| Mount Timpanogos | |

|---|---|

Mt. Timpanogos from Provo | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 11,753 ft (3,582 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 5,269 ft (1,606 m)[1] |

| Listing |

|

| Coordinates | 40°23′27″N 111°38′45″W / 40.390838842°N 111.645947125°W[2] |

| Geography | |

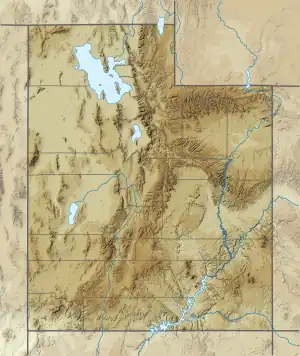

Mount Timpanogos Location in Utah | |

| Location | Utah County, Utah, U.S. |

| Parent range | Wasatch Range |

| Topo map | USGS Timpanogos |

Mount Timpanogos, often referred to as Timp, is the second-highest mountain in Utah's Wasatch Range. Timpanogos rises to an elevation of 11,752 ft (3,582 m) above sea level in the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest. With 5,270 ft (1,610 m) of topographic prominence, Timpanogos is the 47th-most prominent mountain in the contiguous United States.[3]

The mountain towers about 7,000 ft (2,100 m) over Utah Valley, including the cities of Lehi, Provo, Orem, Pleasant Grove, American Fork, Lindon and others. The exposed massif of the mountain is made up entirely of limestone and dolomite from the Pennsylvanian period, and is about 300 million years old. Heavy winter snowfall is characteristic of this portion of the Wasatch Range, and avalanche activity is common in winter and spring. The mountain is also home to Timpanogos Cave National Monument, a series of decorated caves in the north end of the mountain that have guided ranger tours open daily to the public during the warmer months.

Etymology

The word Timpanogos comes from the Timpanogos tribe who lived in the surrounding valleys from AD 1400. The name translates as "rock" (tumpi-), and "water mouth" or "canyon" (panogos).[4]

Glacial activity

.jpg.webp)

Mount Timpanogos displays many examples of various glacial processes and the sculpting power of moving ice. Ice Age glaciers mantled the peak until relatively recently and dramatically shaped the mountain into an Alpine tableau of knife-edge ridges and yawning, U-shaped amphitheaters. A remnant of these glaciers persists in the deeply recessed hanging valley below the main summit. Timpanogos Glacier is a rock-covered mass found on a long, north-facing slope and usually has patches of snow the entire year. Although an above-ground cirque glacier was present before the Dust Bowl Drought of the 1930s, no glacial ice is visible today. However, in 1994, a large crevasse opened up, revealing that there still is a glacier buried beneath the talus. Flowing water can occasionally be heard beneath the rocks. Emerald Lake, a small proglacial lake at the bottom of the cirque, often exhibits a blue color, indicating that the glacier is probably still moving, although perhaps too slowly to be noticeable. The locally unique ice is a relic of the region's formerly colder climate and has long been a major attraction to hikers and climbers on the mountain, who often slide down its permanent snowfield as a shorter descent route. Its precise classification remains the subject of ongoing debate, whether "real" or not.[5]

Hiking

Mount Timpanogos is one of Utah's most popular hiking/climbing destinations and is climbed year-round. Winter climbing requires advanced mountaineering ability. In spring, undercutting of deeply drifted snow by streams creates a hazard that has proven fatal on several occasions.[6] Climbers can fall through the undermined snow 50 feet (15 m) or more into the icy stream underneath.

Although it is a 14-mile (23 km) round-trip hike, with almost 5,300 feet (1,600 m) of elevation gain, Timpangos's summit is one of the most frequently visited in the Rocky Mountains. There are two main trails to the top: the first starts at Aspen Grove with a trailhead elevation of 6,910 feet (2,106 m), and the second starts at the Timpooneke campground in American Fork Canyon at 7,370 feet (2,250 meters). The two trails are nearly the same length. Hikers on the trails climb through montane forest, subalpine and alpine zones. The hike is marked by waterfalls, conifers, rocky slopes and ridges, mountain goats, and a small lake, Emerald Lake, at 10,380 feet (3,160 m). A short diversion will lead hikers past a World War II bomber crash site. Other climbing routes exist on the mountain, but they are more technically demanding and require special skills and mountaineering gear.

Prior to 1970, an annual Provo event called the "Timp Hike" sent thousands of people up the mountain's slopes. From 1911 to 1970 this one-day event (which took place generally on the third or fourth weekend in July) attracted thousands of people to the mountain. It also created the need for infrastructure, such as the stone shelter built in 1959 near Emerald Lake and a smaller metal shack on the summit (this was used as an observation deck complete with brass rods etched with notches aligned with various landmarks). The hike caused environmental damage to the mountain, and was finally canceled to help preserve the delicate mountain ecosystem. Despite the presence of the existing structures, the mountain was designated a wilderness area by the U.S. Congress in 1984.

