Baku is the capital of Azerbaijan Republic, which was also the capital of Shirvan (during the reigns of Akhsitan I and Khalilullah I), Baku Khanate, Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and Azerbaijan SSR and the administrative center of Russian Baku governorate. Baku is derived from the old Persian Bagavan, which translates to "City of God".[1] A folk etymology explains the name Baku as derived from the Persian Bādkube (بادکوبه ), meaning "city where the wind blows", due to frequent winds blowing in Baku. However, the word Bādkube was invented only in the 16th or 17th century, whereas Baku was founded at least before the 5th century AD.[2]

Names in mediaeval sources

| Centuries/Years | Sources | Name of Baku |

|---|---|---|

| 5th–8th century AD | Movses Khorenatsi | Atli-Bagavan

Ateshi-Bagavan or simply Bagavan |

| 930 AD | Istakhri | Bakuh |

| 943–944 AD | Al-Masudi | Bakuh |

| 942–952 AD | Abu Dulaf | Bakuya |

| 982 AD | Hudud al-'Alam | Baku |

| 985 AD | Al-Muqaddasi | Bakuh |

| 12th century | Khaqani | Baku |

| 13th century | Yaqut al-Hamawi | Bakuya |

| 14th century | Rashidaddin | Baku |

| 15th century | Abdurrashid Bakuvi | Bakuya |

| 16th century | Hasan bey Rumlu | Baku |

| 17th century | Evliya Chalabi | Baku |

Starting from the 13th century AD the name of Baku begins to appear in mediaeval European Sources. Spelling of the name varies from Vahcüh (Pietro Della Valle), to Bakhow, Baca, Bakuie and Backu.

On the coins minted by Shirvanshahs name appears as Bakuya.

Other explanations

Various different hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etymology of the word Baku. According to L.G.Lopatinski[3] and Ali Huseynzade[4] "Baku" is derived from Turkic word for "hill". K.P. Patkanov, a specialist in Caucasian history, also explains the name as "hill" but in Lak language.[4]

Prehistoric and ancient history

Around 1000 years ago, the territory of modern Baku and Absheron was savanna with rich flora and fauna. Traces of human settlement go back to the Stone Age. From the Bronze Age there have been rock carvings discovered near Bayil, and a bronze figure of a small fish discovered in the territory of the Old City. This have led some to suggest the existence of a Bronze Age settlement within the city's territory.[5] Near Nardaran in a place called Umid Gaya, a prehistoric observatory was discovered, where on the rock the images of sun and various constellations are carved together with a primitive astronomic table.[6] Further archeological excavations revealed various prehistoric settlements, native temples, statues and other artifacts within the territory of the modern city and around it.[7]

In the 1st century, Romans organized two Caucasian campaigns and reached Baku. Near Baku, in Gobustan, Roman inscriptions dating from 84–96 AD were discovered. The remnant of this period is the village of Ramana in the Sabunchu district of Baku.

In the Life of the Apostle Bartholomew, Baku is identified as Armenian albanus.[8] Some historians assume that during the existence of Caucasian Albania Baku was called Albanopolis.[9] Local church traditions record the belief that Bartholomew's martyrdom occurred at the bottom of the Maiden Tower within the Old City, where according to historical data, a Christian church was built on the site of the pagan temple of Arta.

A record from the 5th-century historian Priscus of Panium was the first to mention the famous Bakuvian fires (ex petra maritima flamma ardet – from the maritime stone flame emerges). Owing to these eternal fires Baku became a major center of ancient Zoroastrianism. Sassanid shah Ardashir I gave orders "to keep an inextinguishable fire of the god Ormazd" in the city temples.[10]

Medieval and early modern period

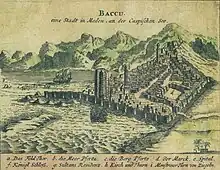

There is little or no information regarding Baku in medieval sources until the 10th century.[11] The earliest numismatic evidence found in the city is an Abbasid coin dating from the 8th century AD. At that time Baku was a domain of the Arab Caliphate and later of Shirvanshahs. During this period, they frequently came under assault of the Khazars and (starting from the 10th century) the Rus. Shirvanshah Akhsitan I built a navy in Baku and successfully repelled another Rus assault in 1170. After a devastating earthquake struck Shamakhy, the capital of Shirvan, Shirvanshah's court moved to Baku in 1191. A mint was put into operation.[12]

Between the 12th and 14th centuries, a massive fortification was undertaken in the city and around it. The Maiden Tower, castles of Ramana, Nardaran, Shagan and Mardakan, and also famous Sabayel castle on the island of the Baku bay was built during this period. The city walls were also rebuilt and strengthened.

