| 1970s in music in the UK |

| Events |

|---|

Popular music of the United Kingdom in the 1970s built upon the new forms of music developed from blues rock towards the end of the 1960s, including folk rock and psychedelic rock movements. Several important and influential subgenres were created in Britain in this period, by pursuing the limitations of rock music, including British folk rock and glam rock,[1] a process that reached its apogee in the development of progressive rock and one of the most enduring subgenres in heavy metal music. Britain also began to be increasingly influenced by third world music (roots of World music), including Jamaican and Indian music, resulting in new music scenes and subgenres. In the middle years of the decade the influence of the pub rock and American punk rock movements led to the British intensification of punk, which swept away much of the existing landscape of popular music, replacing it with much more diverse new wave[2] and post punk bands who mixed different forms of music and influences to dominate rock and pop music into the 1980s.

Rock

Progressive rock

Progressive or 'prog rock' developed out of late 1960s blues-rock and psychedelic rock. Dominated by British bands it was part of an attempt to elevate rock music to new levels of artistic credibility.[3] Progressive rock bands attempted to push the technical and compositional boundaries of rock by going beyond the standard verse-chorus-based song structures. The arrangements often incorporated elements drawn from classical, jazz, and world music. Instrumentals were common, while songs with lyrics were sometimes conceptual, abstract, or based in fantasy. Progressive rock bands sometimes used "concept albums that made unified statements, usually telling an epic story or tackling a grand overarching theme."[3] King Crimson have been seen as the band who established the concept of progressive rock". The term was applied to the music of bands and artists such as Yes, Genesis, Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Kate Bush, Soft Machine, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer.[3] It reached its peak of popularity in the mid-1970s, but had mixed critical acclaim and the punk movement can be seen as a reaction against its musicality and perceived pomposity.

British rock mainstream

.jpg.webp)

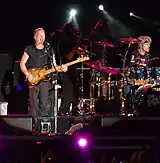

Some British rock bands that began their careers in the British Invasion 60s, notably The Rolling Stones, The Who and The Kinks, also developed their own particular styles and expanded their international fan base during 1970s, but would be joined by new acts in new styles and subgenres.[4]

UK mainstream rock was often derived from folk rock, using acoustic instruments and putting more emphasis on melody and harmonies.[5] It reached its peak in the mid- to late 1970s with acts like the reformed Fleetwood Mac, whose Rumours (1977) was the best selling album of the decade.[6] Major British soft rock artists of the 1970s included 10cc, Mungo Jerry and ELO. A large number of mainstream rock songs fit into the singer-songwriter classification. Some of the actives were Cat Stevens, Steve Winwood and Elton John.[7] Kate Bush became the first solo woman to have a self-written song become a number 1 UK single and became a sensation, drawing on art rock, literature, dance and mime.[8][9]

Hard rock and Heavy metal

The hard rock and heavy metal genres were developed from blues-rock in the late 1960s and early 1970s, largely in England and the United States.[10] Played louder and with more intensity, it often emphasised the electric guitar, both as a rhythm instrument using simple repetitive riffs and as a solo lead instrument, and was more likely to be used with distortion and other effects.[11] Key acts included British Invasion bands like The Who and The Kinks, as well as psychedelic era performers like Cream, Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Jeff Beck Group.[11] Adopting a form of boogie rock, Status Quo became one of the UK's leading rock bands throughout the rest of the 1970s.[12]

From the late 1960s the term heavy metal began to be used to describe some hard rock played with even more volume and intensity.[13] By 1970 three key British bands had developed the characteristic sounds and styles which would help shape the subgenre. Led Zeppelin added elements of fantasy to their riff laden blues-rock, Deep Purple brought in symphonic and medieval interests from their progressive rock phase and Black Sabbath introduced facets of the gothic and modal harmony, helping to produce a "darker" sound.[14] These elements were taken up by a "second generation" of heavy metal bands into the late 1970s. Rainbow helped turn the genre into a form of arena rock; Judas Priest helped spur the genre's evolution by discarding much of its blues influence and Motörhead introduced a punk rock sensibility and an increasing emphasis on speed. Bands in the new wave of British heavy metal, such as Iron Maiden and Saxon, followed in a similar vein. Unlike progressive rock, heavy metal (already a minority sub-culture) was able to survive the rise of punk and electronic music intact. Despite a lack of airplay and very little presence on the singles charts, late-1970s heavy metal built a considerable following, particularly among adolescent working-class males in North America and Europe.[15]

