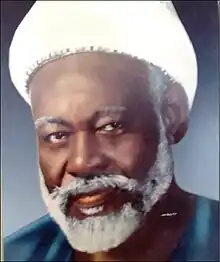

The Islamist movement in Sudan started in universities and high schools as early as the 1940s under the influence of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[1] The Islamic Liberation Movement, a precursor of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood, began in 1949.[1] Hassan Al-Turabi then took control of it under the name of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood.[1] In 1964, he became secretary-general of the Islamic Charter Front (ICF), an activist movement that served as the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood.[1] Other Islamist groups in Sudan included the Front of the Islamic Pact and the Party of the Islamic Bloc.[1][2]

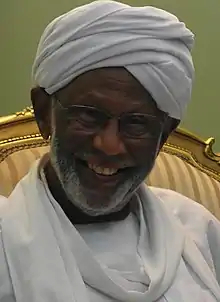

As of 2011, Al-Turabi, who created the Islamist Popular Congress Party, had been the leader of Islamists in Sudan for the last half century.[1] Al-Turabi's philosophy drew selectively from Sudanese, Islamic, and Western political thought to fashion an ideology for the pursuit of power.[1] Al-Turabi supported sharia and the concept of an Islamic state, but his vision was not Wahhabi or Salafi.[1] He appreciated that the majority of Sudanese followed Sufi Islam, which he set out to change with new ideas.[1] He did not extend legitimacy to Sufis, Mahdists, and clerics, whom he saw as incapable of addressing the challenges of modern life.[1] One of the strengths of his vision was to consider different trends in Islam.[1] Although the political base for his ideas was probably relatively small, he had an important influence on Sudanese politics and religion.[1]

Following the 2018–2019 Sudanese Revolution and 2019 coup, the future of Islamism in Sudan was in question.[3][4]

Early years: al-Mirghani and al-Mahdi rivalry

Under the Turco-Egyptian rule, Sudan saw the rise of politically driven religious movements. This was highlighted by the Mahdist Uprising in 1843, led by Muhammad Ahmad against the Turco-Egyptian rule. After liberating Khartoum and killing General Charles Gordon, the Mahdist state was established in 1885. Despite its defeat by British forces in 1899, the movement's influence persisted with its followers known as "Ansar." and later, in February 1945, forming the "Umma" Party by Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi to advocate for Sudan's independence from Anglo-Egyptian rule.[5]

Conversely, during the Turco-Egyptian rule in Sudan, the "Khatmiyyah," established by Muhammad Othman al-Mirghani al-Khitmi in 1817, received support. It remained influential during the British occupation and served as a rival to the Ansar movement. In 1943, the Khatmiyyah leader backed the "brothers" movement and the Unity of the Nile Valley movement, advocating for Sudan's autonomy within a united structure with Egypt, which later became the "National Unionist Party (NUP)."[5] despite Khatmiyyah still receiving an annual British endowment, the British, concerned about Khatmiyyah's growing political influence, have sought to counteract this by bolstering the political position of Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi.[6] The Khatmiyyah split from the NUP in June 1956 to form "The People's Democratic Party," which eventually merged with the Democratic Unionist Party in December 1967.[5]

Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan (1954–1964)

The Muslim Brotherhood's presence in Sudan was initiated by Jamal al-Din al-Sanhuri in 1946. By 1948, the organisation had grown to include fifty branches in Sudan. However, the British authorities denied the group permission to operate.[5]

In 1949, the "Islamic Liberation Movement" emerged at Gordon Memorial College, aiming to counter communist influence among students. Despite ideological similarities with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, the movement distanced itself from it. The Eid Conference of August 1954 resolved leadership conflicts, leading to the adoption of the name "The Muslim Brotherhood" for the movement in Sudan. This decision caused divisions, resulting in the formation of the Islamic Group in 1954 and the Islamic Socialist Party in 1964.[5]

The Muslim Brotherhood's political engagement increased in December 1955, leading to the establishment of the "Islamic Front for the Constitution." The front advocated for an Islamic constitution after independence.[5]