The biggest problem of Baku during this time was the transgression of the Caspian Sea. The rising levels of the water from time to time engulfed much of the city and the famous castle of Sabayel went completely into the sea in the 14th century. These led to several legends about submerged cities such as Shahriyunan ("Greek city").

Hulagu Khan occupied Baku under the domain of the Shirvan state during the third Mongol campaign in Azerbaijan (1231–1239) and it became a winter residence for Ilkhanids. In the 14th century, the city prospered under Muhammad Oljeitu who relieved it from some of the heavy taxes. Bakuvian poet Nasir Bakui wrote a panegyric to Oljeitu thus creating the first piece of poetry in Azerbaijani language.

Marco Polo had written of Baku oil exports to Near Eastern countries.[13] The city also traded with the Golden Horde, the Moscow Princedom, and European countries.

In 1501, Safavid shah Ismail I laid siege to Baku. The besieged inhabitants resisted, relying for defense on their fortifications. Due to the resistance, Ismail ordered part of the fortification's wall to be undermined. The fortress's defense was destroyed and many inhabitants were slaughtered. In 1538, the Safavid Shah Tahmasp I put an end to the Shirvanshahs' reign and in 1540, Baku was recaptured by Safavid troops again.

Between 1568 and 1574 there is a record of six English missions to Baku. English men named Thomas Bannister and Jeffrey Duckett described Baku in their correspondence. They wrote that the "...town is a strange thing to behold, for there issueth out of the ground a marvelous quantity of oil, which serveth all the country to burn in their houses. This oil is black and is called nefte. There is also by the town of Baku, another kind of oil which is white and very precious, and it is called petroleum."[14] The first oil well outside of Baku was drilled in 1594 by a craftsman named A. Mamednur oglu. This man finished the construction of a high-efficiency oil well in the Balakhany settlement.[15] This area was historically outside city territory.

In 1636, German diplomat and traveler Adam Olearius described Baku's 30 oil fields, noting that there was a great quantity of brown oil. In 1647, famous Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi visited Baku. In April 1660, Cossacks under Stepan Razin attacked the Baku coast and plundered the village of Mashtaga. In 1683, Baku was visited by the ambassador of the Kingdom of Sweden, Engelbert Kaempfer. In the following year, Baku was temporarily recaptured by the Ottoman Empire.

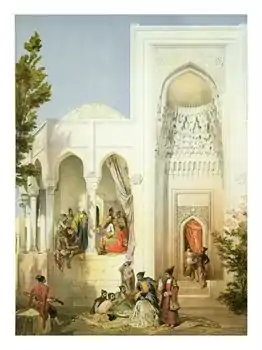

Baku is noted for being a focal point for traders from all across the world during the Early modern period, commerce was active and the area was prosperous. Notably, traders from the Indian subcontinent established themselves in the region. These Indian traders built the Ateshgah of Baku during 17th–18th centuries; the temple was used as a Hindu, Sikh, and Parsi place of worship.[16]

Fall of Safavids and Baku Khanate

The fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1722 caused widespread chaos. Baku was invaded by the Russian and Ottoman empires.

On 26 June 1723, after a long siege, Baku surrendered to the Russians and the Safavids were forced to cede the city alongside many other of their Caucasian territories. In accordance with Peter the Great's decree, the soldiers of two regiments (2,382 people) were left in the Baku garrison under the command of Prince Baryatyanski, the commandant of the city. Peter the Great, while equipping a new military expedition commanded by General Mikhail Matyushkin, charged him with sending more oil from Baku to St. Petersburg, "which is a basis of an eternal and sacred flame"—Old Russian: "коя является основой вечного и священного пламени". However, due to Peter's death, this order was not carried out.

