Des Moines | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): | |

Location within Iowa | |

Des Moines Location in Iowa  Des Moines Location in the United States  Des Moines Des Moines (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 41°35′27″N 93°37′15″W / 41.59083°N 93.62083°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Polk, Warren |

| Founded | 1843 |

| Incorporated | September 22, 1851 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[3] |

| • Body | Des Moines City Council |

| • Mayor | Frank Cownie (D) |

| • Senate | Senate list |

| • House | House list |

| • U.S. Congress | Zach Nunn (R) |

| Area | |

| • State capital city | 90.70 sq mi (234.92 km2) |

| • Land | 88.18 sq mi (228.38 km2) |

| • Water | 2.52 sq mi (6.54 km2) |

| Elevation | 873 ft (266 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • State capital city | 214,133 |

| • Rank | US: 111th IA: 1st |

| • Density | 2,428.39/sq mi (937.60/km2) |

| • Urban | 542,486 (US: 78th) |

| • Urban density | 2,413.8/sq mi (932.0/km2) |

| • Metro | 709,466 (US: 81st) |

| • CSA | 890,322 (US: 65th) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 50301-50340-50310-50316 |

| Area code | 515 |

| FIPS code | 19-21000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 465961 |

| Website | www |

Des Moines (/dəˈmɔɪn/ ⓘ) is the capital and the most populous city in Iowa, United States. It is also the county seat of Polk County. A small part of the city extends into Warren County. It was incorporated on September 22, 1851, as Fort Des Moines, which was shortened to "Des Moines" in 1857.[6] It is located on, and named after, the Des Moines River, which likely was adapted from the early French name, Rivière des Moines, meaning "River of the Monks". The city's population was 214,133 as of the 2020 census.[7] The six-county metropolitan area is ranked 81st in terms of population in the United States, with 709,466 residents according to the 2020 census by the United States Census Bureau, and is the largest metropolitan area fully located within the state.[8]

Des Moines is a major center of the US insurance industry and has a sizable financial-services and publishing business base. The city was credited as the "number one spot for U.S. insurance companies" in a Business Wire article and named the third-largest "insurance capital" of the world. The city is the headquarters for the Principal Financial Group, Ruan Transportation, TMC Transportation, EMC Insurance Companies, and Wellmark Blue Cross Blue Shield. Other major corporations such as Wells Fargo, Cognizant, Voya Financial, Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company, ACE Limited, Marsh, Monsanto, and Corteva have large operations in or near the metropolitan area. In recent years, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, and Facebook[9][10] have built data-processing and logistical facilities in the Des Moines area.

Des Moines is an important city in U.S. presidential politics; as the state's capital, it is the site of the first caucuses of the presidential primary cycle. Many presidential candidates set up campaign headquarters in Des Moines. A 2007 article in The New York Times said, "If you have any desire to witness presidential candidates in the most close-up and intimate of settings, there is arguably no better place to go than Des Moines."[11]

History

Etymology

Des Moines takes its name from Fort Des Moines (1843–46), which was named for the Des Moines River. This was adopted from the name given by French colonists. Des Moines (pronounced [de mwan] ⓘ; formerly [de mwɛn]) translates literally to either "from the monks" or "of the monks".

One popular interpretation of "Des Moines" concludes that it refers to a group of French Trappist monks, who in the 17th century lived in huts built on top of what is now known as the ancient Monks Mound at Cahokia, the major center of Mississippian culture, which developed in what is present-day Illinois, east of the Mississippi River and the city of St. Louis. This was some 200 miles (320 km) from the Des Moines River.[12]

Prehistoric inhabitants of early Des Moines

Based on archaeological evidence, the junction of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers has attracted humans for at least 7,000 years. Several prehistoric occupation areas have been identified by archaeologists in downtown Des Moines. Discovered in December 2010, the "Palace" is an expansive, 7,000-year-old site found during excavations prior to construction of the new wastewater treatment plant in southeastern Des Moines. It contains well-preserved house deposits and numerous graves. More than 6,000 artifacts were found at this site. State of Iowa archaeologist John Doershuk was assisted by University of Iowa archaeologists at this dig.[14]

At least three Late Prehistoric villages, dating from about AD 1300 to 1700, stood in or near what developed later as downtown Des Moines. In addition, 15 to 18 prehistoric American Indian mounds were observed in this area by early settlers. All have been destroyed during development of the city.[15][16]

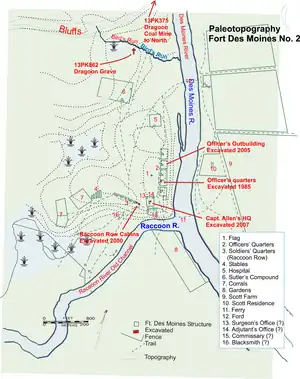

Origin of Fort Des Moines

Des Moines traces its origins to May 1843, when Captain James Allen supervised the construction of a fort on the site where the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers merge. Allen wanted to use the name Fort Raccoon; however, the U.S. War Department preferred Fort Des Moines. The fort was built to control the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes, whom the government had moved to the area from their traditional lands in eastern Iowa. The fort was abandoned in 1846 after the Sauk and Meskwaki were removed from the state and shifted to the Indian Territory.[17]

The Sauk and Meskwaki did not fare well in Des Moines. The illegal whiskey trade, combined with the destruction of traditional lifeways, led to severe problems for their society. One newspaper reported:

"It is a fact that the location of Fort Des Moines among the Sac and Fox Indians (under its present commander) for the last two years, had corrupted them more and lowered them deeper in the scale of vice and degradation, than all their intercourse with the whites for the ten years previous".[17]

After official removal, the Meskwaki continued to return to Des Moines until around 1857.[16]

Archaeological excavations have shown that many fort-related features survived under what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Parkway and First Street.[17][18] Soldiers stationed at Fort Des Moines opened the first coal mines in the area, mining coal from the riverbank for the fort's blacksmith.[19]

Early, non-Native American, settlement

Settlers occupied the abandoned fort and nearby areas. On May 25, 1846, the state legislature designated Fort Des Moines as the seat of Polk County. Arozina Perkins, a school teacher who spent the winter of 1850–1851 in the town of Fort Des Moines, was not favorably impressed:

This is one of the strangest looking "cities" I ever saw... This town is at the juncture of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers. It is mostly a level prairie with a few swells or hills around it. We have a court house of "brick" and one church, a plain, framed building belonging to the Methodists. There are two taverns here, one of which has a most important little bell that rings together some fifty boarders. I cannot tell you how many dwellings there are, for I have not counted them; some are of logs, some of brick, some framed, and some are the remains of the old dragoon houses... The people support two papers and there are several dry goods shops. I have been into but four of them... Society is as varied as the buildings are. There are people from nearly every state, and Dutch, Swedes, etc.[20]

In May 1851, much of the town was destroyed during the Flood of 1851. "The Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers rose to an unprecedented height, inundating the entire country east of the Des Moines River. Crops were utterly destroyed, houses and fences swept away."[21] The city started to rebuild from scratch.

Era of growth

On September 22, 1851, Des Moines was incorporated as a city; the charter was approved by voters on October 18. In 1857, the name "Fort Des Moines" was shortened to "Des Moines", and it was designated as the second state capital, previously at Iowa City. Growth was slow during the Civil War period, but the city exploded in size and importance after a railroad link was completed in 1866.[22]

In 1864, the Des Moines Coal Company was organized to begin the first systematic mining in the region. Its first mine, north of town on the river's west side, was exhausted by 1873. The Black Diamond mine, near the south end of the West Seventh Street Bridge, sank a 150-foot (46 m) mine shaft to reach a 5-foot-thick (1.5 m) coal bed. By 1876, this mine employed 150 men and shipped 20 carloads of coal per day. By 1885, numerous mine shafts were within the city limits, and mining began to spread into the surrounding countryside. By 1893, 23 mines were in the region.[23] By 1908, Des Moines' coal resources were largely exhausted.[24] In 1912, Des Moines still had eight locals of the United Mine Workers union, representing 1,410 miners.[25] This was about 1.7% of the city's population in 1910.