In 1959, Al-Rashid al-Taher, a leader of the Sudanese Brotherhood, was arrested for alleged involvement in the 1959 coup attempt. His removal led to a decline in the group's activities. Meanwhile, the Islamic Group and the Islamic Socialist Party faced limited success. Babikr Karar's ideas, which aimed to reconcile Islam, socialism, and Arab nationalism, did not gain significant attention. After the 1969 Numeiri coup, Karar relocated to Libya following the September Al-Fateh Revolution. His later attempts to revive the experiment achieved limited success.[5]

Islamic Charter Front (1964–1969)

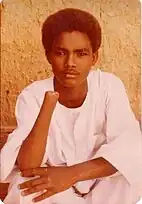

Hassan al-Turabi, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Khartoum, rose to prominence during the October 1964 revolution. He then founded the "Islamic Charter Front," which aimed to establish an Islamic constitution and united several Islamic groups. The Front won seven seats in the 1965 elections but saw a decrease in the 1968 elections. Al-Turabi expanded the Front’s membership and turned it into a pressure group that led to the banning of the Sudanese Communist Party in November 1965. After his election as Attorney General in April 1969, some members left the group due to his political approach. However, this split remained inactive due to the coup by Nimeiri and the subsequent Mayo regime.[5]

National Reconciliation

Following a failed coup attempt in June 1976, Gaafar Nimeiry sought "national reconciliation" and integrated Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi and Al-Turabi into the Sudanese Socialist Union’s political bureau. Al-Turabi became Attorney General in 1979. Al-Turabi saw the rebuilding of the organisation after the coup and exile as a strategic choice. He also took advantage of Nimeiri’s suppression of the communists after their 1971 coup attempt.

In 1979, a disagreement between the Sudanese Brotherhood and the parent organization led to a split. Al-Turabi refused to pledge allegiance to the international group, and Sheikh Sadiq and his followers sided with him. Al-Turabi named his faction the "Sudanese Islamic Movement"[5]

Al-Turabi’s influence reached its height when Nimeiri implemented Sharia laws in September 1983, a move Al-Turabi supported. Al-Turabi and his allies within the regime opposed self-rule in the south, a secular constitution, and the acceptance of non-Islamic culture. A condition for national reconciliation was to reconsider the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement that granted self-governance to the south.[5]

Sharia laws

In September 1983, President Jaafar Nimeiri introduced sharia law in Sudan, known as September 1983 laws, symbolically disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments like public amputations. The Islamic economy followed in early 1984, eliminating interest and instituting zakat. Nimeiri declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma in 1984.[7]

Nimeiri's attempt at implementing an "Islamic path" in Sudan from 1977 to 1985, including aligning with religious factions, ultimately failed. His transition from nationalist leftist ideologies to strict Islam was detailed in his books "Al-Nahj al-Islami limadha?" and "Al-Nahj al-Islami kayfa?" The connection between Islamic revival and reconciling with opponents of the 1969 revolution coincided with the rise of militant Islam in other parts of the world. Nimeiri's association with the Abu Qurun Sufi order influenced his shift towards Islam, leading him to appoint followers of the order into significant roles. The process of legislating the "Islamic path" began in 1983, culminating in the enactment of various orders and acts to implement sharia law and other Islamic principles.[7]

Nimeiri's establishment of the Islamic state in Sudan was outlined in his speech at a 1984 Islamic conference. He justified the implementation of the sharia due to a rising crime rate. He claimed a reduction of crime by over 40% within a year due to the new punishments. Nimeiri attributed Sudan's economic success to the zakat and taxation act, outlining its benefits for the poor and non-Muslims. His association with the Abu Qurun Sufi order and his self-proclaimed position as imam led to his belief that he alone could interpret laws in line with the sharia. However, his economic policies, including Islamic banking, led to severe economic issues. Nimeiri's collaboration with the Muslim Brotherhood and the Ansar aimed to end sectarian divisions and implement the sharia. The Ansar, despite initial collaboration, criticized Nimeiri's implementation as un-Islamic and corrupt.[7]

