| |

| |

| Formerly | Tesla Motors, Inc. (2003–2017) |

|---|---|

| Type | Public |

| |

| ISIN | US88160R1014 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | July 1, 2003 in San Carlos, California, U.S. |

| Founders | See § Founding |

| Headquarters | Gigafactory Texas, Austin, Texas , U.S. |

Number of locations | 1,068 sales, service and delivery centers |

Area served |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | |

Production output |

|

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Elon Musk (21%) |

Number of employees | |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | tesla.com |

| Footnotes / references Financials as of December 31, 2022. References:[1][2][3][4][5] | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Companies

In popular culture

Related

|

||

Tesla, Inc. (/ˈtɛslə/ TESS-lə or /ˈtɛzlə/ TEZ-lə[lower-alpha 1]) is an American multinational automotive and clean energy company headquartered in Austin, Texas, which designs, manufactures and sells electric vehicles, stationary battery energy storage devices from home to grid-scale, solar panels and solar shingles, and related products and services.

Tesla was incorporated in July 2003 by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning as Tesla Motors. In February 2004 Elon Musk joined as the company's largest shareholder and in 2008 he was named CEO. The company's name is a tribute to inventor and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla. The company began production of its first car model, the Roadster sports car, in 2008, followed by the Model S sedan in 2012, the Model X SUV in 2015, the Model 3 sedan in 2017, the Model Y crossover in 2020, the Tesla Semi truck in 2022 and the Cybertruck pickup truck in 2023. The Model 3 is the all-time bestselling plug-in electric car worldwide, and in June 2021 became the first electric car to sell 1 million units globally.[7]

Tesla is one of the world's most valuable companies. In October 2021, Tesla's market capitalization temporarily reached $1 trillion, the sixth company to do so in U.S. history. As of 2023, it is the world's most valuable automaker. In 2022, the company led the battery electric vehicle market, with 18% share.

Tesla has been the subject of lawsuits, government scrutiny, and journalistic criticism, stemming from allegations of whistleblower retaliation, worker rights violations, product defects, and Musk's many controversial statements.

History

.jpg.webp)

Founding (2003–2004)

The company was incorporated as Tesla Motors, Inc. on July 1, 2003, by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning.[8][9] Eberhard and Tarpenning served as CEO and CFO, respectively.[10] Eberhard said that he wanted to build "a car manufacturer that is also a technology company", with its core technologies as "the battery, the computer software, and the proprietary motor".[11]

Ian Wright was Tesla's third employee, joining a few months later.[8] In February 2004, the company raised US$7.5 million (equivalent to $12 million in 2022) in series A funding, including $6.5 million (equivalent to $10 million in 2022) from Elon Musk, who had received $100 million from the sale of his interest in PayPal two years earlier. Musk became the chairman of the board of directors and the largest shareholder of Tesla.[12][13][10] J. B. Straubel joined Tesla in May 2004 as chief technical officer.[14]

A lawsuit settlement agreed to by Eberhard and Tesla in September 2009 allows all five – Eberhard, Tarpenning, Wright, Musk, and Straubel – to call themselves co-founders.[15]

Roadster (2005–2009)

Elon Musk took an active role within the company and oversaw Roadster product design at a detailed level, but was not deeply involved in day-to-day business operations.[16] The company's strategy was to start with a premium sports car aimed at early adopters and then move into more mainstream vehicles, including sedans and affordable compacts.[17]

In February 2006, Musk led Tesla's Series B venture capital funding round of $13 million, which added Valor Equity Partners to the funding team.[18][13] Musk co-led the third, $40 million round in May 2006 which saw investment from prominent entrepreneurs including Google co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, and former eBay President Jeff Skoll.[19] A fourth round worth $45 million in May 2007 brought the total private financing investment to over $105 million.[19]

Tesla's first car, the Roadster, was officially revealed to the public on July 19, 2006, in Santa Monica, California, at a 350-person invitation-only event held in Barker Hangar at Santa Monica Airport.[20]