By 1880, Des Moines had a population of 22,408, making it Iowa's largest city. It displaced the three Mississippi River ports: Burlington, Dubuque, and Davenport, that had alternated holding the position since the territorial period. Des Moines has remained Iowa's most populous city. In 1910, the Census Bureau reported Des Moines' population as 97.3% white and 2.7% black, reflecting its early settlement pattern primarily by ethnic Europeans.[26]

"City Beautiful" project, decline and rebirth

At the turn of the 20th century, encouraged by the Civic Committee of the Des Moines Women's Club, Des Moines undertook a "City Beautiful" project in which large Beaux Arts public buildings and fountains were constructed along the Des Moines River. The former Des Moines Public Library building (now the home of the World Food Prize); the United States central Post Office, built by the federal government (now the Polk County Administrative Building, with a newer addition); and the City Hall are surviving examples of the 1900–1910 buildings. They form the Civic Center Historic District.

The ornate riverfront balustrades that line the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers were built by the federal Civilian Conservation Corps in the mid-1930s, during the Great Depression under Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt, as a project to provide local employment and improve infrastructure. The ornamental fountains that stood along the riverbank were buried in the 1950s when the city began a postindustrial decline that lasted until the late 1980s.[28][29] The city has since rebounded, transforming from a blue-collar industrial city to a white-collar professional city.

July 19, 1993

In 1907, the city adopted a city commission government known as the Des Moines Plan, comprising an elected mayor and four commissioners, all elected at-large, who were responsible for public works, public property, public safety, and finance. Considered progressive at the time, it diluted the votes of ethnic and national minorities, who generally could not command the majority to elect a candidate of their choice.

That form of government was scrapped in 1950 in favor of a council-manager government, with the council members elected at-large. In 1967, the city changed its government to elect four of the seven city council members from single-member districts or wards, rather than at-large. This enabled a broader representation of voters. As with many major urban areas, the city core began losing population to the suburbs in the 1960s (the peak population of 208,982 was recorded in 1960), as highway construction led to new residential construction outside the city. The population was 198,682 in 2000 and grew slightly to 200,538 in 2009.[30] The growth of the outlying suburbs has continued, and the overall metropolitan-area population is over 700,000 today.

During the Great Flood of 1993, heavy rains throughout June and early July caused the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers to rise above flood stage levels. The Des Moines Water Works was submerged by floodwaters during the early morning hours of July 11, 1993, leaving an estimated 250,000 people without running water for 12 days and without drinking water for 20 days. Des Moines suffered major flooding again in June 2008 with a major levee breach.[31] The Des Moines river is controlled upstream by Saylorville Reservoir. In both 1993 and 2008, the flooding river overtopped the reservoir spillway.

Today, Des Moines is a member of ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability USA. Through ICLEI, Des Moines has implemented "The Tomorrow Plan", a regional plan focused on developing central Iowa in a sustainable fashion, centrally-planned growth, and resource consumption to manage the local population.[32]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 90.65 square miles (234.78 km2),[33] of which 88.93 square miles (230.33 km2) is land and 1.73 square miles (4.48 km2) is covered by water.[34] It is 850 feet (260 m) above sea level at the confluence of the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers.

In November 2005, Des Moines voters approved a measure that allowed the city to annex parcels of land in the northeast, southeast, and southern corners of Des Moines without agreement by local residents, particularly areas bordering the Iowa Highway 5/U.S. 65 bypass. The annexations became official on June 26, 2009, as 5,174 acres (20.94 km2) and around 868 new residents were added to the city of Des Moines.[35] An additional 759 acres (3.07 km2) were voluntarily annexed to the city over that same period.[35]

Metropolitan area

Cityscape

The skyline of Des Moines changed in the 1970s and the 1980s, when several new skyscrapers were built. Additional skyscrapers were built in the 1990s, including Iowa's tallest. Before then, the 19-story Equitable Building, from 1924, was the tallest building in the city and the tallest building in Iowa. The 25-story Financial Center was completed in 1973 and the 36-story Ruan Center was completed in 1974. They were later joined by the 33-story Des Moines Marriott Hotel (1981), the 25-story HUB Tower and 25-story Plaza Building (1985). Iowa's tallest building, Principal Financial Group's 45-story tower at 801 Grand was built in 1991, and the 19-story EMC Insurance Building was erected in 1997.

During this time period, the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines (1979) was developed; it hosts Broadway shows and special events. Also constructed were the Greater Des Moines Botanical Garden (1979), a large city botanical garden/greenhouse on the east side of the river; the Polk County Convention Complex (1985), and the State of Iowa Historical Museum (1987). The Des Moines skywalk also began to take shape during the 1980s. The skywalk system is 4 miles (6.4 km) long and connects many downtown buildings.[36][37]

In the early 21st century, the city has had more major construction in the downtown area. The new Science Center of Iowa and Blank IMAX Dome Theater and the Iowa Events Center opened in 2005. The new central branch of the Des Moines Public Library, designed by renowned architect David Chipperfield of London, opened on April 8, 2006.

The World Food Prize Foundation, which is based in Des Moines, completed adaptation and restoration of the former Des Moines Public Library building in October 2011. The former library now serves as the home and headquarters of the Norman Borlaug/World Food Prize Hall of Laureates.

Climate

At the center of North America and far removed from large bodies of water, the Des Moines area has a hot summer type humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), with warm to hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. Summer temperatures can often climb into the 90 °F (32 °C) range, occasionally reaching 100 °F (38 °C). Humidity can be high in spring and summer, with frequent afternoon thunderstorms. Fall brings pleasant temperatures and colorful fall foliage. Winters vary from moderately cold to bitterly cold, with low temperatures venturing below 0 °F (−18 °C) quite often. Snowfall averages 36.5 inches (93 cm) per season, and annual precipitation averages 36.55 inches (928 mm), with a peak in the warmer months. Winters are slightly colder than Chicago, but still warmer than Minneapolis, with summer temperatures being very similar between the Upper Midwest metropolitan areas.

| Climate data for Des Moines International Airport, Iowa (1991–2020 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1878–present[lower-alpha 2]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

78 (26) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

110 (43) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

82 (28) |

74 (23) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.4 (11.9) |

58.7 (14.8) |

74.6 (23.7) |

83.9 (28.8) |

88.9 (31.6) |

93.1 (33.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

94.4 (34.7) |

91.3 (32.9) |

83.3 (28.5) |

70.4 (21.3) |

57.8 (14.3) |

97.4 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.9 (−0.6) |

35.7 (2.1) |

49.2 (9.6) |

62.0 (16.7) |

72.4 (22.4) |

81.9 (27.7) |

85.6 (29.8) |

83.6 (28.7) |

76.9 (24.9) |

63.4 (17.4) |

48.3 (9.1) |

35.9 (2.2) |

60.5 (15.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

39.4 (4.1) |

51.3 (10.7) |

62.4 (16.9) |

72.2 (22.3) |

76.0 (24.4) |

73.9 (23.3) |

66.2 (19.0) |

53.2 (11.8) |

39.3 (4.1) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

50.9 (10.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 13.8 (−10.1) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