In 1733, Baku was visited by physician Ioann Lerkh, an employee of the Russian embassy and, like many others before him, described the city oil fields. By 1730, the situation had deteriorated for the Russians as Nadir Shah's successes in Shirvan forced the Russians to make an agreement near Ganja on 10 March 1735, ceding the city and all other conquered territories in the Caucasus back to Persia.

After the disintegration of the Safavid Empire and after the death of Nader Shah, the semi-independent principality of Baku Khanate was formed in 1747 following the power vacuum which had been created. It was ruled by Mirza Muhammed Khan and soon became a dependency of the much stronger Quba Khanate. The population of Baku was small (approximately 5,000), and the economy was ruined as a result of constant warfare, banditry, and inflation. The khans benefited, however, from the sea trade with the rest of Iran. Feudal infighting in the 1790s resulted in the dominance of an anti-Russian faction in the city resulting in the Russian-leaning brother of the Khan being exiled to Quba.

By the end of the 18th century, Tsarist Russia now began a more firm policy with the intent to conquer all of the Caucasus at the expense of Persia and Ottoman Turkey. In the spring of 1796, by Yekaterina II's order, General Valerian Zubov's troops started a large campaign against Qajar Persia following the sack of Tbilisi and Persia's aim to restore its suzerainty over Georgia and Dagestan. Zubov had sent 13,000 men to capture Baku, and it was overrun subsequently without any resistance. On 13 June 1796, a Russian flotilla entered Baku Bay, and a garrison of Russian troops was placed inside the city. Later, however, Pavel I ordered the cessation of the campaign and the withdrawal of Russian forces following the death of his predecessor, Yekatarina II. In March 1797, the tsarist troops left Baku.

Persia's forced ceding to the Russian Empire

Tsar Alexander I set out to conquer Baku once again during the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) during which Pavel Tsitsianov tried to capture Baku in January 1806. But aide-de-camp and cousin of Huseyngulu Khan suddenly shot Tsitsianov to death during the presentation of the city's keys to him. Left without a commander, the Russian Army left Baku and the occupation of Baku Khanate was delayed for a year. Baku was captured on October of the same year and eventually absorbed into the Russian Empire after formal ceding of the city amongst other integral territories in the North Caucasus and South Caucasus by Persia in the Treaty of Gulistan, in 1813. However, it was not until the aftermath of the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay that Baku came under nominal Russian rule, as the city was retaken by Persia during the war.[17]

When Baku was occupied by the Russian troops during the war of 1804–1813, nearly the entire population of some 8,000 people was ethnic Tat.[18]

Early period

In 1809, at the time of the Russian conquest, the Muslim population grew to become 95% of the city's population.

On 10 July 1840, the Russian Duma approved "The Principles of Ruling of the Transcaucasian Region", and Baku uyezd was turned into an administrative region of the Russian Empire.

Fortstadt, a new suburb, grew from the dispersed buildings scattered within the city's fortifications. Medieval seaside fortifications were demolished in 1861 to allow for the creation of the port and a customs house in the quay.

Baku became a center of the eponymous province after the devastating earthquake of 1859 in Shamakha. The population of Baku Governorate began to increase steadily. It is recorded that the number of police stations increased. The first Baku stock exchange had ten brokers, all of Russian nationality.

Oil boom

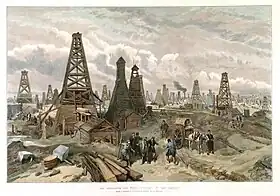

In 1823, the world's first paraffin factory was built in the city, and in 1846, the world's first oil well was drilled in Bibi-Heybat.[19] Javad Melikov from Baku had built the first kerosene factory in 1863. In 1873, the Russian government offered competition for free land, and Baku caught the eye of the Nobel brothers. In 1882, Ludvig Nobel invited technical staff to Baku from Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Germany and founded a colony that he called Villa Petrolea.[20] This colony was located in the "Black City". Bullock-cart drivers used wineskins and flasks to transport oil until the 1870s. In 1883, a Rothschild's plenipotentiary arrived from Paris and created the "Caspian-Black Sea Joint-Stock Company". Famous Baku oil magnates of the era included Musa Nagiyev, Murtuza Mukhtarov, Shamsi Asadullayev, Seid Mirbabayev, and many others.