In August 2007, Eberhard was asked by the board, led by Elon Musk, to step down as CEO.[21] Eberhard then took the title of "President of Technology" before ultimately leaving the company in January 2008. Co-founder Marc Tarpenning, who served as the Vice President of Electrical Engineering of the company, also left the company in January 2008.[22] In August 2007, Michael Marks was brought in as interim CEO, and in December 2007, Ze'ev Drori became CEO and President.[23] Musk succeeded Drori as CEO in October 2008.[23] In June 2009, Eberhard filed a lawsuit against Musk for allegedly forcing him out.[24]

Tesla began production of the Roadster in 2008 inside the service bays of a former Chevrolet dealership in Menlo Park.[25][26] By January 2009, Tesla had raised $187 million and delivered 147 cars. Musk had contributed $70 million of his own money to the company.[27]

In June 2009, Tesla was approved to receive $465 million in interest-bearing loans from the United States Department of Energy. The funding, part of the $8 billion Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program, supported the engineering and production of the Model S sedan, as well as the development of commercial powertrain technology.[28] Tesla repaid the loan in May 2013, with $12 million in interest.[29][30]

IPO, Model S, and Model X (2010–2015)

In May 2010, Tesla purchased what would later become the Tesla Factory in Fremont, California, from Toyota for $42 million,[31] and opened the facility in October 2010 to start production of the Model S.[32] On June 29, 2010, the company went public via an initial public offering (IPO) on the NASDAQ, the first American car company to do so since the Ford Motor Company had its IPO in 1956.[33] The company issued 13.3 million shares of common stock at a price of $17 per share, raising $226 million.[34]

In January 2012, Tesla ceased production of the Roadster, and in June the company launched its second car, the Model S luxury sedan.[35] The Model S won several automotive awards during 2012 and 2013, including the 2013 Motor Trend Car of the Year,[36] and became the first electric car to top the monthly sales ranking of a country, when it achieved first place in the Norwegian new car sales list in September 2013.[37] The Model S was also the bestselling plug-in electric car worldwide for the years 2015 and 2016.[38]

Tesla announced the Tesla Autopilot, a driver-assistance system, in 2014. In September that year, all Tesla cars started shipping with sensors and software to support the feature, with what would later be called "hardware version 1".[39]

Tesla entered the energy storage market, unveiling its Tesla Powerwall (home) and Tesla Powerpack (business) battery packs in April 2015.[40] The company received orders valued at $800 million within a week of the unveiling.[41]

Tesla began shipping its third vehicle, the luxury SUV Tesla Model X, in September 2015, which had 25,000 pre-orders at the time.[42][43]

SolarCity and Model 3 (2016–2018)

Tesla entered the solar installation business in November 2016 with the purchase of SolarCity, in an all-stock $2.6 billion deal.[44] The business was merged with Tesla's existing battery energy storage products division to form the Tesla Energy subsidiary.[45] The deal was controversial because at the time of the acquisition, SolarCity was facing liquidity issues of which Tesla's shareholders were not informed.[46] In February 2017, Tesla Motors changed its name to Tesla, Inc. to better reflect the scope of its expanded business.[47]

Tesla unveiled its first mass market vehicle in April 2016, the Model 3 sedan. Compared to Tesla's previous luxury vehicles, the Model 3 was less expensive and within a week the company received over 325,000 paid reservations.[48] In an effort to speed up production and control costs, Tesla invested heavily in robotics and automation to assemble the Model 3. Instead, the robotics actually slowed the production of the vehicles,[49] leading to significant delays and production problems, a period which the company would later come to describe as "production hell."[50][51] By the end of 2018, the production problems had been overcome, and the Model 3 would become the world's bestselling electric car from 2018 to 2021.[52][53]

This period of production hell put significant financial pressure on Tesla, and during this time it became one of the most shorted companies in the market. On August 8, 2018, amid the financial issues, Musk posted on social media that he was considering taking Tesla private.[54][55] The plan did not materialize and gave rise to much controversy and many lawsuits including a securities fraud charge from the SEC, which would force Musk to step down as the company's chairman, although he was allowed to remain CEO.