Geology

The rock which forms the visible surface of Mount Timpanogos is primarily limestone composed of compacted sediment laid down onto an ancient seafloor over millions of years during the late Carboniferous Period (roughly 300 million years ago).[7][8] Older rock exists beneath the limestone on the surface. The limestone was subsequently lifted high above sea level and the mountain itself became prominent as the Western valley sunk due to basin and range faulting.[9] The most contemporary features of the mountain were formed through recent glacial and water erosion.

Climate

| Climate data for Mount Timpanogos 40.3856 N, 111.6428 W, Elevation: 11,060 ft (3,370 m) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 26.8 (−2.9) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

36.5 (2.5) |

46.3 (7.9) |

58.8 (14.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

66.0 (18.9) |

57.2 (14.0) |

44.4 (6.9) |

32.8 (0.4) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

43.4 (6.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 17.3 (−8.2) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

20.7 (−6.3) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

34.7 (1.5) |

46.0 (7.8) |

54.5 (12.5) |

52.9 (11.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

33.3 (0.7) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

17.0 (−8.3) |

32.2 (0.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 7.9 (−13.4) |

6.1 (−14.4) |

10.0 (−12.2) |

14.1 (−9.9) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

33.2 (0.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

39.9 (4.4) |

32.1 (0.1) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

13.9 (−10.1) |

7.8 (−13.4) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 7.50 (191) |

5.77 (147) |

5.75 (146) |

4.23 (107) |

4.24 (108) |

2.05 (52) |

1.16 (29) |

1.99 (51) |

3.38 (86) |

4.05 (103) |

4.53 (115) |

6.45 (164) |

51.1 (1,299) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[10] | |||||||||||||

Hazards

Since 1982 the Timpanogos Emergency Response Team ("TERT") has been established on the mountain on weekends to provide first aid, rescue and communication.[11]

The Timpanogos Glacier is one of the major sources of injury or death to hikers on Timpanogos, particularly when some attempt to "glissade" (or slide rapidly) down the snowfield's surface with the assistance of a shovel or other device to save time descending. There have been many cases of injuries from buried rocks under the snow as well. There have been numerous life flight rescues on the mountain, often caused by this activity. The frequency of these rescues, however, greatly diminished once TERT was established.

Folklore

In the early 1900s Eugene Lusk "Timp" Roberts, a professor at Brigham Young University, initiated an annual hike and pageant intended to "sell Timpanogos to the world."[12] One way was to craft his take on native people's folklore.[4] Some observers believe the ridgeline of Mount Timpanogos superficially resembles a sleeping woman. Roberts wrote his folk tale of the maiden Utahna and her sacrifice to her gods with this as the launch point, with one version the basis for a ballet.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Mount Timpanogos, Utah". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ "Timpanogos". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ "USA Lower 48 Peaks with 5000 feet of Prominence". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- 1 2 "The Legend of Timpanogos". Timpanogos Cave National Monument. National Park Service. February 24, 2015. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "100 Years on the Timpanogos Glacier". SummitPost.org. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ Kelsey, Michael: Climbing and Exploring Utah's Mount Timpanogos; Provo, Utah, Kelsey Publishing, 1989, p. 203

- ↑ Carter, Edward L. (August 18, 1996). "Mountain Mystique: Majestic Timpanogos Casts A Magical Spell With Its Lofty Peaks And Folklore". Deseret News.

- ↑ Hintze, L.F., 1980, Geologic map of Utah: Utah Geological and Mineral Survey

- ↑ "The Wasatch Fault" (PDF). Utah Geological Survey. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

To find the table data on the PRISM website, start by clicking Coordinates (under Location); copy Latitude and Longitude figures from top of table; click Zoom to location; click Precipitation, Minimum temp, Mean temp, Maximum temp; click 30-year normals, 1991-2020; click 800m; click Retrieve Time Series button.

- ↑ Timpanogos Emergency Response Team website

- ↑ Carter, Edward L. "Timp Roberts". BYU Magazine. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ Madson, Scott (2 Apr 2004). "Timpanogos legend comes to stage". The Daily Universe. Brigham Young University. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

External links

- A Biotic Study of Mount Timpanogos by Vasco M. Tanner, MSS 8552 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Summitpost page for Mount Timpanogos - hiking and climbing routes, history, etc.

- Hiking Mount Timpanogos Safely page - information on hiking the summit routes safely, maps, etc.