Glam rock

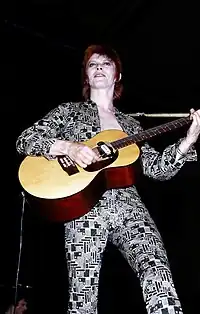

Glam or glitter rock was developed in the UK in the post-hippie early 1970s. It was characterised by outrageous clothes, makeup, hairstyles, and platform-soled boots.[16] The flamboyant lyrics, costumes, and visual styles of glam performers were a campy, playing with categories of sexuality in a theatrical blend of nostalgic references to science fiction and old movies, all over a guitar-driven hard rock sound.[1] Pioneers of the genre included Marc Bolan and T.Rex, David Bowie, Roxy Music, Mott the Hoople.[1] These, and many other acts straddled the divide between pop and rock music, managing to maintain a level of respectability with rock audiences, while enjoying success in the singles chart, including Queen and Elton John. Other performers aimed much more directly for the popular music market, where they were the dominant groups of their era, including Slade and Sweet.[1] The glitter image was pushed to its limits by Gary Glitter and The Glitter Band. Largely confined to the British, glam rock peaked during the mid-1970s, before it disappeared in the face of punk rock and new wave trends.[1]

British folk rock

British folk rock was developed in Britain during the mid to late 1960s by the bands Fairport Convention, and Pentangle which built on elements of American folk rock, and on the second British folk revival.[17] Rather than mixing electric music with forms of American influenced progressive folk, it used traditional English music as its basis.[18] A significant moment was the release of Fairport Convention's 1969 album Liege & Lief, which developed further in the 1970s, when it was taken up by groups such as Pentangle, Steeleye Span and the Albion Band.[18] It was rapidly adopted and developed in the surrounding Celtic cultures of Brittany, where it was pioneered by Alan Stivell and bands like Malicorne; in Ireland by groups such as Horslips; and also in Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man and Cornwall, to produce Celtic rock and its derivatives.[19] It was also influential in those parts of the world with close cultural connections to Britain, such as the US and Canada and gave rise to the subgenre of Medieval folk rock and the fusion genres of folk punk and folk metal.[18] By the end of the 1970s the genre was in steep decline in popularity, as other forms of music, including punk and electronic began to be established.[18]

Pub rock

Pub rock was a short-lived trend that left a lasting influence on the British music scene, especially in punk rock. It was a back-to-basics movement that reacted against the glittery glam rock of David Bowie and Gary Glitter, and peaked in the mid-1970s. Pub rock developed in large north London pubs.[20] and is said to have begun in May 1971 with Eggs over Easy, an American band, playing in the Tally Ho! in Kentish Town. A group of musicians who had been playing in blues and R&B bands during the 1960s and early 70s soon formed influential bands like Brinsley Schwarz, Ducks Deluxe. Brinsley Schwarz was probably the most influential group, achieving some mainstream success both in the UK and in the States.[21] The second wave of pub rock included Kilburn and the High Roads, Ace and Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers; these were followed by the third and final wave of pub rock, including Dr. Feelgood, Eddie and the Hot Rods, Ian Dury, Nick Lowe and Sniff 'n' the Tears. Several pub rock musicians joined the new wave acts such as Graham Parker's backing band, The Rumour, Elvis Costello & the Attractions and even The Clash.[22]

