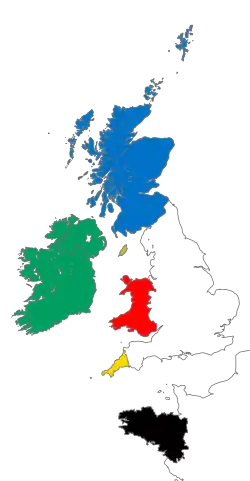

In addition to English, literature has been written in a wide variety of other languages in Britain, that is the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands (the Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey are not part of the United Kingdom, but are closely associated with it, being British Crown Dependencies). This includes literature in Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, Latin, Cornish, Anglo-Norman, Guernésiais, Jèrriais, Manx, and Irish (but the last of these only in Northern Ireland after 1922). Literature in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) is treated as English literature and literature in Scots as Scottish literature.

British identity

The nature of British identity has changed over time. The island that contains England, Scotland, and Wales has been known as Britain from the time of the Roman Pliny the Elder (c. AD 23–79).[1] Though the original inhabitants spoke mainly various Celtic languages, English as the national language had its beginnings with the Anglo-Saxon invasion of c.450 A.D.[2]

The various constituent parts of the present United Kingdom joined at different times. Wales was annexed by the Kingdom of England under the Acts of Union of 1536 and 1542, and it was not until 1707 with a treaty between England and Scotland, that the Kingdom of England became the Kingdom of Great Britain. This merged in 1801 with the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Until fairly recent times Celtic languages were spoken in Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland, and still survive, especially in parts of Wales

Subsequently, the impact of British Unionism led to the partition of the island of Ireland in 1921, which means that literature of the Republic of Ireland is not British, although literature from Northern Ireland, is both Irish and British.[3] More recently the relationship between England and Wales and Scotland, has changed, through the establishment of parliaments in both those countries, in addition to the British parliament in London.

Early Britain: 450 – 1100 A.D.

Latin literature, mostly ecclesiastical, continued to be written in the centuries following the withdrawal of the Roman Empire at the beginning of the fifth-century, including Chronicles by Bede (672/3–735), Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, and Gildas (c. 500–570), De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae.

Various Celtic languages were spoken by many of British people at this time and among the most important written works that have survived are Y Gododdin i and the Mabinogion. Y Gododdin is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Britonnic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia at a place named Catraeth in c. AD 600. It is traditionally ascribed to the bard Aneirin, and survives only in one manuscript, known as the Book of Aneirin.[4] The name Mabinogion is a convenient label for a collection eleven prose stories collated from two medieval Welsh manuscripts known as the White Book of Rhydderch (Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch) (c. 1350) and the Red Book of Hergest (Llyfr Coch Hergest) (1382–1410). They are written in Middle Welsh, the common literary language between the end of the eleventh century and the fourteenth century. They include the four tales that form Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi ("The Four Branches of the Mabinogi"). The tales draw on pre-Christian Celtic mythology, international folktale motifs, and early medieval historical traditions.

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, Vikings and Norse settlers and their descendants colonised parts of what is now modern Scotland. Some Old Norse poetry survives relating to this period, including the Orkneyinga saga an historical narrative of the history of the Orkney Islands, from their capture by the Norwegian king in the ninth century onwards until about 1200.[5]

Late medieval period: 1100–1500

Following the Norman conquest in 1066, the Norman language became the language of England's nobility. During the whole of the 12th century the Anglo-Norman language (the variety of Norman used in England) shared with Latin the distinction of being the literary language of England, and it was in use at the court until the 14th century. It was not until the reign of Henry VII that English became the native tongue of the kings of England.

Works were still written in Latin and include Gerald of Wales's late-12th-century book on his beloved Wales, Itinerarium Cambriae, and following the Norman Conquest of 1066, Anglo-Norman literature developed in the Anglo-Norman realm introducing literary trends from Continental Europe, such as the chanson de geste. However, the indigenous development of Anglo-Norman literature was precocious in comparison to continental Oïl literature.[6]

Geoffrey of Monmouth was one of the major figures in the development of British history and the popularity for the tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) of 1136, which spread Celtic motifs to a wider audience. Wace (c. 1110 – after 1174), who wrote in Norman-French, is the earliest known poet from Jersey, also developed the Arthurian legend.[7]) At the end of the 12th century, Layamon in Brut adapted Wace to make the first English language work to use the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

Early English Jewish literature developed after the Norman Conquest with Jewish settlement in England. Berechiah ha-Nakdan is known chiefly as the author of a 13th-century set of over a hundred fables, called Mishle Shualim, (Fox Fables).[8] The development of Jewish literature in medieval England ended with the Edict of Expulsion of 1290.

