| Lakshana Devi Temple | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) 7th century Lakshana Devi temple, Himachal Pradesh | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Chamba district |

| Deity | Durga, others |

| Location | |

| Location | Bharmour |

| State | Himachal Pradesh |

| Country | India |

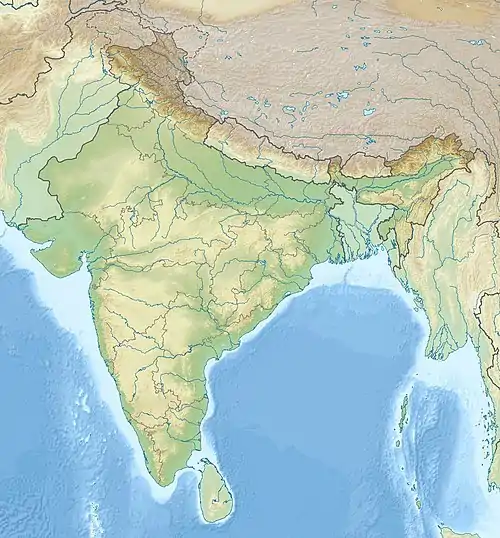

Shown within India  Lakshana Devi Temple, Bharmour (Himachal Pradesh) | |

| Geographic coordinates | 32°26′32.3″N 76°32′14.7″E / 32.442306°N 76.537417°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gupta era |

| Completed | c. 7th-century[1][2] |

| Elevation | 2,135[3] m (7,005 ft) |

The Lakshana Devi Temple in Bharmour is a post-Gupta era Hindu temple in Himachal Pradesh dedicated to Durga in her Mahishasura-mardini form. It is dated to the second half of the 7th-century, and is in part one of the oldest surviving wooden temples in India.[4][1][5]

The temple is the oldest surviving structure of the former capital of Bharmour, also referred to as Bharmaur, Barmawar, Brahmor or Brahmapura in historic texts.[6][7] Its roof and walls have been repaired over the centuries and it looks like a hut, but the Himachal Hindu community has preserved its intricately carved wooden entrance, interior and ceiling that reflects the high art of late Gupta style and era. The design and a late Gupta script inscription below the brass metal goddess statue in its sanctum confirms its antiquity.[6][8] The wooden carvings include Shaivism and Vaishnavism motifs and themes.[9]

Location

The Lakshana Devi temple is in southern part of Bharmour town, and is one of a cluster of Hindu temples built between 7th and 12th-century. It is set in the Himalayas, along the Ravi River and Dhaola dhar range.[7] It is about 400 kilometres (250 mi) northwest of Shimla, about 180 kilometres (110 mi) east of Pathankot (nearest airport, IATA: IXP), and about 110 kilometres (68 mi) from Dalhousie. The town is on Indian Railways network at Bharmar (BHMR) station.[10][11]

History

Bharmour was the capital of Hindu mountain kingdom of Champa, also spelled Chamba. There is no known documented ancient history of the region, and the earliest records appear in the form of inscriptions and legendary texts dated to the second half of the 1st millennium CE. Another source that mentions pre-12th century Champa is the Kashmir text Rajatarangini.[7]

The capital was founded by Meru Varman, and a number of inscriptions in the town and elsewhere in the Chamba valley attest to his rule. The script used and other palaeographic evidence, states Hermann Goetz, dates him to around 700 CE.[12] With the founding of a new capital, Meruvarman commissioned and inaugurated the Lakshana Devi temple. Bharmour is set in secluded mountain valley, one that was difficult to invade and raid. Remote areas such as Bharmour, states Ronald Bernier were "largely spared from the Muslim invasion".[6] According to Goetz and other scholars, this lack of religious persecution may be the reason why Lakshana Devi temple and others in Bharmour have preserved for well over 1,000 years.[13]

Alexander Cunningham was the first archaeologist to visit the Lakshana Devi temple in 1839, who published his comparative analysis in Archaeological Survey of India report.[7] Cunningham remarked, that "the pillars, architraves and the pediment of the doorway are all of wood, most elaborately and deeply carved". The door carvings have weathered and difficult to discern. In contrast, wrote Cunningham, the vestibule inside is well preserved and was "beautifully carved".[7] Jean Vogel visited the Chamba state in the 1900s, and wrote about the temple in his Antiquities of Chamba State in 1911.[14]

Date

The Lakshana Devi temple is dated to around 700 CE based on the temple architecture, plan, artwork, style and the inscription found on the brass statue pedestal in its sanctum.[4][1] The inscription states:

Om! Born from the own-house (gotra) of Mosuna and from the Solar race, the great-grandson of the illustrious lord Aditya-varman, the grandson of the illustrious lord Bala-varman, the son of the illustrious lord Divakara-varman,

(1. 2) the illustrious lord Meru-varman, for the increase of his spiritual merit, has caused the holy image of the goddess Laksana to be made by the workman Gugga.– Laksana Image Inscription, Translated by J. Ph. Vogel[15][note 1]

The inscription mentions Meruvarman and three of his ancestors attested by other texts found in Himachal Pradesh. The reign of Meruvarman is generally dated to have begun in 680 CE.[3] This, traced with other epigraphic and textual evidence, has helped date this temple to be either from late 7th-century or the early 8th.[16]

Description

.jpg.webp)

The temple shows the Gupta era architecture and artwork in wood.[4] It faces north and it currently has a rectangular plan with about 11.6 metres (38 ft) external length and 8.73 metres (28.6 ft) width.[8][9] The temple sits on a square wooden jagati, about 0.45 metres (1 ft 6 in) above the ground. The earlier versions of the temple had a combination of weight bearing wood and non-weight bearing stone walls. The external wall of the temple was later plastered with mud, reaching a current thickness of about 0.85 metres (2 ft 9 in).[9][17]

