The toga (/ˈtoʊɡə/, Classical Latin: [ˈt̪ɔ.ɡa]), a distinctive garment of ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between 12 and 20 feet (3.7 and 6.1 m) in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tradition, it is said to have been the favored dress of Romulus, Rome's founder; it was also thought to have originally been worn by both sexes, and by the citizen-military. As Roman women gradually adopted the stola, the toga was recognized as formal wear for male Roman citizens.[1] Women found guilty of adultery and women engaged in prostitution might have provided the main exceptions to this rule.[2]

The type of toga worn reflected a citizen's rank in the civil hierarchy. Various laws and customs restricted its use to citizens, who were required to wear it for public festivals and civic duties.

From its probable beginnings as a simple, practical work-garment, the toga became more voluminous, complex, and costly, increasingly unsuited to anything but formal and ceremonial use. It was and is considered ancient Rome's "national costume"; as such, it had great symbolic value; however even among Romans, it was hard to put on, uncomfortable and challenging to wear correctly, and never truly popular. When circumstances allowed, those otherwise entitled or obliged to wear it opted for more comfortable, casual garments. It gradually fell out of use, firstly among citizens of the lower class, then those of the middle class. Eventually, it was worn only by the highest classes for ceremonial occasions.

Varieties

.png.webp)

The toga was an approximately semi-circular woollen cloth, usually white, worn draped over the left shoulder and around the body: the word "toga" probably derives from tegere, to cover. It was considered formal wear and was generally reserved for citizens. The Romans considered it unique to themselves, thus their poetic description by Virgil and Martial as the gens togata ('toga-wearing race').[3] There were many kinds of toga, each reserved by custom to a particular usage or social class.

- Toga virilis ("toga of manhood") also known as toga alba or toga pura: A plain white toga, worn on formal occasions by adult male commoners, and by senators not having a curule magistracy. It represented adult male citizenship and its attendant rights, freedoms and responsibilities; traditionally given at a father's discretion to his son during the feast of Liberalia, to mark the onset of puberty and legal "coming of age", at around 14 years of age or more.[4][5]

- Toga praetexta: a white toga with a broad purple stripe on its border, worn over a tunic with two broad, vertical purple stripes. It was formal costume for:

- Curule magistrates in their official functions, and traditionally, the Kings of Rome.[6]

- Freeborn boys, and some freeborn girls, before they came of age.[7] It marked their protection by law from sexual predation and immoral or immodest influence. A praetexta was thought effective against malignant magic, as were a boy's bulla, and a girl's lunula.[8][9]

- Some priesthoods, including the Pontifices, Tresviri Epulones, the augurs, and the Arval brothers.[10]

- Toga candida: "Bright toga"; a toga rubbed with chalk to a dazzling white, worn by candidates (from Latin candida, "pure white") for public office.[11] Thus Persius speaks of a cretata ambitio, "chalked ambition". Toga candida is the etymological source of the word candidate.

- Toga pulla: a "dark toga" was supposed to be worn by mourners at elite funerals. A toga praetexta was also acceptable as mourning wear, if turned inside out to conceal its stripe; so was a plain toga pura.[12] Wearing a toga pulla at the feast that ended mourning was irreligious, ignorant, or plain bad manners. Cicero makes a distinction between the toga pulla and an ordinary toga deliberately "dirtied" by its wearer as a legitimate mark of protest or supplication.[13]

- Toga picta ("painted toga"): Dyed solid purple, decorated with imagery in gold thread, and worn over a similarly-decorated tunica palmata; used by generals in their triumphs. During the Empire, it was worn by consuls and emperors. Over time, it became increasingly elaborate, and was combined with elements of the consular trabea.[14]

- Trabea, associated with citizens of equestrian rank; thus their description as trabeati in some contemporary Roman literature. It may have been a shorter form of toga, or a cloak, wrap or sash worn over a toga. It was white with some form of decoration. In the later Imperial era, trabea refers to elaborate forms of consular dress. Some later Roman and post-Roman sources describe it as solid purple or red, either identifying or confusing it with the dress worn by the ancient Roman kings (also used to clothe images of the gods) or reflecting changes in the trabea itself. More certainly, equites wore an angusticlavia, a tunic with narrow, vertical purple stripes, at least one of which would have been visible when worn with a toga or trabea, whatever its form.[15]

- Laena, a long, heavy cloak worn by Flamen priesthoods, fastened at the shoulder with a brooch. A lost work by Suetonius describes it as a toga made "duplex" (doubled by folding over upon itself).[16][17]

As "national dress"

The toga's most distinguishing feature was its semi-circular shape, which sets it apart from other cloaks of antiquity like the Greek himation or pallium. To Rothe, the rounded form suggests an origin in the very similar, semi-circular Etruscan tebenna.[18] Norma Goldman believes that the earliest forms of all these garments would have been simple, rectangular lengths of cloth that served as both body-wrap and blanket for peasants, shepherds and itinerant herdsmen.[19] Roman historians believed that Rome's legendary founder and first king, the erstwhile shepherd Romulus, had worn a toga as his clothing of choice; the purple-bordered toga praetexta was supposedly used by Etruscan magistrates, and introduced to Rome by her third king, Tullus Hostilius.[20]

In the wider context of classical Greco-Roman fashion, the Greek enkyklon (Greek: ἔγκυκλον, "circular [garment]") was perhaps similar in shape to the Roman toga, but never acquired the same significance as a distinctive mark of citizenship.[21] The 2nd-century diviner Artemidorus Daldianus in his Oneirocritica derived the toga's form and name from the Greek tebennos (τήβεννος), supposedly an Arcadian garment invented by and named after Temenus.[22][23] Emilio Peruzzi claims that the toga was brought to Italy from Mycenaean Greece, its name based on Mycenaean Greek te-pa, referring to a heavy woollen garment or fabric.[24]

In civil life

Roman society was strongly hierarchical, stratified and competitive. Landowning aristocrats occupied most seats in the senate and held the most senior magistracies. Magistrates were elected by their peers and "the people"; in Roman constitutional theory, they ruled by consent. In practice, they were a mutually competitive oligarchy, reserving the greatest power, wealth and prestige for their class. The commoners who made up the vast majority of the Roman electorate had limited influence on politics, unless barracking or voting en masse, or through representation by their tribunes. The Equites (sometimes loosely translated as "knights") occupied a broadly mobile, mid-position between the lower senatorial and upper commoner class. Despite often extreme disparities of wealth and rank between the citizen classes, the toga identified them as a singular and exclusive civic body.

