| Lalitaditya Muktapida | |

|---|---|

| Maharaja of Kashmir | |

| Reign | r. c. 724 CE–760 CE |

| Predecessor | Tarapida |

| Successor | Kuvalayapida |

| Spouse | Kamaladevi, Chakramardika |

| Issue | Kuvalayapida, Vajraditya II |

| Dynasty | Karkoṭa |

| Father | Durlabhaka (Pratapaditya II) |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| History of Kashmir |

|---|

|

Lalitaditya alias Muktapida (IAST: Lalitāditya Muktāpīḍa; r. c. 724 CE–760 CE) was a monarch belonging to the Karkota dynasty of Kashmir region in the Indian subcontinent.

The 12th-century chronicler Kalhana characterizes Lalitaditya as a "world conqueror", crediting him with extensive conquests and miraculous powers across India and Central Asia. However, Kalhana's account is not supported by contemporary records; for example, the Tang dynasty chronicles present him as a vassal of the Tang emperor. Nonetheless, he is accepted as the most powerful king of his dynasty.

He commissioned a number of shrines in Kashmir, including the now-ruined Martand Sun Temple. He also established several towns, including a new capital at Parihasapura.

Background

The main source of information about Lalitaditya is Rajatarangini, a chronicle of the rulers of Kashmir, by the 12th century Kashmiri writer Kalhana. Lalitaditya also finds a brief mention in the New Book of Tang (Xin Tang shu), a record of the Tang dynasty of China. This text mentions him as "Mu-to-pi" or "Muduobi" (a variation of Muktapida).[1][2] The 11th century Persian chronicler Al-Biruni mentions a Kashmiri king called Muttai, who was most probably Lalitaditya ("Muttai" being derived from the Apabhramsha form of "Muktapida").[1]

The Rajatarangini names Lalitaditya as the youngest son of the Karkota king Durlabhaka (alias Pratapaditya) and queen Narendraprabha. His mother Narendraprabha was previously married to a foreign merchant settled in Kashmir. He had two elder brothers named Chandrapida (alias Vajraditya) and Tarapida (alias Udayaditya), who preceded him as the rulers of Kashmir.[3]

Kalhana states that Lalitaditya's reign lasted for 36 years, 7 months and 11 days.[4] He suggests that Lalitaditya ruled during 724-761 CE.[1] However, this is not correct, as Lalitaditya's predecessor is known to have sent an embassy to the Tang capital Chang'an in 720 CE.[5] This predecessor, mentioned as "Tianmu" in the Tang records, was probably Tarapida, although some scholars have identified him as Chandrapida.[6] Modern historians date Lalitaditya's reign to c. 724/5 - c. 760 CE.[7]

Lalitaditya claimed to be a descendant of the mythical Nāga king Karkotaka.[8]

Military career

Kalhana's account

Kalhana describes Lalitaditya as a universal monarch, who spent most of his life in military expeditions. He gives the following account of Lalitaditya's career:[9]

Lalitaditya invaded the Antarvedi country, whose capital was located at Gadhipura (Kanyakubja). The defending king Yashovarman submitted to him after a long war and offered a peace treaty. Yashovarman drew up a document outlining the terms of this treaty, titled "The treaty of Yashovarman and Lalitaditya". Lalitaditya's minister Mitrasharman objected to this title, and insisted that Lalitaditya's name appear before Yashovarman's name in the title. Lalitaditya's generals, who were uneasy about the long duration of the war, blamed Mitrasharman for delaying the treaty. But Lalitaditya himself was pleased with Mitrasharman: he broke off the peace negotiations, and "uprooted" Yashovarman. As a result of this defeat, Yashovarman, who had been served by the court poets such as Vakpati and Bhavabhuti, himself became a panegyrist of Lalitaditya. The land of Kanyakubja, located between the Yamuna river and the Kalika river (possibly modern Kali Nadi), came under Lalitaditya's control.[10]

Lalitaditya instituted five new offices, which were occupied by Shahi and other princes.[11] After consolidating power in Kanyakubja, Lalitaditya proceeded to the eastern ocean, just like the Ganges river flows from the Himalayas to the eastern ocean. During this expedition, the elephants in this army saw the land of their birth. Lalitaditya reached Kalinga and Gauda, and a number of elephants joined his army from Gauda.[12]

From the eastern sea-shore, Lalitaditya proceeded to the southern region, where the Karnatas bowed down before him. The sovereign of Dakshinapatha at this time was a Karnata queen named Ratta. She had constructed obstacle-free roads over the Vindhya mountains, and was as powerful as the goddess Vindhyavasini (Durga). Even a powerful figure like her bowed down to Lalitaditya. In the south, Lalitaditya's soldiers forgot their fatigue, as they sipped wine of the coconut trees and enjoyed the breeze on the banks of the Kaveri river.[13] The snakes dropping from the sandalwood trees on Chandanadri (the Malaya mountains) appeared like curved swords falling from the arms because of the fear of an attack by Lalitaditya. The Kashmiri king crossed the oceans via the islands, as one crosses a rivulet by stepping over stones.[13]