The companies owned by Musa Nagiyev and Shamsi Asadullayev were the largest of Baku's oil producers. Established respectively in 1887 and 1893, they produced between 7 million and 12 million poods (110 to 200 Gg) of oil annually. The companies owned oil fields, refineries, and tankers. By the beginning of the next century, more than a hundred oil firms operated in Baku.

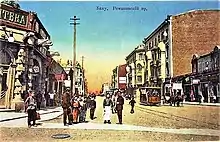

The oil boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries contributed to massive growth of Baku. Between 1856 and 1910 Baku's population grew at a faster rate than that of London, Paris or New York.[21]

Pre-revolutionary period

The second half of the 19th century was notable for its advancement in communication. In 1868, the first telegraph line to Tiflis was established, and in 1879, an under-sea telegraph line connected Baku with Krasnovodsk. In the same year, the Baku-Sabunchi-Surakhany was in operation. The tracks were 520 versts (555 kilometres) from Tiflis and was completed in a relatively short time on 8 May 1883. The first telephone line was in operation in 1886. In 1899, the first horse tramway appeared.

In 1870, a Lutheran-Evangelical community was established in Baku. However, in 1937, the clerics as well as the representatives of other religious communities were banished or shot. The Lutheran community was not revived until 1994, after the fall of the Soviet Union.

In the 1870s, the number of administrative and public institutions had grown, among them a provincial court and arbitration. In the first years of the 20th century, a case considered in the district court won great popularity and lawyers from Petersburg, Moscow, Tiflis, and Kiev became involved because of fabulous fees often received there. The loudest litigations passed with the participation of a certain Karabek, who knew by heart the extensive code of laws of the Russian Empire and remembered all decrees of the Sacred Synod with exact reference numbers and dates.

In the beginning of October 1883, tsar Alexander III with his wife and two sons, accompanied by a huge retinue, arrived to Baku from Tiflis. The railway station had been prepared for the solemn ceremony. The city authorized Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev to welcome Alexander. The visitors examined the oil storage of Nobel brothers, the pump station, and three powerful oil wells of Shamsi Asadullayev. Beginning from the 1890s, Baku provided 95% of the oil production in the Russian Empire and approximately half of world oil production. Within ten years, the city had become the foremost producer of oil overtaking the United States.[22]

In 1894, the city's first water distiller was put into operation.

World War I

In 1914–1917, Baku produced 7 million tons of oil each year, totaling 28,683,000 tons of oil , which constituted 15% of world production at the time. Germany did not trust Turkey in oil matters and transferred General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein from the Middle Eastern front with his troops to Georgia in order to enter Baku, through Ukraine, the Black Sea and Georgia. Great Britain, in February 1918, urgently sent General Lionel Dunsterville with troops to Baku through Anzali to block the German troops. Having studied the Caucasus from the strategic point of view, Dunsterville concluded: "Those who capture Baku, will control the sea. That's why it was necessary for us to invade this city." On 23 August 1918, Lenin in his telegram to Tashkent wrote: "Germans agree to attack Baku provided that we would kick the British out of Baku".

Having been defeated in World War I, Turkey had to withdraw its forces from the borders of Azerbaijan in the middle of November 1918. Led by General William Thomson, British troops of 5,000 soldiers arrived in Baku on 17 November, and martial law was implemented on the capital of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic until "the civil power would be strong enough to release the forces from the responsibility to maintain the public order".

In the same year, Thompson was faced with an enormous challenge to recreate confidence in the economy. His fundamental requirement was to recreate a sound and reliable banking system. He wrote, however: "the political situation in Baku does not permit the opening of a British Bank because this would have increased suspicion and jealousy as to British intentions".