40.6 (4.8) |

52.3 (11.3) |

62.4 (16.9) |

66.4 (19.1) |

64.2 (17.9) |

55.4 (13.0) |

42.9 (6.1) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

41.3 (5.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7.8 (−22.1) |

−2.7 (−19.3) |

9.2 (−12.7) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

50.2 (10.1) |

56.9 (13.8) |

54.8 (12.7) |

40.4 (4.7) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

−1.2 (−18.4) |

−11.4 (−24.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −30 (−34) |

−26 (−32) |

−22 (−30) |

9 (−13) |

26 (−3) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

40 (4) |

26 (−3) |

7 (−14) |

−10 (−23) |

−22 (−30) |

−30 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.08 (27) |

1.34 (34) |

2.17 (55) |

4.02 (102) |

5.24 (133) |

5.26 (134) |

3.82 (97) |

4.17 (106) |

3.18 (81) |

2.78 (71) |

1.91 (49) |

1.58 (40) |

36.55 (928) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.4 (24) |

10.2 (26) |

4.4 (11) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

2.7 (6.9) |

7.9 (20) |

36.5 (93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.2 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 12.7 | 11.7 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 113.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.9 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 5.6 | 25.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.0 | 71.3 | 67.9 | 63.2 | 63.0 | 64.8 | 67.7 | 70.0 | 70.9 | 66.5 | 71.0 | 74.6 | 68.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 157.7 | 163.3 | 206.0 | 222.2 | 276.0 | 312.1 | 337.8 | 297.9 | 239.8 | 210.0 | 138.5 | 129.2 | 2,690.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 61 | 69 | 73 | 70 | 64 | 61 | 47 | 45 | 60 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[38][39][40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[41] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 502 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,965 | 689.8% | |

| 1870 | 12,035 | 203.5% | |

| 1880 | 22,408 | 86.2% | |

| 1890 | 50,093 | 123.5% | |

| 1900 | 62,139 | 24.0% | |

| 1910 | 86,368 | 39.0% | |

| 1920 | 126,468 | 46.4% | |

| 1930 | 142,559 | 12.7% | |

| 1940 | 159,819 | 12.1% | |

| 1950 | 177,965 | 11.4% | |

| 1960 | 208,982 | 17.4% | |

| 1970 | 201,404 | −3.6% | |

| 1980 | 191,003 | −5.2% | |

| 1990 | 193,187 | 1.1% | |

| 2000 | 198,682 | 2.8% | |

| 2010 | 203,433 | 2.4% | |

| 2020 | 214,133 | 5.3% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 212,031 | −1.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[42][7] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020[7] | 2010[43] | 1990[26] | 1970[26] | 1950[26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 64.5% | 76.4% | 89.2% | 93.8% | 95.4% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 61.0% | 70.5% | 87.8% | 92.7%[lower-alpha 3] | N/A |

| Black or African American | 11.7% | 10.2% | 7.1% | 5.7% | 4.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 15.6% | 12.0% | 2.4% | 1.3%[lower-alpha 3] | N/A |

| Asian | 6.8% | 4.4% | 2.4% | 0.2% | − |

2020 census

| Race or Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) |

Race Alone | Total [lower-alpha 4] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 61.0% | 65.1% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[lower-alpha 5] | — | 15.6% | ||

| African American (NH) | 11.5% | 13.6% | ||

| Asian (NH) | 6.7% | 7.6% | ||

| Native American (NH) | 0.3% | 1.5% | ||

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 0.06% | 0.2% | ||

| Other | 0.4% | 1.2% | ||

As of the census of 2020,[45] the population was 214,133. The population density was 2,428.4 per square mile (937.6/km2). There were 93,052 housing units at an average density of 1,055.3 per square mile (407.4/km2). The racial makeup was 64.54% (138,200) white, 11.68% (25,011) black or African-American, 0.69% (1,474) Native American, 6.76% (14,474) Asian, 0.06% (135) Pacific Islander, 6.62% (14,178) from other races, and 9.65% (20,661) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 14.0% (30,105) of the population.

The 2020 census population of the city included 252 people incarcerated in adult correctional facilities and 2,378 people in student housing.[46]

According to the American Community Survey estimates for 2016–2020, the median income for a household in the city was $54,843, and the median income for a family was $66,420. Male full-time workers had a median income of $47,048 versus $40,290 for female workers. The per capita income for the city was $29,064. About 12.1% of families and 16.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.3% of those under age 18 and 9.8% of those age 65 or over.[47] Of the population age 25 and over, 86.7% were high school graduates or higher and 27.9% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[48]

2010 census

.png.webp)

As of the census of 2010, there were 203,433 people, 81,369 households, and 47,491 families residing in the city.[49] Population density was 2,515.6 inhabitants per square mile (971.3/km2). There were 88,729 housing units at an average density of 1,097.2 per square mile (423.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city for Unincorporated areas not merged with the city proper was 66.2% White, 15.5% African Americans, 0.5% Native American, 4.0% Asian, and 2.6% from Two or more races. People of Hispanic or Latino origin, of any race, made up 12.1% of the population. The city's racial make up during the 2010 census was 76.4% White, 10.2% African American, 0.5% Native American, 4.4% Asian (1.2% Vietnamese, 0.9% Laotian, 0.4% Burmese, 0.3% Asian Indian, 0.3% Thai, 0.2% Chinese, 0.2% Cambodian, 0.2% Filipino, 0.1% Hmong, 0.1% Korean, 0.1% Nepalese), 0.1% Pacific Islander, 5.0% from other races, and 3.4% from two or more races. People of Hispanic or Latino origin, of any race, formed 12.0% of the population (9.4% Mexican, 0.7% Salvadoran, 0.3% Guatemalan, 0.3% Puerto Rican, 0.1% Honduran, 0.1% Ecuadorian, 0.1% Cuban, 0.1% Spaniard, 0.1% Spanish). Non-Hispanic Whites were 70.5% of the population in 2010.[43] Des Moines also has a sizeable South Sudanese community.[50]

There were 81,369 households, of which 31.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.9% were married couples living together, 14.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 41.6% were non-families. 32.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.11.

The median age in the city was 33.5 years. 24.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.4% were from 25 to 44; 23.9% were from 45 to 64; and 11% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.9% male and 51.1% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 198,682 people, 80,504 households, and 48,704 families in the city.[51] The population density was 2,621.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,012.1/km2). There were 85,067 housing units at an average density of 1,122.3 per square mile (433.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 82.3% white, 8.07% Black, 0.35% American Indian, 3.50% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 3.52% from other races, and 2.23% from two or more races. 6.61% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 20.9% were of German, 10.3% Irish, 9.1% "American" and 8.0% English ancestry, according to Census 2000.

There were 80,504 households, out of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.7% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.5% were non-families. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 3.04.

The age distribution was 24.8% under the age of 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 31.8% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 12.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $38,408, and the median income for a family was $46,590. Males had a median income of $31,712 versus $25,832 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,467. About 7.9% of families and 11.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.9% of those under age 18 and 7.6% of those ages 65 or over.

Economy

| Rank | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wells Fargo & Co. | 13,500 |

| 2 | UnityPoint Health | 8,026 |

| 3 | Principal Financial Group | 6,600 |

| 4 | MercyOne | 4,276 |

| 5 | Amazon | 3,500 |

| 6 | Nationwide/Allied Insurance | 3,300 |

| 7 | John Deere | 2,884 |

| 8 | Corteva | 2,500 |

| 9 | UPS | 1,721 |

| 10 | Wellmark Blue Cross Blue Shield | 1,600 |

Many insurance companies are headquartered in Des Moines, including the Principal Financial Group, EMC Insurance Group, Fidelity & Guaranty Life, Allied Insurance, GuideOne Insurance, Wellmark Blue Cross Blue Shield of Iowa, FBL Financial Group, and American Republic Insurance Company. Iowa has one of the lowest insurance premium taxes in the nation at 1%, and does not charge any premium taxes on qualified life insurance plans, making the state attractive to insurance business.[53] Des Moines has been referred to as the "Hartford of the West" and "Insurance Capital" because of this.[54][55] Principal is one of two Fortune 500 companies with headquarters in Iowa (the other being Casey's General Stores), ranking 201st on the magazine's list in 2020.[56]

As a center of financial and insurance services, other major corporations headquartered outside of Iowa have a presence in the Des Moines Metro area, including Wells Fargo, Voya Financial, and Electronic Data Systems (EDS). The Meredith Corporation, a leading publishing and marketing company, was also based in Des Moines prior to its acquisition by IAC and merger with Dotdash in 2021. Meredith published Better Homes and Gardens, one of the most widely circulated publications in the United States. Des Moines was also the headquarters of Golf Digest magazine.

