| Louisiana Creole | |

|---|---|

| Creole French | |

| Kouri-Vini,[1] Kréyòl,[2] Fransé[3] | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Louisiana, (particularly St. Martin Parish, Natchitoches Parish, St. Landry Parish, Jefferson Parish, Lafayette Parish, Calcasieu Parish, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana and New Orleans); also in California (chiefly Southern California), Illinois, and in Texas (chiefly East Texas). |

| Ethnicity | Louisiana French (Cajun, Creole) |

Native speakers | <10,000 (2023)[4] |

Creole

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lou |

| Glottolog | loui1240 |

| ELP | Louisiana Creole |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAC-ca |

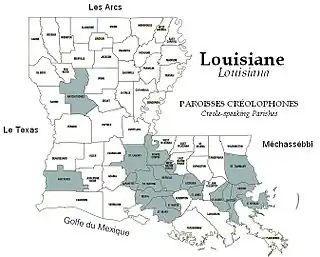

Creole-speaking parishes in Louisiana | |

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana.[4] Also known as Kouri-Vini,[1] it is spoken today by people who may racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and Native American, as well as Cajun and Creole. It should not be confused with its sister language, Louisiana French, a dialect of the French language. Many Louisiana Creoles do not speak the Louisiana Creole language and may instead use French or English as their everyday languages.

Due to the rapidly shrinking number of speakers, Louisiana Creole is considered an endangered language.[5]

Origins and historical development

Louisiana was colonized by the French beginning in 1699, as well as Acadians who were forced out of Acadia around the mid-18th century.[6][7] Colonists were large-scale planters, small-scale homesteaders, and cattle ranchers; the French needed laborers as they found the climate very harsh. They began to import enslaved Africans, as they had for workers on their Caribbean island colonies.[7] It is estimated that, beginning about 1719, a total of 70,000 persons were transported from the Senegambia region of West Africa. These people originally spoke a Mande language related to Malinke. They were in contact with enslaved people speaking other languages, such as Ewe, Fon, and Igbo. The importation of enslaved people by the French regime continued until 1743.[7]

The language developed in 18th-century Louisiana from interactions among speakers of the lexifier language of Standard French and several substrate or adstrate languages from Africa.[8][7] Prior to its establishment as a creole, the precursor was considered a pidgin language.[9] The social situation that gave rise to the Louisiana Creole language was unique, in that the lexifier language was the language found at the contact site. More often the lexifier is the language that arrives at the contact site belonging to the substrate/adstrate languages. Neither the French, the French-Canadians, nor the enslaved Africans were native to the area; this fact categorizes Louisiana Creole as a contact language that arose between exogenous ethnicities.[10] Once the pidgin tongue was transmitted to the next generation as a lingua franca (who were considered the first native speakers of the new grammar), it could effectively be classified as a creole language.[7][8]

No standard name for the language has existed historically. In the language, community members in various areas of Louisiana and elsewhere have referred to it by many expressions, though Kréyol/Kréyòl has been the most widespread. Until the rise of Cajunism in the 1970s and 1980s, many Louisiana Francophones also identified their language as Créole, since they self-identified as Louisiana Creoles. In Louisiana's case, self-identity has determined how locals identify the language they speak. This leads to linguistic confusion. To remedy this, language activists beginning in the 2010s began promoting the term Kouri-Vini, to avoid any linguistic ambiguity with Louisiana French.[1]

The boundaries of historical Louisiana were first shaped by the French, then in statehood after 1812 took on its modern form. By the time of the Louisiana Purchase by the U.S in 1803, the boundaries came to include most of the Central U.S, ranging from present-day Montana; parts of North Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado; all of South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas; part of Southeast Texas; all of Oklahoma; most of Missouri and Arkansas; as well as Louisiana.[11]

In 1978, researchers located a document from a murder trial in the colonial period that acknowledges the existence of Louisiana Creole.[7][11] The documentation does not include any examples of orthography or structure.[7][11]

In an 1807 document, a grammatical description of the language is included in the experiences of an enslaved woman recorded by C.C. Robin. This was prior to arrival in Louisiana of French-speaking colonists and enslaved Africans from Saint-Domingue; the whites and free people of color (also French speaking), were refugees from the Haitian Revolution, that had established the first empire in the western hemisphere. The statements collected from Robin showed linguistic features that are now known to be typical of Louisiana Creole.[7]

