Kingdom of Luwu | |

|---|---|

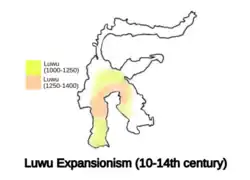

Luwu expansion on Sulawesi (1000-1400 AD) | |

| Status | Part of Indonesia |

| Capital | Malangke before c.1620 Palopo after c.1620 |

| Common languages | Bugis |

| Religion | Hinduism Buddhism, Animism prior to c.1605 Sunni Islam after 1605 |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Datu Mappanjunge' ri Luwu | |

| Currency | No official currency |

| Today part of | Indonesia (as Luwu Regency) |

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Kingdom of Luwu (also Luwuq or Wareq) was a polity located in northern part of South Sulawesi. province of Indonesia, on Sulawesi island. It is considered one of the earliest known Bugis kingdom in Sulawesi, founded between 10th and 14th century. However, recent archaeological research has challenged the idea.[1]

History

Origin of Luwu

In 1889, Dutch administrator of Makassar Braam Morris placed Luwu's peak territorial extent between the 10th and 14th centuries, but offered no clear evidence.[2] The La Galigo, an epic poem composed in a literary form of the Bugis language, is the likely inspiration of the dating. Morris' theory combined two older concepts which were already common in the region, which are (1) the so-called 'primordial age' as described within La Galigo, and (2) the widespread belief of other Bugis polities in South Sulawesi, who viewed the rulers of Luwu as the most senior lineages of all Bugis rulers. However, historians and archaeologists expressed doubts regarding these claims. They noted that any historical records and chronologies of Luwu were 'disappointingly shallow' and 'absent of any evidence'.[1]

Meanwhile, the Bugis world described in La Galigo depicted a vaguely defined world of coastal and riverine kingdoms whose economies are based on trade. Two early centers of this world were Luwu and the kingdom of Cina (pronounced Cheena) in what is now Wajo. The incompatibility of the La Galigo's trade-based political economy with the agricultural economies of other South Sulawesi kingdoms has led scholars to posit an intervening period of chaos to separate the two societies chronologically.[3] Archaeological and textual research carried out since the 1980s has undermined this chronology, however.[4] Extensive surveys and excavations in Luwu have revealed that the Bugis-speaking kingdom is a century or so younger than the oldest polities of the southwest peninsula.[5] The earliest textual reference to Luwu is in the Majapahit court poem Desawarnana (c.1365), which listed Luwu, Bantaeng in southern part of the island, and Uda (possibly Cina) as the three major powers on the peninsula. However, there are no convincing archaeological evidence of Bugis settlement in Luwu region before c.1300.

The new understanding is that Bugis speaking settlers from the western Cenrana valley began to settle along the coastal margins of Luwu around the year 1300 CE. The Gulf of Bone is not a merely Bugis-speaking area only: it is a thinly populated region of great ethnic diversity in which Bugis speakers are a minority among the speakers of Pamona, Padoe, Wotu and Lemolang languages who lived on the coastal lowlands and foothills, while the highland valleys are home to groups speaking other Central and South Sulawesi languages. The Bugis are found almost solely along the coast, to which they have evidently migrated in order to trade with Luwu's indigenous peoples. It is clear both from archaeological and textual sources that Luwu was a Bugis-led coalition of various ethnic groups, united by trade relationships and by the ability of the Datu' (ruler) of Luwu to enforce peace among neighboring hill tribes. The main centres of Bugis settlement were (and still are) Bua, Ponrang, Malangke, and Cerekang near Malili.

The migration of Bugis from the central lakes area to Luwu was evidently lead by members of Cina's ruling family, a loose coalition of high-ranking families claiming a common ancestry that ruled settlements across the Cenrana and Walennae valleys. This can be surmised from the fact that Luwu and Cina share the same founding myth of a tomanurung or heavenly-descended being called Simpurusia, and that both versions of this myth state that Simpurusia descended at Lompo, in Sengkang. Cina was absorbed in the 16th century by its former tributaries of Soppeng and Wajo, after which its ruling family effectively vanished. However, the ancient line of Cina's rulers are believed to continue in Luwu until the abolition of the kingdoms in 1954. It is likely that the widespread belief that Luwu is older than other South Sulawesi kingdoms stems partly from this illustrious lineage and accounts for the precedence today of the Datu of Luwu over all the former polities of South Sulawesi.

