Colony of Maryland in Africa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1834–1857 | |||||||

Flag (1854–57) | |||||||

Map of modern-day Maryland County in Liberia | |||||||

| Status | Private Colony of the Maryland State Colonization Society (1834–54) Republic (1854–57) | ||||||

| Capital | Harper | ||||||

| Common languages | English (de facto) Grebo | ||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||

| Government | Private Colony of the Maryland State Colonization Society (1834–54) Republican Government(1854–57) | ||||||

| Governor | |||||||

• 1836–51 | John Brown Russwurm | ||||||

• 1854 | Samuel Ford McGill | ||||||

• 1854–56 | William A. Prout | ||||||

• 1856–57 | Boston Jenkins Drayton | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Establishment as colony | February 12 1834 | ||||||

| January 31, 1853 | |||||||

• Declaration of independence | May 29, 1854 | ||||||

• Annexed by Liberia | March 18 1857 | ||||||

| Currency | United States dollar | ||||||

| |||||||

The Republic of Maryland (also known variously as the Independent State of Maryland, Maryland-in-Africa, and Maryland in Liberia) was a country in West Africa that existed from 1834 to 1857, when it was merged into what is now Liberia. The area was first settled in 1834 by freed African-American slaves and freeborn African Americans primarily from the U.S. state of Maryland, under the auspices of the Maryland State Colonization Society.[1][2]

The larger American Colonization Society was founded in 1816. It supported the settlement of thousands of free people of color to its colony of Liberia, in West Africa. There were also initially separate settlements founded by state colonization societies of Mississippi (Mississippi-in-Africa), Kentucky (Kentucky in Africa), Georgia,[3] Pennsylvania,[4] and Louisiana. A New Jersey colony was planned.[5]

In 1838, these African-American settlements were united into the Commonwealth of Liberia, which declared independence from the American Colonization Society on July 26, 1847. The Maryland colony remained separate from the Commonwealth of Liberia, as the colonization society wished to maintain its trade monopoly in the area. On February 2, 1841, Maryland-in-Africa became the Independent State of Maryland. Following an independence referendum in 1853, the state declared its independence on May 29, 1854, under the name Maryland in Liberia,[6] with its capital at Harper.

History

The American Colonization Society was founded in 1816, in part due to alarms over the violence of the Haitian slave revolution and its aftermath, which resulted in independence for that country in 1804. Fears were raised about the effects of emancipation of slaves in the United States.[7]

In this period, both slaveholders and abolitionists collaborated on the project to transport free blacks to Africa, though for different reasons. They suggested it was "repatriation", but by this time most African Americans were native-born in the United States, and said they were no more African than the Americans are British. Slaveholders believed that free blacks threatened the stability of their slave societies. Nat Turner's rebellion of 1831 panicked Southerners, who feared another slave uprising and seizure of the country, as had recently happened in Haiti. Abolitionists, many of them ministers, hoped to persuade slaveholders through their religion to manumit (free) their slaves and also worried about the discrimination faced by free blacks in the United States.

Those who supported relocation to West Africa believed (or said they believed) that the African Americans would create there better polities; first as some vague type of colonies, then countries, away from white prejudice, discrimination, and economic exploitation. While thousands of free blacks did relocate to the colonies, most free African Americans opposed this project, claiming the right of their birth in the United States and wanting to improve their lives there.[8]

The U.S. state of Maryland had an increasing proportion of free blacks among its African-American population. During the first two decades after the American Revolution, about 25% of blacks were freed, in part because slaveholders were inspired by the war's ideals. Practically, changing labor needs meant that fewer slaves were required.[9] By 1810 some 30% of northern Maryland's blacks were free, in what was a more urbanized region, but so were 20% of blacks in the southern part of the state.[9]: 291 In the next two decades the number of free blacks increased markedly in the northern part of the state, and many congregated in Baltimore, the state's and the South's largest city.[9] By 1830 Maryland had a total of 52,938 free blacks: 51.3% of blacks in northern Maryland were free, and the black population of Baltimore was 75% free. In southern Maryland, free blacks made up 24.7% of the black population.[9]

The Maryland State Colonization Society was originally a branch of the American Colonization Society, which had founded the colony of Liberia at Monrovia on January 7, 1822. The Maryland Society decided to establish a new settlement of its own to accommodate its emigrants and with the intention of controlling trade to its colony. In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature in the United States appropriated US$10,000 for 26 years to transport 10,000 free blacks and ex-slaves, and 400 Caribbean slaves from the United States and the Caribbean islands, respectively, to Africa. It founded the Maryland State Colonization Society for this purpose.[10] Nowhere near that number were actually transported.

Settlement of Cape Palmas

The first area in the future Republic of Maryland to be settled by the Maryland Colonization Society was Cape Palmas, in 1834, somewhat south of the rest of the American colony.[1] The Cape is a small, rocky peninsula connected to the mainland by a sandy isthmus. Immediately to the west of the peninsula is the estuary of the Hoffman River. Approximately 21 km (15 mi) along the coast to the east, the Cavalla River empties into the sea, marking the border between Liberia and the Ivory Coast. It marks the western limit of the Gulf of Guinea, according to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO).

Most of the settlers were freed African-American slaves and freeborn African Americans primarily from the state of Maryland.[11] The Colonization Society organizers thought they could establish new trading ties by relocating African Americans to West Africa. The colony was named Maryland in Africa (also known as Maryland in Liberia) on February 12, 1834.