Togas were relatively uniform in pattern and style but varied significantly in the quality and quantity of their fabric, and the marks of higher rank or office. The highest-status toga, the solidly purple, gold-embroidered toga picta could be worn only at particular ceremonies by the highest-ranking magistrates. Tyrian purple was supposedly reserved for the toga picta, the border of the toga praetexta, and elements of the priestly dress worn by the inviolate Vestal Virgins. It was colour-fast, extremely expensive and the "most talked-about colour in Greco-Roman antiquity".[26] Romans categorised it as a blood-red hue, which sanctified its wearer. The purple-bordered praetexta worn by freeborn youths acknowledged their vulnerability and sanctity in law. Once a boy came of age (usually at puberty) he adopted the plain white toga virilis; this meant that he was free to set up his own household, marry, and vote.[27][28] Young girls who wore the praetexta on formal occasions put it aside at menarche or marriage, and adopted the stola.[29] Even the whiteness of the toga virilis was subject to class distinction. Senatorial versions were expensively laundered to an exceptional, snowy white; those of lower ranking citizens were a duller shade, more cheaply laundered.[30]

Citizenship carried specific privileges, rights and responsibilities.[31] The formula togatorum ("list of toga-wearers") listed the various military obligations that Rome's Italian allies were required to supply to Rome in times of war. Togati, "those who wear the toga", is not precisely equivalent to "Roman citizens", and may mean more broadly "Romanized".[32] In Roman territories, the toga was explicitly forbidden to non-citizens; to foreigners, freedmen, and slaves; to Roman exiles;[33] and to men of "infamous" career or shameful reputation; an individual's status should be discernable at a glance.[34] A freedman or foreigner might pose as a togate citizen, or a common citizen as an equestrian; such pretenders were sometimes ferreted out in the census. Formal seating arrangements in public theatres and circuses reflected the dominance of Rome's togate elect. Senators sat at the very front, equites behind them, common citizens behind equites; and so on, through the non-togate mass of freedmen, foreigners, and slaves.[35] Imposters were sometimes detected and evicted from the equestrian seats.[36]

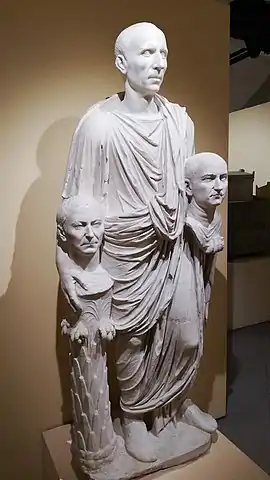

Various anecdotes reflect the toga's symbolic value. In Livy's history of Rome, the patrician hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, retired from public life and clad (presumably) in tunic or loincloth, is ploughing his field when emissaries of the Senate arrive, and ask him to put on his toga. His wife fetches it and he puts it on. Then he is told that he has been appointed dictator. He promptly heads for Rome.[37] Donning the toga transforms Cincinnatus from rustic, sweaty ploughman – though a gentleman nevertheless, of impeccable stock and reputation – into Rome's leading politician, eager to serve his country; a top-quality Roman.[38] Rome's abundant public and private statuary reinforced the notion that all Rome's great men wore togas, and must always have done so.[39][40]

Work and leisure

Traditionalists idealised Rome's urban and rustic citizenry as descendants of a hardy, virtuous, toga-clad peasantry, but the toga's bulk and complex drapery made it entirely impractical for manual work or physically active leisure. The toga was heavy, "unwieldy, excessively hot, easily stained, and hard to launder".[41] It was best suited to stately processions, public debate and oratory, sitting in the theatre or circus, and displaying oneself before one's peers and inferiors while "ostentatiously doing nothing".[42]

Every male Roman citizen was entitled to wear some kind of toga – Martial refers to a lesser citizen's "small toga" and a poor man's "little toga" (both togula),[43] but the poorest probably had to make do with a shabby, patched-up toga, if he bothered at all.[44] Conversely, the costly, full-length toga seems to have been a rather awkward mark of distinction when worn by "the wrong sort". The poet Horace writes "of a rich ex-slave 'parading from end to end of the Sacred Way in a toga three yards long' to show off his new status and wealth."[45]

In the early 2nd century AD, the satirist Juvenal claimed that "in a great part of Italy, no-one wears the toga, except in death"; in Martial's rural idyll there is "never a lawsuit, the toga is scarce, the mind at ease".[46][47] Most citizens who owned a toga would have cherished it as a costly material object, and worn it when they must for special occasions. Family, friendships and alliances, and the gainful pursuit of wealth through business and trade would have been their major preoccupations, not the otium (cultured leisure) claimed as a right by the elite.[48][49] Rank, reputation and Romanitas were paramount, even in death, so almost invariably, a male citizen's memorial image showed him clad in his toga. He wore it at his funeral, and it probably served as his shroud.[50]

Despite the overwhelming quantity of Roman togate portraits at every social level, and in every imaginable circumstance, at most times Rome's thoroughfares would have been crowded with citizens and non-citizens in a variety of colourful garments, with few togas in evidence. Only a higher-class Roman, a magistrate, would have had lictors to clear his way, and even then, wearing a toga was a challenge. The toga's apparent natural simplicity and "elegant, flowing lines" were the result of diligent practice and cultivation; to avoid an embarrassing disarrangement of its folds, its wearer had to walk with measured, stately gait,[41] yet with virile purpose and energy. If he moved too slowly, he might seem aimless, "sluggish of mind" - or, worst of all, "womanly".[51] Vout (1996) suggests that the toga's most challenging qualities as garment fitted the Romans' view of themselves and their civilization. Like the empire itself, the peace that the toga came to represent had been earned through the extraordinary and unremitting collective efforts of its citizens, who could therefore claim "the time and dignity to dress in such a way".[52]