The multilingual nature of the audience for literature in the 14th century can be illustrated by the example of John Gower (c. 1330 – October 1408). A contemporary of William Langland and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer, Gower is remembered primarily for three major works, the Mirroir de l'Omme, Vox Clamantis, and Confessio Amantis, three long poems written in Anglo-Norman, Latin, and Middle English respectively, which are united by common moral and political themes.[9]

Dafydd ap Gwilym (c. 1315/1320 – c. 1350/1370), is widely regarded as the leading Welsh poet[10][11][12][13] and amongst the great poets of Europe in the Middle Ages. His main themes are love and nature. The influence of the ideas of courtly love, found in the troubadour poetry of Provençal, was a significant influence on his poetry.[14]

Major Scottish writers from the 15th century include Henrysoun, Dunbar, Douglas and Lyndsay, who wrote in Middle Scots, often simply called English, the dominant language of Scotland.

In the Cornish language, Passhyon agan Arloedh ("The Passion of our Lord"), a poem of 259 eight-line verses written in 1375, is one of the earliest surviving works of Cornish literature. The most important work of literature surviving from the Middle Cornish period is An Ordinale Kernewek ("The Cornish Ordinalia"), a 9000-line religious drama composed around the year 1400. Three plays in Cornish known as the Ordinalia have survived from this period.[15]

The Renaissance: 1500–1660

The spread of printing affected the transmission of literature across Britain and Ireland. The first book printed in English, William Caxton's own translation of Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, was printed abroad in 1473, to be followed by the establishment of the first printing press in England in 1474. The establishment of a printing press in Scotland under royal patent from James IV in 1507 made it easier to disseminate Scottish literature.[16] The first printing press in Ireland followed later in 1551. Although the first book in Welsh to be printed was produced by John Prise in 1546, restrictions on printing meant that only clandestine presses, such as that of Robert Gwyn who published Y Drych Cristionogawl in 1586/1587, could operate in Wales until 1695. The first legal printing press to be set up in Wales was in 1718 by Isaac Carter.[17] The first printed work in Manx dates from 1707: a translation of a Prayer Book catechism in English by Bishop Thomas Wilson. Printing arrived even later in other parts of Britain and Ireland: the first printing press in Jersey was set up by Mathieu Alexandre in 1784.[18] The earliest datable text in Manx (preserved in 18th-century manuscripts), a poetic history of the Isle of Man from the introduction of Christianity, dates to the 16th century at the latest.

The reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England (1558–1603) and of King James I (1603–162) (James VI of Scotland), saw the development of Britishness in literature. In anticipation of James VI's expected inheritance of the English throne, court masques in England were already developing the new literary imagery of a united "Great Britain", sometimes delving into Roman and Celtic sources.[19] William Camden's Britannia, a county by county description of Great Britain and Ireland, was an influential work of chorography: a study relating landscape, geography, antiquarianism, and history. Britannia came to be viewed as the personification of Britain, in imagery that developed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

The Renaissance in Wales was marked by humanism and scholarship. The Welsh language, its grammar and lexicography, was studied for the first time and biblical studies flourished. Welsh writers such as John Owen and William Vaughan wrote in Latin or English to communicate their ideas outside Wales, but the humanists were unsuccessful in opening the established practices of professional Welsh poets to Renaissance influences.[17] From the Reformation until the 19th century most literature in the Welsh language was religious in character. Morgan Llwyd's Llyfr y Tri Aderyn ("The Book of the Three Birds") (1653) took the form of a dialogue between an eagle (representing secular authority, particularly Cromwell); a dove (representing the Puritans); and a raven (representing the Anglican establishment).

The Reformation and vernacular literature

At the Reformation, the translation of liturgy and Bible into vernacular languages provided new literary models. The Book of Common Prayer and the Authorized King James Version of the Bible have been hugely influential. The King James Bible, one of the biggest translation projects in the history of English up to this time, was started in 1604 and completed in 1611.

