| River Little Ouse | |

|---|---|

The river north of Lakenheath | |

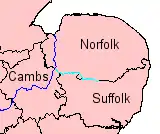

Little Ouse (light blue) and Great Ouse (dark) | |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| Counties | Norfolk, Suffolk |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Thelnetham, Norfolk/Suffolk border |

| • coordinates | 52°22′16″N 0°59′39″E / 52.37124°N 0.99405°E |

| • elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Mouth | River Great Ouse |

• location | Brandon Creek, Littleport, Cambridgeshire |

• coordinates | 52°30′04″N 0°22′01″E / 52.50121°N 0.36704°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 37 mi (60 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Black Bourn, Lakenheath Lode |

| • right | River Thet |

The River Little Ouse, also known as the Brandon River, is a river in the east of England, a tributary of the River Great Ouse. For much of its length it defines the boundary between Norfolk and Suffolk.

It rises east of Thelnetham, close to the source of the River Waveney, which flows eastwards while the Little Ouse flows west. The village of Blo' Norton owes its name to the river: it was earlier known as Norton Bell-'eau, from being situated near this "fair stream". In this area the river creates a number of important wetland areas such as at Blo' Norton and Thelnetham Fens, and areas managed by the Little Ouse Headwaters Project.[1] The course continues through Rushford, Thetford, Brandon, and Hockwold before the river joins the Great Ouse north of Littleport in Cambridgeshire. The total length is about 37 miles (60 km).

The river is navigable from the Great Ouse to a point 2 miles (3.2 km) above Brandon.

Origins

A distinctive feature of the headwaters of the Little Ouse and the Waveney is the valley in which they flow; the Little Ouse flows westwards while the Waveney flows eastwards. The valley is broad, cutting through boulder clay to the north and to the south, but is crossed by a flat sandy feature at Lopham Ford, between South Lopham, Norfolk and Redgrave, Suffolk. Here the two rivers rise, barely 160 yards (150 m) apart, at an altitude of around 85 feet (26 m). The B1113 road crosses the valley on the sandy bank, known as The Frith, and which is the only crossing of the Norfolk border which is on dry land. To the east are the wetlands of Redgrave and Lopham Fens, while to the west is Hinderclay Fen. The whole area overlays a thick bed of chalk.[2]

The geological features of a large through valley, but no large river, are unusual, and were first recorded by Rev. Osmond Fisher in 1868, a keen geologist who thought the features were related to glaciation, but failed to convince the geologists of the 1870s. More recently, Prof Richard West carried out a detailed field study of the area between 2002 and 2007, and his work was published by the Suffolk Naturalists' Society in 2009. He concluded that the valley was caused by the runoff from a large glacial lake, which eventually melted, leaving the valley as it is today, with the sands of the lake bed becoming the sands of the Breckland, a large area of gorse-covered sandy heath that spans the border between Norfolk and Suffolk.[3][4]

The downstream end of the Little Ouse has changed much over the centuries. In the Fens and Norfolk Marshland, it was quite possible for the course of a river to change as the result of a flooding episode so it is not surprising to find that the Great Ouse used to enter The Wash by way of the Old Croft River, the Wellstream and Wisbech (the Ouse beach). The modern lower Great Ouse was then the lower part of the Little Ouse. On this occasion, the change was artificial. The 17th century drainers under Cornelius Vermuyden dug the Old Bedford River between the Great Ouse at Earith and what had hitherto been the Little Ouse at Denver. A link was made for the Great Ouse between Littleport and the Little Ouse at Brandon Creek, and both the drainage and the navigation were directed towards King's Lynn rather than Wisbech.

Route

Rising near the B1113 from South Lopham to Redgrave, the fledgeling Little Ouse flows west, and is joined by a stream flowing northwards from the hamlets of Rickinghall and Botesdale, before passing through Hinderclay Fen.[5] This was once a flourishing valley fen, and was a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), but the fen dried out as a result of changes to the river, made to improve drainage from surrounding agricultural land. Rare species died out, and the designation was removed in 1983, but recent action by the Little Ouse Headwaters Project has resulted in areas of wet fen being extended and species being reintroduced. They have been assisted in this by funding from the European Union.[6] The river crosses Thelnetham Road, Blo' Norton as a ford, near which is Thelnetham windmill, a grade II* listed tower mill dating from 1819 and restored in the 1980s.[7]