Patronage and salutationes

Patronage was a cornerstone of Roman politics, business and social relationships. A good patron offered advancement, security, honour, wealth, government contracts and other business opportunities to his client, who might be further down in the social or economic scale, or more rarely, his equal or superior.[54] A good client canvassed political support for his patron, or his patron's nominee; he advanced his patron's interests using his own business, family and personal connections. Freedmen with an aptitude for business could become extremely wealthy; but to negotiate citizenship for themselves, or more likely their sons, they had to find a patron prepared to commend them. Clients seeking patronage had to attend the patron's early-morning formal salutatio ("greeting session"), held in the semi-public, grand reception room (atrium) of his family house (domus).[55] Citizen-clients were expected to wear the toga appropriate to their status, and to wear it correctly and smartly or risk affront to their host.[56]

Martial and his friend Juvenal suffered the system as clients for years, and found the whole business demeaning. A client had to be at his patron's beck and call, to perform whatever "togate works" were required; and the patron might even expect to be addressed as "domine" (lord, or master); a citizen-client of the equestrian class, superior to all lesser mortals by virtue of rank and costume, might thus approach the shameful condition of dependent servitude. For a client whose patron was another's client, the potential for shame was still worse. Even as a satirical analogy, the equation of togate client and slave would have shocked those who cherished the toga as a symbol of personal dignity and auctoritas – a meaning underlined during the Saturnalia festival, when the toga was "very consciously put aside", in a ritualised, strictly limited inversion of the master-slave relationship.[57]

Patrons were few, and most had to compete with their peers to attract the best, most useful clients. Clients were many, and those of least interest to the patron had to scrabble for notice among the "togate horde" (turbae togatae). One in a dirty or patched toga would likely be subject to ridicule; or he might, if sufficiently dogged and persistent, secure a pittance of cash, or perhaps a dinner. When the patron left his house to conduct his business of the day at the law courts, forum or wherever else, escorted (if a magistrate) by his togate lictors, his clients must form his retinue. Each togate client represented a potential vote:[58] to impress his peers and inferiors, and stay ahead in the game, a patron should have as many high-quality clients as possible; or at least, he should seem to. Martial has one patron hire a herd (grex) of fake clients in togas, then pawn his ring to pay for his evening meal.[59][60]

The emperor Marcus Aurelius, rather than wear the "dress to which his rank entitled him" at his own salutationes, chose to wear a plain white citizen's toga instead; an act of modesty for any patron, unlike Caligula, who wore a triumphal toga picta or any other garment he chose, according to whim; or Nero, who caused considerable offence when he received visiting senators while dressed in a tunic embroidered with flowers, topped off with a muslin neckerchief.[61]

Oratory

In oratory, the toga came into its own. Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria (circa 95 AD) offers advice on how best to plead cases at Rome's law-courts, before the watching multitude's informed and critical eye. Effective pleading was a calculated artistic performance, but must seem utterly natural. First impressions counted; the lawyer must present himself as a Roman should: "virile and splendid" in his toga, with statuesque posture and "natural good looks". He should be well groomed – but not too well; no primping of the hair, jewellery or any other "feminine" perversions of a Roman man's proper appearance. Quintilian gives precise instructions on the correct use of the toga – its cut, style, and the arrangements of its folds. Its fabric could be old-style rough wool, or new and smoother if preferred – but definitely not silk. The orator's movements should be dignified, and to the point; he should move only as he must, to address a particular person, a particular section of the audience. He should employ to good effect that subtle "language of the hands" for which Roman oratory was famed; no extravagant gestures, no wiggling of the shoulders, no moving "like a dancer".[63][64]

To a great extent, the toga itself determined the orator's style of delivery: "we should not cover the shoulder and the whole of the throat, otherwise our dress will be unduly narrowed and will lose the impressive effect produced by breadth at the chest. The left arm should only be raised so far as to form a right angle at the elbow, while the edge of the toga should fall in equal lengths on either side." If, on the other hand, the "toga falls down at the beginning of our speech, or when we have only proceeded but a little way, the failure to replace it is a sign of indifference, or sloth, or sheer ignorance of the way in which clothes should be worn". By the time he had presented his case, the orator was likely to be hot and sweaty; but even this could be employed to good effect.[65]

In public morals

Roman moralists "placed an ideological premium on the simple and the frugal".[66] Aulus Gellius claimed that the earliest Romans, famously tough, virile and dignified, had worn togas with no undergarment; not even a skimpy tunic.[67] Towards the end of the Republic, the arch-conservative Cato the Younger favoured the shorter, ancient Republican type of toga; it was dark and "scanty" (exigua), and Cato wore it without tunic or shoes; all this would have been recognised as an expression of his moral probity.[68] Die-hard Roman traditionalists deplored an ever-increasing Roman appetite for ostentation, "un-Roman" comfort and luxuries, and sartorial offences such as Celtic trousers, brightly coloured Syrian robes and cloaks. The manly toga itself could signify corruption, if worn too loosely, or worn over a long-sleeved, "effeminate" tunic, or woven too fine and thin, near transparent.[69] Appian's history of Rome finds its strife-torn Late Republic tottering at the edge of chaos; most seem to dress as they like, not as they ought: "For now the Roman people are much mixed with foreigners, there is equal citizenship for freedmen, and slaves dress like their masters. With the exception of the Senators, free citizens and slaves wear the same costume."[70] The Augustan Principate brought peace, and declared its intent as the restoration of true Republican order, morality and tradition.

(Via Labicana Augustus).

Augustus was determined to bring back "the traditional style" (the toga). He ordered that any theatre-goer in dark (or coloured or dirty) clothing be sent to the back seats, traditionally reserved for those who had no toga; ordinary or common women, freedmen, low-class foreigners and slaves. He reserved the most honourable seats, front of house, for senators and equites; this was how it had always been, before the chaos of the civil wars; or rather, how it was supposed to have been. Infuriated by the sight of a darkly clad throng of men at a public meeting, he sarcastically quoted Virgil at them, "Romanos, rerum dominos, gentemque togatam " ("Romans, lords of the world and the toga-wearing people"), then ordered that in future, the aediles ban anyone not wearing the toga from the Forum and its environs – Rome's "civic heart".[71] Augustus' reign saw the introduction of the toga rasa, an ordinary toga whose rough fibres were teased from the woven nap, then shaved back to a smoother, more comfortable finish. By Pliny's day (circa 70 AD) this was probably standard among the elite.[72] Pliny also describes a glossy, smooth, lightweight but dense fabric woven from poppy-stem fibres and flax, in use from at least the time of the Punic Wars. Though probably appropriate for a "summer toga", it was criticised for its improper luxuriance.[73]

Women

Some Romans believed that in earlier times, both genders and all classes had worn the toga. Radicke (2002) claims that this belief goes back to a Late Antique scholiast misreading of earlier Roman writings.[74][75] Women could also be citizens, but by the mid-to-late Republican era, respectable women were stolatae (stola-wearing), expected to embody and display an appropriate set of female virtues: Vout cites pudicitia and fides as examples. Women's adoption of the stola may have paralleled the increasing identification of the toga with citizen men, but this seems to have been a far from straightforward process. An equestrian statue, described by Pliny the Elder as "ancient", showed the early Republican heroine Cloelia on horseback, wearing a toga.[76] The unmarried daughters of respectable, reasonably well-off citizens sometimes wore the toga praetexta until puberty or marriage, when they adopted the stola,[77] which they wore over a full-length, usually long-sleeved tunic.