The earliest surviving examples of Cornish prose are Pregothow Treger (The Tregear Homilies), a set of 66 sermons translated from English by John Tregear 1555–1557.

In 1567 William Salesbury's Welsh translations of the New Testament and Book of Common prayer were published. William Morgan's translation of the whole Bible followed in 1588 and remained the standard Welsh Bible until well into the 20th century.

The first Irish translation of the New Testament was begun by Nicholas Walsh, Bishop of Ossory, continued by John Kearney (Treasurer of St Patrick's, Dublin), his assistant, and Dr. Nehemiah Donellan, Archbishop of Tuam, and finally completed by William O'Domhnuill (William Daniell, Archbishop of Tuam in succession to Donellan). Their work was printed in 1602.[20] The work of translating the Old Testament was undertaken by William Bedell (1571–1642), Bishop of Kilmore, who completed his translation within the reign of Charles the First. However, it was not published until 1685, in a revised version by Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713), Archbishop of Dublin.[21][22]

The Book of Common Order was translated into Scottish Gaelic by Séon Carsuel (John Carswell), Bishop of the Isles, and printed in 1567. This is considered the first printed book in Scottish Gaelic though the language resembles classical Irish.[23] The Irish translation of the Bible dating from the Elizabethan period was in use in Scotland until the Bible was translated into Scottish Gaelic.[24] James Kirkwood (1650–1709) promoted Gaelic education and attempted to provide a version of William Bedell's Bible translations into Irish, edited by his friend Robert Kirk (1644–1692), which failed, though he did succeed in publishing a Psalter in Gaelic (1684).[25][26]

The Book of Common Prayer was translated into French by Jerseyman Jean Durel, later Dean of Windsor, and published for use in the Channel Islands in 1663 as Anglicanism was established as the state religion after the Stuart Restoration.

The Book of Common Prayer and Bible were translated into Manx in the 17th and 18th centuries. The printing of prayers for the poor families was projected by Thomas Wilson in a memorandum of Whit-Sunday 1699, but was not carried out until 30 May 1707, the date of issue of his Principles and Duties of Christianity ... in English and Manks, with short and plain directions and prayers, 1707. This was the first book published in Manx, and is often styled the Manx Catechism. The Gospel of St. Matthew was translated, with the help of his vicars-general in 1722 and published in 1748 under the sponsorship of his successor as bishop, Mark Hildesley. The remaining Gospels and the Acts were also translated into Manx under his supervision, but not published. Hildesley printed the New Testament and the Book of Common Prayer, translated, under his direction, by the clergy of the diocese, and the Old Testament was finished and transcribed in December 1772, at the time of the bishop's death.[27] The Manx Bible established a standard for written Manx. A tradition of Manx carvals, religious songs or carols, developed. Religious literature was common, but secular writing much rarer.

Translations of parts of the Bible into Cornish have existed since the 17th century. The early works involved the translation of individual passages, chapters or books of the Bible

Latin literature

Latin continued in use as a language of learning, long after the Reformation had established the vernacular as the liturgical language. In Scotland, Latin as a literary language thrived into the 17th century as Scottish writers writing in Latin were able to engage with their audiences on an equal basis in a prestige language without feeling hampered by their less confident handling of English.[28]

Utopia is a work of fiction and political philosophy by Thomas More (1478–1535) published in 1516. The book, written in Latin, is a frame narrative primarily depicting a fictional island society and its religious, social and political customs. New Atlantis is a utopian novel by Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626), published in Latin (as Nova Atlantis) in 1624 and in English in 1627. In this work, Bacon portrayed a vision of the future of human discovery and knowledge, expressing his aspirations and ideals for humankind. The novel depicts the creation of a utopian land where "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendour, piety and public spirit" are the commonly held qualities of the inhabitants of the mythical Bensalem. The plan and organisation of his ideal college, Salomon's House (or Solomon's House), envisioned the modern research university in both applied and pure sciences.