Punk rock

Punk rock developed between 1974 and 1976, originally in the United States, where it was rooted in garage rock, and other forms of what is now known as protopunk music.[23] This was taken up in Britain by bands also influenced by the pub rock scene and US punk rock, like the Sex Pistols and The Clash, The Damned, The Jam, The Stranglers, Generation X, The Buzzcocks, Sham 69, Siouxsie and the Banshees and the Tom Robinson Band, who became the vanguard of a new musical and cultural movement, blending simple aggressive sounds and lyrics with clothing styles and a variety of anti-authoritarian ideologies.[24] Punk rock bands eschewed the perceived excesses of mainstream 1970s rock, creating fast, hard-edged music, typically with short songs, stripped-down instrumentation, and often political, anti-establishment lyrics.[24] Punk embraced a DIY (do it yourself) ethic, with many bands self-producing their recordings and distributing them through informal channels.[24] 1977 saw punk rock spreading around the world, and it became a major international cultural phenomenon. However, by 1978, the initial impulse had subsided and punk had morphed into the wider and more diverse new wave and post punk movements.[24]

Post punk

During the second half of the 1970s and early 1980s musicians identifying with or inspired by Punk rock also pursued a broad range of other variations, giving rise among others to the post-punk movement. The genre retained its roots in the punk movement but was more introverted, complex and experimental.[25] Post-punk laid the groundwork for alternative rock by broadening the range of punk and underground music, incorporating elements of Krautrock (particularly the use of synthesisers and extensive repetition), Jamaican dub music (specifically in bass guitar), American funk, studio experimentation, and even punk's traditional polar opposite, disco, into the genre.

During 1976–77, in the midst of the original UK punk movement, bands emerged such as Manchester's Joy Division, The Fall, and Magazine, Leeds' Gang of Four, and London's The Raincoats that became central post-punk figures. Some bands classified as post-punk, such as Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, had been active well before the punk scene coalesced;[26] others, such as The Slits and Siouxsie and the Banshees, transitioned from punk rock into post-punk.

New wave

As the initial punk impulse began to subside, with the major punk bands either disbanding or taking on new influences, the term new wave began to be used to describe particularly British bands that emerged in the later 1970s with mainstream appeal. These included pop bands like XTC, Squeeze and Nick Lowe, the electronic rock of Gary Numan as well as songwriters like Elvis Costello, rock & roll influenced bands like the Pretenders, the reggae influenced music of bands like The Police, as well as bands of the ska revival like The Specials, The Beat, and Madness.[2] By the end of the decade many of these bands, most obviously the Police, were beginning to make an impact in American and world markets.[27] Significant popular British New Wave acts at the end of the decade included The Boomtown Rats, Ian Dury and the Blockheads, and Lene Lovich.[28]

Synth rock

Many progressive rock bands had incorporated synthesisers into their sound, including Pink Floyd, Yes and Genesis.[29] In 1977 Ultravox member Warren Cann purchased a Roland TR-77 drum machine, which was first featured in their October 1977 single release "Hiroshima Mon Amour".[30] The ballad arrangement, metronome-like percussion and heavy use of the ARP Odyssey synthesiser was effectively a prototype for nearly all synth pop and rock bands that were to follow. In 1978, the first incarnation of The Human League released their début single "Being Boiled". Others were soon to follow, including Tubeway Army, a little-known outfit from West London, who dropped their punk rock image and jumped on the band wagon, topping the UK charts in the summer of 1979 with the single "Are Friends Electric?". This prompted the singer, Gary Numan to go solo and in the same year he release the Kraftwerk inspired album, The Pleasure Principle and again topped the charts for the second time with the single "Cars".[31] Particularly through its adoption by New Romantics, synthesisers came to dominate the pop and rock music of the early 80s. Albums such as Visage's Visage (1980), John Foxx's Metamatic (1980), Gary Numan's Telekon (1980), Ultravox's Vienna (1980), The Human League's Dare (1981) and Depeche Mode's Speak & Spell (1981), established a sound that influenced most mainstream pop and rock bands, until it began to fall from popularity in the mid-1980s.[32]