The term “Criollo” appears in legal court documents during the Spanish colonial period (1762-1803); the Spanish reference to the language stated that the language was used among enslaved people and whites.[11]

The importation of enslaved Africans increased after France ceded the colony to Spain in 1763, following France's defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years' War in Europe.[12] Some Spaniards immigrated to the colony, but it was dominated by French language and culture. Like South Carolina, Louisiana had a "minority" population of Africans that greatly outnumbered the European settlers, including those white Creoles born in the colony.[7]

Language shift, endangerment and revitalization

In the case of Louisiana Creole, a diglossia resulted between Louisiana Creole and Louisiana French. Michael Picone, a lexicographer, proposed the term "Plantation Society French" to describe a version of French which he associated with plantation owners, plantation overseers, small landowners, military officers/soldiers and bilingual, free people of color, as being a contributor to Louisiana Creole's lexical base. Over the centuries, Louisiana Creole's negative associations with slavery stigmatized the language to the point where many speakers are reluctant to use it for fear of ridicule. In this way, the assignment of "high" variety (or H language) was allotted to standard Louisiana French and that of "low" variety (or L language) was given to Louisiana Creole and to Louisiana French.[13]

The social status of Louisiana Creole further declined as a result of the Louisiana Purchase. Americans and their government made it illegal for Louisiana Creoles to speak their language. Public institutions like schools refused to teach children in their native tongue and children and adults were often punished by corporal punishment, fines, and social degradation. By the 21st century, other methods were enforced. The promise of upward socioeconomic mobility and public shaming did the rest of the work, prompting many speakers of Louisiana Creole to abandon their stigmatised language in favor of English.[14] Additionally, the development of industry, technology and infrastructure in Louisiana reduced the isolation of Louisiana Creolophone communities and resulted in the arrival of more English-speakers, resulting in further exposure to English. Because of this, Louisiana Creole exhibits more recent influence from English, including loanwords, code-switching and syntactic calquing.[15][16][17]

Today, Louisiana Creole is spoken by fewer than 6,000 people.[1][4] Though national census data includes figures on language usage, these are often unreliable in Louisiana due to respondents' tendencies to identify their language in line with their ethnic identity. For example, speakers of Louisiana Creole who identify as Cajuns often label their language 'Cajun French', though on linguistic grounds their language would be considered Louisiana Creole.[18]

Efforts to revitalize French in Louisiana have placed emphasis on Cajun French, to the exclusion of Creole.[19] Zydeco musician Keith Frank has made efforts through the use of social media to not only promote his music, but preserve his Creole heritage and language as well most notably through the use of Twitter. Additionally, Frank developed a mobile application in 2012 titled the "ZydecoBoss App" which acts as a miniature social network linked to a user's Facebook and Twitter accounts, allowing users to provide commentary in real time amongst multiple platforms. Aside from social media activism, Frank also created a creole music festival in 2012 called the "Creole Renaissance Festival", which acts a celebration of Creole culture.[20] A small number of community organizations focus on promoting Louisiana Creole, for example CREOLE, Inc.[21] and the 'Creole Table' founded by Velma Johnson.[22] Northwestern State University developed the Creole Heritage Centre designed to bring people of Louisiana Creole heritage together, as well as preserve Louisiana Creole through their Creole Language Documentation Project.[23] In addition, there is an active online community of language-learners and activists engaged in language revitalization, led by language activist Christophe Landry.[24] These efforts have resulted in the creation of a popular orthography,[25] a digitalized version of Valdman et al.'s Louisiana Creole Dictionary,[26] and a free spaced repetition course for learning vocabulary hosted on Memrise created by a team led by Adrien Guillory-Chatman.[27] A first language primer was released in 2017[28][29] and revised into a full-length language guide and accompanying website in 2020.[2] 2022 saw the publication of an anthology of contemporary poetry in Louisiana Creole, the first book written completely in the language.[30]

