This is a list of the dynasties that ruled the Roman Empire and its two succeeding counterparts, the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. Dynasties of states that had claimed legal succession from the Roman Empire are not included in this list.

List of Roman dynasties

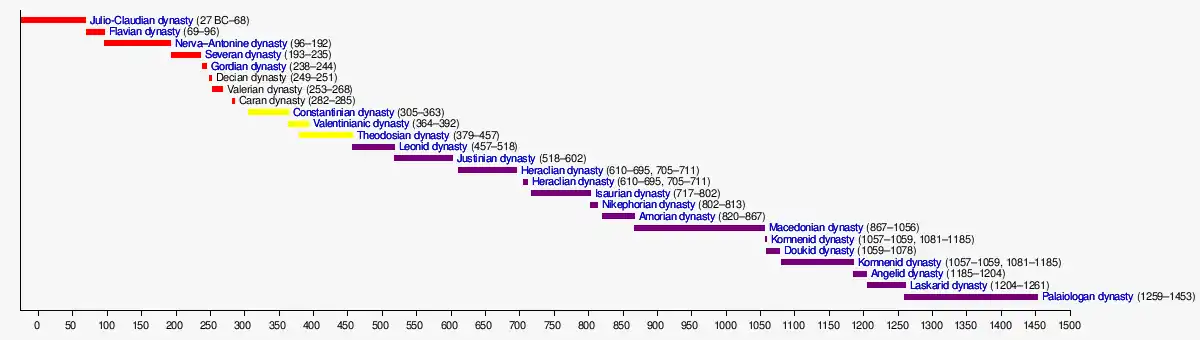

Graphical representation

See also

Notes

- ↑ As adoption was widely practiced by the upper classes, some Roman monarchs were not directly biologically related to their predecessors despite belonging to the same dynasty. For example, the second emperor of the Julio–Claudian dynasty, Tiberius, was in fact an adopted son of the dynastic founder, Augustus.

- ↑ The Nerva–Antonine dynasty is sometimes subdivided into the Nerva–Trajan dynasty and the Antonine dynasty.

- ↑ The rule of the Severan dynasty was interrupted between 217 CE and 218 CE. Caracalla was the last ruler before the interregnum. Elagabalus was the first ruler after the interregnum.

- ↑ The Constantinian dynasty is also known as the "Neo-Flavian dynasty".

- ↑ Maurice and Theodosius reigned as co-rulers.

- ↑ The rule of the Heraclian dynasty was interrupted between 695 CE and 705 CE. Justinian II was both the last ruler before the interregnum and the first ruler after the interregnum.

- ↑ Justinian II and Tiberius reigned as co-rulers.

- ↑ The Isaurian dynasty is also known as the "Syrian dynasty".

- ↑ Michael I Rangabe and Theophylact reigned as co-rulers.

- ↑ The Amorian dynasty is also known as the "Phrygian dynasty".

- ↑ The Komnenid dynasty ruled the Empire of Trebizond between 1204 CE and 1461 CE.

- ↑ The rule of the Komnenid dynasty was interrupted between 1059 CE and 1081 CE. Isaac I Komnenos was the last ruler before the interregnum. Alexios I Komnenos was the first ruler after the interregnum.

- ↑ Andronikos I Komnenos and John Komnenos reigned as co-rulers.

- ↑ In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, the Laskarid dynasty of the empire of Nicaea is traditionally accepted by historians as the legitimate continuation of the Roman Empire, mostly because in 1261 it recovered Constantinople, New Rome.[16] During the period between 1204–1261, however, there were four competing dynasties—aside from the Laskarids in Nicaea, these were the Latin emperors of the "Flanders dynasty" in Constantinople,[17] the Komnenodoukai of Epirus and the Megalokomnenoi of Trebizond—equally claiming the east Roman emperorship.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kidner, Frank; Bucur, Maria; Mathisen, Ralph; McKee, Sally; Weeks, Theodore (2013). Making Europe: The Story of the West. p. 161. ISBN 978-1111841317.

- 1 2 D'Amato, Raffaele; Frediani, Andrea (2019). Strasbourg AD 357: The victory that saved Gaul. p. 8. ISBN 9781472833969.

- 1 2 Ermatinger, James (2018). The Roman Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 233. ISBN 9781440838095.

- 1 2 Fomenko, Anatoly (2005). History: Fiction Or Science?. p. 171. ISBN 9782913621060.

- 1 2 Cowell, Frank (1961). Everyday Life in Ancient Rome. p. 199.

- 1 2 Christ, Karl (1984). The Romans: An Introduction to Their History and Civilisation. p. 184. ISBN 9780520045668.

- 1 2 Grig, Lucy; Kelly, Gavin (2015). Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity. p. 186. ISBN 9780190241087.

- 1 2 Maas, Michael (2015). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. p. 106. ISBN 9781107021754.

- 1 2 Konstam, Angus (2015). Byzantine Warship vs Arab Warship: 7th–11th centuries. p. 18. ISBN 9781472807588.

- 1 2 Flichy, Thomas (2012). Financial Crises and Renewal of Empires. p. 30. ISBN 9781291097337.

- 1 2 LePree, James; Djukic, Ljudmila (2019). The Byzantine Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 209. ISBN 9781440851476.

- 1 2 3 4 Tougher, Shaun (2009). The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society. p. 55. ISBN 9781135235710.

- 1 2 Walker, Alicia (2012). The Emperor and the World: Exotic Elements and the Imaging of Middle Byzantine Imperial Power, Ninth to Thirteenth Centuries C.E. p. 11. ISBN 9781107004771.

- 1 2 Stacton, David (1965). The World on the Last Day: The Sack of Constantinople by the Turks, May 29, 1453: Its Causes and Consequences. p. 276.

- 1 2 LePree & Djukic (2019). p. 305.

- ↑ Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. p. 734. ISBN 0804726302.

- ↑ Kanev, Nikolay (2018). Reflections of the Imperial Ideology on the Seals of the Latin Emperor Baldwin II of Courtenay. pp. 56–64.

- 1 2 Woodfin, Warren (2012). The Embodied Icon: Liturgical Vestments and Sacramental Power in Byzantium. OUP Oxford. p. xxv. ISBN 9780199592098.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.