Pilosa is an order of placental mammals. Members of this order are called pilosans, and include anteaters and sloths. They are found in South and Central America, generally in forests, though some species are found in shrublands, grasslands, and savannas. Pilosans primarily eat insects and leaves. They range in size from the silky anteater, at 36 cm (14 in) plus a 18 cm (7 in) tail, to the giant anteater, at 120 cm (47 in) plus a 90 cm (35 in) tail. No pilosans have population estimates, but the pygmy three-toed sloth is categorized as critically endangered.

The twelve extant species of Pilosa are divided into two suborders: Folivora, the sloths, and Vermilingua, the anteaters. Folivora contains two families: Bradypodidae, containing four species in one genus; and Choloepodidae, containing two species in one genus. Vermilingua also contains two families: Cyclopedidae, containing a single species, and Myrmecophagidae, containing three species in two genera. Dozens of extinct prehistoric pilosan species have been discovered, though due to ongoing research and discoveries the exact number and categorization is not fixed.[1]

Conventions

| Conservation status | |

|---|---|

| EX | Extinct (0 species) |

| EW | Extinct in the wild (0 species) |

| CR | Critically Endangered (1 species) |

| EN | Endangered (0 species) |

| VU | Vulnerable (2 species) |

| NT | Near threatened (0 species) |

| LC | Least concern (7 species) |

Conservation status codes listed follow the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Range maps are provided wherever possible; if a range map is not available, a description of the pilosan's range is provided. Ranges are based on the IUCN Red List for that species unless otherwise noted. All extinct species or subspecies listed alongside extant species went extinct after 1500 CE, and are indicated by a dagger symbol "†".

Classification

The order Pilosa consists of twelve extant species in two suborders: Folivora, the sloths, and Vermilingua, the anteaters. Folivora contains two families: Bradypodidae, containing four species in one genus; and Choloepodidae, containing two species in one genus. Vermilingua also contains two families: Cyclopedidae, containing a single species, and Myrmecophagidae, containing three species in two genera. Many of these species are further subdivided into subspecies. This does not include hybrid species or extinct prehistoric species.

Suborder Folivora

- Family Bradypodidae

- Genus Bradypus (three-toed sloths): four species

- Family Choloepodidae

- Genus Choloepus (two-toed sloths): two species

Suborder Vermilingua

- Family Cyclopedidae

- Genus Cyclopes (silky anteater): one species

- Family Myrmecophagidae

- Genus Myrmecophaga (giant anteater): one species

- Genus Tamandua (tamanduas): two species

Pilosans

The following classification is based on the taxonomy described by the reference work Mammal Species of the World (2005), with augmentation by generally accepted proposals made since using molecular phylogenetic analysis, as supported by both the IUCN and the American Society of Mammalogists.[4]

Suborder Folivora

Bradypodidae

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown-throated sloth

|

B. variegatus Schinz, 1825 Seven subspecies

|

Central America and northern South America |

Size: 42–80 cm (17–31 in) long, plus 2–9 cm (1–4 in) tail[5] Habitat: Forest[6] Diet: Leaves, flowers, and fruit of Cecropia trees[7] |

LC

|

| Maned sloth

|

B. torquatus Illiger, 1811 |

Eastern South America |

Size: 45–50 cm (18–20 in) long, plus 4–5 cm (2 in) tail[8] Habitat: Forest[9] Diet: Leaves[8] |

VU

|

| Pale-throated sloth

|

B. tridactylus Linnaeus, 1758 |

Northern South America |

Size: 45–75 cm (18–30 in) long, plus 4–6 cm (2 in) tail[10] Habitat: Forest[11] Diet: Twigs, buds, and leaves of Cecropia trees[12] |

LC

|

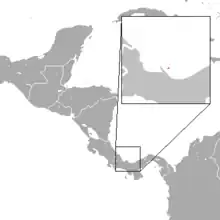

| Pygmy three-toed sloth

|

B. pygmaeus Anderson, Handley, 2001 |

Isla Escudo de Veraguas in Panama |

Size: 48–53 cm (19–21 in) long, plus 4–6 cm (2 in) tail[13] Habitat: Forest[14] Diet: Leaves[15] |

CR

|

Choloepodidae

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoffmann's two-toed sloth

|

C. hoffmanni Peters, 1858 Five subspecies

|

Central America and northern and western South America |

Size: 54–72 cm (21–28 in) long, plus 1–3 cm (1 in) tail[16] Habitat: Forest, shrubland, and grassland[17] Diet: Leaves, as well as buds, twigs, shoots, fruits, and flowers[18] |

LC

|

| Linnaeus's two-toed sloth

|

C. didactylus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Northern South America |

Size: 60–86 cm (24–34 in) long, plus 1–2 cm (1 in) tail[19] Habitat: Forest[20] Diet: Berries, leaves, small twigs, and fruit, as well as insects[21] |

LC

|

Suborder Vermilingua

Cyclopedidae

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silky anteater

|

C. didactylus (Linnaeus, 1758) Seven subspecies

|

Central America and northern and eastern South America |

Size: 36–45 cm (14–18 in) long, plus 18–27 cm (7–11 in) tail[22] Habitat: Forest[23] Diet: Ants and termites[24] |