The course turns briefly to the north-west, and is crossed by the B1111 road to the south of Garboldisham. To the north of the bridge is Garboldisham windmill, a post mill dating from 1780. This is also a grade II* listed structure, although its sails and tiller beam are missing.[8] Continuing westwards, the river passes to the south of Gasthorpe, with the ruined church of All Saints a little further to the south. It was abandoned before 1900, and now has no roof.[9] Passing along the northern edge of Knettishall Heath Country Park, there are two weirs, after which the Peddars Way and Norfolk Coast Path cross on a footbridge. A minor road crosses at Rushford, where the bridge is a scheduled ancient monument,[10] and another bridge carries the A1088 into Thetford, beyond which is a weir. The Black Bourn river joins from the south, and the combined flow turns to the north to reach Thetford. The border between Norfolk and Suffolk has followed the river for most of its course, but skirts to the west of Thetford.[5]

As it approaches Thetford, the river passes through Nunnery Lakes Reserve, a nature reserve managed by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). A series of deep pools were created in the 1970s when gravel and sand were extracted, and the site is now a haven for wildlife. The BTO have their main offices at the northern end of the site,[11][12] near to Nuns Bridge Road, where there are three listed bridges, built on the line of Icknield Way, an ancient track thought to have been first used around 3000 BCE. The southernmost bridge, crossing the Little Ouse, dates from the late 18th century, and has two elliptical arches with a central cutwater.[13] The central bridge has a single semi-circular arch, and was built of brick in the early 19th century.[14] The northernmost crosses the River Thet, dates from the late 18th century, and has two elliptical arches, with splayed parapets and stone coping slabs.[15] For many years there was an open-air swimming pool on the widened river just above Nuns Bridges, but this closed in the late 1950s amid growing concerns over pollution, and an indoor swimming pool was eventually built to replace it.[16]

Below Thetford

Below the pool site, the river is joined by the River Thet, where there is a network of channels, sluices and weirs, together with the remains of a water mill, dating from the early 19th century. The building is now used as a masonic lodge. As it threads its way through the town, the river is crossed by Town Bridge, a single elliptical cast iron span dating from 1829,[17] and after it passes under the A11 Thetford Bypass, it is bordered by Thetford Forest. This is the largest manmade lowland forest in Britain, covering 72.3 square miles (187 km2).[18] There is a weir beyond the bridge, and the county border rejoins the river as it turns back towards the west. This section is easier to follow, as the St Edmund Way footpath runs along the north bank from the centre of Thetford, but leaves the river where the county boundary joins. The St Edmund Way continues to the north of the river, and the Little Ouse Path runs to the south. At Santon Downham, the Little Ouse Path continues along the north bank of the river, on the original towpath.[5]

The footpath leaves the river just before the A1065 bridge at Brandon, but rejoins it soon afterwards. Brandon Lock follows, with the lock chamber to the north and a large weir to the south. The Ely to Norwich Railway line crosses from the north bank to the south, and there is a Romano-British settlement site on the north bank. It lies at one end of the Foss Ditch, a waterway dating from the Saxon period that ran for 6 miles (9.7 km) between the Little Ouse and the River Wissey, which may have been used for defence.[19] The towpath stops following the river to the south of Hockwold cum Wilton, turning to the north.[5] The river has been diverted from its original course, to cross the Cut-off Channel in a concrete aqueduct. Large guillotine sluices control whether the water is fed into the lower river or along the Cut-off Channel.[19] As it rejoins its original course, it passes under Wilton Bridge, and there are footpaths on both sides, set back from the channel on flood banks.[5]

To the south of the river are a series of washes, meres and wooded stretches.[20] Parts of this area were formerly arable farmland, but were converted into the Lakenheath Fen wetland by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). The reedbeds and grazing marshes have attracted significant populations of reed warblers, sedge warblers, bearded tits, marsh harriers, and increasingly, bitterns.[21] At the western end of the fens is Botany Bay, where water from Lakenheath Old Lode and the Twelve Foot Drain is pumped into the river. A little further on is the confluence with another drain, called Lakenheath New Lode.[5]