Nimeiri's Islamic phase resulted in renewed conflict in Southern Sudan in 1983, marking the end of the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, which had granted regional autonomy and recognized the diverse nature of Sudanese society. The agreement ensured equality regardless of race or religion and allowed for separate personal laws for non-Muslims. However, hostilities escalated due to oil discovery, dissolution of the Southern Regional Assembly, and decentralization efforts. Despite this, the Islamic laws implemented by Nimeiri exacerbated the situation. The political landscape shifted with Nimeiri's removal in 1985, leading to the emergence of numerous political parties. The National Islamic Front (NIF), Ansar, and Khatmiyya Sufi order (DUP) played crucial roles in Sudan's politics. Hasan al-Turabi and the NIF consistently supported the Islamic laws and resisted changes.[7]

Another Islamic movement in Sudan was the Republican Brotherhood, founded by Mahmoud Muhammad Taha. This movement embraced the concept of Islam having two messages and abandoned numerous Islamic practices. It advocated for peaceful coexistence with Israel, gender equality, criticised Wahhabism, called for freedoms and refraining from implementing Islamic criminal punishments, and championed a federal social democratic government. Taha strongly opposed the ban on the Sudanese Communist Party and condemned the decision as a distortion of democracy, even though he wasn't a communist. He was sentenced to apostasy in 1968 and again in 1984, leading to his execution in January 1985 under the September laws, despite his strong opposition. This event significantly fuelled public and international discontent.[5]

National Islamic Front (1985–1989)

Following the fall of Nimeiri's regime, al-Turabi and his associates established the "National Islamic Front." This newly formed group participated in the Constituent Assembly elections and secured the third position, amassing 54 seats. This achievement positioned them as the leading opposition force. Al-Turabi once again excelled in playing the role of a influential opposition party, effectively thwarting Sadiq al-Mahdi's endeavour—head of the government and the parliamentary majority—to suspend the contentious September laws and push forward peace negotiations with the southern region.[5]

In response to mounting pressures, Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi was compelled to forge an alliance with the National Islamic Front on 15 May 1988. This alliance resulted in the establishment of the Government of National Accord, in which al-Turabi assumed the role of Minister of Justice with the task of reshaping Sharia laws. Meanwhile, both parties—the nation and the front—confronted a peace agreement brokered by Muhammad Othman al-Mirghani, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and head of the Sovereignty Council, with the "Sudan People's Liberation Army." This rebel movement, led by John Garang, was the primary opposition force in the south and was engaged in a fierce conflict with the Sudanese army.[5] Meanwhile, Sadiq al-Mahdi, leader of the Ansar and prime minister during Sudan's third democratic episode, initially opposed the Islamic laws he later supported. He proposed a vision of a fully Arabized and Islamized southern Sudan, aiming for unity but differing from his earlier, more liberal views. The failure to address Sudan's issues led to the military coup by Omar al-Bashir in 1989, further entrenching Islamic principles.[7]

In light of the escalating challenges concerning southern peace negotiations and the September Laws, Sadiq al-Mahdi was compelled to re-establish the Government of National Accord in February 1988. The Front's influence within the coalition expanded, resulting in al-Turabi assuming the position of Foreign Minister. This move raised concerns in Egypt, which regarded al-Turabi as an extremist Islamist figure. In February 1989, the army issued a memorandum to the government, urging the approval of the peace agreement brokered by Al-Mirghani and the resolution of the worsening economic situation. The National Islamic Front perceived this memorandum as directed against them, given their strong opposition to peace negotiations with the southern region.[5]

Kizan Era (1989–1999)

On 30 June 1989, Brigadier General Omar al-Bashir executed a coup against the existing democratic government. In the coup's proclamation, labelled the "National Rescue Revolution," al-Bashir cited the economic shortcomings of the Mahdi administration and its inability to establish relations with Central Africa as reasons for the coup. This reasoning was met with scepticism. Subsequently, al-Bashir detained numerous political leaders, including Hassan al-Turabi. Egypt expressed approval of this move.[5]