Pop

The early 1970s were probably the decade when British pop music was most dependent on the group format, with pop acts, like rock bands, playing guitars and drums, with occasional additions of keyboard or orchestration. Some of these groups were in some sense "manufactured", but many were competent musicians, playing on their own recordings and writing their own material. In addition to the glam and glitter rock bands who enjoyed considerable success in the early 1970s. Aiming much more for the teen market, partly in response to US pop groups were The Rubettes and The Bay City Rollers.[33] Largely vocal-based groups included the New Seekers, Brotherhood of Man, the last of these designed as a British answer to ABBA.[34] Individuals who enjoyed successful pop careers in this period included Gilbert O'Sullivan, David Essex, Leo Sayer, Rod Stewart and Elton John.[28] In addition there were the rock and roll revivalists Mud, Showaddywaddy and Alvin Stardust.[35] This pattern changed radically in the late 1970s as a result of the impact of punk rock.

Folk music

Perhaps the finest individual work in the genre was from artists early 1970s artists like Nick Drake, and John Martyn, but these can also be considered the first among the British 'folk troubadours' or 'singer-songwriters', individual performers who remained largely acoustic, but who relied mostly on their own individual compositions.[36] The most successful of these was Ralph McTell, whose ‘Streets of London’ reached number 2 in the UK Single Charts in 1974, and whose music is clearly folk, but without and much reliance on tradition, virtuosity, or much evidence of attempts at fusion with other genres.[37]

British soul/jazz

Carl Douglas got #1 hits "Kung Fu Fighting" (1974), and Biddu Orchestra records also appeared in the charts.[38] "Kung Fu Fighting" in particular sold eleven million records worldwide.[39] Popularity of British jazz from the 1950s, 1960s with Kenny Ball and Chris Barbar, UK jazz continued with innovative music scene. Some of the technical musicians during this period include guitarist John McLaughlin and Dave Holland (both of whom joined Miles Davis's group), pianists Keith Tippett and John Taylor, saxophonists Evan Parker, Mike Osborne, and the Canadian-born trumpeter Kenny Wheeler who had settled in Britain.[40][41] In the 1970s a notable development was the creation of various British jazz rock bands like Soft Machine, Nucleus, Colosseum, Henry Cow(avant garde band), National Health and Ginger Baker's Air Force, making it a major influence on progressive rock music.[42]

Industrial music

Industrial music was an experimental music style, often including electronic music, that drew on transgressive and provocative themes. The term was coined in the mid-1970s to describe Industrial Records artists. It blended avant-garde electronics experiments (including tape music, musique concrète, white noise, synthesisers, sequencers) and a punk sensibility.[43] The first industrial artists experimented with noise and controversial topics. Their production was not limited to music, but included mail art, performance art, installation pieces and other art forms.[44] Prominent industrial musicians include the Sheffield based groups Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire.[44] While the term was initially self-applied by a small coterie of groups and individuals associated with Industrial Records, it broadened to include artists influenced by the original movement or using an industrial aesthetic.

Jamaican music

Jamaican ska, rocksteady and reggae had been introduced to the United Kingdom in the 1960s, largely due to the Windrush immigration of the 60's and 50's, and the genres became especially popular with Mods, skinheads and suedeheads.[45] The 1970s saw the first major flowering of British reggae with bands such as The Cimarons, Aswad and Matumbi. Jamaican music began to influence British pop music, punk rock and the 2 Tone genre with the rise of the (often interracial) bands, such as The Specials, Madness, The Selecter and The Beat.[46] Many of these Jamaican-influenced UK bands (such as UB40) adopted pop styles to appeal to mainstream audiences, but some UK reggae bands (such as Steel Pulse) played songs with more confrontational socio-political lyrics.[47] The 1970s also saw the rise of dub poetry, exemplified by Linton Kwesi Johnson, Sister Netifa and Benjamin Zephaniah. The reggae subgenre lovers rock originated in the UK in the 1970s, and the Louisa Marks song "Caught You in a Lie" helped popularise the genre.[48]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Glam Rock Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- 1 2 "New Wave Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Prog-Rock/Art Rock". AllMusic. 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ↑ J. Atkins, The Who on record: a critical history, 1963-1998 (McFarland, 2000), p. 11.