LC

|

Myrmecophagidae

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giant anteater

|

M. tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758 Three subspecies

|

Central America and South America (former range in red) |

Size: 100–120 cm (39–47 in) long, plus 65–90 cm (26–35 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest, savanna, shrubland, and grassland[26] Diet: Ants, termites, and soft-bodied grubs[25] |

VU

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern tamandua

|

T. mexicana (Saussure, 1860) Four subspecies

|

Central America and northern South America |

Size: 47–77 cm (19–30 in) long, plus 40–68 cm (16–27 in) tail[27] Habitat: Forest and savanna[28] Diet: Ants and termites[27] |

LC

|

| Southern tamandua

|

T. tetradactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) Four subspecies

|

South America |

Size: 53–88 cm (21–35 in) long, plus 40–59 cm (16–23 in) tail[29] Habitat: Forest, savanna, and shrubland[30] Diet: Ants and termites, as well as bees and honey[30] |

LC

|

References

- ↑ "Fossilworks: Pilosa". Paleobiology Database. University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ↑ Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology and Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ↑ Gibb, G. C.; Condamine, F. L.; Kuch, M.; Enk, J.; Moraes-Barros, N.; Superina, M.; Poinar, H. N.; Delsuc, F. (2015). "Shotgun Mitogenomics Provides a Reference PhyloGenetic Framework and Timescale for Living Xenarthrans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (3): 621–642. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv250. PMC 4760074. PMID 26556496.

- ↑ Wilson, Reeder, pp. 100–103

- ↑ Hayssen, V. (2010). "Bradypus variegatus (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)". Mammalian Species. 42 (850): 19–32. doi:10.1644/850.1.

- 1 2 Moraes-Barros, N.; Chiarello, A.; Plese, T.; Santos, P.; Aliaga-Rossel, E.; Aguilar Borbón, A.; Turcios Casco, M. (2022). "Bradypus variegatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T3038A210442893.

- ↑ Jung, Hee-Jin (2011). "Bradypus variegatus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Bullinger, Brady (2009). "Bradypus torquatus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Chiarello, A.; Santos, P.; Moraes-Barros, N.; Miranda, F. (2022). "Bradypus torquatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T3036A210442361.

- ↑ Hayssen, V. (2009). "Bradypus tridactylus (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)" (PDF). Mammalian Species (839): 1–9. doi:10.1644/839.1. S2CID 85870343.

- 1 2 Pool, M.; De Thoisy, B.; Moraes-Barros, N.; Chiarello, A. (2022). "Bradypus tridactylus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T3037A210442660.

- ↑ Hughes, Kelly (2023). "Bradypus tridactylus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ↑ Anderson, R. P.; Handley Jr., C. O. (2001). "A new species of three-toed sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra) from Panama, with a review of the genus Bradypus". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 114 (1): 1–33.

- 1 2 Smith, D.; Voirin, B.; Chiarello, A.; Moraes-Barros, N. (2022). "Bradypus pygmaeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T61925A210445926.

- ↑ Guarino, Farryn (2009). "Bradypus pygmaeus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ↑ Gilmore, D. P.; Da Costa, C. P.; Duarte, D. P. F. (January 2001). "Sloth biology: an update on their physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 34 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1590/s0100-879x2001000100002. PMID 11151024.

- 1 2 Plese, T.; Chiarello, A.; Turcios Casco, M.; Aguilar Borbón, A.; Santos, P.; Aliaga-Rossel, E.; Moraes-Barros, N. (2022). "Choloepus hoffmanni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T4778A210443596.

- ↑ Apostolopoulos, Vicky (2010). "Choloepus hoffmanni". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Redford, Reid, Bonner (vol. 3), p. 97

- 1 2 Chiarello, A.; Plese, T.; De Thoisy, B.; Pool, M.; Aliaga-Rossel, E.; Santos, P.; Moraes-Barros, N. (2022). "Choloepus didactylus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T4777A210443323.

- ↑ Felton-Church, Ali (2000). "Choloepus didactylus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Redford, Reid, Bonner (vol. 3), p. 91

- 1 2 Miranda, F.; Meritt, D. A.; Tirira, D. G.; Arteaga, M. (2014). "Cyclopes didactylus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T6019A47440020. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T6019A47440020.en.

- ↑ Schober, Megan (2023). "Cyclopes didactylus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- 1 2 Woltanski, Amy (2004). "Myrmecophaga tridactyla". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Miranda, F.; Bertassoni, A.; Abba, A. M. (2014). "Myrmecophaga tridactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T14224A47441961. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T14224A47441961.en.

- 1 2 Harrold, Andria (2007). "Tamandua mexicana". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Ortega Reyes, J.; Tirira, D. G.; Arteaga, M.; Miranda, F. (2014). "Tamandua mexicana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21349A47442649. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21349A47442649.en.

- ↑ Gorog, Antonia (2023). "Tamandua tetradactyla". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Miranda, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Arteaga, M.; Tirira, D. G.; Meritt, D. A.; Superina, M. (2014). "Tamandua tetradactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21350A47442916. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21350A47442916.en.

Sources

- Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H.; Reid, Fiona; Bonner, Sigrid James (1989). Mammals of the Neotropics. Vol. 3: Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-19542-1.

- Gardner, Alfred L. (2005). Wilson, Don E.; Reeder, DeeAnn M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

.JPG.webp)

_crop.jpg.webp)