Higher-class female prostitutes (meretrices) and women divorced for adultery were denied the stola. Meretrices might have been expected or perhaps compelled, at least in public, to wear the "female toga" (toga muliebris).[78] This use of the toga appears unique; all others categorised as "infamous and disreputable" were explicitly forbidden to wear it. In this context, modern sources understand the toga – or perhaps merely the description of particular women as togata – as an instrument of inversion and realignment; a respectable (thus stola-clad) woman should be demure, sexually passive, modest and obedient, morally impeccable. The archetypical meretrix of Roman literature dresses gaudily and provocatively. Edwards (1997) describes her as "antithetical to the Roman male citizen".[2] An adulterous matron betrayed her family and reputation; and if found guilty, and divorced, the law forbade her remarriage to a Roman citizen. In the public gaze, she was aligned with the meretrix.[79][80] When worn by a woman in this later era, the toga would have been a "blatant display" of her "exclusion from the respectable Roman hierarchy".[2] However, the view that a convicted adulteress (moecha damnata) actually wore a toga in public has been challenged; Radicke believes that the only prostitutes who could be made to wear particular items of clothing were unfree, compelled by their owners or pimps to wear the relatively shorter, "skimpy", less costly toga exigua, more revealing, easily opened and thus convenient to their profession.[75]

Roman military

Until the so-called "Marian reforms" of the Late Republic, the lower ranks of Rome's military forces were "farmer-soldiers", a militia of citizen smallholders conscripted for the duration of hostilities,[81] expected to provide their own arms and armour. Citizens of higher status served in senior military posts as a foundation for their progress to high civil office (see cursus honorum). The Romans believed that in Rome's earliest days, its military had gone to war in togas, hitching them up and back for action by using what became known as the "Gabine cinch".[82] In 206 BC, Scipio Africanus was sent 1,200 togas and 12,000 tunics for his operations in North Africa. As part of a peace settlement of 205 BC, two formerly rebellious Spanish tribes provided Roman troops with togas and heavy cloaks. In the Macedonian campaign of 169 BC, the army was sent 6,000 togas and 30,000 tunics.[83] From at least the mid-Republic on, the military reserved their togas for formal leisure and religious festivals; the tunic and sagum (heavy rectangular cloak held on the shoulder with a brooch) were used or preferred for active duty.

.jpg.webp)

Late republican practice and legal reform allowed the creation of standing armies, and opened a military career to any Roman citizen or freedman of good reputation.[84] A soldier who showed the requisite "disciplined ferocity" in battle and was held in esteem by his peers and superiors could be promoted to higher rank: a plebeian could achieve equestrian status.[85] Non-citizens and foreign-born auxiliaries given honourable discharge were usually granted citizenship, land or stipend, the right to wear the toga, and an obligation to the patron who had granted these honours; usually their senior officer. A dishonourable discharge meant infamia.[86] Colonies of retired veterans were scattered throughout the Empire. In literary stereotype, civilians are routinely bullied by burly soldiers, inclined to throw their weight around.[87]

Though soldiers were citizens, Cicero typifies the former as "sagum wearing" and the latter as "togati". He employs the phrase cedant arma togae ("let arms yield to the toga"), meaning "may peace replace war", or "may military power yield to civilian power", in the context of his own uneasy alliance with Pompey. He intended it as metonym, linking his own "power to command" as consul (imperator togatus) with Pompey's as general (imperator armatus); but it was interpreted as a request to step down. Cicero, having lost Pompey's ever-wavering support, was driven to exile.[88] In reality, arms rarely yielded to civilian power. During the early Roman Imperial era, members of the Praetorian Guard (the emperor's personal guard as "First Citizen", and a military force under his personal command), concealed their weapons under white, civilian-style togas when on duty in the city, offering the reassuring illusion that they represented a traditional Republican, civilian authority, rather than the military arm of an Imperial autocracy.[84][89]

In religion

Citizens attending Rome's frequent religious festivals and associated games were expected to wear the toga.[83] The toga praetexta was the normal garb for most Roman priesthoods, which tended to be the preserve of high status citizens. When offering sacrifice, libation and prayer, and when performing augury, the officiant priest covered his head with a fold of his toga, drawn up from the back: the ritual was thus performed capite velato (with covered head). This was believed a distinctively Roman form,[90] in contrast to Etruscan, Greek and other foreign practices. The Etruscans seem to have sacrificed bareheaded (capite aperto).[91] In Rome, the so-called ritus graecus ("Greek rite") was used for deities believed Greek in origin or character; the officiant, even if a Roman citizen, wore Greek-style robes with wreathed or bare head, not the toga.[92] It has been argued that the Roman expression of piety capite velato influenced Paul's prohibition against Christian men praying with covered heads: "Any man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head."[93]

An officiant capite velato who needed free use of both hands to perform ritual—as while plowing the sulcus primigenius undertaken at the founding of new colonies—could employ the "Gabine cinch" or "robe" (cinctus Gabinus) or "rite" (ritus Gabinus) which tied the toga back.[94][95] This style, later said to have been part of Etruscan priestly dress,[96] was associated by the Romans with their early wars with nearby Gabii[97] and was thus used during Roman declarations of war.[98]

Materials

%252C_Olympia_Archaeological_Museum%252C_Greece_(14003830641).jpg.webp)

The traditional toga was made of wool, which was thought to possess powers to avert misfortune and the evil eye; the toga praetexta (used by magistrates, priests and freeborn youths) was always woollen.[9] Wool-working was thought a highly respectable occupation for Roman women. A traditional, high-status mater familias demonstrated her industry and frugality by placing wool-baskets, spindles and looms in the household's semi-public reception area, the atrium.[99] Augustus was particularly proud that his wife and daughter had set the best possible example to other Roman women by, allegedly, spinning and weaving his clothing.[100]