Other major employers in Des Moines include UnityPoint Health, Mercy Medical Center, MidAmerican Energy Company, CDS Global, UPS, Firestone Agricultural Tire Company, EDS, Drake University, Titan Tire, The Des Moines Register, Anderson Erickson, Dee Zee and EMCO.[57]

In 2017, Kemin Industries opened a state-of-the-art worldwide headquarters building in Des Moines.[58]

Arts and culture

Arts and theater

The City of Des Moines is a cultural center for Iowa and home to several art and history museums and performing arts groups. The Des Moines Performing Arts routinely hosts touring Broadway shows and other live professional theater. Its president and CEO, Jeff Chelsvig, is a member of the League of American Theatres and Producers, Inc. The Temple for Performing Arts and Des Moines Playhouse are other venues for live theater, comedy, and performance arts.

The Des Moines Metro Opera has been a cultural resource in Des Moines since 1973. The Opera offers educational and outreach programs and is one of the largest performing arts organizations in the state. Ballet Des Moines was established in 2002. Performing three productions each year, the Ballet also provides opportunities for education and outreach.

The Des Moines Symphony performs frequently at different venues. In addition to performing seven pairs of classical concerts each season, the Symphony also entertains with New Year's Eve Pops and its annual Yankee Doodle Pops concerts.

Jazz in July[59] is an annual event founded in 1969 that performs free jazz shows daily at venues throughout the city during July.

Wells Fargo Arena is the Des Moines area's primary venue for sporting events and concerts since its opening in 2005. Named for title sponsor Wells Fargo Financial Services, Wells Fargo Arena holds 16,980 and books large, national touring acts for arena concert performances, while several smaller venues host local, regional, and national bands. It is the home of the Iowa Wolves of the NBA G League, the Iowa Wild of the American Hockey League, and the Iowa Barnstormers of the Indoor Football League.

The Simon Estes Riverfront Amphitheater is an outdoor concert venue on the east bank of the Des Moines River which hosts music events such as the Alive Concert Series.

The Des Moines Art Center, with a wing designed by architect I. M. Pei, presents art exhibitions and educational programs as well as studio art classes. The Center houses a collection of artwork from the 19th century to the present. An extension of the art center is downtown in an urban museum space, featuring three or four exhibitions each year.

The Pappajohn Sculpture Park was established in 2009. It showcases a collection of 24 sculptures donated by Des Moines philanthropists John and Mary Pappajohn. Nearby is the Temple for Performing Arts, a cultural center for the city. Next to the Temple is the 117,000-square-foot (10,900 m2) Central Library, designed by renowned English architect David Chipperfield.

Salisbury House and Gardens is a 42-room historic house museum on 10 acres (4 ha) of woodlands in the South of Grand neighborhood of Des Moines. It is named after—and loosely inspired by—King's House in Salisbury, England. Built in the 1920s by cosmetics magnate Carl Weeks and his wife, Edith, the Salisbury House contains authentic 16th-century English oak and rafters dating to Shakespeare's days, numerous other architectural features re-purposed from other historic English homes, and an internationally significant collection of original fine art, tapestries, decorative art, furniture, musical instruments, and rare books and documents. The Salisbury House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and has been featured on A&E's America's Castles and PBS's Antiques Roadshow. Prominent artists in the Salisbury House collection include Joseph Stella, Lillian Genth, Anthony van Dyck and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Built in 1877 by prominent pioneer businessman Hoyt Sherman, Hoyt Sherman Place mansion was Des Moines' first public art gallery and houses a distinctive collection of 19th and 20th century artwork. Its restored 1,250-seat theater features an intricate rococo plaster ceiling and excellent acoustics and is used for a variety of cultural performances and entertainment.

Attractions

Arising in the east and facing westward toward downtown, the Iowa State Capitol building with its 275-foot (84 m), 23-karat gold leafed dome towering above the city is a favorite of sightseers. Four smaller domes flank the main dome. The Capitol houses the governor's offices, legislature, and the old Supreme Court Chambers. The ornate interior also features a grand staircase, mural "Westward", five-story law library, scale model of the USS Iowa, and collection of first lady dolls. Guided tours are available.

The Capitol grounds include a World War II memorial with sculpture and Wall of Memories, the 1894 Soldiers and Sailors Monument of the Civil War and memorials honoring those who served in the Spanish–American, Korean, and Vietnam Wars. The West Capitol Terrace provides the entrance from the west to the state's grandest building, the State Capitol Building. The 10-acre (4 ha) "people's park" at the foot of the Capitol complex includes a promenade and landscaped gardens, in addition to providing public space for rallies and special events. A granite map of Iowa depicting all 99 counties rests at the base of the terrace and has become an attraction for in-state visitors, many of whom walk over the map to find their home county.

Iowa's history lives on in the State of Iowa Historical Museum. This modern granite and glass structure at the foot of the State Capitol Building houses permanent and temporary exhibits exploring the people, places, events, and issues of Iowa's past. The showcase includes native wildlife, American Indian and pioneer artifacts, and political and military items. The museum features a genealogy and Iowa history library, museum gift shop, and cafe.

Terrace Hill, a National Historic Landmark and Iowa Governor's Residence, is among the best examples of American Victorian Second Empire architecture. This opulent 1869 home was built by Iowa's first millionaire, Benjamin F. Allen, and restored to the late 19th century period. It overlooks downtown Des Moines and is situated on 8 acres (3.2 ha) with a re-created Victorian formal garden. Tours are conducted Tuesdays through Saturdays from March through December.

The 110,000-square-foot (10,000 m2) Science Center of Iowa and Blank IMAX Dome Theater offers seven interactive learning areas, live programs, and hands-on activities encouraging learning and fun for all ages. Among its three theaters include the 216-seat Blank IMAX Dome Theater, 175-seat John Deere Adventure Theater featuring live performances, and a 50-foot (15 m) domed Star Theater.

The Greater Des Moines Botanical Garden, an indoor conservatory of over 15,000 exotic plants, is one of the largest collections of tropical, subtropical, and desert-growing plants in the Midwest. The Center blooms with thousands of flowers year-round. Nearby are the Robert D. Ray Asian Gardens and Pavilion, named in honor of the former governor whose influence helped relocate thousands of Vietnamese refugees to Iowa homes in the 1970s and 1980s. Developed by the city's Asian community, the Gardens include a three-story Chinese pavilion, bonsai landscaping, and granite sculptures to highlight the importance of diversity and recognize Asian American contributions in Iowa.

Blank Park Zoo is a landscaped 22-acre (8.9 ha) zoological park on the south side. Among the exhibits include a tropical rain forest, Australian Outback, and Africa. The Zoo offers education classes, tours, and rental facilities.

The Iowa Primate Learning Sanctuary was established as a scientific research facility with a 230-acre (93 ha) campus housing bonobos and orangutans for the noninvasive interdisciplinary study of their cognitive and communicative capabilities.

The East Village, on the east side of the Des Moines River, begins at the river and extends about five blocks east to the State Capitol Building, offering an eclectic blend of historic buildings, hip eateries, boutiques, art galleries, and a wide variety of other retail establishments mixed with residences.