Photo gallery of Old Baku

Soviet Baku

In the spring of 1918, Armenian interests in Baku were protected by the Baku Soviet of People's Commissars, who became known as the 26 Baku Commissars.

In February 1920, the 1st Congress of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan legally took place in Baku and made a decision about preparation of the armed revolt. On 27 April of the same year, units of the Russian 11th Red Army crossed the border of Azerbaijan and began to march towards Baku. Soviet Russia presented the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic with an ultimatum to surrender, and the troops entered Baku the next day, accompanied by Grigory Ordzhonikidze and Sergey Kirov of the Bolshevik Kavbiuro.[23] The city became a capital of the Azerbaijan SSR and underwent many major changes. As a result, Baku played a great role in many branches of the Soviet life. Since about 1921, the city was headed by the Baku City Executive Committee, commonly known in Russian as Bakgorispolkom. Together with the Baku Party Committee (known as the Baksovet), it developed the economic significance of the Caspian metropolis. From 1922 to 1930, Baku was the venue for one of the major Trade fairs of the Soviet Union, serving as a commercial bridgehead to Iran and the Middle East.[24]

On 8 February 1924, the first tram line and two years later the electric railway Baku-Surakhany—the first in the USSR—started to operate.

While being in Baku in May 1925 Russian poet Sergei Yesenin wrote a verse "Farewell to Baku":

Farewell to Baku! I'll see you no more

A sorrow and fright are now in the soul

And a heart under the hand is more painful and closer

And I feel the simple word "friend" more distinctly.

However Yesenin returned to the city on 28 July of the same year.

Maxim Gorkiy wrote after visiting Baku: "The oil fields remained in my memory as a perfect picture of the grave hell. This picture suppressed all the fantastic ideas of depressed mind, I was aware of." Well-known—at that time—industrialist V. Rogozin noted, in relation with the Baku oil fields, that everything there was done "without counting and calculating". In 1940, 22.2 million tons of oil were extracted in Baku which comprised nearly 72% of all the oil extracted in the entire USSR.

In 1941, the trolley bus line started to operate in the city, meanwhile the first buses appeared in Baku in 1928.

World War II

The US Ambassador to France, W. Bullitt, dispatched a telegram to Washington concerning "the possibilities of bombing and demolition of Baku" which were being discussed in Paris at the time. Charles de Gaulle was extremely critical of the plan according to both his wartime and postwar statements. Such ideas, he believed, were made by some "crazy heads that were thinking more of how to destroy Baku than of resisting Berlin". In his report submitted on 22 February 1940, to French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, General Maurice Gamelin believed the Soviets would fall into crisis if those resources were lost. However, during the Soviet-German War, ten defense zones were built around the city to prevent possible German invasion,[25] planned within the Operation Edelweiss.

Even a cake for Hitler was adorned by a map of the Caspian Sea with the letters B-A-K-U spelled out in chocolate cream. After eating the cake, Hitler said: "Unless we get Baku oil, the war is lost".[26]

Post-war period

The first offshore oil platform in the world, originally called "The Black Rocks", was built in 1947 within the city's metropolitan area. In 1960, the first Caucasus house-building plant was built in Baku, and on 25 December 1975, the only plant producing air-conditioners in the Soviet Union was turned over for operation.

In 1964–1968, the level of oil extraction rose to the stable level and comprised about 21 million tons per year.[27] By the 1970s, Azerbaijan became one of the largest producers of grapes, and a champagne factory was subsequently constructed in Baku. In 1981, a record quantity of 15 billion m³ of gas was extracted in Baku.

Independence era

In 1990, Shaumyan rayon of Baku was renamed to Khatai and Ordzhonikidze rayon to Narimanov. In 1991, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Bakgorispolkom as a result, the first independent city mayor Rafael Allahverdiyev was appointed. On 29 April 1992, the names of some more city rayons were changed:

- 26 Baku Commissars to Sabail

- Kirov to Binagadi

- Lenin to Sabunchi

- October to Yasamal.[28]

With the initiatives for saving the city in the 2000s, Baku embarked on a process of restructuring on a scale unseen in its history. Thousands of buildings from Soviet Period were demolished to make way for a green belt on its shores; parks and gardens were built on the land claimed by filling up the beaches of the Baku Bay. Improvements were made in the general cleaning, maintenance, garbage collection fields and these services are now at Western European standards. The city is growing dynamically and developing at full speed on an east-west axis along the shores of the Caspian Sea.