Geographic distribution

Speakers of Louisiana Creole are mainly concentrated in south and southwest Louisiana, where the population of Creolophones is distributed across the region. St. Martin Parish forms the heart of the Creole-speaking region. Other sizeable communities exist along Bayou Têche in St. Landry, Avoyelles, Iberia, and St. Mary Parishes. There are smaller communities on False River in Pointe-Coupée Parish, in Terrebonne Parish, and along the lower Mississippi River in Ascension, St. Charles Parish, and St. James and St. John the Baptist parishes.[31]

There once were Creolophones in Natchitoches Parish on Cane River and sizable communities of Louisiana Creole-speakers in adjacent Southeast Texas (Beaumont, Houston, Port Arthur, Galveston)[11][32] and the Chicago area. Natchitoches, being the oldest colonial settlement in Louisiana, proved to be a predominantly creole since its inception.[33] Native inhabitants of the local area Louisiana Creole speakers in California reside in Los Angeles, San Diego and San Bernardino counties and in Northern California (San Francisco Bay Area, Sacramento County, Plumas County, Tehama County, Mono County, and Yuba County).[16] Historically, there were Creole-speaking communities in Mississippi and Alabama (on Mon Louis Island); however, it is likely that no speakers remain in these areas.[34]

Phonology

The phonology of Louisiana Creole has much in common with those of other French-based creole languages. In comparison to most of these languages, however, Louisiana Creole diverges less from the phonology of French in general and Louisiana French in particular.

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Plosive/ | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | |

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||

| Lateral | l | ||||

The table above shows the consonant sounds of Louisiana Creole, not including semivowels /j/ and /w/. In common with Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole features postalveolar affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/, as in /tʃololo/ ‘weak coffee’ and /dʒɛl/ ‘mouth’. The nasal palatal /ɲ/ usually becomes a nasal palatal approximant when between vowels, which results in the preceding vowel becoming nasalized. At the end of a word, it typically is replaced by /n/ or /ŋ/.[35]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||||

| Close | oral | i | y | u | |

| Close-mid | e | ø | o | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | œ | ɔ | ||

| nasal | ɛ̃ | œ̃ | ɔ̃ | ||

| Open | ɑ̃ | ||||

| oral | a | ||||

The table above shows the oral and nasal vowels of Louisiana Creole as identified by linguists.[7]

Vowel rounding

Speakers of the language may use rounded vowels [y], [ø] and [œ] where they occur in French. This is subject to a high degree of variation with the same region, sociolinguistic group, and even within the same speaker.[17][16][36] Examples of this process include:

- /diri/~/dyri/ 'rice', compare French du riz /dyri/

- /vje/~/vjø/ 'old', compare French vieux /vjø/

- /dʒɛl/~/dʒœl/ 'mouth', compare French gueule /ɡœl/[26]

Vowel lowering

The open-mid vowel [ɛ] may lowered to the near-open vowel [æ] when followed by [ɾ], e.g. [fɾɛ]~[fɾæɾ] 'brother'.[7]

Regressive and progressive nasalization of vowels

In common with Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole vowels are nasalized where they precede a nasal consonant, e.g. [ʒɛ̃n] 'young', [pɔ̃m] 'apple'. Unlike most varieties of Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole also exhibits progressive nasalization: vowels following a nasal consonant are nasalized, e.g. [kɔ̃nɛ̃] 'know'.[37]

Grammar

Louisiana Creole exhibits subject-verb-object (SVO) word order.[16]

Determiners

In nineteenth century sources, determiners in Louisiana Creole appear related to specificity. Bare nouns are non-specific. As for specific nouns, if the noun is pre-supposed it took a definite determiner (-la, singular; -la-ye, plural) or by an indefinite determiner (en, singular; de or -ye, plural). Today, definite articles in Louisiana Creole vary between the le, la and lê, placed before the noun as in Louisiana French, and post-positional definite determiners -la for the singular, and -yé for the plural.[35] This variation is but one example of the influence of Louisiana French on Louisiana Creole, especially in the variety spoken along the Bayou Têche which has been characterized by some linguists as decreolized, though this notion is controversial.[17][16][35]

Some speakers of that variety display a highly variable system of number and gender agreement, as evidenced in possessive pronouns.[36]

