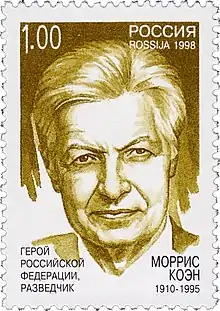

Morris Cohen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 2, 1910[1] Harlem, New York City, U.S.[1] |

| Died | June 23, 1995 (aged 84)[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Mississippi State University Columbia University |

| Spouse | Lona Cohen |

| Awards | Order of the Red Banner, Order of Friendship of Nations, Hero of the Russian Federation[1] |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | USSR |

| Service years | 1939–1961 (arrest) |

| Codename | Peter Kroger (while in the UK) |

Morris Cohen (Russian: Моррис Генрихович Коэн, Morris Genrikhovich Koen; July 2, 1910 – June 23, 1995), also known by his alias Peter Kroger, was an American convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union. His wife Lona was also an agent.[2] They became spies because of their communist beliefs.

Early life and education

Morris Cohen was born in Harlem, New York City, on July 2, 1910, to a Jewish immigrant family. His father had immigrated from an area near Kyiv in present-day Ukraine. His mother was from Vilnius in present-day Lithuania; the couple had met and married in New York.[1] Cohen was a football standout at James Monroe High School in the Bronx. After briefly attending New York University he was awarded an athletic scholarship to Mississippi A&M College (now Mississippi State University). He was injured in a freshman game. No longer able to play football, he was kept on scholarship as athletic manager. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in business, and after a year of graduate work transferred to the University of Illinois. There he was active in agitprop work for the National Student League, a communist organisation. He was declared persona non grata after one semester and returned to the Bronx, where he became a full member and organizer for the American Communist Party. After World War II, he received a master's degree in education from Columbia University.[3]

Career

International Brigades

In 1937, Cohen joined the Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion and fought as a foreign national volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, as did others who were sympathetic to the anti-Franco movement. He met Amadeo Sabatini, a career Soviet spy who recruited him. After being injured, in November 1938 Cohen returned to the United States. He began serving Soviet foreign intelligence.[1]

Soviet espionage

In mid-1942, Cohen was drafted into the U.S. Army and served in Europe. He was discharged from the Army in November 1945 and returned to the United States where he resumed his espionage work for the Soviet Union.[1]

Among other things, the Cohens delivered detailed blueprints on the nuclear bomb to Moscow in 1945.[2]

As Soviet spy networks were compromised in this period, connection with Soviet intelligence was temporarily ended, but resumed in 1948, when the Rezidentura ascertained that Cohen could be approached. Together with Lona Cohen, they ensured the continued secret connection with a number of the most valuable sources of the Rezidentura. They began working with Col. Rudolf Abel up to 1950, when they secretly left the United States and moved to Lublin, Poland. While in Poland, Morris and Lona engaged in numerous foreign missions for the Soviet Union, traveling to Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands.[3]

In 1954, the Cohens moved to 45 Cranley Drive in Ruislip, London where they had numerous pieces of hidden equipment for espionage, and an antenna looping around their attic, used for their transmissions to Moscow. Their cover was as antiquarian book dealers under the names of Peter and Helen Kroger working with KGB agent Konon Molody who used the cover name Gordon Lonsdale.[1]

Arrest and trial

British security officials arrested the Cohens on January 7, 1961, for their part in a Soviet espionage network known as the Portland Spy Ring that had penetrated the Royal Navy. They were convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Morris and Lona served eight years in prison, because they were subjects of a prisoner exchange.[1]

Files released by the National Archives in September 2019 indicated that MI5 had found "espionage equipment hidden inside an oversized Ronson cigarette lighter" in a bank safety deposit box according to The Times; this became the breakthrough required to close down the spy ring.[4]

Prisoner exchange

In 1967, the Soviet Union admitted that the Cohens were spies. In July 1969, Britain exchanged them for Gerald Brooke, a British subject held in the Soviet Union,[5] as well as Michael Parsons and Mr. Anthony Lorraine, the British subjects who in 1968 were sentenced by Soviet courts for smuggling drugs into the Soviet Union.[6] Both the United States and the UK had conducted such exchanges before, such as Soviet spy Rudolf Abel for U2 pilot Gary Powers, and Konon Molody for Greville Wynne in 1964. But In this case, the opposition criticised Harold Wilson's Labour Government for agreeing to release dangerous Soviet agents, such as the Krogers (i.e., the Cohens), in exchange for Brooke, described as a propagandist. Opponents claimed that it set a dangerous precedent and was an example of blackmail rather than a fair exchange.[1]

Moscow

The Cohens lived in Moscow, where Morris trained spies for the Soviets. He and Lona were later given pensions by the KGB, and remained in the city for the remainder of their lives.[1]

Personal life and death

In 1941, Cohen married Lona, a Communist Party activist. She later became a spy and courier for Manhattan Project physicist Theodore Hall. They were part of a ring of atomic spies who were later revealed to have been far more damaging to US interests than the Rosenberg ring.