The final 6 miles (10 km) of the river follow a relatively straight course which heads north-west to join the River Great Ouse at Brandon Creek. The channel is man-made, and probably dates from the Roman period. Prior to its construction, the river continued due west, and joined the Great Ouse near Old Bank Farm. Its dry raised bed, known locally as a rodham, can easily be traced in the landscape, as its light-coloured bands of silt contrast with the dark, low-lying peat soils.[20] It is also clearly shown on the modern Ordnance Survey map, delineated by the 0 ft contour.[22] On the river channel, there is a pumping station on the north bank, and the course passes between the hamlets of Brandon Bank on the north bank and Little Ouse on the south. Nearby is the lowest trig point in Britain, marking a spot which is 3 feet (0.91 m) below sea level.[23] Its junction with the Great Ouse is immediately after it passes under the A10 road.[5]

Flood precautions

.jpg.webp)

The Environment Agency has designated the section from Thetford to Brandon, where it flows through the afforested Breckland, as a Flood Warning Area.[24]

The lower part of the river crosses over the Cut-off Channel in a concrete aqueduct. The Channel is a 28-mile (45 km) drain which runs from Barton Mills to Denver along the south-eastern edge of the Fens, and was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s. During times of flood it carries the head waters of the River Lark, the River Wissey and the Little Ouse to Denver Sluice.[25] On its east side are two sluices, so that flood water from the upper river can be diverted into the Cut-off Channel and the section between there and the Great Ouse isolated. The flood banks on this lower section are up to half a mile (0.8 km) apart, so that the meandering river can form a large lake.

Nearer the mouth of the river, the Brandon Engine was the main outlet for the drainage of the northern half of Burnt Fen from 1830[26] until 1958. The original steam engine was replaced in 1892, by a new engine that could pump 75 tons per minute.[27] That engine was replaced by a 250 horse power oil engine in late 1925, supplied by Blackstone and Company, which drove a 42-inch (110 cm) Gwynne rotary pump. The pump could discharge 150 tons per minute against a head of 18 feet (5.5 m),[28] and lasted for 30 years. When a replacement was considered in the 1950s, the Commissioners of the Burnt Fen were faced with the problem that the White House Drain which supplied it had become bigger and more unstable as the ground surface had shrunk, and the engine sat at the top of a hill, rather than at the lowest point on the northern Fen. Consequently, a new electric pumping station was constructed at Whitehall on the River Great Ouse, the flow in the drain reversed, and the pumping station decommissioned.[29]

Navigation

River Little Ouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The river is currently navigable for 16.6 miles (26.7 km) from its junction with the River Great Ouse to Santon Downham bridge.[30] There are references to its use by boats carrying goods to Brandon as early as the 13th century, and barges are known to have reached Thetford, some 6 miles (9.7 km) beyond Santon Downham when the river was tidal.[31] Stone from Barnack, used in the construction of Thetford Priory in the 12th century, was almost certainly moved along the river, and improvements to the channel were authorised by the Commissioners of Sewers as early as 1575. Further documentary evidence confirms that it was navigable as far as Thetford in 1664.[32]

However, water levels dropped when Denver Sluice was built on the River Great Ouse. An Act of Parliament authorised the Corporation of Thetford to make improvements to the river in 1670, but they were unable to carry out the work, and so the Rt Hon Henry, Earl of Arlington made the improvements, and was assigned the tolls as a result.[32] A series of staunches were built, to hold back the water and raise the levels, but they were too far apart to be effective.[20] The rights of the navigation were given to Thetford Corporation by Henry's daughter Isabella in 1696, and the Corporation had to build a new staunch near Thetford in 1742, in order to maintain water levels in the town.[33]

By 1750, disputes were arising, since all the original Commissioners were dead, and they had failed to appoint replacements. A new Act of Parliament was sought and obtained in 1751, which appointed new Commissioners. Immediately, Thetford Corporation made improvements to the river, constructing staunches at Thetford, Thetford Middle, Turfpool, Croxton, Santon, Brandon and Sheepwash. An eighth staunch was built later at Crosswater, where Lakenheath Lode joins the river.[33] Staunches consisted of a gate or gates across the river, which held back the water above it, to enable boats to float over shallow sections. Their disadvantage was that the river level had to be lowered by a sluice to allow the gate to be opened. They are all labelled "Stanch" on the 1905 Ordnance Survey map.[34] A further Act was obtained in 1789, which regularised the collection of tolls on the whole river by Thetford Corporation. They rebuilt the seven staunches between 1827 and 1835, and the £955 of income received from the navigation in 1833 accounted for over 90 per cent of the total income of the Corporation.[35]