After crossing the ocean, Lalitaditya reached the seven Konkanas.[14] Dvaraka, located on the western sea shore, inspired Lalitaditya's soldiers with desire [to enter that city].[14] Lalitaditya's elephant army then marched into Avanti. The dust raised by his army's crossing of Vindhya mountain made the Vindhya appear red with anger. In Avanti, the tusks of his elephants were split only by the moonlight falling on the diadem of Mahakala. (This is a reference to the traditional myth that the moonlight can split the elephant tusks).[14]

Having defeated most of the other kings, Lalitaditya proceeded from Avanti to Uttarapatha (the northern region), where he fought with several mighty kings.[14] His army emptied the Kamboja stables of horses (a reference to the Kamboja country's reputation for good-quality horses). The resulting darkness made them appear as if they were filled with black buffaloes instead.[14] The Tuhkharas fled to mountain ranges on Lalitaditya's approach, leaving behind their horses.[14] He also defeated Mummuni three times in a battle, and made the Bhauttas very anxious. Lalitaditya was too dignified to tolerate the wine-drinking Daradas.[15]

When Lalitaditya approached the deserted town of Pragjyotisha, he saw the smoke arising from the black aloes burning in the forests.[15] In Valukambudhi ("sea of sand"), where the mirage resulted in an illusion of water, Lalitaditya's elephants appeared like large crocodiles.[16] The women of Stri-rajya (literally "women's kingdom") melted the hearts of Lalitaditya's warriors by showing their "high breasts". When the trembling queen of Strirajya met Lalitaditya, no one could determine whether the emotion displayed by her was the terror or the desire of love.[16] On Lalitaditya's approach, the Uttarakurus took shelter in the trees just like snakes hide in holes on seeing a Garuda.[16]

Lalitaditya returned to Kashmir with the immense wealth obtained from his conquests. He appointed his attendants as the kings of Jalaṃdhara, Lohara and other countries. By Lalitaditya's order, the Turushkas and Dakshinatyas in his kingdom had to display a badge of shame. The Turushkas had to carry their arms at their backs and shave half of their heads, to mark their bondage.[16] The Dakshinatyas had to wear a tail that swept the ground, to signify their similarity to beasts.[17]

Lalitaditya established several cities and shrines during his stay in Kashmir. Once, he invaded and conquered the kingdom of Sikata-sindhu ("Ocean of the Sand"), after crossing a massive wasteland (see miraculous powers section below).[18] After some time, he marched towards the "boundless regions of the north", because he was curious to visit the lands where no one had reached before. During this campaign, he had several adventures with demons sent by the deity Kubera to test his power.[19]

When Lalitaditya's ministers did not receive any news about him for several days, they sent a messenger to find him.[19] The messenger came back with the news that the king did not wish to return, having decided to remain engaged in military conquests until his death. In his message, Lalitaditya provided political wisdom on how to govern the kingdom, and asked for his elder son Kuvalayapida to be appointed as his successor.[20]

Later, some people reported that Lalitaditya died in the Aryanaka country, as a result of excessive out-of-season snowfall.[4] Others reported he immolated himself in a dire situation, because he wanted to die while he remained a great king.[21]

General historicity of Kalhana's account

.jpg.webp)

M. A. Stein (1900), who first translated Rajatarangini into English, accepted Lalitaditya's subjugation of Yashovarman as a historical fact. However, he rejected the subsequent victories described by Kalhana as "manifestly legendary", given the absence of historical details.[22] According to him, the kingdom of Kashmir did not have manpower or resources to carry out such extensive campaigns.[23]

According to historian C. V. Vaidya (1861–1938), Kalhana's account is corroborated by the 13th century text Chach Nama. A letter in this text, addressed by Raja Dahir to Muhammad bin Qasim, mentions "the King of Kashmir on whose royal threshold the other rulers of Hind had placed their heads, who sways the whole of Hind, even the countries of Makran and Turan, whose chains a great many noblemen and grandees have willingly placed on their knees and against whom no human being can stand." This letter is stated to have been written in 712 CE, so Vaidya theorizes that Lalitaditya's conquests must have occurred during 700-712 CE.[24]

Later, art historian Hermann Goetz (1969) devised a historical reconstruction supporting Kalhana's account, although he admitted that "this reconstruction cannot claim to be more than a working theory trying plausibly to interconnect the sparse and uncertain data". Goetz argued that Kalhana's account of Lalitaditya's military exploits is not only probable, but also supported by other evidence.[25] According to Goetz, Lalitaditya's extensive conquests were possible because the other contemporary kingdoms in the region had been weakened by foreign invasions and wars.[26] In addition, Goetz speculated that Lalitaditya managed to create a powerful army as a result of superior China-influenced military organization, administrative set-up and weaponry.[27] Goetz identified several persons mentioned in Kalhana's account as historical figures, and argued that a distant writer like Kalhana could not have invented such historical persons.[27]

André Wink (2002) described Goetz' theory as convincing,[22] but Ronald M. Davidson (2012) dismisses Wink's affirmation of Goetz's analysis as uncritical. Davidson rejects the argument that the conquests described by Kalhana must have been real, because Kalhana could not have invented historical persons. In his support, Davidson presents the example of the Nilamata Purana, which is one of Kalhana's sources for Rajatarangini, and which ascribes fictional events to historical persons. He argues that Kalhana's dubious sources could have fabricated a conquest of known parties.[28] Davidson points out that Yashovarman's court poet Vakpati credits him with similar conquests in Gaudavaho, according to which Yashovarman conquered not only eastern and southern India, but also defeated the king of Persia. Davidson dismisses both Gaudavaho and Rajatarangini as poetic boast, describing Kalhana's account as "Kashmiri boosterism". He, however, believes that Kalhana's claims might be closer to the truth than Vakpati's claims. According to Davidson, Lalitaditya launched his attack in 733 CE, advanced up to Magadha in the east, and then returned to Kashmir in 747 CE.[29]