Global expansion and Model Y (2019–present)

From July 2019 to June 2020, Tesla reported four consecutive profitable quarters for the first time, which made it eligible for inclusion in the S&P 500.[56] Tesla was added to the index on December 21, 2020.[57] It was the most valuable company ever added, already the sixth-largest member.[57] During 2020, the share price increased 740%,[58] and on January 26, 2021, its market capitalization reached $848 billion,[59] more than the next nine largest automakers combined and becoming the US' 5th most valuable company.[60][61] In July 2020, Tesla reached a valuation of $206 billion, surpassing Toyota to become the world's most valuable automaker.[62] On August 31, 2020, Tesla completed a 5-for-1 stock split.[63]

Tesla introduced its second mass-market vehicle in March 2019, the Model Y mid-size crossover SUV, based on the Model 3.[64][65] Deliveries started in March 2020.[66]

During this period, Tesla invested heavily in expanding its production capacity, opening three new Gigafactories in quick succession. Construction of Gigafactory Shanghai started in January 2019, as the first automobile factory in China fully owned by a foreign company (not a joint venture).[67] The first production vehicle, a Model 3, rolled out of the factory in December, less than one year after groundbreaking.[68] Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg broke ground in February 2020,[69] and production of the Model Y began in March 2022.[70] Gigafactory Texas broke ground in June 2020,[71] and production of the Model Y began in April 2022.[72] Tesla has also announced plans for a Gigafactory Mexico to open in 2025.[73]

During the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, government officials in China closed Gigafactory Shanghai and lawmakers in California shut down production at the Tesla Fremont Factory. While China allowed Tesla to resume production a few weeks later, California did not. Tesla would ultimately defy state orders, and restart production on May 11, 2020.[74]

After the dispute with California officials, on December 1, 2021, Tesla moved its legal headquarters to Gigafactory Texas.[75][76] However, Tesla continued to use its former headquarters building in Palo Alto, and over the next two years significantly expanded its footprint in California. The company opened its Megafactory to build Megapack batteries in Lathrop, California in 2022,[77] and announced in February 2023 that it would establish a large global engineering headquarters in Palo Alto, moving into a corporate campus once owned by Hewlett Packard.[78]

Tesla became a major investor in bitcoin, acquiring $1.5 billion of the cryptocurrency,[79] and on March 24, 2021, the company started accepting bitcoin as a form of payment for US vehicle purchases.[80] However, after 49 days, the company ended bitcoin payments over concerns that the production of bitcoin was contributing to the consumption of fossil fuels, against the company's mission of encouraging the transition to sustainable energy.[81] After the announcement, the price of bitcoin dropped around 12%.[82] In July 2022 it was reported that Tesla had sold about 75% of its bitcoin holdings at a loss, citing that the cryptocurrency was hurting the company's profitability.[83]

Automotive products and services

As of November 2023, Tesla offers six vehicle models: Model S, Model X, Model 3, Model Y, Tesla Semi, and Cybertruck. Tesla's first vehicle, the first-generation Tesla Roadster, is no longer sold. Tesla has plans for a second-generation Roadster.

Available products

Model S

The Model S is a full-size luxury car with a liftback body style and a dual motor, all-wheel drive layout. Development of the Model S began prior to 2007 and deliveries started in June 2012. The Model S has seen two major design refreshes, first in April 2016 which introduced a new front-end design and again in June 2021 which revised the interior. The Model S was the top-selling plug-in electric car worldwide in 2015 and 2016. Since its introduction, more than 250,000 vehicles have been sold.

Model X

The Model X is a mid-size luxury crossover SUV offered in 5-, 6- and 7-passenger configurations with either a dual- or tri-motor, all-wheel drive layout. The rear passenger doors open vertically with an articulating "falcon-wing" design. A prototype Model X was first shown in February 2012 and deliveries started in September 2015.[84] The Model X shares around 30 percent of its content with the Model S. The vehicle has seen one major design refresh in June 2021 which revised the interior.