The 1770s saw a grand plan to build a canal from the Little Ouse at Thetford to the River Stort at Bishops Stortford. With a spur to Cambridge, this would have enabled goods to reach London by canal from much of East Anglia. Although the capital cost could not be justified, it was not until the 1850s and the advent of the railways that the scheme was finally abandoned.[20]

Tolls reached a record £1,728 in 1845, when over 15,000 tonnes of coal were carried, but the arrival of the railways, in the form of a line from Norwich to Brandon, and an extension of the Eastern Counties Railway from Newport to Brandon, both opened on the same day in 1845, started the rapid decline of the navigation. Tolls had fallen to £439 by 1849. The tolls were leased to private individuals from 1850, but an attempt to transfer £320 to the Council finance committee from the navigation in 1859 resulted in nearly a year of legal wrangling, and ultimately the money was repaid in 1860.[36] The state of the navigation declined steadily, although there was still commercial traffic, and a 25-foot (7.6 m) paddle steamer ran trips to Cambridge and around the local waterways in the 1880s.[37]

Repairs were again necessary in the 1890s, but with no funds available, the navigation committee asked Fisons, who ran a 50-foot (15 m) screw tug called Speedwell to tow lighters to King's Lynn, for an advance on their tolls to fund the work. This arrangement continued, and kept the navigation open for some years.[38] When Henry de Salis visited it in 1904, he reported that most of the staunches were out of order, and that it was in poor condition.[39] The Bedford Level Commissioners kept the weed removed from the lower section, and the South Level Commissioners maintained Crosswater Staunch, but commercial traffic had ceased by the start of the First World War. Responsibility for the river passed to the Great Ouse Catchment Board with the passing of the Land Drainage Act 1930, and they removed the staunches, replacing those at Thetford and at Brandon with sluices.[40] Responsibility changed again with the formation of the Environment Agency in 1995.

The navigable river is mainly on the same level, with a single lock, which was opened in 1995, at Brandon just a short distance from Brandon bridge. The lock is 13 feet (4.0 m) wide but only 39 feet (12 m) long, and so is not suitable for many narrowboats, although boats up to 79 feet (24 m) long can be turned just below the lock, which is less than 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) from Brandon village.[19]

There is a campaign to re-open the river for navigation to Thetford, and the Environment Agency commissioned consultants in 2003 to look at the feasibility of such a project. The report suggested that four locks would be required on this section.[41] The head of navigation was effectively extended in 2008 when the 2+1⁄2-mile (4 km) section from Brandon Bridge to Santon Downham was made more accessible to boaters by the construction of moorings just below Santon Downham bridge, which are now managed by the Great Ouse Boating Association. Beyond the bridge the river is only accessible to canoes and dingies, due to the presence of rocks on the river bed.[30]

Water quality

The Environment Agency measure the water quality of the river systems in England. Each is given an overall ecological status, which may be one of five levels: high, good, moderate, poor and bad. There are several components that are used to determine this, including biological status, which looks at the quantity and varieties of invertebrates, angiosperms and fish. Chemical status, which compares the concentrations of various chemicals against known safe concentrations, is rated good or fail.[42]

The water quality of the River Little Ouse system was as follows in 2019.

| Section | Ecological Status | Chemical Status | Length | Catchment | Channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Ouse (US Thelnetham)[43] | Bad | Fail | 5.4 miles (8.7 km) | 15.27 square miles (39.5 km2) | heavily modified |

| Little Ouse (Thelnetham to Hopton Common)[44] | Poor | Fail | 3.0 miles (4.8 km) | 2.46 square miles (6.4 km2) | heavily modified |

| Little Ouse (Hopton Common to Sapiston Confl)[45] | Moderate | Fail | 7.8 miles (12.6 km) | 20.70 square miles (53.6 km2) | heavily modified |

| Little Ouse (Sapiston Confluence to Nuns Br)[46] | Moderate | Fail | 4.3 miles (6.9 km) | 19.00 square miles (49.2 km2) | heavily modified |

| Little Ouse River[47] | Moderate | Fail | 12.2 miles (19.6 km) | 43.53 square miles (112.7 km2) | heavily modified |

The Environment Agency data for the upper river covers a short section of the Little Ouse, and a long section of the stream that flows northwards from Rickinghall and Botesdale. They have set a target for improving the water quality on this section from bad to poor by 2021. Like many rivers in the UK, the chemical status changed from good to fail in 2019, due to the presence of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) and perfluorooctane sulphonate (PFOS), neither of which had previously been included in the assessment.