Tansen Sen (2004) similarly rejects the claims about Lalitaditya's conquest of Hindu Kush-Pamir region, based on numismatic evidence and contemporary records other than Rajatarangini. According to him, Lalitaditya provided military and logistical support to the Tang campaigns against Tibetans, and the success of these campaigns later led to Kashmiri legends describing him as a great conqueror.[30]

Shyam Manohar Mishra (1977) points out that Lalitaditya's achievements "must have been coloured and exaggerated by the popular imagination" by the time of Kalhana, who lived four centuries after Lalitaditya. This is evident from the fact that Kalhana ascribes miraculous powers to Lalitaditya.[31] According to Susan L. Huntington (1997), Lalitaditya's campaigns were probably "massive raiding and looting expeditions rather than true conquests".[32]

Detailed analysis of Kalhana's account

Afghanistan and Punjab

Goetz theorizes that Lalitaditya had captured Punjab, Afghanistan, and western part of the Central Asian highlands before embarking upon his campaign in central India.[33] He dates Lalitaditya's conquest of Afghanistan before 730 CE, and presents the following arguments in his support:[34]

- There is a gigantic gilt copper Buddha statue beside Lalitaditya's chaitya at Parihasapura. It appears to be inspired by the Bamiyan Buddha statue.[35] At the same time, there is no influence from the Gupta art, which was popular in Yashovarman's territory.[5]

- Before Lalitaditya, Afghanistan was controlled by Turkic Shahi "princelings", who were under nominal Chinese control after the fall of the Sasanian Empire. After Lalitaditya, Afghanistan came under the control of the Hindu Shahi dynasty of Lalliya.[35]

- The Muslims from the west could not advance beyond Multan in Punjab during this period. While the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate was a factor in this, it also appears that there was an Indian empire powerful enough to offer resistance to the Caliphite armies.[35]

Tansen Sen (2004) criticizes Goetz' theory, based on numismatic evidence and other contemporary records. These sources suggest that Kapisa and Zabulistan regions in present-day Afghanistan were under control of the independent Turkic Shahi rulers. The records of the Tang dynasty, whose rulers received regular embassies from the Turkic Shahis, testify to their independent status.[36] According to Sen, the Karkota kingdom had peaceful relations with these Turkic neighbours: this very fact may have enabled Lalitaditya to leave Kashmir and lead troops to central and eastern India.[37]

Yashovarman

Lalitaditya's victory over Yashovarman appears to be historically true.[38] Historical evidence suggests that the two kings were immediate neighbours before their conflict: Lalitaditya's empire extended up to present-day Punjab in the south-east, while Yashovarman's north-eastern frontier included parts of present-day Haryana.[39] The discovery of some coins bearing the legend Shri-Pratapa in present-day Uttar Pradesh is also considered as an evidence of Lalitaditya's success in this region (as Pratapaditya was the name of Lalitaditya's father).[40] Abhinavagupta's ancestor Atrigupta, a scholar who originally lived in Yashovarman's territory, was brought to Kashmir by Lalitaditya.[41] This may have happened during Lalitaditya's invasion.[42]

However, Kalhana's account of this victory over Yashovarman cannot be taken at the face value.[31] According to historian Shyam Manohar Mishra (1977), the earlier historians have overrated Lalitaditya's success against Yashovarman: the defeated king acknowledged Lalitaditya's suzerainty for a short period, but became practically independent when Lalitaditya became engaged in other conflicts.[43]

The date of the conflict between the two kings is not certain. The Annals of the Tang dynasty suggest that Lalitaditya and a Central Indian king had fought against Tibet as allies.[1] Assuming that this central Indian king was Yashovarman (after his subjugation by Lalitaditya), M. A. Stein dated Lalitaditya's conquest to sometime before 736 CE.[44] However, Mishra interprets the Tang records differently to theorize that Lalitaditya and Yashovarman were allies at least until 736 CE.[45] According to Mishra, the conflict between Lalitaditya and Yashovarman took place after 736 CE, and before Yashovarman's death in 749-753 CE.[46]

German Indologist Hermann Jacobi dated Lalitaditya's invasion of Kannauj to 14 August 733 CE, a date that was accepted by several later historians. This theory is based on the Gaudavaho, a text composed by Yashovarman's court poet Vakpati. This text describes a solar eclipse (an inauspicious omen), which Jacobi considers to be an allusion to Yashovarman's defeat.[47] Jacobi also bases his conclusion on a subsequent verse, which he translates as "The corner of his [Yashovarman's] eye-brow became twisted on account of the shaking of his [kingly] position."[48] Assuming 733 CE as the date of Lalitaditya's victory, Goetz dated the beginning of the conflict to 730 CE or earlier.[34]