Hand-woven cloth was slow and costly to produce, and compared to simpler forms of clothing, the toga used an extravagant amount of it. To minimise waste, the smaller, old-style forms of toga may have been woven as a single, seamless, selvedged piece; the later, larger versions may have been made from several pieces sewn together; size seems to have counted for a lot.[101] More cloth signified greater wealth and usually, though not invariably, higher rank. The purple-red border of the toga praetexta was woven onto the toga using a process known as "tablet weaving"; such applied borders are a feature of Etruscan dress.[102]

Modern sources broadly agree that if made from a single piece of fabric, the toga of a high status Roman in the late Republic would have required a piece approximately 12 ft (3.7 m) in length; in the Imperial era, around 18 ft (5.5 m), a third more than its predecessor, and in the late Imperial era around 8 ft (2.4 m) wide and up to 18–20 ft (5.5–6.1 m) in length for the most complex, pleated forms.[103]

Features and styles

The toga was draped, rather than fastened, around the body, and was held in position by the weight and friction of its fabric. Supposedly, no pins or brooches were employed. The more voluminous and complex the style, the more assistance would have been required to achieve the desired effect. In classical statuary, draped togas consistently show certain features and folds, identified and named in contemporary literature.

The sinus (literally, a bay or inlet) appears in the Imperial era as a loose over-fold, slung from beneath the left arm, downwards across the chest, then upwards to the right shoulder. Early examples were slender, but later forms were much fuller; the loop hangs at knee-length, suspended there by draping over the crook of the right arm.[103]

The umbo (literally "knob") was a pouch of the toga's fabric pulled out over the balteus (the diagonal section of the toga across the chest) in imperial-era forms of the toga. Its added weight and friction would have helped (though not very effectively) secure the toga's fabric onto the left shoulder. As the toga developed, the umbo grew in size.[104]

The most complex togas appear on high-quality portrait busts and imperial reliefs of the mid-to-late Empire, probably reserved for emperors and the highest civil officials. The so-called "banded" or "stacked" toga (Latinised as toga contabulata) appeared in the late 2nd century AD and was distinguished by its broad, smooth, slab-like panels or swathes of pleated material, more or less correspondent with umbo, sinus and balteus, or applied over the same. On statuary, one swathe of fabric rises from low between the legs, and is laid over the left shoulder; another more or less follows the upper edge of the sinus; yet another follows the lower edge of a more-or-less vestigial balteus then descends to the upper shin. As in other forms, the sinus itself is hung over the crook of the right arm.[105] If its full-length representations are accurate, it would have severely constrained its wearer's movements. Dressing in a toga contabulata would have taken some time, and specialist assistance. When not in use, it required careful storage in some form of press or hanger to keep it in shape. Such inconvenient features of the later toga are confirmed by Tertullian, who preferred the pallium.[106] High-status (consular or senatorial) images from the late 4th century show a further ornate variation, known as the "Broad Eastern Toga"; it hung to the mid-calf, was heavily embroidered, and was worn over two pallium-style undergarments, one of which had full length sleeves. Its sinus was draped over the left arm.[107]

Decline

In the long term, the toga saw both a gradual transformation and decline, punctuated by attempts to retain it as an essential feature of true Romanitas. It was never a popular garment; in the late 1st century, Tacitus could disparage the urban plebs as a vulgus tunicatus ("tunic-wearing crowd").[49] Hadrian issued an edict compelling equites and senators to wear the toga in public; the edict did not mention commoners. The extension of citizenship, from around 6 million citizens under Augustus to between 40 and 60 million under the "universal citizenship" of Caracalla's Constitutio Antoniniana (212 AD), probably further reduced whatever distinctive value the toga still held for commoners, and accelerated its abandonment among their class.[66] Meanwhile, the office-holding aristocracy adopted ever more elaborate, complex, costly and impractical forms of toga.[107]

The toga nevertheless remained the formal costume of the Roman senatorial elite. A law issued by co-emperors Gratian, Valentinian II and Theodosius I in 382 AD (Codex Theodosianus 14.10.1) states that while senators in the city of Rome may wear the paenula in daily life, they must wear the toga when attending their official duties.[108] Failure to do so would result in the senator being stripped of rank and authority, and of the right to enter the Curia Julia.[109] Byzantine Greek art and portraiture show the highest functionaries of court, church and state in magnificently wrought, extravagantly exclusive court dress and priestly robes; some at least are thought to be versions of the Imperial toga.[110] In the early European kingdoms that replaced Roman government in the West, kings and aristocrats alike dressed like the late Roman generals they sought to emulate, rather than the toga-clad senators of ancient tradition.[111]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Vout 1996, p. 215 (Vout cites Servius, In Aenidem, 1.281 and Nonius, 14.867L for the former wearing of togas by women other than prostitutes and adulteresses).

- 1 2 3 Edwards 1997, pp. 81‒82.

- ↑ Virgil. Aeneid, I.282; Martial, XIV.124.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 26; Dolansky 2008, pp. 55–60.

- ↑ Swan, Peter Michael (2004). The Augustan Succession. Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-534714-2.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 28 and note 32.

- ↑ Radicke, Jan (2022). "5 praetexta – a dress of young Roman girls". Roman Women's Dress. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 355–364. doi:10.1515/9783110711554-021. ISBN 978-3-11-071155-4.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 26. Not all modern scholarship agrees that girls wore the toga praetexta; see McGinn 1998, p. 160, note 163).

- 1 2 Sebesta 2001, p. 47.

- ↑ Livy, XXVII.8,8 and XXXIII.42 (as cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities).

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 26–27 (including footnote 24), citing Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, XIX.24, 6 and Polybius, Historiae, X.4, 8.

- ↑ Flower 1996, p. 102.

- ↑ Heskel 2001, pp. 141‒142.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 26, 29; Koortbojian 2008, pp. 80–83; Dewar 2008, pp. 225–227.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 26–27; Dewar 2008, pp. 219–234.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 29; this lost work survives in fragmentary form through summary and citation by later Roman authors.

- ↑ Goldman 2001, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Rothe 2020, Chapter 2.

- ↑ Goldman 2001a, p. 217.

