%252C_c._190-200_AD%252C_Ny_Carlsberg_Glyptotek%252C_Copenhagen.jpg.webp)

The modius is a type of flat-topped cylindrical headdress or crown found in ancient Egyptian art and art of the Greco-Roman world. The name was given by modern scholars based on its resemblance to the jar used as a Roman unit of dry measure,[1][2] but it probably does represent a grain-measure, and symbolizing one's ability to learn new information by having an open mind with an empty cup. Serapis was the main idol/figurehead at the Library of Alexandria during the ancient Egyptian & Roman alliance.

The modius is worn by certain deities, including the Eleusinian deities and their Roman counterparts, the Ephesian Artemis and certain other forms of the goddess,[3] Hecate, and Serapis.[4] On some deities it represents fruitfulness.[5]

It is thought to be a form mostly restricted to supernatural beings in art, and rarely worn in real life, with two probable exceptions. A tall modius is part of the complex headdress used for depictions of Egyptian royal women, often ornamented variously with symbols, vegetative motifs, and the uraeus.[6] It was also the distinctive headdress of Palmyrene priests.[7][8]

Serapis wearing the modius

Serapis wearing the modius.jpg.webp)

Sitamun, daughter of Amenhotep III, depicted wearing a modius on her throne. From the Tomb of Yuya and Thuya, 18th Dynasty

Sitamun, daughter of Amenhotep III, depicted wearing a modius on her throne. From the Tomb of Yuya and Thuya, 18th Dynasty Statue of Meritamen, daughter of Ramesses II, wearing a modius decorated with uraei. From the Ramesseum, 19th Dynasty.

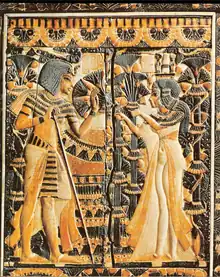

Statue of Meritamen, daughter of Ramesses II, wearing a modius decorated with uraei. From the Ramesseum, 19th Dynasty. Ankhesenamun depicted on a box lid wearing a modius topped by a head cone and two uraei while presenting bouquets to her husband, Tutankhamun. Tomb of Tutankhamun, 18th Dynasty.

Ankhesenamun depicted on a box lid wearing a modius topped by a head cone and two uraei while presenting bouquets to her husband, Tutankhamun. Tomb of Tutankhamun, 18th Dynasty.

See also

References

- ↑ Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante, The World of Roman Costume (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), p. 245

- ↑ Irene Bald Romano, Classical Sculpture: Catalogue of the Cypriot, Greek, And Roman Stone Sculpture in the University Of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology, 2006), p. 294.

- ↑ Joseph Eddy Fontenrose, Didyma: Apollo's Oracle, Cult, and Companions pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, Hellenistic Sculpture: The Styles of ca. 331–200 B.C. (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), p. 95.

- ↑ Fontenrose, Didyma, p. 131.

- ↑ Bryan, "A Newly Discovered Statue of a Queen," p 36ff.; Paul Edmund Stanwick, Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings As Egyptian Pharaohs (University of Texas Press, 2002), p. 35 et passim.

- ↑ Romano, Classical Sculpture, p. 294

- ↑ Lucinda Dirven, The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria (Brill, 1999), pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Harmatta, János (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 326. ISBN 978-81-208-1408-0.