During some period, Cohen was an employee of Amtorg.[7]

After training Soviet agents in Moscow for decades, Cohen retired on a pension, as did his wife. He died in Moscow on June 23, 1995. Lona had died in 1992.[2]

Awards

The Cohens were awarded the Order of the Red Banner and the Order of Friendship of Nations by the Soviet Union for their espionage work. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, they also were given the title of Hero of the Russian Federation by the Yeltsin government.

Venona

The Cohens are referenced in Venona decrypts 1239 KGB New York to Moscow, August 30, 1944; 50 KGB New York to Moscow, January 11, 1945, regarding an erroneous report that Morris Cohen had been killed in Europe. The Cohens helped pass Manhattan Project secrets to the Soviet Union. His code name in Soviet intelligence and the Venona files is "Volunteer".

Representation in other media

British playwright Hugh Whitemore dramatized the case as Pack of Lies, which was performed in London's West End, starring Judi Dench and Michael Williams. The play was produced on Broadway for 3½ months in 1985, with Rosemary Harris starring; she won the best actress Tony award for her portrayal of a British neighbor of the Cohens/Krogers.

The play was adapted as a TV movie starring Ellen Burstyn, Alan Bates, Teri Garr and Daniel Benzali (as "Peter Schaefer," i.e., "Peter Kroger"/ Morris Cohen) which aired in the U.S. on CBS in 1987. The plot centered on the neighbors (and seeming friends), whose house was used as a base from which the British security services could spy on the Cohens. It explored the way that paranoia, suspicion and betrayal gradually destroyed their lives during that time.

Helene Hanff in her book, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street (1973), refers to the Cohens’ cover as antiquarian book dealers Peter and Helen Kroger. Under those identities, they were friends of London book dealer Frank Doel. Based on her long-term friendship with Doel, mostly via letters, she had earlier written and published 84 Charing Cross Road (1970), which was a bestseller. O. F. (Oswald Frederick) Snelling, who worked as a auctioneer clerk at Hodgson's in 1949, later Sotheby's Rare Book Department, writes extensively about his friendship with Peter and Helen Kroger in his book Rare Books and Rarer People. After the arrest of Peter and Helen Kroger, Snelling volunteered to wind up Peter Kroger’s business, auctioning the remaining books. Snelling also tells about his contacts with KGB agent Konon Molody who used the cover name Gordon Lonsdale.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Моррис Коэн. svr.gov.ru

- 1 2 3 "Morris Cohen, 84, Soviet Spy Who Passed Atom Plans in 40's". The New York Times. July 5, 1995. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

Morris Cohen, an American who spied for the Soviet Union and was instrumental in relaying atomic bomb secrets to the Kremlin in the 1940s, has died, Russian newspapers reported today. Mr. Cohen, best known in the West as Peter Kroger, died of heart failure in a Moscow hospital on June 23 at age 84, according to news reports.

- 1 2 Carr, Barnes (2016) Operation Whisper: The Capture of Soviet Spies Morris and Lona Cohen. Lebanon NH: The University Press of New England. pp. 200–206. ISBN 9781611688092

- ↑ "Portland spies undone by a giant lighter". The Times. September 24, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

Between 1956 and 1961 secrets extracted from the Portland Underwater Detection Establishment enabled the Soviet Union to construct a quieter submarine class.

- ↑ BBC (July 24, 1969). "On This Day: 24 July 1969: Briton freed from Soviet prison".

- ↑ MR. GERALD BROOKE (RELEASE)

- ↑ "Red Files: Amtorg". PBS. 1999. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

Further reading

- Albright, Joseph; Kunstel, Marcia (1997). Bombshell: The Secret Story of America's Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy. New York: Times Books. pp. 244–253. ISBN 9780812928617.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (1999). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 316, 317–319, 320, 321, 334. ISBN 0-300-08462-5.

- Russian Federal Foreign Intelligence Service (1995). Veterany vneshnei razvedki Rosii (Veterans of Russian foreign intelligence service). Moscow: Russian Federal Foreign Intelligence Service.

- Trahair, Richard C.S.; Miller, Robert (2009). Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-75-9.

- West, Rebecca (1964). The New Meaning of Treason. New York: Viking. pp. 281–288.

- Recollections of Ruislip neighbors: http://www.ruislip.co.uk/kroger/kroger.htm

External links

- BBC (March 13, 1961). "On This Day: 13 March 1961: Five Britons accused of spying for Moscow". Includes a video news report on the Krogers/Cohens' return to the Soviet Union and an interview with former Foreign Secretary George Brown over the issues.

- Chervonnaya, Svetlana. "Red Files: Secret Victories of the KGB – Svetlana Chervonnaya Interview". PBS.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Subject: Morris and Lona Cohen, File Number: 100-406659".

- Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) (in Russian)