Appearance

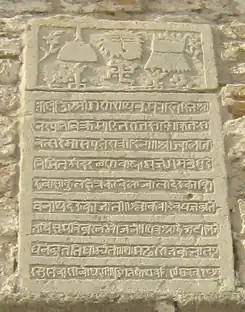

According to a stone inscription, the city's first fortified walls were erected by Shirvanshah Manuchehr II. The fortifications that once surrounded Baku were repeatedly destroyed due to invasions. These fortifications were composed of multiple lines of walls interspersed with moats that connected to channels leading to the Caspian Sea. These fortifications featured drawbridges which were raised at twilight. In 1078 the Broken Tower (Sınıq-Qala), the city's first mosque, was built. The construction of the city's historical core, named the Inner City, began in the 14th century.

For many centuries, Baku engaged in trade with its neighbors. Trade was made possible by caravan routes and sea ways. Bukhara and Indian caravan-sheds within the Inner City testified that in the 14th to 16th centuries, Baku conducted trade with India and Central Asia.

One of the first prominent Baku architects, Kasum-bek Gadjibababekov, is credited for the city's layout which was admired by Russian and European planners. Due to the city's topography, streets in Baku at this time were laid in steps. The unpaved streets were sometimes shrouded in clouds of dust for weeks at a time when the northern wind, known as Khazri, or the southern wind, Gilavar, blew.

The Russian traveller I. Beryozin, who visited Baku in the middle of the 19th century described the city streets as "...narrow and entangled, that after a month in Baku I did not know, where a street began and where it ended".

In 1859, the construction of Baku's city port began, and, in 1861, A. Ulski, Captain-lieutenant of the Russian Fleet, took the city's first photograph. Drainage was installed in 1878. British civil engineer William Heerlein Lindley, who worked in the city from 1899 until his death in 1917, coordinated the building of Baku's water supply system.

On 3 May (21 April O.S.), 1896, the notable Nobel family laid the foundation stone for the city's Lutheran church. It was one of the few places of worship that was not demolished during Stalin's rule. Since then its primary use has been for concerts—the church houses one of the few pipe organs in Baku. A Molokan meeting-house functions on the so-called Molokanka, near the former Chapayev Street.[29]

In 1898, German civil engineer Nicholas von der Nonne developed the first professional plan for the growth of Baku. In the early 1960s, during the term of Baku mayor Alish Lemberanski, the city's micro-regions (suburbs) were created outside of Baku, and old, crumbling buildings gave way to Soviet-style architecture. Narrow streets were widened into boulevards to accommodate more vehicles. In April 1960, as part of the festivities during the 40th anniversary of the Soviet Union, a walking tour was arranged to show the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev a brand-new walkway made of colorful blue and pink concrete slabs. In fact, Khrushchev never saw the walkway, but typical buildings of this period are still called khruschovki, from Russian: хрущëвки.

Recently, the current mayor of Baku, Hajibala Abutalybov, has been criticized for the city's decline in appearance.[30][31]

Baku has also announced its intentions to bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. Baku was the host city for the Eurovision Song Contest 2012.

Toponymy

Nearly every street that brings to mind anything relating to the Soviet Union has been officially changed. More than 225 names of streets have been renamed since 1988; however, some people still use the old names. Namely, the first street ever to be built outside the Inner City, originally called Nikolayevskaya after Nicolas I, was renamed to Parlaman Kuchesi, because the Parliament of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic held its meeting in a building located at that street, then during soviet era it became Kommunisticheskaya Ulitsa and now is called İstiqlaliyyet Kuchesi (Azeri: "independence").

