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "In Search Of Habitable Moons". Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Fraser Cain (16 September 2008). "How Old is the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Fraser Cain (15 September 2008). "Temperature of the Sun". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ "Planet Kepler-90 b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ Sinnott, Roger W. (19 July 2006). "What's my naked-eye magnitude limit?". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ↑ Schmitt, Joseph R.; Wang, Ji; Fischer, Debra A.; Jek, Kian J.; Moriarty, John C.; Boyajian, Tabetha S.; Schwamb, Megan E.; Lintott, Chris; Smith, Arfon M.; Parrish, Michael; Schawinski, Kevin; Lynn, Stuart; Simpson, Robert; Omohundro, Mark; Winarski, Troy; Goodman, Samuel J.; Jebson, Tony; Lacourse, Daryll (2013). "Planet The First Kepler Eight Planet Candidate System from the Kepler Archival Data", Astrophysical Journal, p. 23.