The entrance and the facade of the temple have been cleaned by the Archaeological Survey of India after 1950s, revealing the finer details that were not visible to Cunningham, Vogel or Goetz. It is similar to the late Gupta style, with three parallel panels surrounding the doorway flanked by river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna.[9] Each band is separated by a thin carving of a floral scroll carved on a convex wood surface. The outer wooden band consists of reliefs of single females standing in tribhanga posture and of amorous couples. The middle wooden band features Ganga standing on makara on left and Yamuna standing on tortoise on right, with their attendants. Above them are a series of Hindu deities, including Shiva with Nandi, Vishnu Vaikunthamurti, four armed Vishnu and Skanda (Kartikeya). A goddess and god in this panel are not identifiable because their iconographic signs are too eroded. The inner panel forms the door frame of the entrance. The inner panel is carved with natural motifs such as leaves and flowers, two peacocks with their beak joined, and a pair of amorous couples in a mithuna scene.[9][18][17]

.jpg.webp)

Above the Gupta era-style carved temple entrance doorway, is a triangular pediment. This is notable for its intricately carved triangular pediment highlighting Vishnu and Garuda. This challenged the colonial era assumption that Shaktism, Shaivism and Vaishnavism may have been competing denominations in Indian history. The Lakshana Devi temple, along with other temples in Chamba valley, attest to all of these traditions being revered together in a Panchaupasana or Panchayatana style. The triangular pediment includes niches containing amorous couples in a range of courtship and intimacy (kama and mithuna) scenes.[1][19]

The temple interior currently has a sandhara plan found in the Hindu texts on architecture. It has an ardha-mandapa, a mukhya-mandapa, a circumambulation path and a rectangular sanctum, about 3.61 metres (11.8 ft) by 2.52 metres (8 ft 3 in). The mukhya-mandapa is a gathering zone in front of the sanctum and marked by six square pillars, each with 22 centimetres (8.7 in) side.[9] The pillars are 2.2 metres (7 ft 3 in) in height. The roof is pitch gabled, topped with slates. The original roof extended up to the main entrance. A roof projection to act as a canopy was added by the Archaeological Survey of India to protect the Gupta era style wood carvings.[9] According to Handa, the original plan of the temple may have been an open twin-tiered hansakara plan. The snow and weather may have led the community to add structure to protect the temple, modifying it first into a nirandhara plan of Hindu temple architecture, and therefrom to the current sandhara plan.[9]

The sanctum contains a 7th-century brass statue of Durga, locally called Lakshana Devi. She is shown with four arms, holding a trishula in one hand, a sword in another and a bell in third. Her left front hand holds the tail of the shape shifting deceptive buffalo-demon (Mahishasura). Her right foot is on the head of the buffalo-demon, as she kills the evil demon.[7][1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Alexander Cunningham translated the same inscription as, "Aum! this image of Lakshana Devi, for the increase of his own virtue, was dedicated by Meru Varmma Deva, the son of Sri Divakara Varmma Deva, the grandson of Sri Bala Varmma Deva, the great grandson of Sri Aditya Varmma Deva, of the race of Mohsunaswa, and family of Aditya. Made by Gugga."[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mulk Raj Anand (1997). Splendours of Himachal Heritage. Abhinav Publications. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-81-7017-351-9.

- ↑ George Michell (2000). Hindu Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-500-20337-8.

- 1 2 Omacanda Hāṇḍā (2001). Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Indus. pp. 136–138. ISBN 978-81-7387-115-3.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz (1955). The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. E. J. Brill. pp. 14, 59–65, 75–83.

- ↑ Ronald M. Bernier (1997). Himalayan Architecture. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 139–142. ISBN 978-0-8386-3602-2.

- 1 2 3 Bernier, Ronald M. (1983). "Tradition and Invention in Himachal Pradesh Temple Arts". Artibus Asiae. 44 (1): 65–91. doi:10.2307/3249605. JSTOR 3249605.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reports of the Archaeological Survey of India: 1878-79, Alexander Cunningham, ASI, pages 109-112,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 Laxman S. Thakur (1996). The Architectural Heritage of Himachal Pradesh: Origin and Development of Temple Styles. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 89–91, 149–150. ISBN 978-81-215-0712-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Omacanda Hāṇḍā (2001). Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Indus. pp. 138–143. ISBN 978-81-7387-115-3.

- ↑ Swati Mitra (2006). The Buddhist Trail in Himachal: A Travel Guide. Good Earth. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-81-87780-33-5.

- ↑ India Handbook. Trade & Travel. 2000. pp. 518–526. ISBN 9780844248417.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz (1955). The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. Brill Academic. pp. 18–21, 75–83.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz (1955). The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. Brill Academic. pp. 73–79 with Plates I, II, VI and IX.

- ↑ J. Ph. Vogel (1911), Antiquities of Chamba State, Archaeological Survey of India, Vol. XXXVI, Superintendent Government Printing, India

- ↑ Jean Philippe Vogel; Bahadur Chand Chhabra (1994). Antiquities of Chamba State: Inscriptions of the pre-Muhammadan period. Director General, Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Jean Philippe Vogel; Bahadur Chand Chhabra (1994). Antiquities of Chamba State: Inscriptions of the pre-Muhammadan period. Director General, Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 7–8, 97–98, 138.

- 1 2 Mian Goverdhan Singh (1999). Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh. Indus. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-81-7387-094-1.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz (1955). The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. Brill Academic. pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Omacanda Hāṇḍā (2001). Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Indus. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-81-7387-115-3.