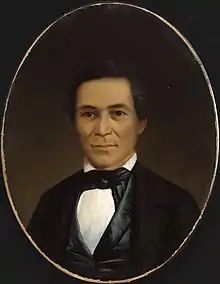

John Brown Russwurm

In 1836 the Colonization Society appointed its first mixed-race governor, John Brown Russwurm (1799–1851), who served as governor for more than a dozen years, until his death. Russwurm encouraged the immigration of African Americans to Maryland in Africa, and supported agriculture and trade.[12] He had begun his career working as the colonial secretary for the American Colonization Society between 1830 and 1834. He also worked as the editor of the Liberia Herald. He resigned this post in 1835 to protest America's colonization policies.

In 1838, a number of other American settlements on the west coast of Africa united to form the Commonwealth of Liberia, which declared its independence on July 26, 1847.

Two American visitors in 1851 reported the population of "Maryland in Liberia" to be between 900 and 1,000, with four churches and six schools.[13]

The colony of Maryland in Liberia remained independent, as the Maryland State Colonization Society wished to maintain its trade monopoly in the area. On February 2, 1841, Maryland-in-Africa declared its statehood and became the State of Maryland. In 1847 the Maryland State Colonization Society published the Constitution and Laws of Maryland in Liberia, based on the United States Constitution.

Declaration of Independence, and annexation by Liberia

On May 29, 1854, the State of Maryland declared its independence, naming itself Maryland in Liberia,[6] with its capital at Harper. It was also known as the Republic of Maryland. It held the land along the coast between the Grand Cess and San Pedro rivers. It lasted three years as an independent state.

Soon afterward, local tribes, including the Grebo and the Kru, attacked the State of Maryland. Unable to maintain its own defense, Maryland appealed for help to Liberia, its more powerful neighbor. President Roberts sent military assistance, and an alliance of Marylanders and Liberian militia troops successfully repelled the local tribesmen. The Republic of Maryland recognized that it could not survive as an independent state, and following a referendum, Maryland was annexed by Liberia on April 6, 1857, becoming known as Maryland County.

Legacy

A statue of John Brown Russwurm was erected near his burial site at Harper, Cape Palmas, Liberia.[14]

Governors of Maryland-in-Africa

(Dates in italics indicate de facto continuation of office)

| Term | Incumbent |

|---|---|

| February 12, 1834 – February 1836 | James Hall, Governor, Maryland in Africa |

| February 1836 – July 1, 1836 | Oliver Holmes Jr., Governor, Maryland in Africa |

| July 1, 1836 – September 28, 1836 | Three-member Committee, Maryland in Africa |

| September 28, 1836 – February 2, 1841 | John Brown Russwurm, Governor, Maryland in Africa |

| February 2, 1841 – June 9, 1851 | John Brown Russwurm, Governor, State of Maryland in Liberia |

| June 9, 1851 – 1852 | Samuel Ford McGill, acting Governor, State of Maryland in Liberia |

| 1852 – May 29, 1854 | Samuel Ford McGill, Governor, State of Maryland in Liberia |

| May 29, 1854 – June 8, 1854 | Samuel Ford McGill, Governor, The Independent State of Maryland in Liberia |

| June 8, 1854 – April 1856 | William A. Prout, Governor, The Independent State of Maryland in Liberia |

| April 1856 – March 18, 1857 | Boston Jenkins Drayton, Governor, The Independent State of Maryland in Liberia |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 The African Repository, Volume 14, p.42 Retrieved March 13, 2010

- ↑ Hall, Richard, On Afric's Shore: A History of Maryland in Liberia, 1834-1857

- ↑ "[Freed American Slave Colony] (Maryland In Liberia)". www.raremaps.com. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Merchant Congressman in the Young Republic: Samuel Smith of Maryland 1752-1839". The SHAFR Guide Online. doi:10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim030060173. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Arrival, and Intelligence from Liberia". African Repository. Vol. 32, no. 8. August 1856. p. 229.

- 1 2 Constitution and Laws of Maryland in Liberia, p.1 Retrieved March 13, 2010

- ↑ Geggus, David (2017), Eltis, David; Richardson, David; Drescher, Seymour; Engerman, Stanley L. (eds.), "Slavery and the Haitian Revolution", The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 4: AD 1804–AD 2016, The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 4, pp. 321–343, ISBN 978-0-521-84069-9, retrieved June 15, 2022

- ↑ Franklin, Vincent P. (1974). "Education for Colonization: Attempts to Educate Free Blacks in the United States for Emigration to Africa, 1823-1833". The Journal of Negro Education. 43 (1): 99–100. doi:10.2307/2966946. JSTOR 2966946.

- 1 2 3 4 Freehling, William H. (1991). The Road to Disunion, Volume 1: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976276-7.

- ↑ Latrobe, John H. B. (1885). Maryland in Liberia: a History of the Colony Planted By the Maryland State Colonization Society Under the Auspices of the State of Maryland, U. S. At Cape Palmas on the South-West Coast of Africa, 1833-1853. Maryland Historical Society. p. 125. ISBN 9780404576219.

- ↑ Hall, Richard (2003). On Afric's Shore: A History of Maryland in Liberia, 1834-1857. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society.

- ↑ Lear, Alex (December 7, 2006). "Crossing the color line". The Community Leader. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Fuller Jr, Thomas; Janifer, Benjamin (1852) [December 17, 1851], "Mressrs. Fuller and Janifer's Report", Thirty-fifth annual report of the American Colonization Society : with the proceedings of the Board of Directors and of the Society, and the addresses delivered at the annual meeting, January 20, 1852 : to which is added an appendix, containing information about going to Liberia; things which every emigrant ought to know; Messrs. Fuller and Janifer's report, and a table of emigrants, Washington, D.C.: American Colonization Society, pp. 44–48, at p. 46

- ↑ The World Book encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book. 1996. ISBN 0-7166-0096-X. Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2010