Scotsman George Buchanan (1506–1582) was the Renaissance writer from Britain (and Ireland) who had the greatest international reputation, being considered the finest Latin poet since classical times.[29] As he wrote mostly in Latin, his works travelled across Europe as did he himself. His Latin paraphrases of the Hebrew Psalms (composed while Buchanan was imprisoned by the Inquisition in Portugal) remained in print for centuries and were used into the 19th century for the purposes of studying Latin Amongst English poets who wrote poems in Latin in the 17th century were George Herbert (1593–1633) (who also wrote poems in Greek), and John Milton (1608–74).

Philosopher Thomas Hobbes' Elementa Philosophica de Cive (1642–1658) was in Latin. However, things were changing and by about 1700 the growing movement for the use of national languages (already found earlier in literature and the Protestant religious movement) had reached academia, and an example of the transition is Isaac Newton's writing career, which began in Neo-Latin and ended in English: Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica in Latin Opticks, 1704, in English.

The Restoration: 1660–1700

Iain Lom (c. 1624 – c. 1710) was a Royalist Scottish Gaelic poet appointed poet laureate in Scotland by Charles II at the Restoration. He delivered a eulogy for the coronation, and remained loyal to the Stuarts after 1688, opposing the Williamites and later, in his vituperative Oran an Aghaidh an Aonaidh, the 1707 Union of the Parliaments.[29]

Cín Lae Uí Mhealláin is an account of the Irish Confederate Wars which "reflected the Ulster Catholic point of view" written by Tarlach Ó Mealláin.

Nicholas Boson (1624–1708) wrote three significant texts in Cornish, Nebbaz gerriau dro tho Carnoack (A Few Words about Cornish) between 1675 and 1708; Jowan Chy-an-Horth, py, An try foynt a skyans (John of Chyannor, or, The three points of wisdom), published by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, though written earlier; and The Dutchess of Cornwall's Progress, partly in English, now known only in fragments. The first two are the only known surviving Cornish prose texts from the 17th century.[30]

In Scotland, after the 17th century, anglicisation increased, though Lowland Scots was still spoken by the vast majority of the population, and Scottish Gaelic by a minority. At the time, many of the oral ballads from the borders and the North East were written down. The 17th century probably also saw the composition in Orkney of the only original literary work in the Norn language, a ballad called "Hildina".[31] Writers of the period include Robert Sempill (c. 1595 – 1665), Lady Wardlaw and Lady Grizel Baillie.

18th century

The Union of the Parliaments of Scotland and England in 1707 to form a single Kingdom of Great Britain and the creation of a joint state by the Acts of Union had little impact on the literature of England nor on national consciousness among English writers. The situation in Scotland was different: the desire to maintain a cultural identity while partaking of the advantages offered by the English literary market and English literary standard language led to what has been described as the "invention of British literature" by Scottish writers. English writers, if they considered Britain at all, tended to assume it was merely England writ large; Scottish writers were more clearly aware of the new state as a "cultural amalgam comprising more than just England".[32]

Ellis Wynne's Gweledigaetheu y Bardd Cwsc ('Visions of the Sleeping Bard'), first published in London in 1703, is regarded as a Welsh language classic. It is generally said that no better model exists of such 'pure' idiomatic Welsh, before writers had become influenced by English style and method.

A mover in the classical revival of Welsh literature in the 18th century was Lewis Morris, one of the founders in 1751 of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, a Welsh literary society in London—at that time the most important centre of Welsh publishing.[17] He set out to counter the trend among patrons of Welsh literature to turn towards English culture. He attempted to recreate a classic school of Welsh poetry with his support for Goronwy Owen and other Augustans. Goronwy Owen's plans for a Miltonic epic were never achieved, but influenced the aims of eisteddfodau competitions through the 19th century.[33]

The Scottish Gaelic Enlightenment figure Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair compiled the first secular book in Scottish Gaelic to be printed: Leabhar a Theagasc Ainminnin (1741), a Gaelic-English glossary. The second secular book in Scottish Gaelic to be published was his poetry collection Ais-Eiridh na Sean Chánoin Albannaich (The Resurrection of the Ancient Scottish Language). Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair was the most overtly nationalist poet in Gaelic of the 18th century.[28] He was influenced by James Thomson's The Seasons as well as by Gaelic "village poets" such as Iain Mac Fhearchair (John MacCodrum). As part of the oral literature of the Highlands, few of the works of such village poets were published at the time, although some have been collected since.[28]

Scottish Gaelic poets produced laments on the Jacobite defeats of 1715 and 1745. Mairghread nighean Lachlainn and Catriona Nic Fhearghais are among woman poets who reflected on the crushing effects on traditional Gaelic culture of the aftermath of the Jacobite uprisings. A consequent sense of desolation pervaded the works of Scottish Gaelic writers such as Dughall Bochanan which mirrored many of the themes of the graveyard poets writing in England.[28] A legacy of Jacobite verse was later compiled (and adapted) by James Hogg in his Jacobite Reliques (1819).