Personal pronouns[35]

| Subject | Objective | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | mo | mò/mwin | mô (singular); (mâ (singular feminine), mê (plural)) |

| 2nd person | to | twa | tô; (tâ, tê) |

| 3rd person | li | li | sô; (sâ, sê) |

| 1st plural | nou, no, nouzòt | nouzòt | nou, nô, nouzòt |

| 2nd plural | vouzòt, ouzòt, zòt zo | vouzòt, zòt | vouzòt |

| 3rd plural | yé | yé | yê |

Possession is shown by noun-noun possessum-possessor constructions (e.g. lamézon mô papa 'house (of) my grandfather') or with the preposition a (e.g. lamézon a mô papa 'house of my grandfather').[35]

Verbs

Verbal morphology

Older forms of Louisiana Creole featured only one form of each verb without any inflection, e.g. [mɑ̃ʒe] 'to eat'. Today, the language typically features two verb classes: verbs with only a single form ([bwɑ] 'to drink') and verbs with a 'long' or 'short' form ([mɑ̃ʒe], [mɑ̃ʒ] 'to eat').[7]

Tense, aspect, mood

Like other creole languages, Louisiana Creole features preverbal markers of tense, aspect and mood as listed in the table below

| Form | Classification | Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| té | Anterior | Past state of adjectives and stative verbs; pluperfect or habitual past of non-stative verbs.[37] | |

| apé, ap, é | Progressive | Ongoing actions. | Form é is only used in Pointe Coupée.[16] |

| a, va, alé | Future | Future actions | |

| sa | Future states | ||

| sé | Conditional | Actions or states which might take place. | |

| bin | Remote past | "an action or state that began before, and continued up to, a subsequent point in time"[16] | Likely a borrowing from African-American English.[36] |

Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Louisiana Creole is primarily of French origin, as French is the language's lexifier. Some local vocabulary, such as topography, animals, plants are of Amerindian origin. In the domains folklore and Voodoo, the language has a small number of vocabulary items from west and central African languages.[38] Much of this non-French vocabulary is shared with other French-based creole languages of North America, and Louisiana Creole shares all but a handful of its vocabulary with Louisiana French.[39]

Writing system

The current Louisiana Creole alphabet consists of twenty-three letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet (not including c, q, or x) and several special letters and diacritics.[40]

Letter Name[41] Name (IPA) Diacritics Phoneme correspondence[42][25] A a a /a/ Áá, Àà, Ââ /a/ Æ æ æ /æ/ /æ/ B b bé /be/ /b/ Ç ç çé /se/ /s/ D d dé /de/ /d/ E e e /ə/ Éé, Èè, Êê, Ëë e = /ə/; é = /e/; è = /ɛ/ F f èf /ɛf/ /f/ G g gé /ɡe/ /ɡ/ H h hash /haʃ/ /h/ I i i /i/ Íí, Ìì, Îî, Ïï i = /i/; ì = /ɪ/ J j ji /ʒi/ /ʒ/ K k ka /ka/ /k/ L l èl /ɛl/ /l/ M m èmm /ɛm/ /m/ N n ènn /ɛn/ /n/ Ñ ñ ñé /ɲe/ /n/ O o o /o/ Óó, Òò, Ôô, Öö o = /o/; ò = /ɔ/ Œ œ œ /œ/ /œ/ P p pé /pe/ /p/ R r ær, èr /æɾ/, /ɛɾ/ (initial) /r/; (medial) /ɾ/, /r/, /d/, /t/; (final) /ɾ/ S s ès /ɛs/ /s/ T t té /te/ /t/ U u u /y/ Ûû /y/ V v vé /ve/ /v/ W w double-vé /dubləve/ /w/ Y y igrek /iɡɾɛk/ Ÿÿ /j/ Z z zèd /zɛd/ /z/

Language samples

Numbers

Number French Louisiana Creole 1 un un, in 2 deux dé 3 trois trò, trwa 4 quatre kat 5 cinq sink 6 six sis 7 sept sèt 8 huit wit 9 neuf nèf 10 dix dis

