This is a sub-article to Leningrad–Novgorod Offensive and Battle of Narva.

| Kingisepp–Gdov offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Eastern Front (World War II) | |||||||

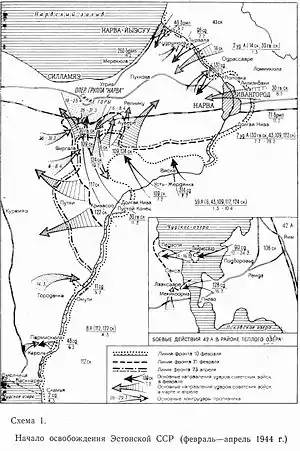

Soviet map of Leningrad–Novgorod offensive | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Georg Lindemann | Leonid A. Govorov | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

One army: 100,000 personnel 1500 artillery 100 armoured vehicles 400 aircraft[1] | Two armies and the Baltic Fleet | ||||||

The Kingisepp–Gdov offensive was a campaign between the Soviet Leningrad Front and the German 18th Army fought for the eastern coast of Lake Peipus and the western banks of the Narva River from 1 February till 1 March 1944. The 109th Rifle Corps captured the town of Kingisepp, forcing the 18th Army into new positions on the eastern bank of the Narva. Forward units of the 2nd Shock Army crossed the river and established several bridgeheads on the west bank, to the north and south of the town of Narva on 2 February. The 8th Army expanded the bridgehead in Krivasoo Swamp south of the town five days later, cutting the railway behind the Sponheimer Group. Army General Leonid Govorov was unable to take advantage of the opportunity of encircling the smaller German detachment which called in reinforcements. These came mostly from the newly mobilised Estonians motivated to resist the looming Soviet re-occupation. At the same time, the Soviet 108th Rifle Corps landed its units across Lake Peipus in Piirissaar Island 120 kilometres south of Narva and established a bridgehead in Meerapalu. By coincidence, the I.Battalion, Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS 45 (1st Estonian) headed for Narva reached the area. The battalion, a battalion of the 44th Infantry Regiment (consisting in personnel from East Prussia), and an air squadron destroyed the Soviet bridgehead on 15–16 February. A simultaneous Soviet amphibious assault was conducted, as the 517 strong 260th Independent Naval Infantry Brigade landed at the coastal borough of Mereküla behind the Sponheimer Group lines. However, the unit was almost completely annihilated.

As the result of the campaign, the Soviet forces seized control of most of the eastern coast of Lake Peipus and established a number of bridgeheads on the western bank of the Narva River.

Background

Combat activity

The 109th Rifle Corps captured the town of Kingisepp on 1 February.[2] Units of the 18th Army fought a rearguard action until it reached the eastern bank of the Narva. The Sponheimer Group blew up the ice on the southern 50 km (31 mi) section of the Narva River from Lake Peipus to Krivasoo Swamp.[3] North of the city, the 4th Soviet Rifle Regiment reached the Narva River, establishing a small bridgehead across it on 2 February.[4][5] The fighting to the east of Narva had left a large number of German troops stranded on the wrong side of the front.[6] Simultaneously, the 122nd Rifle Corps crossed the river south of the town in Vääska settlement, establishing a bridgehead in Krivasoo Swamp 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Narva.[4]

Ivangorod Bridgehead

The main brunt of the Soviet attack was where the Germans had least expected it[4] — the III SS Panzer Corps, positioned east of Narva and holding the German bridgehead on the opposite bank.[4] The SS panzer corps were mostly made up of SS volunteer formations. The 4th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Brigade Nederland and the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland began frantically digging in along what had become known as the Narva line. The defensive line ran for 11 km (6.8 mi), from the estate of Lilienbach 2 km (1.2 mi) northeast from the highway bridge over the Narva River, to the borough of Dolgaya Niva 3 km (1.9 mi) in the south bulging eastwards. The Nederland Brigade defended the northern half of the bridgehead while the Nordland Division held the southern flank. Attacking them along the highway and railway were the four Soviet divisions of the 43rd and the 109th Rifle Corps. The Nederland Brigade, the I.Battalion, SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Regiment 24 Danmark and the German artillery inflicted heavy casualties on the Red Army, who failed to reach their operational goal of destroying the bridgehead.[4]