In the Scots-speaking areas of Ulster there was traditionally a considerable demand for the work of Scottish poets, often in locally printed editions. These included Alexander Montgomerie's The Cherrie and the Slae in 1700, over a decade later an edition of poems by Sir David Lindsay, and nine printings of Allan Ramsay's The Gentle shepherd between 1743 and 1793.

19th century

The Welsh novel in English starts with "The Adventures and Vagaries of Twm Shon Catti" (1828) by T. J. Ll. Prichard, and novelists following him developed two important genres: the industrial novel and the rural romance. Serial fiction in Welsh had been appearing from 1822 onwards, but the work to be recognisable as the first novel in Welsh was William Ellis Jones' 1830 "Y Bardd, neu y Meudwy Cymreig". This was a moralistic work, as were many of the productions of the time. The first major novelist in the Welsh language was Daniel Owen (1836–1895), author of works such as Rhys Lewis (1885) and Enoc Huws (1891).[17]

The first novel in Scottish Gaelic was John MacCormick's Dùn-Àluinn, no an t-Oighre 'na Dhìobarach, which was serialised in the People's Journal in 1910, before publication in book form in 1912. The publication of a second Scottish Gaelic novel, An t-Ogha Mòr by Angus Robertson, followed within a year.[34]

Philippe Le Sueur Mourant's Jèrriais tales of Bram Bilo, an innocent abroad in Paris, were an immediate success in Jersey in 1889 and went through a number of reprintings.[35]

Ewen MacLachlan (Gaelic: Eoghan MacLachlainn) (1775–1822) was a Scots poet of this period who translated the first eight books of Homer's Iliad into Scottish Gaelic. He also composed and published his own Gaelic Attempts in Verse (1807) and Metrical Effusions (1816), and contributed greatly to the 1828 Gaelic–English Dictionary.

Denys Corbet published collections of Guernésiais poems Les Feuilles de la Forêt (1871) and Les Chànts du draïn rimeux (1884), and also brought out an annual poetry anthology 1874–1877, similar to Augustus Asplet Le Gros's annual in Jersey 1868–1875.[35]

Increased literacy in rural and outlying areas and wider access to publishing through, for example, local newspapers encouraged regional literary development as the 19th century progressed. Some writers in lesser-used languages and dialects of the islands gained a literary following outside their native regions, for example William Barnes (1801–86) in Dorset, George Métivier (1790–1881) in Guernsey and Robert Pipon Marett (1820–84) in Jersey.[35]

George Métivier published Rimes Guernesiaises, a collection of poems in Guernésiais and French in 1831 and Fantaisies Guernesiaises in 1866. Métivier's poems had first appeared in newspapers from 1813 onward, but he spent time in Scotland in his youth where he became familiar with the Scots literary tradition although he was also influenced by Occitan literature. The first printed anthology of Jèrriais poetry, Rimes Jersiaises, was published in 1865.

The so-called "Cranken Rhyme" produced by John Davey of Boswednack, one of the last people with some traditional knowledge of the language,[36] may be the last piece of traditional Cornish literature.

John Ceiriog Hughes desired to restore simplicity of diction and emotional sincerity and do for Welsh poetry what Wordsworth and Coleridge did for English poetry.

Edward Faragher (1831–1908) has been considered the last important native writer of Manx. He wrote poetry, reminiscences of his life as a fisherman, and translations of selected Aesop's Fables.

The development of Irish literary culture was encouraged in the late 19th and early 20th century by the Irish Literary Revival (see also The Celtic Revival), which was supported by William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), Augusta, Lady Gregory, and John Millington Synge. The Revival stimulated a new appreciation of traditional Irish literature. This was a nationalist movement that also encouraged the creation of works written in the spirit of Irish, as distinct from British culture. While drama was an important component of this movement, it also included prose and poetry.