Greetings

| English | French | Louisiana Creole |

|---|---|---|

| Hello! | Bonjour ! | Bonjou! |

| How are things? | Comment ça va ? | Konmen lêz afær? |

| How are you doing? | Comment ça va ? | Komen ça va? / Komen ç'apé kouri? |

| I'm good, thanks. | Je vais bien, merci. | Mo byin, mærsi. |

| See you later. | À plus tard. | Wa (twa) plitar. |

| I love you. | Je t'aime. | Mo linm twa. |

| Take care. | Prenez soin de vous/toi. | Swènn-twa / swiñ-twa. |

| Good Morning. | Bonjour. | Bonjou / Bonmatin. |

| Good Evening. | Bonsoir. | Bonswa. |

| Good Night. | Bonne nuit. | Bonnwi / Bonswa. |

Common phrases

| English | French | Louisiana Creole |

|---|---|---|

| The water always goes to the river. | L'eau va toujours à la rivière. | Dilo toujou couri larivière. |

| Tell me who you love, and I'll tell you who you are. | Dites moi qui vous aimez, et je vous dirai qui vous êtes. | Di moin qui vous laimein, ma di vous qui vous yé. |

| Spit in the air, and it will fall on your nose. | Crachez dans l'air, il vous en tombera sur le nez. | Craché nen laire, li va tombé enhaut vou nez. |

| Cutting off the mule's ears doesn't make it a horse. | Couper les oreilles du mulet, n'en fait pas un cheval. | Coupé zoré milet fait pas chewal. |

| Tortoise goes slowly, but he arrives at the barrel while Roe Deer is sleeping. | Compère Tortue va doucement, mais il arrive au bût pendant que Compère Chevreuil dort. | Compé Torti va doucement, mais li rivé coté bite pendant Compé Chivreil apé dormi. |

| The pig knows well on which [tree] wood it will rub. | Le cochon sait bien sur quel [arbre] bois il va se frotter. | Cochon conné sir qui bois l'apé frotté. |

| Whoever laughs on Friday will cry on Sunday. | Celui qui rit le vendredi va pleurer le dimanche. | Cila qui rit vendredi va pleuré dimanche. |

| The barking dog doesn't bite. | Le chien qui jappe ne mord pas. | Chien jappô li pas morde. |

| The burnt cat is afraid of fire. | Le chat brûlé a peur du feu. | Chatte brilé pair di feu. |

| The goat makes the gumbo; the rabbit eats it. | Le bouc fait le gombo ; le lapin le mange. | Bouki fait gombo; lapin mangé li. |

The Lord's Prayer

Catholic prayers are recited in French by speakers of Louisiana Creole. Today, some language activists and learners are leading efforts to translate the prayers.[43]

Nouzòt Popá, ki dan syèl-la

Tokin nom, li sinkifyè,

N'ap spéré pou to

rwayonm arivé, é n'a fé ça

t'olé dan syèl; parèy si latær

Donné-nou jordi dipin tou-lé-jou,

é pardon nouzòt péshé paréy nou pardon

lê moun ki fé nouzòt sikombé tentasyon-la,

Mé délivré nou depi mal.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Teo, Tracey (March 1, 2023). "Rediscovering America: Kouri-Vini: The return of the US' lost language". BBC Travel.

- 1 2 Guillory-Chatman, Adrien; Mayeux, Oliver; Wendte, Nathan; Wiltz, Herbert J. (2020). Ti Liv Kréyòl: A Learner's Guide to Louisiana Creole. New Orleans: TSÒHK. ISBN 978-1527271029.

- ↑ Neumann-Holzschuh, Ingrid; Klingler, Thomas A. (2013), "Louisiana Creole structure dataset", Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures Online, Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, retrieved May 15, 2023

- 1 2 3 Neumann-Holzschuh, Ingrid; Klingler, Thomas A. "Structure dataset 53: Louisiana Creole". APiCS Online. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Louisiana Creole". Ethnologue. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Acadian". Britannica. December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Klinger, Thomas A.; Neumann-Holzschuh, Ingrid (2013). Michaelis, Susanne Maria; Maurer, Phillippe; Haspelmath, Martin; Huber, Magnus (eds.). "Louisiana Creole". The Survey of Pidgin and Creole Languages Volume II: Portuguese-based, Spanish-based, and French-based Languages. UK: Oxford University Press: 229–40.

- 1 2 Klinger, Thomas A. (2003). If I Could Turn My Tongue Like That: The Creole Language of Pointe Coupee parish, Louisiana. Louisiana: Louisiana State University. pp. 3–92.

- ↑ Dubois, Sylvie; Melançon, Megan (2000). "Creole is, Creole Ain't: Diachronic and Synchronic Attitudes Toward Creole Identity in Southern Louisiana". Language in Society. 29 (2): 237–58. doi:10.1017/S0047404500002037. S2CID 144287855.