In a remarkable turn of events in December, the officers of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation publicly pledged loyalty to Hassan al-Turabi, who they had previously arrested. Together with the leaders of the National Islamic Front, al-Turabi established the "Council of Defenders of the Revolution," also known as the "Committee of Forty," which took on effective political leadership.[5]

The process of solidifying and Islamising the new regime unfolded using familiar tools of authoritarian rule. A political security apparatus named the "Internal Security" was established, led by Colonel (later Major General) Bakri Hassan Saleh. This body conducted arrests and engaged in torture of those suspected of disloyalty to the regime. Its notorious detention facilities, known as "ghost houses," gained notoriety. Intellectuals such as Muhammad Omar al-Bashir, a distinguished historian and University of Khartoum professor, were among those dismissed, detained, and subjected to torture.[5]

The regime introduced a new penal code in December 1991, which seemed even more stringent than the September laws. The establishment of the "People's Police," akin to Saudi Arabia's Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, occurred. Fundamental public freedoms eroded, including the right to form unions, and political parties were abolished.

Interestingly, prior to these events, both al-Turabi and his wife, Wissal Al-Mahdi (the sister of his rival Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi), held open jurisprudential positions that sparked criticism from religious scholars. Al-Turabi had also advocated for constitutional rule, yet this stance did not align with the social policies of the Salvation regime that he helped establish.[5]

Al-Turabi also made efforts in international realms, attempting to establish an "Islamic International" and reconcile with leftist and nationalist groups to counter imperialism. In April 1991, he founded the "Arab and Islamic People's Conference," attended by representatives from various countries, including the Philippines' Abu Sayyaf group and the Muslim Brotherhood. Later that year, Osama bin Laden relocated to Khartoum and was welcomed by al-Turabi, who even facilitated bin Laden's marriage to a relative. Training camps for armed Islamic groups from different nations were established in Sudan, and al-Turabi attempted mediation between Hamas and the Palestine Liberation Organization.[5]

Al-Turabi's involvement with the Egyptian Islamic Jihad in a plot to assassinate Egyptian President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak in 1995 drew significant attention. Sanctions imposed by the United Nations on Sudan in 1996 isolated the country, causing Bin Laden to depart and al-Turabi's influence to wane. The extradition of leftist activist/terrorist Carlos the Jackal to France in 1994 also sparked discontent within the National Front itself toward al-Turabi.[5]

After a decade of tumultuous events, al-Bashir removed al-Turabi from the presidency of the National Council in 1999. Subsequently, al-Turabi was ousted from the General Secretariat of the National Congress Party. In response, al-Turabi established the "Popular Congress Party." Interestingly, he pragmatically signed a memorandum of understanding with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement, an erstwhile enemy. This eventually led to al-Turabi's imprisonment.[5]

During the internal power struggle between al-Bashir and al-Turabi, the core body of the Sudanese Islamic Movement aligned with al-Bashir. Prominent among them was Ali Othman Taha, a powerful Islamist figure who held the position of vice president from 1998 to 2013. During this period, the regime became highly militarised, and the Islamists, often mockingly referred to as "Kizans" (Sudanese Arabic for cups) due to al-Turabi's saying, "Religion is a sea, and we are its cup (kizan)".[5]

New Islamic Movements

Sheikh Sadiq Abdullah Abdul Majid continued to lead the Muslim Brotherhood's international organization branch, alongside Professor Youssef Nour Al-Daim. The group encountered a crisis in 1991 when the extremist Salafist and Wahhabi wing led by Sheikh Suleiman Abu Naro won elections. This resulted in the traditional wing rejecting the General Shura Council. Sheikh Abu Naro's faction separated into two groups: the "Reform Group," which eventually reunited with the main organization, and the "Sit-Into the Qur'an and Sunnah Movement," which leaned toward extremist Salafism and gradually edged closer to jihadist Salafism. Sheikh Abu Naro passed away in 2014, and Sheikh Omar Abdul Khaleq succeeded him, gaining prominence for declaring support for the Islamic State (ISIS).[5]