- ↑ Sebesta 2001, pp. 13, 222, 228, 47, note 5, citing Macrobius, 1.6.7‒13, 15‒16.

- ↑ Cleland 2013, p. 1589.

- ↑ Peruzzi 1980, p. 87, citing Artemidorus, 2.3. The usual form of Rome's Arcadian-origins myth has Argos, not Arcadia, as Temenus' ancestral home.

- ↑ Artemidorus 2020, p. 254, commentary on Artemidorus' use of tēbennos in 2.3.6.

- ↑ Peruzzi 1980, pp. 89–90; Peruzzi 1975, pp. 137–143.

- ↑ This and other problems in identification are discussed in Beard 2007, pp. 306−308 and endnotes.

- ↑ Flower 1996, p. 118: "The best model for understanding Roman sumptuary legislation is that of aristocratic self-preservation within a highly competitive society which valued overt display of prestige above all else." Sumptuary laws were intended to limit competitive displays of personal wealth in the public sphere.

- ↑ On coming of age, he also gave his protective bulla into the care of the family Lares.

- ↑ Bradley 2011, pp. 189, 194‒195; Dolansky 2008, pp. 53‒54; Sebesta 2001, p. 47.

- ↑ Olson 2008, pp. 141‒146: A minority of young girls seem to have used the praetexta, perhaps because their parents embraced the self-conscious revivalism typified in Augustan legislation and mores.

- ↑ Aubert 2014, pp. 175‒176, discussing the Lex Metilia Fullonibus Dicta of 220/217? BC, known only through its passing reference in Pliny's account of useful earths, including those employed in laundry. The best and most whitening compounds, which were also kind to coloured fabrics (such as those used in the praetextate stripe), probably cost more than ordinary Roman citizens could afford, so the togas of these status groups were laundered separately. The reasons for this law remain unclear: one scholar speculates that it was designed to protect "praetextate senators from the shame attached to the publicity of vastly unequal garb".

- ↑ Respectable women, the sons of freeborn men, and provincials during the early empire could hold lesser forms of citizenship; they were protected by law but could not vote, or stand for public office. Citizenship could be inherited, granted, up or down-graded, and removed for specific offences.

- ↑ Bispham 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ Exiles were deprived of citizenship and the protection of Roman law.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Women probably sat or stood at the very back – apart from the sacred Vestals, who had their own box at the front.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 31‒33.

- ↑ Vout 1996, p. 218ff.

- ↑ Vout 1996, p. 214.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Koortbojian 2008, pp. 77‒79. Pliny the Elder (circa 70 AD) describes togate statuary as the older, traditional form of public honour, and cuirassed statuary of famous generals as a relatively later development. An individual might hold different offices in succession, or simultaneously, each represented by a different statuary type, cuirassed as a general, and togate as a holder of state office or priest of a state cult.

- 1 2 George 2008, p. 99.

- ↑ Armstrong 2012, p. 65, citing Thorstein Veblen.

- ↑ Stone 2001, pp. 43, note 59, citing Martial, 10.74.3, 11.24.11 and 4.66.

- ↑ Vout 1996, pp. 204‒220; throughout the empire, there is evidence that old clothing was recycled, repaired and handed down the social scale, from one owner to the next, until it fell to rags. Centonarii ("patch workers") made a living by sewing clothing and other items from recycled fabric patches. The cost of a new, simple hooded cloak, using far less material than a toga, might represent three fifths of an individual's annual minimum subsistence cost: see Vout 1996, pp. 211‒212.

- ↑ Croom 2010, p. 53, citing Horace, Epodes, 4.8.

- ↑ Vout 1996, p. 209.

- ↑ Stone 2001, p. 17, citing Juvenal, Satires, 3.171‒172, Martial, 10.47.5.

- ↑ Vout 1996, pp. 205‒208: Contra Goldman's description of Roman clothing, including the toga, as "simple and elegant, practical and comfortable" in Goldman 2001, p. 217.

- 1 2 George 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Toynbee 1996, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ O'Sullivan 2011, pp. 19, 51‒58.

- ↑ Vout 1996, pp. 205‒208.

- ↑ The busts are presumed in some scholarship as marble representations of wax imagines: see Flower 1996 particularly the discussion of the Togatus Barberini ancestor busts on pp. 5‒7.

- ↑ Cash-strapped or debtor citizens with a respectable lineage might have to seek patronage from rich freedmen, who ranked as inferiors and non-citizens.

- ↑ George 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Vout 1996, p. 216.

- ↑ George 2008, pp. 101, 103–106, slaves were considered as chattels, and owed their master absolute, unconditional submission.

- ↑ A citizen's voting power was directly proportionate to his rank, status and wealth.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, p. 24; George 2008, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Armstrong 2012, p. 64: At salutationes and during any other "business times", equites were expected to wear a gold ring. Along with their toga, striped tunic and formal shoes (or calcei), this signified their status.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 24, 36‒37, citing Dio Cassius, 71.35.4 and Suetonius, Lives.

- ↑ Ceccarelli 2016, p. 33.

- ↑ Bradley 2008, p. 249, citing Quintilian.

- ↑ Dugan 2005, p. 156, note 35, citing Wyke (1994): "The Roman male citizen was defined through his body: the dignity and authority of a senator being constituted by his gait, his manner of wearing his toga, his oratorical delivery, his gestures."

- ↑ Quintilian. Institutio Oratoria, 11.3.131‒149.

- 1 2 Edmondson 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Vout 1996, pp. 214‒215, citing Aulus Gellius, 6.123–4.

- ↑ Stone 2001, p. 16: Some modern sources consider exigua as a republican type, others interpret it as poetic.

- ↑ Roller 2012, pp. 303, "transparent" toga, following Juvenal's Satire, 2, 65‒78. Juvenal's invective associates transparency with prostitute's clothing. The aristocratic divorce-and-adultery lawyer Creticus wears a "transparent" toga, which far from decently covering him, shows him for "what he really is", a cinaedus is a derogatory term for a passive homosexual.

- ↑ Rothfus 2010, p. 1, citing Appian, B. Civ., 2.17.120.

- ↑ Edmondson 2008, pp. 33, citing Suetonius, Augustus, 40.5, 44.2, and Cassius Dio, 49.16.1.

- ↑ Sebesta 2001, p. 68.

- ↑ Stone 2001, p. 39, noted 9, citing Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 8.74.195.