- ↑ Velupillai, Viveka (2015). Pidgins, Creoles, & Mixed Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 48–50.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wendte, N.A (2018). "Language and Identity Among Louisiana Creoles in Southeast Texas: Initial Observations". Southern Journal of Linguistics. 42: 1–16.

- ↑ "Seven Years War." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Paul Lagasse, and Columbia University, Columbia University Press, 8th edition, 2018. Credo Reference,

- ↑ Carlisle, Aimee Jeanne. "Language Attrition in Louisiana Creole French" (PDF). linguistics.ucdavis.edu. University of California, Davis. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Becky (1993). "The social consequences of writing Louisiana French". Language in Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 67–101. doi:10.1017/s0047404500016924. ISSN 0047-4045. S2CID 145535212.

- ↑ Valdman 1997, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A., Klingler, Thomas (2003). If I could turn my tongue like that : the Creole language of Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807127795. OCLC 846496076.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Neumann, Ingrid (1985). Le créole de Breaux Bridge, Louisiane: étude morphosyntaxique, textes, vocabulaire. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. ISBN 9783871186974.

- ↑ Klingler, Thomas A. (2003). "Language labels and language use among Cajuns and Creoles in Louisiana". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 9 (2).

- ↑ Squint, Kirstin L. (May 4, 2005). "A Linguistic Comparison of Haitian Creole and Louisiana Creole". Postcolonial Text. 1 (2).

- ↑ Demars, Marie (April 8, 2015). ""On A Mission": Preserving Creole Culture One Tweet at a Time. Keith Frank, Zydeco, and the Use of Social Media". Transatlantica. Revue d'études américaines. American Studies Journal (in French) (1). doi:10.4000/transatlantica.7586. ISSN 1765-2766. S2CID 194272954.

- ↑ "CREOLE, Inc". CREOLE, Inc. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ↑ "About Us". www.louisianacreoleinc.org. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ↑ Gillis, Phil. "Creole Heritage Center". Northwestern State University. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ↑ Mayeux, Oliver. 2015. “New Speaker Language: The Morphosyntax of New Speakers of Endangered Languages.” MPhil dissertation, Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge.

- 1 2 Landry, Christophe; St. Laurent, Cliford; Gisclair, Michael; Gaither, Eric; Mayeux, Oliver (2016). A Guide to Louisiana Creole Orthography. Louisiana Historic and Cultural Vistas.

- 1 2 Valdman 1998.

- ↑ "Kouri-Vini (Louisiana Creole Language)". Memrise. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ↑ Wendte, N. A.; Mayeux, Oliver; Wiltz, Herbert (2017). Ti Liv Kréyòl: A Louisiana Creole Primer. Public Domain.

- ↑ "Ti Liv Kréyòl: A Louisiana Creole Primer - Louisiana Historic and Cultural Vistas". Louisiana Historic and Cultural Vistas. August 14, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ↑ Mayers, Jonathan Joseph; Mayeux, Oliver, eds. (2022). Févi (in Louisiana Creole). Shreveport, L.A.: Les Cahiers du Tintamarre. ISBN 978-1-7353605-4-6.

- ↑ Kirstin Squint, A Linguistic and Cultural Comparison of Haitian Creole and Louisiana Creole, postcolonial.org, Accessed March 11, 2014

- ↑ Wendte 2020.

- ↑ Din, Gilbert C. (May 2009). "Colonial Natchitoches: A Creole Community on the Louisiana-Texas Frontier". Western Historical Quarterly. 40 (2): 220. doi:10.1093/whq/40.2.220. ISSN 0043-3810.

- ↑ Marshall, Margaret (1991). "The Creole of Mon Louis Island, Alabama, and the Louisiana Connection". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 6: 73–87. doi:10.1075/jpcl.6.1.05mar.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Klingler, Thomas A.; Neumann-Holzschuh, Ingrid (2013). "Louisiana Creole". In Susanne Maria Michaelis; Philippe Maurer; Martin Haspelmath; Magnus Huber (eds.). The survey of pidgin and creole languages. Volume 2: Portuguese-based, Spanish-based, and French-based languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967770-2.