Notable streets

| Former name(s) | Current name |

|---|---|

| Armyanskaya, Maxim Gorky (in 1928–1997) | Mirza Ibragimov (from 1997) |

| Aziatskaya, Petr Montin | Alovsat Quliyev (from 1991) |

| Balakhanskaya, Basin | Fizuli (from 1989) |

| Baryatinskaya, Fioletov (in 1923–1991) | Academician Abdulkerim Alizade (from 1991) |

| Bazarnaya | Husi Hajiyev |

| Bolshaya Minaretnaya | Asaf Zeynallı (from 1939) |

| Bondarnaya, Dmitrova (in 1939–1991) | Shamsi Badalbeyli (from 1991) |

| Telefonnaya, Lindley (in 1918–1923), 28 April (in 1923–1992) | 28 May (from 1992) |

| Verkhnyaya Priyutskaya, Ketzkhoveli (in 1939–1991) | Academician Shamil Azizbekov (from 1991) |

| Yuryevskaya, Sovetskaya (from 1929 to 1991) | Narimanov avenue (from 1991) |

Old squares names

| Former name(s) | Current name |

|---|---|

| Bazarnaya, Quba Meydanı, Dimitrov | Fizuli |

| Birzhevaya, Svobody, 26 Baku Commisars | Azadlığ |

| Parapet, Karl Marx | Fountain Square |

| Vorontsovskaya | Kemur meydanı |

Old parks names

| Former name(s) | Current name |

|---|---|

| Bailov Park | Qafur Mamedov Park |

| Dzerzhinskiy Park | Shakhriyar Park |

| Dzhaparidze Park | Koroghlu Park |

| Kirov Park | Martyrs' Lane |

| Molokan Garden | Khagani Garden |

| Officers Park | Dədə Qorğud |

City mayors

The mayorship has been interrupted mainly by the rules of General-Governor, City Council, People's Commissars Council and Bakgorispolkom.

| Mayor | Term of office |

|---|---|

| Pavel Parsadanovich Argutinsky-Dolgorukov | 1846[32] |

| Iosif Dzhakeli | 14 January 1878 – January 1879 |

| Stanislav Despot-Zenovich | 1879–1881 (acting as mayor), 1881–1893 |

| Khristofor Antonov | 1893–? (acting as mayor) |

| Konstantin Iretskiy | 1896–? |

| Nikolaus von der Nonne | 1898 - 1901 |

| Alexander Novikov | 1903–1904 |

| Kamil Safaraliyev | 1904–1906[33] |

| Pyotr Martynov | 1906–?, 1910 (acting as mayor) |

| Mikhail Folbaum | 1908 |

| Fyodor Golovin | 1912 |

| Sanan Alizade | 18 October 1991– 15 April 1992 |

| Aghasalim Baghirov | 15 April 1992 – 4 July 1992 |

| Rauf Gulmammadov | 4 July 1992 - 3 July 1993 |

| Rafael Allahverdiyev | 3 July 1993 – 16 October 2000 |

| Muhammed Abbasov | 16 October 2000 – 30 January 2001 (did locum) |

| Hajibala Abutalybov | 30 January 2001 – 21 April 2018 |

| Eldar Azizov | 15 November 2018 – present |

See also

References

- ↑ Ашурбейли Сара. История города Баку: период средневековья. Баку, Азернешр, 1992

- ↑ Ашурбейли Сара. История города Баку.

- ↑ Ган К.Ф. Oпыть объяснения кавказских географических названий. Тифлис, 1909

- 1 2 The Name “Baku”

- ↑ Город Баку... Retrieved on 24 June 2006

- ↑ Ancient Observatory of Absheron. Gobustan, No 3 (1973)

- ↑ Cass, Frank (1918). The Battle for Baku. London: Taylor and Francais online.

- ↑ "Return of the Relics of the Apostle Bartholomew from Anastasiopolis to Lipari".

The Apostle Bartholomew suffered for Christ in Armenian Albanus (now Baku) in the year 71, where his holy relics were.

- ↑ City of Baku – Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan

- ↑ Город-крепость Баку Archived 20 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 June 2006

- ↑ Dodds, Henry (1977). Baku, and Eventful History. New York: Arno press.