20th century

Dòmhnall Ruadh Chorùna was a Scottish Gaelic poet who served in the First World War, and as a war poet described the use of poison gas in his poem Òran a' Phuinnsuin ("Song of the Poison"). He also wrote the love song An Eala Bhàn ("The White Swan"). Welsh poet Hedd Wyn, who was killed in World War I, was later the subject of an Oscar-nominated Welsh film.[17] In Parenthesis, an epic poem by David Jones first published in 1937, is a notable work of the literature of the First World War, that was influenced by Welsh traditions, despite Jones being born in England. Poetry reflecting life on the home-front was also published; Guernésiais writer Thomas Henry Mahy's collection Dires et Pensées du Courtil Poussin, published in 1922, contained some of his observational poems published in La Gazette de Guernesey during the war.

In the late 19th century and early twentieth-century, Welsh literature began to reflect the way the Welsh language was increasingly becoming a political symbol. Two important literary nationalists were Saunders Lewis (1893–1985) and Kate Roberts (1891–1985), both of whom began publishing in the 1920s. Kate Roberts' and Saunders Lewis's careers continued after World War II and they both were among the foremost Welsh-language authors of the twentieth century.

The year 1922 marked a significant change in the relationship between Great Britain and Ireland, with the setting up of the Irish Free State in the predominantly Catholic South, while the predominantly Protestant Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom. Nationalist movements in Britain, especially in Wales and Scotland, also significantly influenced writers in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Referendums held in Wales and in Scotland eventually resulted in the establishment of a form of self-government in both countries.

The Scottish Gaelic Renaissance (Scottish Gaelic: Ath-Bheòthachadh na Gàidhlig) is a continuing movement concerning the revival of the Scottish Gaelic language. Although the Scottish Gaelic language had been facing gradual decline in the number of speakers since the late 19th century, the number of young fluent Gaelic speakers is rising due to Gaelic-medium education.[37] The movement has its origins in the Scottish Renaissance, especially in the work of Sorley MacLean, George Campbell Hay, Derick Thomson and Iain Crichton Smith. Sabhal Mòr Ostaig is sometimes seen as being a product of this renaissance. Although many of the products of the Renaissance are in poetry, or in traditional music, many such as MacLean and Iain Crichton Smith, and more recently Aonghas MacNeacail have blended these with modern international styles.

21st century literature

Contemporary writers in Scottish Gaelic include Aonghas MacNeacail, and Angus Peter Campbell who, besides two Scottish Gaelic poetry collections, has produced two Gaelic novels: An Oidhche Mus Do Sheol Sinn (2003) and Là a' Deanamh Sgeil Do Là (2004). A collection of short stories P'tites Lures Guernésiaises (in Guernésiais with parallel English translation) by various writers was published in 2006.[38] In March 2006 Brian Stowell's Dunveryssyn yn Tooder-Folley (The vampire murders) was published—the first full-length novel in Manx.[39] There is some production of modern literature in Irish in Northern Ireland. Performance poet Gearóid Mac Lochlainn exploits the creative possibilities for poetry of "creolised Irish" in Belfast speech.[40]

The theatrical landscape has been reconfigured, moving from a single national theatre at the end of the twentieth-century to four as a result of the devolution of cultural policy.[41]

With the revival of Cornish there have been newer works written in the language. The first full translation of the Bible into Cornish was published in 2011.[42]

See also

References

- ↑ Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia Book IV. Chapter XLI Latin text and English translation, numbered Book 4, Chapter 30, at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Jones & Casey 1988:367–98 "The Gallic Chronicle Restored: a Chronology for the Anglo-Saxon Invasions and the End of Roman Britain"

- ↑ Deane, Seamus (1986). A Short History of Irish Literature. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091613612.

- ↑ Jackson (1969)—the work is titled The Gododdin: the oldest Scottish poem.

- ↑ "Orkneyjar - The History and Archaeology of the Orkney Islands".