Shyam Manohar Mishra rejects Jacobi's conclusion, pointing out that the 733 CE solar eclipse could be seen from several other regions (including Kashmir), and there is no evidence linking it to Yashovarman's defeat.[49] In fact, the surrounding verses in the poem make it clear that the verse about solar eclipse does not signify any debacle for Yashovarman.[50] Moreover, Jacobi has mistranslated the subsequent verse, which actually states that if Yashovarman's order was defied, he twisted his eyebrow (became angry), resulting in great calamities in the realms of those who defied the order.[51]

Eastern India

According to Goetz, Lalitaditya conquered present-day Bihar, Bengal and Odisha by 735-736 CE.[34] Based on Kalhana's account, Goetz theorized that Lalitaditya marched to Gauda after defeating Yashovarman. There, he defeated the Later Gupta ruler Jivitagupta, and then advanced up to the Bay of Bengal through present-day Odisha.[5] Goetz further theorized that Yashovarman supported Lalitaditya in these campaigns as a vassal. In the poem Gaudavaho, Yashovarman's courtier Vakpati credits him with victories in eastern and southern India. The Rajatarangini makes similar claims for Lalitaditya. According to Goetz, the invasion routes described in both these texts are "practically identical".[52] He, therefore, concludes that Yashovarman participated in Lalitaditya's wars as a vassal. Goetz argues that Gaudavaho fails to mention this, because Yashovarman's court poet wanted to whitewash his master's vassal status. Gaudavaho mentions that Yashovarman visited the Mandara mountain. According to Goetz, this is the poet's way of hiding Yashovarman's visit to Lalitaditya's court, which was located in the mountainous region.[53]

Shyam Manohar Mishra (1977) rejects Goetz theory, pointing out that no sources (including Rajatarangini and Gaudavaho) suggest that Yashovarman participated in Lalitaditya's subsequent campaigns as a vassal.[54] Mishra believes that the conflict between the two kings happened after Yashovarman's successful campaign, which must have "evoked the jealousy and concern of Lalitaditya".[39]

Southern India

The term "Ratta" in Kalhana's account appears to be a reference to the Rashtrakutas, who ruled the Karnata region. The term "Vindhyas" here cannot refer to the present-day Vindhya mountains: it is probably used for poetic effect, to compare Queen Ratta to the goddess Vindhyavasini (who is said to reside in the Vindhyan region).[13]

Goetz identified Kalhana's Queen Ratta with Bhavagana, who was a wife of the Rashtrakuta king Indra I. Goetz speculates that she acted as a queen regent for her son Dantidurga after Indra's death, but her rule was threatened by her brother-in-law Krishna I.[52] As a result, she appealed Lalitaditya for help, who arrived in Deccan and fought on her side.[5] Goetz further theorized that Yashovarman and Jivitagupta participated in this campaign as his vassals. His arguments include:[53]

- Gaudavaho claims that Yashovarman also invaded Deccan. According to Goetz, had Yashovarman had invaded Deccan alone, this invasion would have taken place before his debacle against Lalitaditya, that is, sometime before 730 CE. But Vijayaditya, the contemporary ruler of Deccan, was a very powerful king. Therefore, Yashovarman could have invaded Deccan only as part of a more powerful force led by Lalitaditya.[53]

- Bhavagana was a Chalukya princess before marriage, and therefore, her Chalukya relatives could have allowed Lalitaditya to pass through northern Deccan, enabling him to easily invade the territory controlled by Krishna.[52]

- Goetz also assumes that Dantidurga threw off Lalitaditya's vassalage after the Kashmiri king returned to the north. In his support, he cites Dantidurga's Samangad inscription. According to Goetz, this record claims that Dantidurga repulsed "an invasion by the combined rulers of Sindh, Malwa and Kosala".[52] The contemporary Arab ruler of Sindh would not have allied with the Hindu rulers of Malwa or Kosala. Therefore, this invasion can only refer to Dantidurga's successes against the forces of Lalitaditya and his vassals (Yashovarman and Jivitagupta). Malwa here can be interpreted as Yashovarman's frontier territory or Jivitagputa's paternal territory. Kosala here may refer to the Kosala region (in present-day Uttar Pradesh) controlled by Yashovarman, or the Dakshina Kosala region which was located at the south-western frontier of Gauda. According to Goetz, the term "Sindh" has been used to describe Kashmir in Pratihara inscriptions.[55]

Western India

Goetz identified Kalhana's "Mummuni" with the contemporary Shilahara ruler of Konkan. Although no contemporary Shilahara king by this name is known, there was an 11th-century Shilahara king with the same name. Goetz speculates Lalitaditya's Shilahara contemporary was also called Mummuni: his name must have been removed from the Shilahara family records because of his humiliating defeat against Lalitaditya.[52]

Kalhana mentions that Kayya, the king of Lata, built a temple in Kashmir during Lalitaditya's reign. Goetz identifies Kayya with Karka II, the Rashtrakuta governor of the Lata region (present-day southern Gujarat). Although Kalhana doesn't mention Kayya in connection with Lalitaditya's campaign, Goetz argues that a ruler of Lata would not have gone all the way to Kashmir to build a temple.[27] Goetz assumes that he was taken there as a vassal.[52] However, Karka's presence in Gujarat is attested by a 757 CE grant inscription. Goetz theorizes that Lalitaditya must have died before this year, and Karka must have returned to Gujarat after his death.[56]