In 2012, Sheikh Ali Jawish was elected as the group's general observer in Sudan. Under Ali Jawish's leadership, a division emerged between two wings: the conservative traditional wing, led by Jawish, focused on maintaining ties with the mother organisation in Egypt after its challenges starting in 2013; and the political reform wing represented by the group's Shura Council. This division led Jawish to dissolve the Shura Council in June 2016 and postpone the General Conference for a year. The General Conference re-elected Jawish in March 2017 but dismissed him in December of the same year. Awadallah Hussein, a professor at Omdurman Islamic University's Faculty of Medicine, was chosen as the group's general observer. However, Jawish retained the title with international organisation support until his passing in December.[5]

After Turabi's overthrow, the Brotherhood participated in the Bashir regime's governments. Yet, the group joined the December 2018 protest, aligning closely with the Forces of Freedom and Change, although not being a formal member. Presently, the group wields limited popular, organisational, or cultural influence.[5]

Conversely, recent years have seen the emergence of smaller Islamic groups that either split from other movements or were founded by young Islamic intellectuals. Among these is the "Reform Now" movement led by Ghazi Salah al-Din, a former leader of the ruling National Congress Party who separated from the party in 2013. This movement leads the "National Front for Change" coalition, encompassing the Islamist-leaning East Party for Justice and Development, the Democratic Unionist Party, and other parties.[5]

The National Coordination Initiative for Change and Construction forms a coalition of moderate Islamists. This initiative includes the "National Change Initiative" headed by Ambassador Al-Shafi' Ahmed Mohamed, a former Secretary-General of the ruling party. Almhabob Abdul Salam, a dedicated student of Hassan al-Turabi, broke away from the Popular Congress Party to establish the "Democratic Islamists" movement. Also, Muhammad Al-Majzoub, a political science professor at Al Neelain University with expertise in Islamic political thought, founded "The Initiative for the Transition towards Freedoms and Peaceful Deliberation."[5]

The "Reform and Renaissance Initiative (Tourists)" also signed the initiative, comprising from former fighters who fought against the "Sudan People's Liberation Movement" in the south. They hold a critical stance toward the Bashir regime after secession, emphasising the need for Islamists to relinquish state power and prioritize social reform. This initiative is led by Fatah Al-Alim Abdel-Hay. Additionally, the "Future Now Initiative," led by Mustafa Idris, former president of the University of Khartoum and a former member of the Sudanese Islamic Movement, is part of this movement landscape.[5]

Further reading

- An-Na'im, Abdullahi Ahmed (1989). "Constitutionalism and Islamization in the Sudan". Africa Today. 36 (3/4): 11–28. ISSN 0001-9887.

- Noble-Frapin, Ben (2009). "The Role of Islam in Sudanese Politics: a Socio-Historical Perspective". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 20: 69–82. ISSN 0332-1460.

- Warburg, Gabriel R. (October 1985). "Islam and State in Numayri's Sudan". Africa. 55 (4): 400–413. doi:10.2307/1160174. ISSN 1750-0184.

- Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (1990). "Islamization in Sudan: A Critical Assessment". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 610–623. ISSN 0026-3141.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Shinn, David H. (2015). "Popular Congress Party" (PDF). In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan : a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 254–256. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Zahid, Mohammed; Medley, Michael (2006). "Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt & Sudan". Review of African Political Economy. 33 (110): 693–708. ISSN 0305-6244. JSTOR 4007135.

- ↑ Assal, Munzoul A. M. (2019). "Sudan's popular uprising and the demise of Islamism". Chr. Michelsen Institute. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ↑ Beaumont, Peter; Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (2 May 2019). "Sudan: what future for the country's Islamists?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 هدهود, محمود (15 April 2019). "تاريخ الحركة الإسلامية في السودان". إضاءات (in Arabic). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ "Rivalry between the Two Sayyids al-Mirghani and al-Mahdi" (PDF). CIA. 27 August 1948.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Warburg, Gabriel R. (1990). "The Sharia in Sudan: Implementation and Repercussions, 1983-1989". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 624–637. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328194.