- ↑ Radicke, Jan (2022). "2 Varro (VPR 306) – the toga: a Primeval Unisex Garment?". Roman Women's Dress. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 578–581. doi:10.1515/9783110711554-049. ISBN 978-3-11-071155-4.

- 1 2 Radicke, Jan (2022). "6 toga – an attire of unfree prostitutes". Roman Women's Dress. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 365–374. doi:10.1515/9783110711554-022. ISBN 978-3-11-071155-4.

- ↑ Olson 2008, p. 151, note 18, citing Pliny's account of an equestrian statue to the legendary, early Republican heroine.

- ↑ Radicke, Jan (2022). "5 praetexta – a dress of young Roman girls". Roman Women's Dress. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 355–364. doi:10.1515/9783110711554-021. ISBN 978-3-11-071155-4.

- ↑ van den Berg 2012, p. 267.

- ↑ Vout 1996, pp. 205‒208, 215, citing Servius, In Aenidem, 1.281 and Nonius, 14.867L; for the former wearing of togas by women other than prostitutes and adulteresses. Some modern scholars doubt the "togate adulteress" as more than literary and social invective: cf Dixon 2014, pp. 298‒304.

- ↑ Keith 2008, pp. 197‒198; Sebesta 2001, p. 53.

- ↑ Phang 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Stone 2001, p. 13.

- 1 2 Olson 2008, p. 151, note 18.

- 1 2 Phang 2008, pp. 77‒78.

- ↑ Phang 2008, pp. 12‒17, 49‒50.

- ↑ Phang 2008, p. 112.

- ↑ Phang 2008, p. 266.

- ↑ Dugan 2005, pp. 61‒65, citing Cicero's Ad Pisonem (Against Piso).

- ↑ Rankov & Hook 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Palmer 1996, p. 83.

- ↑ Söderlind 2002, p. 370.

- ↑ Schilling 1992, p. 78.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11:4; Elliott 2006, p. 210; Winter 2001, pp. 121–123 citing as the standard source Gill 1990, pp. 245‒260; Fantham 2008, p. 159, citing Richard Oster.

- ↑ Scheid 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Scullard 1980, p. 455: "[...] the Gabine robe (cinctus Gabinus) was worn by Roman officials as a sacred vestment on certain occasions."

- ↑ Servius, note to Aeneid 7.612; Larissa Bonfante, "Ritual Dress," p. 185, and Fay Glinister, "Veiled and Unveiled: Uncovering Roman Influence in Hellenistic Italy," p. 197, both in Votives, Places, and Rituals in Etruscan Religion: Studies in Honor of Jean MacIntosh Turfa (Brill, 2009).

- ↑ Anderson, W.C.F. (1890), "Toga", Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, London: John Murray.

- ↑ Servius, note to Aeneid 7.612; see also Bonfante 2009, p. 185 and Glinister 2009, p. 197.

- ↑ In reality, she was the female equivalent of the romanticised citizen-farmer: see Hin 2014, p. 153 and Shaw 2014, pp. 195‒197.

- ↑ Culham 2014, pp. 153–154, citing Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 73.

- ↑ Sebesta 2001, pp. 43, note 59, citing Martial, 10.74.3, 11.24.11 and 4.66.

- ↑ Meyers 2016, p. 311.

- 1 2 Stone 2001, pp. 13–30.

- ↑ Métraux 2008, pp. 282–286.

- ↑ Modern reconstructions have employed applied panels of fabric, pins, and hidden stitches to achieve the effect; the underlying structure of the original remains unknown.

- ↑ Stone 2001, pp. 24–25, 38.

- 1 2 Fejfer 2008, pp. 189–194.

- ↑ Rothe 2020.

- ↑ Pharr 2001, p. 415.

- ↑ La Follette 2001, p. 58 and footnote 90.

- ↑ Wickham 2009, p. 106.

Sources

- Armstrong, David (2012). "3 Juvenalis Eques: A Dissident Voice from the Lower Tier of the Roman Elite". In Braund, Susanna; Osgood, Josiah (eds.). A Companion to Persius and Juvenal. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 59‒78. ISBN 978-1-4051-9965-0.

- Artemidorus (2020). The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by Hammond, Martin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Aubert, Jean-Jacques (2014) [2004]. "8: The Republican Economy and Roman Law: Regulation, Promotion, or Reflection?". In Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 167‒186. ISBN 978-1-107-03224-8.

- Beard, Mary (2007). The Roman Triumph. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02613-1.

- Bispham, Edward (2007). From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalization of Italy from the Social War to Augustus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923184-3.

- Bonfante, Larissa (2009). "Chapter Eleven Ritual Dress". In Gleba, Margarita; Becker, Hilary (eds.). Votives, Places, and Rituals in Etruscan Religion: Studies in Honor of Jean MacIntosh Turfa. Leiden: Brill. pp. 183‒191.

- Bradley, Keith (2008). "12 Appearing for the Defence: Apuleius on Display". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 238‒256.

- Bradley, Mark (2011). Colour and Meaning in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ceccarelli, Letizia (2016). "3 The Romanization of Etruria". In Bell, Sinclair; Carpino, Alexandra A. (eds.). A Companion to the Etruscans. Oxford and Malden: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 28–40.

- Cleland, Liza (2013). "Clothing, Greece and Rome". In Bagnall, Roger S.; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B.; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Limited. pp. 1589–1594.

- Croom, Alexandra (2010). Roman Clothing and Fashion. The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84868-977-0.

- Culham, Phyllis (2014) [2004]. "6: Women in the Roman Republic". In Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 127‒148. ISBN 978-1-107-03224-8.

- Dewar, Michael (2008). "11 Spinning the Trabea: Consular Robes and Propaganda in the Panegyrics of Claudian". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 217‒237.

- Dixon, Jessica (2014). "14. Dressing the Adulteress". In Harlow, Mary; Nosch, Marie-Louise (eds.). Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. Havertown, PA: Oxbow Books. pp. 298‒304. doi:10.2307/j.ctvh1dh8b. ISBN 9781782977155. JSTOR j.ctvh1dh8b.

- Dolansky, Fanny (2008). "2 Togam virile sumere: Coming of Age in the Roman World". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 47–70.

- Dugan, John (2005). Making a New Man: Ciceronian Self-Fashioning in the Rhetorical Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926780-4.