Krivasoo Bridgehead, first half of February

In the Krivasoo Swamp 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Narva, the Soviet 1078th Regiment and the ski battalion of the 314th Rifle Division crossed the river under a heavy German air and artillery attack in four hours. Despite the resistance of the 29th Estonian Police Battalion, the 314th Rifle Division approached Auvere Railway Station 10 kilometres west of Narva, threatening to cut the railway behind the III SS Panzer Corps and the two division-sized units of the Sponheimer Group. The Soviet author Fyodor Paulman depicts the battles for Auvere Station as ferocious[4] causing serious casualties to the 314th Rifle Division.[7][8] The 125th Rifle Division was sent to assist them.[4] The renewed Soviet units captured the railway crossing near Auvere Station on 6 February, losing it on the same day under the fire of the German coastal artillery. From then on, the Soviet forces remained passive in the direction of Auvere, giving the Sponheimer Group valuable time to regain their strength.[7][8]

Omuti, Permisküla and Gorodenka Bridgeheads

Two Soviet platoons of the 147th Rifle Regiment volunteered to cross the river to the boroughs of Omuti, Permisküla and Gorodenka 40 km (25 mi) south of Narva on 2 February.[4] The bank was defended by the 30th Estonian Police Battalion. The defence was built as an array of small bridgeheads on the east bank, appearing to the Soviets as a carefully prepared defence system in front of the main defence line. Repelled for the first time, the Soviet headquarters took some hours to prepare the attack by the 219th and 320th Rifle Regiments. The Estonians pulled back to their bank during the Soviet attacks, stopping the advance of the Red Army and causing heavy losses.[9] Despite the heroics of the Soviet commanders, only a small platoon commanded by Lieutenant Morozov fortified themselves on the west bank.[4]

Soviet difficulties in February

The Soviet operations were accompanied by major problems in supply, as the major transport connections had been largely destroyed by the Germans and the remaining poor roads were threatening to fall apart in the thaw closing in. Another failure was in intelligence as the Soviet partisan troops that had been sent to Estonia were destroyed.[8] In their report on 8 February, the War Council of the Leningrad Front saw the preparations for the landings across the Narva River as unsatisfactory:[4]

The reconnaissance is unorganized in the army; in the corps and the divisions, there is a lack of a concrete decision on the order of battle and the line-out of batteries; entirely unsolved is the matter of the tanks crossing the river and conducting combat on the left bank; there are no schemes prepared of the engineering support for the attacks. The army (...) lacks an anti-air defence plan; (...)

The Soviet 98th and the 131st Armoured Divisions established a bridgehead on the west bank near the borough of Siivertsi further north from Narva on 12 February.[4] The bridgehead soon became the most critical position on the whole Narva front. If the Soviets succeeded there, the city of Narva would fall quickly and the Narva Bridgehead on the east bank of the river would be cut off. All available units were thrown against the bridgehead.

Auvere Station, 11 February

Army General Leonid Govorov of Leningrad Front ordered the 2nd Shock Army to break through the German defence line north and south of the city of Narva, move the front 50 km (31 mi) westward and continue towards the town of Rakvere. The artillery of the 2nd Shock army opened fire on all German positions on 11 February. The 30th Guards Rifle Corps, an elite unit usually used for breaching defence lines, joined the Soviet units attempting to seize Auvere Station.[8] The guards riflemen widened the bridgehead to 10 km (6.2 mi) along the front. The remains of the German 227th and 170th Infantry Divisions retreated.[4] General Major Romancov ordered an air and artillery assault at the village of Auvere on 13 February, with the 64th Guard Rifle Division seizing the village in a surprise attack. Half a kilometre west of Auvere Station, the 191st Guard Rifle Regiment cut through the railway 2 km (1.2 mi) from Narva–Tallinn Highway, which was the last way out for the Sponheimer Group but was repelled by the 170th Infantry Division and the 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion.[3][4]

Mid-February situation

The situation on the Narva front was turning into a catastrophe for the German Army Group North.[10] The Leningrad Front had formed bridgeheads both north and south of Narva, the closest of them a few hundred meters away from Narva–Tallinn Highway. The Sponheimer Group was in direct danger of getting besieged. The defence of the highway was held only by small infantry units formed of the 9th and 10th Luftwaffe Field Divisions, supported by Panther tanks after every few hundred metres along the highway. They obscured direct observation of the highway by placing branches of spruce trees along it, however, this did not distract the Soviet artillery from keeping the highway under constant bombardment. The faith of the Sponheimer Group, that the defence could go on like this, started to diminish.[8][11]