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jn with River Great Ouse | 52°30′04″N 0°22′00″E / 52.5011°N 0.3668°E | TL607918 | |

| Lakenheath Lode | 52°26′33″N 0°27′19″E / 52.4426°N 0.4554°E | TL669855 | |

| Cut-off Channel sluices | 52°27′13″N 0°32′49″E / 52.4537°N 0.5469°E | TL731870 | |

| Brandon Lock | 52°26′57″N 0°36′57″E / 52.4493°N 0.6157°E | TL778867 | |

| Santon Downham | 52°27′31″N 0°40′24″E / 52.4586°N 0.6732°E | TL817878 | Limit of navigation |

| Abbey Heath Weir | 52°25′34″N 0°43′15″E / 52.4260°N 0.7209°E | TL850843 | |

| Jn with River Thet | 52°24′48″N 0°44′48″E / 52.4133°N 0.7468°E | TL869830 | |

| Jn with The Black Bourn | 52°23′11″N 0°46′24″E / 52.3863°N 0.7732°E | TL888800 | |

| Source of river | 52°22′16″N 0°59′39″E / 52.3712°N 0.9942°E | TM039790 |

Bibliography

- Beckett, John (1983). Urgent Hour: Drainage of the Burnt Fen District in the South Level of the Fens, 1760-1981. Ely Local History Publication Board. ISBN 978-0-904463-88-0.

- Blair, Andrew Hunter (2006). The River Great Ouse and tributaries. Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85288-943-5.

- Boyes, John; Russell, Ronald (1977). The Canals of Eastern England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7415-3.

- Thirsk, Joan (2002). Rural England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860619-2.

- West, Prof. Richard (2006). "The Frith and the Little Ouse and Waveney valley fens: origin and history" (PDF). Little Ouse Headwaters Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2017.

See also

References

- ↑ "Blo'Norton and Thelnetham Fen" (PDF). SSSI citation. Natural England. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ West 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ West 2006, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ "Geodiversity in the Little Ouse Headwaters". Little Ouse Headwaters Project. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ordnance Survey, 1:50,000 map

- ↑ "Hinderclay Fen". Little Ouse Headwaters Project. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Windmill, Thelnetham (1031207)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Garboldisham Windmill (1168497)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of All Saints (1031264)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Rushford Bridge (1003768)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Nunnery Lakes Reserve". British Trust for Ornithology. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Welcome to Nunnery Lakes Discovery Trail" (PDF). British Trust for Ornithology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Nuns Bridge South (1195912)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Nuns Bridge Central (1195911)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Nuns Bridge North (1279479)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Ellis Clarke's Memoirs - Thetford Swimming Pool". Thetford & District Rotary Club. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Town Bridge (1195954)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Thetford Forest". Forestry Commission. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Blair 2006, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 Blair 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ }"About Lakenheath Fen". RSPB. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "1:25,000 map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "The trig pillars that helped map Great Britain". BBC. 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Flood Warnings FWA Detail". Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ↑ Thirsk 2002.

- ↑ Beckett 1983, p. 22.

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 "Little Ouse River" (PDF). Easterling, The Journal of the EAWA. East Anglian Waterways Association. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ↑ Blair 2006, pp. 72–73.

- 1 2 Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 183.

- 1 2 Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 184.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1905

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 185–187.

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 188.

- ↑ Bradshaw's Canals & Navigable Rivers (1904)

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ "Little Ouse Navigation". Inland Waterways Association. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ↑ "Glossary (see Biological quality element; Chemical status; and Ecological status)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Little Ouse (US Thelnetham)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Little Ouse (Thelnetham to Hopton Common)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Little Ouse (Hopton Common to Sapiston Confl)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Little Ouse (Sapiston Confluence to Nuns Br)". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Little Ouse River". Catchment Data Explorer. Environment Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

Footnote

- Note 1: See map The old, winding course of the Great Ouse was from the bottom of the map, along the green-dotted footpath, just south of the roundabout, along the Holmes River, westwards through the northern fringe of Littleport and northwards between the two brown 0 metre contour lines, until it passed out of the top of the map.