Adventureland Park is an amusement park in neighboring Altoona, just northeast of Des Moines. The park boasts more than 100 rides, shows, and attractions, including six rollercoasters. A hotel and campground is just outside the park. Also in Altoona is Prairie Meadows Racetrack and Casino, an entertainment venue for gambling and horse racing. Open 24 hours a day, year-round, the racetrack and casino features live racing, plus over 1,750 slot machines, table games, and concert and show entertainment. The racetrack hosts two Grade III races annually, the Iowa Oaks and the Cornhusker Handicap.

Living History Farms in suburban Urbandale tells the story of Midwestern agriculture and rural life in a 500-acre (2.0 km2) open-air museum with interpreters dressed in period costume who recreate the daily routines of early Iowans. Open daily from May through October, the Living History Farms include a 1700 Ioway Indian village, 1850 pioneer farm, 1875 frontier town, 1900 horse-powered farm, and a modern crop center.

Wallace House was the home of the first Henry Wallace, a national leader in agriculture and conservation and the first editor of Wallaces' Farmer farm journal. This restored 1883 Italianate Victorian houses exhibits, artifacts, and information covering four generations of Henry Wallaces and other family members.

Historic Jordan House in West Des Moines is a stately Victorian home built in 1850 and added to in 1870 by the first white settler in West Des Moines, James C. Jordan. Completely refurbished, this mansion was part of the Underground Railroad and today houses 16 period rooms, a railroad museum, West Des Moines community history, and a museum dedicated to the Underground Railroad in Iowa. In 1893 Jordan's daughter Eda was sliding down the banister when she fell off and broke her neck. She died two days later, and her ghost is reputed to haunt the house.[60]

The Chicago Tribune wrote that Iowa's capital city has "walker-friendly downtown streets and enough outdoor sculpture, sleek buildings, storefronts and cafes to delight the most jaded stroller".[61]

Festivals and events

Des Moines plays host to a growing number of nationally acclaimed cultural events, including the annual Des Moines Arts Festival in June, Metro Arts Jazz in July,[62] Iowa State Fair in August, and the World Food & Music Festival in September.[63] On Saturdays from May through October, the Downtown Farmers' Market draws visitors from across the state. Local parades include Saint Patrick's Day Parade, Drake Relays Parade, Capitol City Pride Parade, Iowa State Fair Parade, Labor Day Parade, and Beaverdale Fall Festival Parade.

Other annual festivals and events include: Des Moines Beer Week, 80/35 Music Festival, 515 Alive Music Festival, ArtFest Midwest, Blue Ribbon Bacon Fest,[64] CelebrAsian Heritage Festival, Des Moines Pride Festival, Des Moines Renaissance Faire, Festa Italiana, Festival of Trees and Lights, World Food & Music Festival, I'll Make Me a World Iowa, Latino Heritage Festival, Oktoberfest, Winefest, ImaginEve!, Iowa's Premier Beer, Wine & Food Show, and Wild Rose Film Festival.

Museums

- Des Moines Art Center

- Jordan House Museum

- Hoyt Sherman Place

- Salisbury House

- Science Center of Iowa[65]

- State Historical Society of Iowa

- Terrace Hill – Official residence of the governor of Iowa

- Wallace House Museum

- World Food Prize Hall of Laureates

Sports

Des Moines hosts professional minor league teams in several sports — baseball, basketball, hockey, indoor football, and soccer — and is home to the sports teams of Drake University which play in NCAA Division I.

The Des Moines Menace soccer club, a member of USL League Two, play their home games at Valley Stadium in West Des Moines. Des Moines United FC of the National Premier Soccer League also utilize Valley Stadium.

Des Moines is home to the Iowa Cubs baseball team of the Triple-A East. The I-Cubs, which are the Triple-A affiliate of the major league Chicago Cubs, play their home games at Principal Park near the confluence of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers.

Wells Fargo Arena of the Iowa Events Center is home to the Iowa Barnstormers of the Indoor Football League, the Iowa Wild of the American Hockey League, and the Iowa Wolves of the NBA G League. The Barnstormers relaunched as an af2 club in 2008 before joining a relaunched Arena Football League in 2010 and the Indoor Football League in 2015; the Barnstormers had previously played in the Arena Football League from 1994 to 2000 (featuring future NFL Hall of Famer and Super Bowl MVP quarterback Kurt Warner) before relocating to New York. The Iowa Energy, a D-League team, began play in 2007. They were bought by the Minnesota Timberwolves in 2017 and were renamed the Iowa Wolves to reflect the new ownership. The Wild, the AHL affiliate of the National Hockey League's Minnesota Wild have played at Wells Fargo Arena since 2013; previously, the Iowa Chops played four seasons in Des Moines (known as the Iowa Stars for three of those seasons.)

Additionally, the Des Moines Buccaneers of the United States Hockey League play at Buccaneer Arena in suburban Urbandale.

Des Moines is also home to the Drake University Bulldogs, an NCAA Division I member of the Missouri Valley Conference, primarily playing northwest of downtown at the on-campus Drake Stadium and Knapp Center. Drake Stadium is home to the famed Drake Relays each April. In addition to the Drake Relays, Drake Stadium has hosted multiple NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships and USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships.[66]

The Vikings of Grand View University also compete in intercollegiate athletics in Des Moines. A member of the Heart of America Athletic Conference, within the NAIA, they field 21 varsity athletic teams. They were NAIA National Champions in football in 2013.

The Principal Charity Classic, a Champions Tour golf event, is held at Wakonda Club in late May or early June. The IMT Des Moines Marathon is held throughout the city each October.

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | City | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa Barnstormers | American football | Indoor Football League | Wells Fargo Arena | Des Moines | 1995 (2008) |

| Iowa Cubs | Baseball | International League, Minor League Baseball | Principal Park | Des Moines | 1969 |

| Iowa Wolves | Basketball | NBA G League | Wells Fargo Arena | Des Moines | 2007 |

| Des Moines Buccaneers | Ice hockey | United States Hockey League | Buccaneer Arena | Urbandale | 1980 |

| Iowa Wild | Ice hockey | American Hockey League | Wells Fargo Arena | Des Moines | 2013 |

| Des Moines Menace | Soccer | USL League Two | Valley Stadium | West Des Moines | 1994 |

| Des Moines United FC | Soccer | National Premier Soccer League | Valley Stadium | West Des Moines | 2021 |

| Drake Bulldogs | Multi | NCAA Division I, Missouri Valley Conference | Drake Stadium, Knapp Center | Des Moines | 1881 |

Parks and recreation

Des Moines has 76 city parks and three golf courses, as well as three family aquatic centers, five community centers and three swimming pools. The city has 45 miles (72 km) of trails. The first major park was Greenwood Park. The park commissioners purchased the land on April 21, 1894.

The Principal Riverwalk is a riverwalk park district being constructed along the banks of the Des Moines River in the downtown. Primarily funded by the Principal Financial Group, the Riverwalk is a multi-year jointly funded project also funded by the city and state. Upon completion, it will feature a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) recreational trail connecting the east and west sides of downtown via two pedestrian bridges. A landscaped promenade along the street level is planned. The Riverwalk includes the downtown Brenton Skating Plaza, open from November through March.

Gray's Lake, part of the 167 acres (68 ha) of Gray's Lake Park, features a boat rental facility, fishing pier, floating boardwalks, and a park resource center. Located just south of the downtown, the centerpiece of the park is a lighted 1.9-mile (3.1 km) Kruidenier Trail, encircling it entirely.