- 1 2 3 Mayeux, Oliver (July 19, 2019). Rethinking decreolization: Language contact and change in Louisiana Creole (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.41629.

- 1 2 Klingler, Thomas A. (August 1, 2019). "The Louisiana Creole Language Today". In Dajko, Nathalie; Walton, Shana (eds.). Language in Louisiana: Community and Culture. University Press of Mississippi. p. 95. doi:10.2307/j.ctvkwnnm1.14. ISBN 978-1-4968-2386-1. JSTOR j.ctvkwnnm1. S2CID 243597697.

- ↑ Valdman 1998, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Neumann-Holzschuh, Ingrid (2016). "Entre la Caraïbe et l'Amérique du Nord: le créole louisianais et son lexique à la lumière de ses contacts linguistiques et culturels". In Ette, Ottmar; Müller, Gesine (eds.). New Orleans and the global South : Caribbean, Creolization, carnival. Hildesheim: Georg-Olms-Verlag AG. ISBN 978-3487155043. OCLC 973171332.

- ↑ Louisiana Creole Dictionary (2014). "Alphabet". louisianacreoledictionary.com.

- ↑ Christophe Landry (2014). "Louisiana Creole Alphabet (Updated)". YouTube.

- ↑ "Guide to Louisiana Creole Orthography". January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Christophe Landry (2012). "Nouzòt Popá (The Our Father in Louisiana Creole)". Youtube. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021.

Sources

- Valdman, Albert (1997). Valdman, Albert (ed.). French and Creole in Louisiana. New York: Plenum Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5278-6. ISBN 0-306-45464-5. OCLC 863962055.

- Valdman, Albert (1998). Dictionary of Louisiana Creole. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33451-0. OCLC 39147759. Partial preview at Google Books.

- Wendte, N. A. (2020). Creole - a Louisiana label in a Texas Context. New Orleans, LA: Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-716-64756-7. OCLC 1348382332.

Further reading

- Brasseaux, Carl A. (2005). French, Cajun, Creole, Houma : a primer on francophone Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-4778-8. OCLC 774295468. Partial preview at Google Books.

- Dubois, Sylvie; Horvath, Barbara M. (May 1, 2003). "Creoles and Cajuns: A Portrait in Black and White". American Speech. Duke University Press. 78 (2): 192–207. doi:10.1215/00031283-78-2-192. ISSN 0003-1283. S2CID 15155226.

- Fortier, Alcée (1895). Louisiana Folk-Tales in French Dialect and English Translation. Memoirs of the American Folklore Society. Vol. II. Boston and New York: Published for the American Folk-lore Society by Houghton, Mifflin, and Co. hdl:2027/uc1.b3501893. ISSN 0065-8332. OCLC 1127054952 – via HathiTrust.

- Guillory-Chatman, Adrien; Mayeux, Oliver; Wendte, Nathan; Wiltz, Nathan; Mayers, Jonathan (2020). Ti liv Kréyòl : a learner's guide to Louisiana Creole. New Orleans. ISBN 978-1-5272-7102-9. OCLC 1257416565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1992). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-585-32916-1. OCLC 45843432.

- Kein, Sybil (2005). Learn to speak Louisiana French Creole: an introduction. Natchitoches, LA, US: Gumbo People Products. OCLC 144558377.

- Kein, Sybil; Forsloff, Del (2006). Maw-Maw's Creole ABC book. New Orleans, LA, US: Gumbo People Products. OCLC 809926365.

External links

- Learn Louisiana Creole

- Louisiana Creole Dictionary - Online Archived September 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Learn Pointe-Coupée Parish Creole

- Brian J. Costello – La Language Créole de la Paroisse Pointe Coupée

- Centenary University Bibliothèque Tintamarre Texts in Louisiana Creole

- Christophe Landry, Ph.D.

- Le bijou sur le Bayou Teche

- Cajun French (Creole dialect): "C'est Sophie Guidry" by: Emily Lopez on YouTube

- "Allons Manger" Cajun French with Creole dialect

- Oral History Forum I Raphaël Confiant on YouTube

- Bernard, S. "Creoles". KnowLA: Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- "Louisiana Creole". The Endangered Languages Project.

- English - Louisiana creole Glosbe dictionary

- louisiana creole - English Glosbe dictionary