- ↑ "Ичери Шехер": быть или не быть Archived 20 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 June 2006

- ↑ Yusif Mir-Babayev. Azerbaijan's Oil History. A Chronology Leading up to the Soviet Era. Retrieved on 24 June 2006

- ↑ SOCAR Section: Baku Oil and the Cycle of History Retrieved on 4 July 2006

- ↑ Шаммазов А.М. История развития нефтегазовой промышленности. 1999

- ↑ Taleh Ziyadov (2012). Azerbaijan as a Regional Hub in Central Eurasia: Strategic Assessment of Euro-Asian Trade and Transportation. Taleh Ziyadov. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-9952-34-801-9.

- ↑ William Edward David Allen and Paul Muratoff. "Caucasian Battlefields: A History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border 1828–1921. (Cambridge University Press, 2010). 20.

- ↑ James B. Minahan (2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8.

- ↑ Makey, John. Baku oil and Transcaucasian Pipelines. JSTOR.

- ↑ "Товарищество нефтяного производства братьев Нобель (БраНобель)". Ourbaku Encyclopedia. Ourbaku e.V.

- ↑ Lattu, Kristan (1973). History of Rocketry. Amsterdam: American Astronautical Society.

- ↑ Jamil Hasanov. The Struggle For Azerbaijani Oil At The End Of World War I Archived 28 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2 July 2006

- ↑ Audrey L. Altstadt (1992), The Azerbaijani Turks, Stanford, Calif: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, ISBN 0817991816, OCLC 24846708, OL 1560533M, 0817991816

- ↑ Etienne Forestier-Peyrat, ″Red Passage to Iran: The Baku Trade Fair and the Unmaking of the Azerbaijani Borderland, 1922–1930″, Ab Imperio, Vol 2013, Issue 4, pp. 79–112.

- ↑ Werth, Alexander. Russia at War 1941–1945

- ↑ Big Oil Comes Back To Baku Natural History Retrieved on 4 July 2006

- ↑ Baku and Oil. The Soviet Period Retrieved on 24 June 2006

- ↑ г. Баку Archived 24 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 4 July 2006

- ↑ Пасха по-молокански Retrieved on 30 June 2006

- ↑ Baku Mayor Under Fire Retrieved on 25 June 2006

- ↑ HRW World Report 2002 Retrieved on 25 June 2006

- ↑ "OurBaku : Liste des Administrateurs du Comté de Bakou". www.ourbaku.com (in Russian). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ↑ Altstadt, Audrey L. (1992). The Azerbaijani Turks: power and identity under Russian rule. Hoover Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-8179-9182-4.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Jedidiah Morse; Richard C. Morse (1823), "Baku", A New Universal Gazetteer (4th ed.), New Haven: S. Converse

- F. H. Trevithick (1886), A Sketchy Report on the Petroleum Industry at Baku, Cairo: National Printing Office, OL 23382205M

- Published in the 20th century

- James Dodds Henry (1905), Baku: an Eventful History, London: A. Constable & Co., OCLC 24454390, OL 6972546M

- Alstadt, Audrey L. The Azerbaijani Bourgeoisie and the Cultural-Enlightenment Movement in Baku: First Steps Toward Nationalism. 1983

- Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Baku". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Michael R.T. Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley, eds. (2008), "Baku", Cities of the Middle East and North Africa, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO

- "Baku". Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2009.

Azerbaijani literature

- Sarabski, Hüseynqulu. Köhnə Bakı. Bakı, 1958.

Russian literature

- Манаф Сулейманов. Дни минувшие.

- Ашурбейли, Сара. История города Баку. Период средневековья. Б., Азернешр, 1992.

- Тагиев Ф. А. История города Баку в первой половине XIX века (1806–1859). Б., Элм, 1999.

- Мир-Бабаев, Мир-Юсиф. Краткая история азербайджанской нефти. Б., SOCAR, 2008.

External links

- Khadija Aghabeyli. Growing Up in Baku's Old City

- The Architectural Face of Modern Baku

- Chronology of the Baku oil industry

- How Baku Got Its Water

- ArchNet.org. "Baku". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- "Baku". Islamic Cultural Heritage Database. Istanbul: Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)