According to Goetz, Lalitaditya invaded Kathiawar (in present-day Gujarat) between 740 and 746 CE. By this time, the local rulers Maitrakas had already been subjugated by the Chalukyas, which would have allowed Lalitaditya to establish his hegemony in the region.[56]

Return to Kashmir

According to Goetz, Lalitaditya returned to Kashmir, when the Tibetan king Me Agtsom invaded Kashmir around 747 CE. Goetz theorizes that during this return journey, Lalitaditya passed through Ujjain, Chittorgarh, Marwar and Thanesar.[56] He also speculated that the legendary Guhila ruler Bappa Rawal of Chittorgarh served Lalitaditya as a vassal, and died fighting in the Kashmiri king's Central Asian campaigns.[25]

Goetz goes on to connect Lalitaditya to the mythological Agnikula legend, according to which some later regional dynasties originated from a fire pit during a sacrificial ceremony at Mount Abu. Goetz speculated that Lalitaditya wanted to leave behind some governors before marching against Tibetans; therefore, he conducted a ceremony to induct the "various Gurjara tribes" into the Hindu political system as Kshatriyas (recognized warriors).[25]

Hindu Kush-Pamir region

According to Goetz, after returning to Kashmir, Lalitaditya not only repulsed the Tibetans but also invaded the Tarim Basin.[25] Goetz identified Kalhana's "sea of sand" as the desert areas of Turkestan and Tibet.[33] Goetz speculated that in 755-756 CE, Lalitaditya invaded the towns in Taklamakan and Gobi deserts, and marched to Kucha and Turfan, after the Tang power declined as a result of the An Lushan Rebellion.[57]

Goetz' interpretation was widely accepted and cited by the subsequent scholars.[58] However, Tansen Sen (2004) rejects Goetz' assessment of Lalitaditya's exploits as exaggerated, based on his study of the contemporary Chinese and Tibetan records, as well as numismatic evidence. Sen also analyzed the writings of the Korean monk Hyecho (who visited Kashmir in 725 CE, at the beginning of Lalitaditya's reign) and the Chinese monk Wukon (who stayed in Kashmir for four years during c. 753-763 CE, after Lalitaditya's death). None of these sources support Goetz' assertion that Lalitaditya managed to establish a vast Kashmiri empire in the Hindu Kush-Pamir region, or that he marched across the Taklamakan desert.[59] Historical evidence indicates that the Tang dynasty retained control of the oasis states in the desert region until the early 780s CE, when the Tibetans established their dominance.[57] There is no evidence of Lalitaditya's march to Pamir region either: the Old Tibetan Annals establish that a number of northern Pamir rulers sent envoys to pay homage to the Tibetan court in 756-757 CE. This suggests that this area was under control of the Tibetans, whose records do not mention any conflict with Kashmir.[57]

Goetz considered the Tokharian origin of Lalitaditya's minister Chankuna (IAST: Caṇkuṇa) as an evidence of the Kashmiri hegemony over the Turkic kingdoms. According to Kalhana, Lalitaditya brought Chankuna to Kashmir from the Tuhkhara land (Tokharistan).[60] "Chankuna" is believed to be a Sanskrit transcription of the Chinese title jiangjun ("military general"). Goetz speculated that Chankuna was a Tokharian general in the Chinese army, and introduced the Chinese warfare techniques in Kashmir, which enhanced Lalitaditya's military campaigns. Sen criticizes this theory, pointing out that Kalhana's writings acclaim Chankuna for magical powers, not military expertise. Moreover, the Tokharian origin of Chankuna cannot be considered as concrete evidence of Kashmiri control over southern Hindu Kush region.[61]

According to Sen's theory, the Karkotas achieved successes against Tibetans as part of an alliance with the Tang dynasty. These successes led to development of legends about Kashmir's dominance in the southern Hindu Kush-Pamir region. Based on these legends, four centuries later, Kalhana characterized Lalitaditya as a world-conqueror.[62]

Sen points out that according to the New Book of Tang, Lalitaditya's envoy came to the Tang court with a letter in March–April 933 CE. In this letter, Lalitaditya presents himself as a Tang vassal who had "submitted to the Heavenly Qaghan". Lalitaditya further explains that the Tibetans had distressed him and another king of Central India by blocking the five great routes. But the two Indian kings had managed to defeat the Tibetans. Finally, Lalitaditya requests the Tang army to arrive at Palur (present-day Gilgit-Baltistan), offering to set up a camp for them beside the Mahapadma lake (modern Wular Lake). He promises to supply provisions for the Tang army, even if it numbered as large as 200,000.[63]

According to the Tang records, the Tang emperor was pleased by Lalitaditya's offer, and bestowed the title of "King" upon Lalitaditya.[63][64] In the subsequent years, Tang forces fought with the Tibetans over Little Palur (present-day Gilgit Valley). The Tangs finally captured it in 747 CE, after three failed attempts.[65] Lalitaditya's Kashmir seems to have played a significant role in these conflicts.[66]