Luwu's political economy was based on the smelting of iron ore brought down, via the Lemolang-speaking polity of Baebunta, to Malangke on the central coastal plain. The smelted iron was worked into weapons and agricultural tools and exported to the rice-growing southern lowlands. This brought the kingdom great wealth, and by the mid-14th century Luwu had become the feared overlord of large parts of the southwest and southeast peninsula. The earliest identifiable ruler is Bataraguru (mid-15th century) whose name appears in a peace treaty with Bone. However, the first ruler for which we have any detailed information was Dewaraja (ruled c. 1495-1520). Stories current today in South Sulawesi tell of his aggressive attacks on the neighboring kingdoms of Wajo and Sidenreng. Luwu's power was eclipsed in the 16th century by the rising power of the southern agrarian kingdoms, and its military defeats are set out in the Chronicle of Bone.

Islamic Luwu

On 4 or 5 February 1605, Luwu's ruler, La Patiwareq, Daeng Pareqbung, became the first major South Sulawesi ruler to embrace Islam, taking as his title Sultan Muhammad Wali Mu’z’hir (or Muzahir) al-din.[6] La Patiwareq is buried at Malangke and is referred to in the chronicles as Matinroe ri Wareq, ‘He who sleeps at Wareq’, the former palace-centre of Luwuq. His religious teacher, Dato Sulaiman, is buried nearby. Around 1620, Malangke was abandoned and a new capital was established to the west at Palopo. It is not known why this sprawling settlement, the population of which may have reached 15,000 in the 16th century, was suddenly abandoned: possibilities include religious turmoil, the declining price of iron goods and the economic potential of trade with the Toraja highlands.

Colonial Luwu

By the 19th century, Luwu had become a backwater. James Brooke, later Rajah of Sarawak, wrote in the 1830s that ‘Luwu is the oldest Bugis state, and the most decayed. [...] Palopo is a miserable town, consisting of about 300 houses, scattered and dilapidated. [...] It is difficult to believe that Luwu could ever have been a powerful state, except in a very low state of native civilisation.’[7]

Present-day Luwu

In the 1960s Luwu was a focus of an Islamic rebellion led by Kahar Muzakkar. Today the former kingdom is home to the world's largest nickel mine and is experiencing an economic boom fueled by inward migration, yet it still retains much of its original frontier atmosphere.

Economy

Unlike other Bugis polities in South Sulawesi which based its economy on rice production and trade, Luwu was known to be a center of metalwork, especially iron, whose ore were both imported and extracted locally iron ore. Luwu's prestige, which came through iron mining activities and ironware exports in the past, led to the island on which Luwu existed to be known as Sulawesi, or 'iron island'.[8]

In addition, Luwu seemed to base its economy on arboriculture (or forest produces) exports. Dammar gum, rattan, ebony, gaharu, and mangrove timbers were thought as resources extracted upland, then exported via Luwu's port on the Gulf of Bone.

Rulers of Luwu

Rulers of Luwu used the title Datu Mappanjunge' ri Luwu which means "Datu that umbrellaing Luwu" or "Datu that covered Luwu", shortened to Datu Luwu, Pajung Luwu, or Pajunge'.

See also

References

- 1 2 Bulbeck, David; Prasetyo, Bagyo (1998). "Survey of Pre-Islamic Historical Sites in Luwu, South Sulawesi". Walennae. 1: 29.

- ↑ Morris, D. F. van Braam (1992). Kerajaan Luwu: menurut catatan D.F. van Braam Morris (in Indonesian). Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Balai Kajian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional.

- ↑ Pelras, C. 1996. The Bugis. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ↑ Bulbeck, D. and I. Caldwell. 2000. Land of iron; The historical archaeology of Luwu and the Cenrana valley. Hull: Centre for South East Asian Studies, University of Hull.

- ↑ David Bulbeck and Ian Caldwell, Land of iron: The historical archeology of Luwu and the Cenrana valley. Results of the Origins of Complex Society in South Sulawesi Project (OXIS). Centre for South-East Asian Studies Occasional Publications Series, University of Hull.

- ↑ SILA, MUHAMMAD ADLIN (2015). "The Lontara'". The Lontara':: The Bugis-Makassar Manuscripts and their Histories. A Way of Union with God. ANU Press. pp. 27–40. ISBN 978-1-925022-70-4. JSTOR j.ctt19893ms.10. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Brooke, J. 1848. Narrative of events in Borneo and Celebes down to the occupation of Labuan. From the Journals of James Brooke, Esq. Rajah of Sarawak and Governor of Labuan [. . .] by Captain Rodney Mundy. London: John Murray.

- ↑ Bulbeck, David (2000). "Economy, Military and Ideology in Pre-Islamic Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia" (PDF). Australasian Historical Archaeology. 18.