From downtown Des Moines primarily along the east bank of the Des Moines River, the Neil Smith and John Pat Dorrian Trails are 28.2-mile (45.4 km) paved recreational trails that connect Gray's Lake northward to the east shore of Saylorville Lake, Big Creek State Park, and the recreational trails of Ankeny including the High Trestle Trail.[67] These trails are near several recreational facilities including the Pete Crivaro Park, Principal Park, the Principal Riverwalk, the Greater Des Moines Botanical Garden, Union Park and its Heritage Carousel of Des Moines, Birdland Park and the Birdland Marina/Boatramp on the Des Moines River, Riverview Park, McHenry Park, and River Drive Park.[68] Although outside of Des Moines, Jester Park has 1,834 acres (742 ha) of land along the western shore of Saylorville Lake and can be reached from the Neil Smith Trail over the Saylorville Dam.

Just west of Gray's Lake are the 1,500 acres (607 ha) of the Des Moines Water Works Park. The Water Works Park is along the banks of the Raccoon River immediately upstream from where the Raccoon River empties into the Des Moines River. The Des Moines Water Works Facility, which obtains the city's drinking water from the Raccoon River, is entirely within the Water Works Park. A bridge in the park crosses the Raccoon River. The Water Works Park recreational trails link to downtown Des Moines by travelling past Gray's Lake and back across the Raccoon River via either along the Meredith Trail near Principal Park, or along the Martin Luther King Jr. Parkway. The Water Works Park trails connect westward to Valley Junction and the recreational trails of the western suburbs: Windsor Heights, Urbandale, Clive, and Waukee. Also originating from Water Works Park, the Great Western Trail is an 18-mile (29 km) journey southward from Des Moines to Martensdale through the Willow Creek Golf Course, Orilla, and Cumming. Often, the location for summer music festivals and concerts, Water Works Park was the overnight campground for thousands of bicyclists on Tuesday, July 23, 2013, during RAGBRAI XLI.[69]

Government

Des Moines operates under a council–manager form of government. The council consists of a mayor who is elected in citywide vote, two at-large members, and four members representing each of the city's four wards. In 2014, Jonathan Gano was appointed as the new Public Works Director.[70] In 2015, Dana Wingert was appointed as Police Chief.[71] In 2018, Steven L. Naber was appointed as the new City Engineer.[72]

The council members include:[73]

| Ward[74] | Locale | Member | Elected | Term Ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Northwest | Chris Coleman | 2023 | 2026 |

| 2 | Northeast | Linda Westergaard | 2015 | 2028 |

| 3 | Southwest | Josh Mandelbaum | 2017 | 2026 |

| 4 | Southwest | Joe Gatto | 2014 | 2028 |

| At-large | City wide | Carl Voss | 2019 | 2028 |

| At-large | City wide | Vacant | 2021 | 2026 |

| Mayor | City wide | Connie Boesen | 2023 | 2028 |

A plan to merge the governments of Des Moines and Polk County was rejected by voters during the November 2, 2004, election. The consolidated city-county government would have had a full-time mayor and a 15-member council that would have been divided among the city and its suburbs. Each suburb would still have retained its individual government but with the option to join the consolidated government at any time. Although a full merger was soundly rejected, many city and county departments and programs have been consolidated.

Education

of Drake University

The Des Moines Public Schools district is the largest community school district in Iowa with 32,062 enrolled students as of the 2012–2013 school year. The district consists of 63 schools: 38 elementary schools, eleven middle schools, five high schools (East, Hoover, Lincoln, North, and Roosevelt), and ten special schools and programs.[75] Small parts of the city are instead served by Carlisle Community Schools,[76] Johnston Community School District,[77] the Southeast Polk Community School District[78] and the Saydel School District[79] Grand View Christian School is the only private school in the city, although Des Moines Christian School (in Des Moines from 1947 to 2006) in Urbandale, Dowling Catholic High School in West Des Moines, and Ankeny Christian Academy on the north side of the metro area serve some city residents.

Des Moines is also home to the main campuses of three four-year private colleges: Drake University, Grand View University, and Mercy College of Health Sciences. The University of Iowa has a satellite facility in the city's Western Gateway Park, while Iowa State University hosts Master of Business Administration classes downtown. Simpson College, Upper Iowa University, William Penn University, and Purdue University Global. Des Moines Area Community College is the area's community college with campuses in Ankeny, Des Moines, and West Des Moines. The city is also home to Des Moines University, an osteopathic medical school.

Media

The Des Moines market, which originally consisted of Polk, Dallas, Story, and Warren counties,[80] was ranked 91st by Arbitron as of the fall of 2007 with a population of 512,000 aged 12 and older.[81] But in June 2011 it was moved up to 72nd with the addition of Boone, Clarke, Greene, Guthrie, Jasper, Lucas, Madison and Marion counties.[82]

Radio

Commercial stations

iHeartMedia owns five radio stations in the area, including WHO 1040 AM, a 50,000-watt AM news/talk station that has the highest ratings in the area[83] and once employed future President Ronald Reagan as a sportscaster. In addition to WHO, iHeartMedia owns KDRB 100.3 FM (adult hits), KKDM 107.5 FM (contemporary hits), KXNO-FM 106.3, and KXNO 1460 AM (sports radio).[84] They also own news/talk station KASI 1430 AM and hot adult contemporary station KCYZ 105.1 FM, both of which broadcast from Ames.

Cumulus Media owns five stations that broadcast from facilities in Urbandale: KBGG 1700 AM (sports), KGGO 94.9 FM (classic rock), KHKI 97.3 FM (country music), KJJY 92.5 FM (country music), and KWQW 98.3 FM (classic hip hop).[85]

Saga Communications owns nine stations in the area: KAZR 103.3 FM (rock), KAZR-HD2 (oldies), KIOA 93.3 FM (oldies), KIOA-HD2 99.9FM & 93.3 HD2 (Rhythmic Top 40), KOEZ 104.1 FM (soft adult contemporary), KPSZ 940 AM (contemporary Christian music, religious teaching, and conservative talk), KRNT 1350 AM (ESPN Radio), KSTZ 102.5 FM (adult contemporary hits), and KSTZ-HD2 (classic country).[86]

Other stations in the Des Moines area include religious stations KWKY 1150 AM, and KPUL 101.7 FM.[87]

Non-commercial stations

Non-commercial radio stations in the Des Moines area include KDPS 88.1 FM, a station operated by the Des Moines Public Schools; KWDM 88.7 FM, a station operated by Valley High School; KJMC 89.3 FM, an urban contemporary station; K213DV 90.5 FM, the contemporary Christian K-Love affiliate for the area; and KDFR 91.3 FM, operated by Family Radio. Iowa Public Radio broadcasts several stations in the Des Moines area, all of which are owned by Iowa State University and operated on campus. WOI 640 am, the networks flagship station, and WOI-FM 90.1, the networks flagship "Studio One" station, are both based out of Ames and serve as the area's National Public Radio outlets. The network also operates classical stations KICG, KICJ, KICL and KICP.[88] The University of Northwestern – St. Paul operates Contemporary Christian simulcasts of KNWI-FM at 107.1 Osceola/Des Moines, KNWM-FM at 96.1 Madrid/Ames/Des Moines, and K264CD at 100.7 in downtown Des Moines. Low-power FM stations include KFMG-LP 99.1, a community radio station broadcasting from the Hotel Fort Des Moines and also webstreamed.[87][89]

Television

The Des Moines-Ames media market consists of 35 central Iowa counties: Adair, Adams, Appanoose, Audubon, Boone, Calhoun, Carroll, Clarke, Dallas, Decatur, Franklin, Greene, Guthrie, Hamilton, Hardin, Humboldt, Jasper, Kossuth, Lucas, Madison, Mahaska, Marion, Marshall, Monroe, Pocahontas, Polk, Poweshiek, Ringgold, Story, Taylor, Union, Warren, Wayne, Webster, and Wright.[80] It was ranked 71st by Nielsen Media Research for the 2008–2009 television season with 432,410 television households.[90]