The Tang records also mention that an envoy from Tokharistan visited the Tang court in 749 CE, and requested it to renew its alliance with Kashmir by sending the Kashmir king precious gifts. The envoy's objective was to enlist the Tang help against the Tibet's ally Kashgar. The envoy pointed out that the ruler of Kashmir respected the Chinese, and had a large cavalry and infantry. The Chinese accepted the envoy's recommendation, and in 750 CE, the Tang general Gao Xianzhi conquered Kashgar.[66] These records suggest that Lalitaditya provided military assistance and logistical support to Gao Xianzhi's forces in this campaign.[67]

Tansen Sen believes that the "Bhauttas" (Tibetans) and the "Daradas" mentioned by Kalhana may have been Lalitaditya's rivals in these 747 CE and 750 CE campaigns.[67]

Personal life

Lalitaditya was succeeded by his sons: first Kuvalayapida and then Vajraditya. Kuvalayapida was a son of queen Kamaladevi, while Vajraditya was a son of Chakramardika. Vajraditya was succeeded by his sons Prthivyapida and Samgramapida.[68]

Public works

Cities and towns

Kalhana states that Lalitaditya established the following cities and towns:

- Sunishchita-pura, when he decided (sunishchita) to conquer the world[17]

- Darpita-pura, when he felt proud[17]

- Phala-pura, when he received fruit (phala). M. A. Stein located Phalapura near Parihasapura and the confluence of Vitasta and Sindhu.[17]

- Parnotsa, when he took a leaf (parna). Stein identified this town with modern Poonch.[17]

- Lokapunya town, which is identified with the area near the Lokabhavana spring near modern Larikpur.[69]

- Parihasapura, which was better than the residence of Indra.[70] This city became Lalitaditya's residence for a brief period, while Srinagara continued to serve as the other capital. Parihasapura had been deserted and ruined by the time of Kalhana.[71]

- Several towns in salty wastelands, to ensure that anyone suffering from thirst could find water to drink.[72]

Kalhana also mentions that while Lalitaditya was away from his kingdom, his architect built a town called Lalitapura after him, but this angered Lalitaditya. One theory identifies this place with the modern Lethipora (or Latpor).[17] Lalitaditya's wife Chakramardika is also said to have built the city of Chakrapura with 7,000 houses.[71]

According to Kalhana, Lalitaditya once ordered the Pravarapura town to be burnt down, while in a drunken stupor. The town had been built by an earlier king named Pravarasena, and Lalitaditya did not want another town as beautiful as Parihasapura to exist. However, when Lalitaditya came to his senses, he regretted his decision.[73] He was relieved when his ministers informed him that they had not actually carried out his order. He was pleased with his ministers' wise decision, and instructed them to similarly ignore his commands whenever he was drunk.[74]

Shrines

Kalhana states that Lalitaditya constructed a shrine in every town, village, river, sea and island.[17] His wives, ministers and attendants consecrated hundreds of images in these temples.[75] Lalitaditya placed idols of the deities' attendants, made of gold and silver, in these shrines.[75]

Vishnu shrines

According to Kalhana, Lalitaditya commissioned shrines dedicated to various aspects of Vishnu, including Keshava, Nṛhari and Muktasvamin:

- Built a shrine of Keshava in Darpitapura[17]

- Installed an image of Nṛhari in Strirajya. This image was suspended in air by fixing magnets above and below it.[17]

- Built the Muktasvamin shrine at Hushkapura (modern Ushkur).[76]

- Made an offering to Vishnu after building the Lokapunya town.[69]

- Installed several images of Vishnu and his aspects in Parihasapura:[77]

- a silver image of Parihasa-Keshava (made of 84,000 of palas; the pala is ancient unit equivalent to 4 tolakas)

- a gold image of Mukta-Keshava (made of 84,000 tolakas of gold)

- a gold image of Maha-Varaha

- a silver image of Govardhana-Dhara

- Raised a pillar which measured 54 hands in height, and had an image of Garuda (Vishnu's vahana) at the top.[70]

Others also constructed Vishnu shrines during his reign:

- Lalitaditya's queen Kamalavati established Kamalahatta (a market), where she installed a silver idol of Kamala-Keshava.[75]

- Kayya, the king of Lata, built the famous shrine of Kayyasvamin.[75]

Kalhana also mentions a legend describing the discovery of two ancient idols: Lalitaditya, who was a skilled horse-rider, once took an untrained horse to a wasteland alone.[78] There he saw some lovely dancing girls, who said that they belonged to a temple in the Suravardhamana village located in the wasteland. Next, day the king had the wasteland dug up. This excavation resulted in discovery of two decayed temples, each with an idol of Keshava. The inscriptions on these idols indicated that they had been made by Rama and Lakshmana. The king brought these idols to Parihasapura, where he erected a stone shrine beside the Parihasa-Keshava temple. He installed the Rama-svamin (Rama's idol) in this stone building. His queen Chakramardika installed the Lakshmana-svamin (Lakshmana's idol) beside her Chakreshvara shrine.[79]

According to Kalhana, the Rama-svamin idol was later destroyed by the men of Gauda to avenge their king's assassination by Lalitaditya. The Gauda king had come to Kashmir on a visit, and the idol of Parihasa-Keshava had been made a surety for his safety. Despite this, Lalitaditya had him assassinated in Trigrami (modern Trigam). To avenge their king's treacherous murder, his servants came from Gauda to Kashmir, determined to destroy Lalitaditya's beloved Parihasa-Keshava idol. They entered Kashmir under the pretext of visiting the shrine of the goddess Sharada. Lalitaditya was away from Parihasapura at that time, and the attendants of the Parihasa-Keshava temple closed its gates to prevent the Gauda men from entering the shrine.[74] The Gauda men mistook the Ramasvamin idol for the Parihasa-Keshava idol, and destroyed it, before being killed by Lalitaditya's soldiers.[19]