- Edmondson, Jonathan (2008). "1 Public Dress and Social Control in Late Republican and Early Imperial Rome". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 21–46.

- Edwards, Catharine (1997). "Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome". In Hallett, P. J.; Skinner, B. M. (eds.). Roman Sexualities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 66–95.

- Elliott, Neil (2006) [1994]. Liberating Paul: The Justice of God and the Politics of the Apostle. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2379-1.

- Fantham, Elaine (2008). "7 Covering the Head at Rome: Ritual and Gender". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Vol. 46. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 158‒171. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- Fejfer, Jane (2008). Roman Portraits in Context. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018664-2.

- Flower, Harriet I. (1996). Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press (Oxford University Press).

- George, Michele (2008). "4 The 'Dark Side' of the Toga". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Vol. 46. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 94‒112. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- Gill, David W. J. (1990). "The Importance of Roman Portraiture for Head-Coverings in 1 Corinthians 11:2–16" (PDF). Tyndale Bulletin. 41 (2): 245–260. doi:10.53751/001c.30525. S2CID 163516649.

- Glinister, Fay (2009). "Chapter Twelve Veiled and Unveiled: Uncovering Roman Influence in Hellenistic Italy". In Gleba, Margarita; Becker, Hilary (eds.). Votives, Places, and Rituals in Etruscan Religion: Studies in Honor of Jean MacIntosh Turfa. Leiden: Brill. pp. 193‒215.

- Goldman, Bernard (2001). "10 Graeco-Roman Dress in Syro-Mesopotamia". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 163–181.

- Goldman, Norma (2001a). "13 Reconstructing Roman Clothing". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 213–240.

- Heskel, Julia (2001). "7 Cicero as Evidence for Attitudes to Dress in the Late Republic". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 133–145.

- Hin, Saskia (2014) [2004]. "7: Population". In Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 149‒166. ISBN 978-1-107-03224-8.

- Keith, Alison (2008). "9 Sartorial Elegance and Poetic Finesse in the Sulpician Corpus". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Vol. 46. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 192‒202. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- Koortbojian, Michael (2008). "3 The Double Identity of Roman Portrait Statues: Costumes and Their Symbolism at Rome". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 71‒93.

- La Follette, Laetitia (2001). "3 The Costume of the Roman Bride". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 54–64. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- McGinn, Thomas A. J. (1998). Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Métraux, Guy P. R. (2008). "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Vol. 46. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 271–294. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- Meyers, Gretchen E. (2016). "21 Tanaquil: The Conception and Construction of an Etruscan Matron". In Bell, Sinclair; Carpino, Alexandra A. (eds.). A Companion to the Etruscans. Oxford and Malden: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 305–320.

- Olson, Kelly (2008). "6 The Appearance of the Young Roman Girl". In Edmondson, Johnathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Vol. 46. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 139‒157. doi:10.3138/9781442689039. ISBN 9781442689039. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442689039.

- O'Sullivan, Timothy M. (2011). Walking in Roman Culture. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00096-4.

- Palmer, Robert E. A. (1996). "The Deconstruction of Mommsen on Festus 462/464 L, or the Hazards of Interpretation". In Linderski, Jerzy (ed.). Imperium Sine Fine: T. Robert S. Broughton and the Roman Republic. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner. pp. 75–102. ISBN 9783515069489.

- Peruzzi, Emilio (1975). "Τήβεννα". Euphrosyne. 7: 137–143. doi:10.1484/J.EUPHR.5.127070.

- Peruzzi, Emilio (1980). Mycenaeans in Early Latium. Rome: Edizioni dell'Ateneo & Bizzarri.

- Phang, Sara Elise (2008). Roman Military Service: Ideologies of Discipline in the Late Republic and Early Principate. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88269-9.

- Pharr, Clyde (2001). The Theodosian Code and Novels and the Sirmondian Constitutions. Union, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-146-3.

- Radicke, Jan (2022). Roman Women's Dress, Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-071155-4

- Rankov, Boris; Hook, Richard (1994). The Praetorian Guard. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-855-32361-2.

- Roller, Matthew (2012). "13 Politics and Invective in Persius and Juvenal". In Braund, Susanna; Osgood, Josiah (eds.). A Companion to Persius and Juvenal. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 283‒311. ISBN 978-1-4051-9965-0.

- Rothe, Ursula (2020). The Toga and Roman Identity. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4725-7154-0.

- Rothfus, Melissa A. (2010). "The Gens Togata: Changing Styles and Changing Identities" (PDF). American Journal of Philology. 131 (3): 425‒452. doi:10.1353/ajp.2010.0009. S2CID 55972174.

- Sebesta, Judith Lynn (2001). "2 Symbolism in the Costume of the Roman Woman". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 46–53.

- Schilling, Robert (1992) [1991]. "Roman Sacrifice". In Bonnefoy, Yves; Doniger, Wendy (eds.). Roman and European Mythologies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 77‒81. ISBN 0-226-06455-7.

- Scheid, John (2003). An Introduction to Roman Religion. Translated by Lloyd, Janet. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34377-1.

- Scullard, Howard Hayes (1980) [1935]. A History of the Roman World: 753 to 146 BC (Fourth ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30504-7.

- Shaw, Brent D. (2014) [2004]. "9: The Great Transformation: Slavery and the Free Republic". In Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 187‒212. ISBN 978-1-107-03224-8.

- Söderlind, Martin (2002). Late Etruscan Votive Heads from Tessennano: Production, Distribution, Socio-Historical Context. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-8-882-65186-2.

- Stone, Shelley (2001). "1 The Toga: From National to Ceremonial Costume". In Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 13–45.

- Toynbee, J. M. C. (1996) [1971]. Death and Burial in the Roman World. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-85507-8.

- van den Berg, Christopher S. (2012). "12 Imperial Satire and Rhetoric". In Braund, Susanna; Osgood, Josiah (eds.). A Companion to Persius and Juvenal. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 262‒282. ISBN 978-1-4051-9965-0.

- Vout, Caroline (1996). "The Myth of the Toga: Understanding the History of Roman Dress". Greece & Rome. 43 (2): 204–220. doi:10.1093/gr/43.2.204. JSTOR 643096.

- Wickham, Chris (2009). The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000. London and New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0.

- Winter, Bruce W. (2001). After Paul Left Corinth: The Influence of Secular Ethics and Social Change. Grand Rapids, WI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-802-84898-2.