Commercial television stations serving Des Moines include CBS affiliate KCCI channel 8, NBC affiliate WHO-DT channel 13, and Fox affiliate KDSM-TV channel 17. ABC affiliate WOI-TV channel 5 and CW affiliate KCWI-TV channel 23 are both licensed to Ames and broadcast from studios in West Des Moines. KFPX-TV channel 39, the local ION affiliate, is licensed to Newton. Two non-commercial stations are also licensed to Des Moines: KDIN channel 11, the local PBS member station and flagship of the Iowa Public Television network, and KDMI channel 19, a TCT affiliate. Mediacom is the Des Moines area's cable television provider. Television sports listings for Des Moines and Iowa can be found on the Des Moines Register website.[91]

The Des Moines Register is the city's primary daily newspaper. As of March 31, 2007, the Register ranked 71st in circulation among daily newspapers in the United States according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations with 146,050 daily and 233,229 Sunday subscribers.[92] Weekly newspapers include Juice, a publication aimed at the 25–34 demographic published by the Register on Wednesdays; Cityview, an alternative weekly published on Thursdays; and the Des Moines Business Record, a business journal published on Sundays, along with the West Des Moines Register, the Johnston Register, and the Waukee Register on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, or Thursdays depending on the address of the subscriber. Additionally, magazine publisher Meredith Corporation was based in Des Moines prior to its acquisition by IAC and merger with Dotdash in 2021.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Des Moines has an extensive skywalk system within its downtown core. With over four miles of enclosed walkway, it is one of the largest of such systems in the United States. The Des Moines Skywalk System has been criticized for hurting street-level business, though a recent initiative has been made to make street-level Skywalk entrances more visible.

Interstate 235 (I-235) cuts through the city, and I-35 and I-80 both pass through the Des Moines metropolitan area, as well as the city of Des Moines. On the northern side of the city of Des Moines and passing through the cities of Altoona, Clive, Johnston, Urbandale and West Des Moines, I-35 and I-80 converge into a long concurrency while I-235 takes a direct route through Des Moines, Windsor Heights, and West Des Moines before meeting up with I-35 and I-80 on the western edge of the metro. The Des Moines Bypass passes south and east of the city.[93] Other routes in and around the city include US 6, US 69, Iowa 28, Iowa 141, Iowa 163, Iowa 330, Iowa 415, and Iowa 160.

Des Moines's public transit system, operated by DART (Des Moines Area Regional Transit), which was the Des Moines Metropolitan Transit Authority until October 2006, consists entirely of buses, including regular in-city routes and express and commuter buses to outlying suburban areas.

Characteristics of household ownership of cars in Des Moines are similar to national averages. In 2015, 8.5 percent of Des Moines households lacked a car, and increased to 9.6 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Des Moines averaged 1.71 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[94]

Burlington Trailways, and Jefferson Lines run long-distance, intercity bus routes through Des Moines. The bus station is located north of downtown.

Although Des Moines was historically a train hub, it does not have direct passenger train service. For east–west traffic it was served at the Rock Island Depot by the Corn Belt Rocket express from Omaha to the west, to Chicago in the east. The Rock Island also offered the Rocky Mountain Rocket from Colorado Springs in the west, to Chicago, and the Twin Star Rocket to Minneapolis to the north and Dallas and Houston to the south. The last train was an unnamed service ending at Council Bluffs, and it was discontinued on May 31, 1970.[95][96] Today, this line constitutes the mainline of the Iowa Interstate Railroad.

Other railroads used the East Des Moines Union Station. Northward and northwest bound, there were Chicago and North Western trains to destinations including Minneapolis. The Wabash Railroad ran service to the southeast to St. Louis. These lines remain in use but are now operated by Union Pacific and BNSF.

The nearest Amtrak station is in Osceola, about 40 miles (64 km) south of Des Moines. The Osceola station is served by the Chicago–San Francisco California Zephyr; there is no Osceola–Des Moines Amtrak Thruway connecting service.[97] There have been proposals to extend Amtrak's planned Chicago–Moline Quad City Rocket to Des Moines via the Iowa Interstate Railroad.[98][99]

The Des Moines International Airport (DSM), on Fleur Drive in the southern part of Des Moines, offers nonstop service to destinations within the United States. The only international service is cargo service, but there have been discussions about adding an international terminal.

Sister cities

The Greater Des Moines Sister City Commission, with members from the City of Des Moines and the suburbs of Cumming, Norwalk, Windsor Heights, Johnston, Urbandale, and Ankeny, maintains sister city relationships with:[100]

Kōfu, Japan (1958)

Kōfu, Japan (1958) Saint-Étienne, France (1985)

Saint-Étienne, France (1985) Shijiazhuang, China (1985)

Shijiazhuang, China (1985) Stavropol, Russia (1992) (suspended)[101]

Stavropol, Russia (1992) (suspended)[101] Pristina, Kosovo (2018) (Kosovo also opened Consulate in downtown Des Moines in 2015 – List of diplomatic missions of Kosovo)[102]

Pristina, Kosovo (2018) (Kosovo also opened Consulate in downtown Des Moines in 2015 – List of diplomatic missions of Kosovo)[102] Catanzaro, Italy (2006)

Catanzaro, Italy (2006) Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia (1987)[103]

Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia (1987)[103]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ↑ Official records for Des Moines kept August 1878 to August 1939 at downtown and at Des Moines Int'l since September 1939. For more information, see Threadex

- 1 2 From 15% sample

- ↑ The total for each race includes those who reported that race alone or in combination with other races. People who reported a combination of multiple races may be counted multiple times, so the sum of all percentages will exceed 100%.

- ↑ Hispanic and Latino origins are separate from race in the U.S. Census. The Census does not distinguish between Latino origins alone or in combination. This row counts Hispanics and Latinos of any race.

References

- ↑ Shankle, George Earlie (1955). American nicknames; their origin and significance. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company. pp. 123. ISBN 978-0-82420-004-6.

Des Moines was nicknamed the Hartford of the West because like Hartford, Conn., it is an insurance center.

- ↑ Neal R. Peirce (1973), The Great Plains States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Nine Great Plains States Archived May 1, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05349-0, page 106

- ↑ "City Manager's Office". City of Des Moines – City Manager's Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ↑ City of Des Moines. "City of Des Moines Action Center: City History". Archived from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved December 20, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "2020 Census State Redistricting Data". census.gov. United states Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2010-2018". Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Microsoft behind nearly $700 million data center investment in West Des Moines". Des Moines Register. June 21, 2013. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Facebook to build data center near Des Moines, Iowa". Reuters. April 23, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ Nagourney, Adam (December 2, 2007). "In the Spotlight, Ready for Its Close-Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Defining 'Des Moines'. Archived July 23, 2012, at archive.today". Des Moines Register. September 14, 2003.

- ↑ Modified from Newsletter of the Iowa Archeological Society 58(1):8

- ↑ Heldt, Diane (August 18, 2011). "UI archaeologists find 7,000-year-old site in Des Moines: More than 6,000 artifacts were found". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ↑ Schoen, Christopher M. (2005). "A Point of Land and Prehistoric Peoples". Iowa Heritage Illustrated. 86 (1): 8–9. doi:10.17077/1088-5943.1178.

- 1 2 Whittaker, William E. (2008). "Prehistoric and Historic Indians in Downtown Des Moines". Newsletter of the Iowa Archeological Society. 58 (1): 8–10.

- 1 2 3 Schoen, Christopher M.; W.E. Whittaker; K.E.M. Gourley (2009). "Fort Des Moines No. 2, 1843–1846". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 161–177. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ↑ Mather, David and Ginalie Swaim (2005) "The Heart of the Best Part: Fort Des Moines No. 2 and the Archaeology of a City", Iowa Heritage Illustrated 86(1):12–21.

- ↑ James H. Lees, "History of Coal Mining in Iowa", Chapter III of Annual Report, 1908. Archived January 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Iowa Geological Survey. 1909. p. 566.