Soviet landing operations

Meerapalu

Seeing the condition of the front, Hitler ordered the 20th Estonian SS-Volunteer Division to be replaced on the Nevel front and transported to the Narva front. The arrival of the I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment at Tartu coincided with the prepared landing operation by the left flank of the Leningrad Front to the west coast of Lake Peipus, 120 km (75 mi) south of Narva.[3] The Soviet 90th Rifle Division seized Piirissaar Island in the middle of the lake on 12 February.[12] The I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment was placed at the Yershovo Bridgehead on the east coast of Lake Peipus. The 374th Soviet Rifle Regiment crossed Lake Peipus on 14 February, seized the coastal village of Meerapalu in a surprise attack, and formed a bridgehead.[12] Additional units of the 90th Rifle Division attacking across the lake were destroyed by 21 German Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers.[8][13] On the next morning, the 128th Rifle Division established another bridgehead further south in Jõepera. A battalion of the 44th Infantry Regiment, the I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment and the air squadron cleared the west coast of the Soviets on the same day. Estonian sources estimate the Soviet casualties to be in the thousands.[8][14] The East-Prussian battalion regained Piirissaar island on 17 February.[8]

Mereküla

To break the last resistance simultaneously with the Meerapalu Landing Operation, Govorov ordered the 260th Independent Naval Infantry Brigade to prepare for an amphibious attack to the German rear in Narva.[3] This was an elite unit specially trained for an amphibious assault.[3] They were transported to Narva Font by a navy unit of 26 vessels.[5] The troops were to assault from the Gulf of Finland, landing several kilometers behind the German lines near the coastal borough of Mereküla. The first company were to destroy the railway and Auvere Station, the second company to occupy the railway east from Auvere and the third company to cover the left flank and to blow up the railway bridge east of Auvere.[5] Estonian sources claim upon the testimonies of the captured Soviet Major Sinkov and Captain Sapolkin that as the instructions for later action, Major Maslov had ordered to slaughter the civilians which was confirmed by the murder of a family.[10][15] Another amphibious unit was intended to land after them.[5] However, the Estonian Counterintelligence had acquired data on an amphibious operation being prepared to land in Mereküla in 1939. Preparing the Panther Line in 1944, the Germans placed their artillery on the coastal battery built by the Military of Estonia specifically against such a landing.[8] The 517 troops commenced their operation on 14 February, landing directly in front of the German coastal artillery. The Norge Regiment and the coastal guards, supported by three Tiger I tanks quickly responded. While the 8th Army artillery placed near Auvere failed to begin their attack at the agreed time,[16] in seven and a half hours of fierce fighting, the Soviet beachhead was annihilated.[7][8]

Aftermath

References

- ↑ Jaan Kuningas. "1944. aasta veebruar. Võitlus Narva pärast (February 1944. Battle for Narva)" (in Estonian). Postimees. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ David M. Glantz (2002). The Battle for Leningrad: 1941-1944. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700612086.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Toomas Hiio (2006). "Combat in Estonia in 1944". In Toomas Hiio; Meelis Maripuu; Indrek Paavle (eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1035–1094.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 F.I.Paulman (1980). Ot Narvy do Syrve (From Narva to Sõrve) (in Russian). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- 1 2 3 4 Евгений Кривошеев; Николай Костин (1984). "I. Sraženie dlinoj v polgoda (Half a year of combat)". Битва за Нарву, февраль-сентябрь 1944 год (The Battle for Narva, February-September 1944) (in Russian). Tallinn: Eesti raamat. pp. 9–87.

- ↑ Marc Rikmenspoel (1999). Soldiers of the Waffen SS. J.J. Fedorowicz, Winnipeg

- 1 2 3 Unpublished material from the official war diary of army detachment "Narwa"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mart Laar (2006). Sinimäed 1944: II maailmasõja lahingud Kirde-Eestis (Sinimäed Hills 1944: Battles of II World War in Northeast Estonia) (in Estonian). Tallinn: Varrak.

- ↑ (in Estonian) Voldemar Madisso (1997). Nii nagu see oli. (As It Was) SE & JS, Tallinn

- 1 2 Laar, Mart (2005). Estonia in World War II. Tallinn: Grenader.

- ↑ (in Estonian) Karl Gailit (1995). Eesti sõdur sõjatules. (Estonian Soldier in Warfare.) Estonian Academy of National Defense Press, Tallinn

- 1 2 L. Lentsman (1977). Eesti rahvas Suures Isamaasõjas (Estonian Nation in Great Patriotic War) (in Estonian). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- ↑ (in Estonian) A. Kübar (1993). Veebruar 1944. Viru Sõna, March 9 (February 1944).

- ↑ Harald Riipalu (1951). Siis, kui võideldi kodupinna eest (When Home Ground Was Fought For) (in Estonian). London: Eesti Hääl.

- ↑ (in Estonian) Eesti Sõna (1944). Testimony of Major Sinkov

- ↑ (in Russian) Bor'ba za Sovetskuyu Pribaltiku v Velikoj Otechestvennoy Voyne (Fight for Soviet Baltics in the Great Patriotic War). Vol. 3. Liesma, Riga