Buddhist shrines

Kalhana also credits Lalitaditya with building the following Buddhist shrines:

- Built a large vihara with stupa at Hushkapura (modern Ushkur, where the remains of a stupa and a Shiva shrine have been discovered). The Chinese pilgrim Ou-Kong mentions the "Moung-ti" vihara among his list of Kashmiri monasteries; Stein identifies this vihara with the Ushkur site, and theorizes that "Moung-ti" is the Chinese transcription of "Mukta".[76]

- Built the Rajavihara with a large chatuh-shala (square), a large chaitya, and a large image of the Jina (the Buddha).[70]

- Erected a very high statue of the Brhadbuddha ("Great Buddha"), made of 84,000 prasthas of copper (the prastha is an ancient unit equivalent to 64 tolakas).[77]

The king's subjects are also said to have built Buddhist shrines:

- Kayya, the king of Lata, also built the famous Kayya-vihara, which later became the residence of the bhikshu Sarvajnamitra.[75]

- Chankuna established Chankuna-vihara (IAST: Cankunavihara), which included a tall stupa and golden image of the Jinas.[75]

- Chankuna also established another vihara (with a chaitya) in Srinagara.[71]

- Chankuna's son-in-law and physician Ishanachandra also built a vihara after obtaining wealth through the blessings of Takshaka.[71]

Shiva shrines

According to Kalhana:

- Lalitaditya took 1 crore from Bhutesha (shrine of Shiva) while embarking on world conquest, and gave 11 crores as expiatory offering upon his return to Kashmir. He constructed the Jyeshtharudra stone temple dedicated to Shiva, and granted land and villages to the shrine. The Bhutesha shrine is identified with modern Wangath (Bhutser or Buthser).[76]

- His minister Mitrasharman installed a Shiva linga called Mitreshvara.[75]

- A teacher named Bhappata built the linga called Bhappateshvara.[71]

- Other people also built several lingas, known as Rakchatesha.[71]

Surya shrines

Kalhana mentions that Lalitaditya built a shrine of Aditya (the sun god) in Lalitapura, and granted the land of Kanyakubja and its villages to this shrine.[17] In addition, he commissioned the Martanda sun temple and the surrounding town.[80]

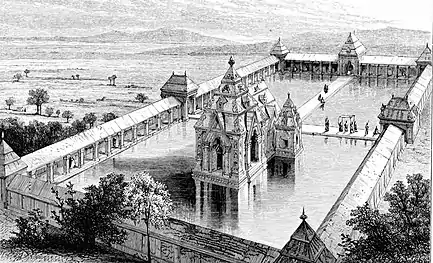

- Martand Sun Temple

Ruins in c. 1870

Ruins in c. 1870 Restored impression by J. Duguid (1870–73)

Restored impression by J. Duguid (1870–73).jpg.webp) Ruins in summer of 2011

Ruins in summer of 2011.jpg.webp) Ruins in winter of 2012

Ruins in winter of 2012

Other activities

Kalhana states that Lalitaditya made an arrangement at Chakradhara to distribute the Vitasta river water to several villages using a series of water wheels. Chakradhara is identified with modern Tsakdar Udar plateau near Bijbehara.[81] Ishanadevi, a wife of his minister Chankuna, constructed a water-well whose pure water cured the sick.[71]

According to Kalhana, Lalitaditya collected wise men from different countries, just "as the wind collects masses of full-blown flowers". For example, from Tuhkhara, he brought Chankuna (IAST: Caṇkuṇa), who had great qualities.[72][60]

Kalhana states that Lalitaditya started the Sahasra-bhakta festival at Parihasapura. During this festival, he distributed 100,001 food dishes beside dakshinas (donations).[72] The 11th century Persian writer Al-Biruni states that the people of Kashmir organized an annual festival on the second day of the Chaitra month to celebrate their past king Muttai's alleged victory over the Turks. This Muttai can be identified with "Muktapida", that is, Lalitaditya. According to Al-Biruni, Kashmiris claimed that Muttai as well as most of the other Kashmiri kings "ruled over the whole world". Al-Biruni dismissed these claims as lies because of chronological inconsistencies.[1]

Alleged miraculous powers

Kalhana declares that Lalitaditya's commands were not disobeyed even by the gods.[71] Once, while encamped on the shores of the eastern ocean in the cold weather, Lalitaditya ordered kapittha fruits to be brought to him. His attendants were perplexed, as this fruit was not common in the given season and place. But then, Indra's divine messenger brought these fruits to him from the heaven. The messenger explained to him that in his previous birth, he offered his own food and water to a starving Brahmin during a famine. As a result of this good deed, Lalitaditya became entitled to a hundred wishes in the heaven. For example, the king could make streams of sweet water appear in deserts at his mere wish. The messenger cautioned Lalitaditya that he had few wishes left, and therefore, he should not waste these wishes on frivolous requests such as ordering a fruit.[82]