- ↑ Perkins, Arozina, 1851 letter in: (1984) "Teaching in Fort Des Moines, Iowa: November 13, 1850 to March 21, 1851." In Women Teachers on the Frontier, edited by P. W. Kaufman, pp. 126–143. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

- ↑ Mills and Company (1866) Des Moines City Directory and Business Guide. Des Moines, Iowa: Mills and Company, p. 6. Microfilm, State Historical Society Library, Iowa City.

- ↑ Brigham, Johnson (1911) Des Moines: The Pioneer of Municipal Progress and Reform of the Middle West. Volume 1. Chicago: S. J. Clarke

- ↑ James H. Lees, "History of Coal Mining in Iowa", Chapter III of Annual Report, 1908 Archived January 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Iowa Geological Survey, 1909, pages 566–569.

- ↑ Henry Hinds, "The Coal Deposits of Iowa", Annual Report, 1908 Archived January 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Iowa Geological Survey, 1909, pages 121–127, and see map on page 102.

- ↑ Tally Sheet, Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Convention of the United Mine Workers of America Archived January 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Jan 16 – February 2, 1912, Indianapolis; Volume 2, pages 180A–184A.

- 1 2 3 4 "Iowa — Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Historic American Buildings Survey Records". Hdl.loc.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ Dahl, Orin L. (1978) Des Moines: Capital City: A Pictorial and Entertaining Commentary on the Growth and Development of Des Moines, Iowa. Continental Heritage, Tulsa.

- ↑ Gardiner, Allen (2004) Des Moines: A History in Pictures. Heritage Media, San Marcos, California.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Iowa: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (XLS) on June 28, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Flood-Ravaged Iowa Scrambles to Mend Levees, Protect Water Supplies and Salvage Homes". Fox News Channel. June 14, 2008. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ↑ "The Tomorrow Plan". Des Moines Area MPO. December 22, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Gazetteer files, 2015". Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files 2015". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- 1 2 City of Des Moines. "Annexation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Greater Des Moines Convention and Visitors Bureau Archived June 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Seedesmoines.com (July 21, 1998). Retrieved on September 5, 2013.

- ↑ Archived May 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: Des Moines INTP AP, IA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for DES MOINES/MUNICIPAL, IA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Des Moines, Iowa, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 "Des Moines (city), Iowa". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Hispanic or Latino or Not Hispanic or Latino By Race: Des Moines city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ↑ "2020 Decennial Census: Des Moines city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Group Quarters Population, 2020 Census: Des Moines city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Selected Economic Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Des Moines city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Selected Social Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Des Moines city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "The Sudan Project: Being Sudanese American in Iowa". www.thegazette.com.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Major Employers in the Greater Des Moines Region" (PDF).

- ↑ "Iowa Economic Development". November 9, 2021.

- ↑ Neal R. Peirce (1973), The Great Plains States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Nine Great Plains States, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05349-0, page 106

- ↑ "The Insurance Capital of the U.S.? Look to Des Moines". www.uschamber.com/co. September 27, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ↑ "Principal Financial". Fortune. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ↑ Greater Des Moines Partnership. "Large Private and Publicly Held Employers, Greater Des Moines" (PDF). Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Can Kemin help revive Des Moines' floundering agribusiness park?". Des Moines Register. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Metro Arts Alliance of Greater Des Moines". Metroarts.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ Jordan House | Haunted Places | West Des Moines, Iowa Archived December 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Haunted Places (August 13, 2013). Retrieved on September 5, 2013.

- ↑ chigagotribune.com. "Des Moines, Iowa". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Jazz in July — Metro Arts Alliance". Jazzinjuly.org. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ "World Food & Music Festival". Worldfoodandmusicfestival.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Blue Ribbon Bacon Festival". Blueribbonbaconfestival.gov. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Science Center of Iowa". Sciowa.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ Drake University (press release) (December 13, 2007). "Drake Awarded 2010 USA Outdoor Track & Field Championships". Archived from the original on September 3, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Neil Smith and John Pat Dorrain Trails". Iowa Trails. Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Parks and Recreation". City of Des Moines. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Water Works Park". Des Moines Water Works. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ↑ Meinch, Timothy (December 31, 2014). "Des Moines names new public works director". The Des Moines Register. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ Magel, Todd (February 9, 2015). "New Des Moines police chief approved 7-0". KCCI. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ↑ "City of Des Moines Selects Steve Naber as City Engineer" (PDF). Dmgov.org. April 13, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Government of the City of Des Moines". City of Des Moines. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ↑ "Government of the City of Des Moines". www.dsm.city. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ↑ Des Moines Public Schools. "School Facts, Facts and Figures". Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Our Location." (Archive) Carlisle Community Schools. Retrieved on April 3, 2013. "Carlisle Elementary School, which is immediately adjacent to the high school and the district office, serves students from pre-kindergarten to grade 3."

- ↑ Johnston High School

- ↑ "Southeast Polk Community School District". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "District Information". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013.

- 1 2 Arbitron. "Arbitron Radio Metros Based on Fall 2006 Market Definitions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Arbitron. "Market Ranks and Schedule (51–100)". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Arbitron Redefines Diary Metro Surveys" Archived July 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine from All Access (June 27, 2011)

- ↑ Arbitron. "Arbitron Ratings Data". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Clear Channel Communications. "Clear Channel Radio: Station Search". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Citadel Communications. "Station and Market Finder". Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Saga Communications (August 18, 2022). "Des Moines, IA". Des Moines Radio Group. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- 1 2 Northpine.com. "Des Moines Dial Guides". Archived from the original on January 22, 2000. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Iowa Broadcasters' Association. "Iowa Non-Commercial/Educational Radio Stations". Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ KFMG 99.1 Archived January 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. KFMG 99.1. Retrieved on September 5, 2013.

- ↑ Nielsen Media Research. "Nielsen Local Television Market Universe Estimates". Archived from the original (XLS) on April 1, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Sports TV listings for Des Moines and Iowa". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. April 22, 2018. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ↑ BurrellesLuce. "Top 100 US Daily Newspapers" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ "New Interstate 335 Coming to DM Area?". KCCI News Channel 8. May 9, 2011. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Rock Island Lines, Table 1". Official Guide of the Railways. National Railway Publication Company. 102 (12). May 1970.

- ↑ Paul C. Nelson, University of Iowa, 'Annals of Iowa,' c. 1971, 'a"Rise and Decline of the Rock Island Passenger Train in the 20th Century,'a" Part II, p. 751 https://pubs.lib.uiowa.edu/annals-of-iowa/article/6748/galley/115521/view/

- ↑ "The Amtrak System" (PDF). Amtrak (Map). March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017. While this source is suggestive, it is not definitive: the map does not include all stations, due to the zoom (c.f. the tiny print).

- ↑ "Iowa DOT Chicago-Iowa City Executive Summary.pdf" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2017.

- ↑ Iowa State Rail Plan Final (PDF). Iowa DOT. 2017. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Greater Des Moines Sister Cities Commission". City of Des Moines. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ↑ "Des Moines Suspends Sister City Relationship with Stavropol, Russia". City of Des Moines, Iowa. March 10, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ↑ Aschbrenner, Joel (November 3, 2015). "Kosovo to open consulate in downtown Des Moines". Des Moines register. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Who We Are". Iowa Sister States. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

Bibliography

- Friedericks, William B. Covering Iowa: The History of the Des Moines Register and Tribune Company, 1849-1985 (Iowa State University Press, 2000), 318 pp.

- "City of Des Moines Action Center Historical Guide". Archived from the original on December 7, 2006.

- Henning, Barbara Beving Long & Beam, Patrice K. (2003). Des Moines and Polk County: Flag on the Prairie. Sun Valley, California: American Historical Press. ISBN 1-892724-34-0.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)