- ↑ Language and Literature, Ian Short, in A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World, edited Christopher Harper-Bill and Elisabeth van Houts, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-673-8

- ↑ Burgess, ed., xiii;

- ↑ "Adventures in Philosophy: A Brief History of Jewish Philosophy". Radicalacademy.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Volume 5. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 1770. ISBN 1851094407. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Bromwich, Rachel (1979). "Dafydd ap Gwilym". In Jarman, A. O. H.; Hughes, Gwilym Rees (eds.). A Guide to Welsh Literature. Volume 2. Swansea: Christopher Davies. p. 112. ISBN 0715404571. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ Baswell, Christopher; Schotter, Anne Howland, eds. (2006). The Longman Anthology of British Literature. Volume 1A: The Middle Ages (3rd ed.). New York: Pearson Longman. p. 608. ISBN 0321333977.

- ↑ Kinney, Phyllis (2011). Welsh Traditional Music. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780708323571. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ Rachel Bromwich, Aspects of the Poetry of Dafydd ap Gwilym (Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 1986).

- ↑ A Handbook of the Cornish Language, by Henry Jenner A Project Gutenberg eBook;A brief history of the Cornish language Archived 2008-12-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 26–9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stephens, Meic (1998). The New Companion to the Literature of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708313833.

- ↑ Balleine's History of Jersey. Société Jersiaise. 1998. ISBN 1860770657.

- ↑ British Identities and English Renaissance Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 9780521189682.

- ↑ William O'Domhnuill's (Daniel's) Translation of the New Testament into Irish. Retrieved on 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Treasures of the Irish Language: Some early examples from Dublin City Public Libraries". 2006. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Bedell's Irish Old Testament". King's College London. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Felicity Heal Reformation in Britain and Ireland – Page 282 2005 "In Irish the catechism long preceded the printing of the New Testament, while in Scottish Gaelic the Form of Common Order was printed in 1567, the full Bible not until 1801. Manx Gaelic had no Bible until the eighteenth century:"

- ↑ Mackenzie, Donald W. (1990–92). "The Worthy Translator: How the Scottish Gaels got the Scriptures in their own Tongue". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 57: 168–202.

- ↑ Tony Claydon, Ian McBride – Protestantism and National Identity: Britain and Ireland Page 176 2007 "The failure of Kirkwood's scheme, and in particular of the Scottish Gaelic bible, which had been adapted from the original Irish translation by Kirkwood's friend Robert Kirk, has often been attributed to the incompatibility of Irish and ."

- ↑ William Ferguson – The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest Page 243 1998 "Here it is salutary to recall the difficulties that Robert Kirk had experienced when turning the Irish Bible into Scottish Gaelic. Those difficulties were real and by no means imaginary or due to fastidious pedantry on Kirk's part."

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- 1 2 3 4 Crawford, Robert (2007). Scotland's Books. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140299403.

- 1 2 Watson, Roderick (2007). The Literature of Scotland. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333666647.

- ↑ The Cornish writings of the Boson family: Nicholas, Thomas and John Boson, of Newlyn, circa 1660 to 1730, Edited with translations and notes by O. J. Padel (Redruth: Institute of Cornish Studies, 1975) ISBN 0-903686-09-0

- ↑ Barnes, Michael (1984). "Orkney and Shetland Norn". In Trudgill, Peter (ed.). Language in the British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 358. ISBN 0521284090.

- ↑ Crawford, Robert (1992). Devolving English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198119550.

- ↑ Williams, Gwyn A. (1985). When was Wales?. London: Penguin. ISBN 0140225897.

- ↑ "The forgotten first: John Maccormick's DÙN-ÀLUINN" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 La Grève de Lecq, Roger Jean Lebarbenchon, 1988 ISBN 2-905385-13-8

- ↑ Ellis, P. B. The Cornish language and its literature; p. 129.

- ↑ , Scotsman,2007.

- ↑ P'tites Lures Guernésiaises, edited Hazel Tomlinson, Jersey 2006, ISBN 1-903341-47-7

- ↑ "Isle of Man Today article on Dunveryssyn yn Tooder-Folley". Iomonline.co.im. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Mac Póilin, Aodán. "Irish language literature in Belfast". The Cities of Belfast. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Dickson, Andrew (2 August 2011). "Edinburgh festival 2011: where National Theatres meet". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ An Beybel Sans: The Holy Bible in Cornish