Kalhana also claims that Lalitaditya's minister Chankuna was a brother of the magician Kanakavarsha (literally "the one who rains gold"). He produced gold in the king's treasury using his magic powers. Once the king's army was stranded in the Panchanada country (identified with Punjab), because the local streams had "united" and could not be crossed. Chankuna magically parted the waters by throwing a mani (gem) into the streams, enabling the king's army to cross the waters. He then retrieved his mani by using another mani, and the streams were united again.[72] The king requested these two manis from Chankuna, offering anything else in return. Chankuna asked for an idol of Sugata (Buddha), which had been brought to Kashmir from Magadha on an elephant. The king fulfilled this demand, and Chankuna placed the idol in his vihara. This image still existed in the time of Kalhana, and according to him, the metal bands fastened around it proved that it was once fixed on an elephant.[78]

Kalhana also claims that Lalitaditya made several streams appear by pushing his spear (kuntavahini) into the ground.[73] Narrating one such incident, he states that one day, when Lalitaditya was engaged in the world conquest, a wounded man came to him. The man, whose limbs and nose had been chopped off, introduced himself as a minister of the rival king of Sikata-sindhu ("Ocean of the Sand"). He said that he had been punished for advising his king to accept Lalitaditya's suzerainty. Lalitaditya promised to punish the rival king, and had the wounded minister restored to health under his care. The minister then encouraged Lalitaditya to march to the Sikata-sindhu country through a shortcut, and led his army to a wasteland without water.[83] When Lalitaditya's army was on the verge of dying of thirst, the minister revealed that this was all a set-up: he was actually loyal to the rival king and intended to misguide Lalitaditya and his army to their death. Lalitaditya announced that he was impressed with the minister's loyalty to his own master, but declared that his plan would not be successful. The Kashmiri king then put his sword into the ground, making a stream come out of the water. He then reached Sikata-sindhu, where he reduced the rival king to the same pitiful condition as his limbless minister.[18]

Kalhana mentions that several other wonderful legends about Lalitaditya existed during his time, but he could not include them all in Rajatarangini because he did not want to break the flow of the narrative.[73]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 131.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 144.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 88.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 15.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 144-145.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 141.

- ↑ Meena Arora Nayak 2018, p. 53.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 130-131.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 132-134.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 133-134.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 136.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 139.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 153.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 156.

- 1 2 André Wink 2002, p. 244.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 9.

- ↑ C. V. Vaidya 1979, p. 208.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 20.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 12.

- ↑ Ronald M. Davidson 2012, p. 355.

- ↑ Ronald M. Davidson 2012, p. 46.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 141-152.

- 1 2 Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 95.

- ↑ Cynthia Packert Atherton 1997, p. 80.

- 1 2 Tansen Sen 2004, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 11.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 153.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 153-154.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 90.

- 1 2 Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 93.

- ↑ Manabendu Banerjee 2004, p. 195.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 109.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 89.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 102.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 98.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 101.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 99.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 100.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, p. 101-102.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 14.

- ↑ Shyam Manohar Mishra 1977, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Hermann Goetz 1969, pp. 14–15.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Goetz 1969, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Tansen Sen 2004, p. 154.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 Tansen Sen 2004, p. 151.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 141-142.

- 1 2 Tansen Sen 2004, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Tansen Sen (2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy and Trade. University of Hawai'i. p. 32. ISBN 9781442254732.

- ↑ Tansen Sen 2004, p. 146-147.

- 1 2 Tansen Sen 2004, p. 147.

- 1 2 Tansen Sen 2004, p. 148.

- ↑ MA Stein 2 1900, p. 269.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 141-142.

- 1 2 3 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 151.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 140.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, pp. 142–143.

- 1 2 MA Stein 1 1900, p. 147.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 148.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 141.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 140-141.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 144-146.

- ↑ MA Stein 1 1900, p. 149.

Bibliography

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th-11th Centuries. BRILL. ISBN 0-391-04173-8.

- C. V. Vaidya (1979). History of Mediaeval Hindu India: Rise of Hindu kingdoms. Cosmo.

- Cynthia Packert Atherton (1997). The Sculpture of Early Medieval Rajasthan. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10789-4.

- Hermann Goetz (1969). Studies in the History and Art of Kashmir and the Indian Himalaya. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. OCLC 586049160.

- M. A. Stein (1900). Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī: A chronicle of the kings of Kaśmīr. Vol. 1. Archibald Constable. ISBN 978-81-208-0370-1.

- M. A. Stein (1900). Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī: A chronicle of the kings of Kaśmīr. Vol. 2. Archibald Constable. ISBN 978-81-208-0370-1.

- Manabendu Banerjee (2004). Historicity in Sanskrit Historical Kāvyas. Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar. OCLC 607757485.

- Meena Arora Nayak (2018). Evil in the Mahabharata. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199091836.

- Navjivan Rastogi (1987). Introduction to the Tantrāloka. Motilal Banarsidass. OCLC 470679057.

- Ronald M. Davidson (2012). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231501026.

- Shyam Manohar Mishra (1977). Yaśovarman of Kanauj. Abhinav. OCLC 5782454.

- Tansen Sen (2004). "Kaśmīr, Tang China, and Muktāpīḍa Lalitāditya's Ascendancy over the Southern Hindukush Region". Journal of Asian History. 38 (2): 141–162. JSTOR 41933381.