- ↑ J. M. Curtis, Rock eras: interpretations of music and society, 1954–1984 (Popular Press, 1987), p. 236.

- ↑ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock (Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 378.

- ↑ J. Beethoven and C. Moore, Rock-It: Textbook (Alfred Music Publishing, 1980), ISBN 0-88284-473-3, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Graeme Thomson (13 May 2010). "Kate Bush's only tour: pop concert or disappearing act? The Guardian 13 May 2010". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ↑ "Kate Bush | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ D., Weinstein, Heavy Metal: The Music and its Culture (Da Capo, 2000). p. 14.

- 1 2 "Hard Rock", Allmusic, retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ P. Prown, H. P. Newquist and J. F. Eiche, Legends of Rock Guitar: the Essential Reference of Rock's Greatest Guitarists (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997), ISBN 0-7935-4042-9, p. 113.

- ↑ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 7.

- ↑ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 10.

- ↑ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 3.

- ↑ "Glam Rock". Encarta. Archived from the original on 13 January 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ↑ M. Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 1944–2002 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003).

- 1 2 3 4 B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- ↑ J. S. Sawyers, Celtic Music: A Complete Guide (Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press, 2001), pp. 1–12.

- ↑ "Pub Rock- Pre Punk music". Punk77.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ L. D. Smith, Elvis Costello, Joni Mitchell, and the Torch Song Tradition (Greenwood, 2004), p. 132.

- ↑ "Pub Rock Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ P. Murphy, "Shine On, The Lights of the Bowery: The Blank Generation Revisited", Hot Press, 12 July 2002; Hoskyns, Barney, "Richard Hell: King Punk Remembers the [ ] Generation", Rock's Backpages, March 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 "British Punk Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Post-Punk" Allmusic. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- ↑ Reynolds (2005), p. xxi.

- ↑ P. Buckley, The rough guide to rock (London: Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 801.

- 1 2 P. Gambaccini, T. Rice and J. Rice, British Hit Singles (6th edn., 1985), pp. 335–7.

- ↑ E. Macan, Rocking the classics: English progressive rock and the counterculture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 35–6.

- ↑ "The Man Who Dies Every Day - Ultravox | Song Info | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ J. Miller, Stripped: Depeche Mode (Omnibus Press, 2004), p. 21.

- ↑ "Synth Pop Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ B. Longhurst, Popular Music and Society (Wiley-Blackwell, 1995), p. 245.

- ↑ E. Vincentelli, ABBA Gold (Continuum, 2004), p. 50.

- ↑ S. Brown, Marketing: the Retro Revolution (SAGE, 2001), p. 131.

- ↑ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock: the definitive guide to more than 1200 artists and bands (London: Rough Guides, 2003), pp. 145, 211–12, 643–4.

- ↑ "Streets Of London, Ralph McTell", BBC Radio 2, Sold on Song, 19 February 2009.

- ↑ "Biddu: Futuristic Journey & Eastern Man". Dutton Vocalion. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ James Ellis. "Biddu". Metro. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ W. Kaufman, H. Slettedahl Macpherson, Britain and the Americas: culture, politics, and history (ABC-CLIO, 2005), pp. 504–5.

- ↑ A. Blake, The land without music: music, culture and society in twentieth-century Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), p. 149.

- ↑ E. Macan, Rocking the classics: English progressive rock and the counterculture (Oxford: Oxford University Press US, 1997), p. 132.

- ↑ "Industrial Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- 1 2 V.Vale. Re/Search #6/7: Industrial Culture Handbook, 1983.

- ↑ P. Childs and M. Storry, Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture (Taylor & Francis, 1999), p. 496.

- ↑ W. Kaufman and H. S. Macpherson, Britain and the Americas: culture, politics, and history (ABC-CLIO, 2005), p. 818.

- ↑ K. Walker, Dubwise: Reasoning From the Reggae Underground (Insomniac Press, 2005), p. 205.

- ↑ A. Donnell, Companion to contemporary Black British culture (London: Taylor & Francis, 2002), p. 185.