Model 3

The Model 3 is a mid-size car with a fastback body style and either a dual-motor, all-wheel drive layout or a rear-motor, rear-wheel drive layout. The vehicle was designed to be more affordable than the luxury Model S sedan. A prototype Model 3 was first shown in 2016 and within a week the company received over 325,000 paid reservations.[48] Deliveries started in July 2017.[85] The Model 3 ranked as the world's bestselling electric car from 2018 to 2021,[86][87][88] and cumulative sales passed 1 million in June 2021.[7] The vehicle has seen one major design refresh in September 2023 which revised the exterior and interior.

Model Y

The Model Y is a mid-size crossover SUV offered in 5- and 7-passenger configurations with a dual-motor, all-wheel drive layout. The vehicle was designed to be more affordable than the luxury Model X SUV. A prototype Model Y was first shown in March 2019,[64] and deliveries started in March 2020.[66] The Model Y shared around 75 percent of its content with the Model 3.[65] In the first quarter of 2023, the Model Y outsold the Toyota Corolla to become the world's best-selling car, the first ever electric vehicle to claim the title.[89]

Tesla Semi

.jpg.webp)

The Tesla Semi Class 8 semi-truck by Tesla, Inc. with a tri-motor, rear-wheel drive layout. Tesla claims that the Semi has approximately three times the power of a typical diesel semi truck, a range of 500 miles (800 km).[90] Two prototype trucks were first shown in November 2017 and initial deliveries were made to PepsiCo on December 1, 2022.[91] As of July 2023, the truck remains in pilot production,[3] and Tesla does not expect the truck to enter volume production before 2024, due to limited availability of the required 4680 battery cells.[92]

Cybertruck

The Cybertruck is a full-sized pickup truck. First announced in November 2019, pilot production began in July 2023, with deliveries beginning on November 30, 2023 after being pushed back multiple times. Three models are offered: rear-wheel drive, dual-motor all-wheel drive, and tri-motor all-wheel drive, with EPA range estimates of 320–340 miles (510–550 km), depending on the model. The truck's exterior design made from flat sheets of unpainted stainless steel earned a notably polarizing reception from media.[93][94][95]

Announced products

Roadster (second generation)

.jpg.webp)

On November 16, 2017, Tesla unveiled the second generation Roadster with a purported range of 620 miles (1,000 km) with a 200 kilowatt-hours (720 MJ) battery pack that would achieve 0–60 miles per hour (0–97 km/h) in 1.9 seconds; and 0–100 mph (0–161 km/h) in 4.2 seconds,[96] and a top speed over 250 mph (400 km/h). A "SpaceX Package" would include cold-gas thrusters.[97] The vehicle would have three electric motors, allowing all-wheel drive and torque vectoring during cornering.[97] The base price was set at $200,000.[97] Musk has said that the Roadster should ship in 2024.[98]

Tesla next-generation vehicle

The Tesla next-generation vehicle is an announced battery electric platform. It would become the third platform for the company. Vehicles based on this platform are not expected before 2025.[99]

Discontinued product

Tesla Roadster

The original Tesla Roadster[100] was a two-seater sports car, evolved from the Lotus Elise chassis.[101] It was produced from 2008 to 2012. The Roadster was the first highway-legal serial production electric car to use lithium-ion battery cells and the first production all-electric car to travel more than 200 miles (320 km) per charge.

Connectivity services

Tesla cars come with "Standard Connectivity", which provides navigation using a cellular connection. For a fee, Tesla offers a subscription to "Premium Connectivity" which adds live traffic and satellite maps to navigation, internet browsing, and media streaming.[102]

Vehicle servicing

Tesla service strategy is to service its vehicles first through remote diagnosis and repair. If it is not possible to resolve a problem remotely, customers are referred to a local Tesla-owned service center, or a mobile technician is dispatched.[103][104] Tesla has said that it does not want to make a profit on vehicle servicing, which has traditionally been a large profit center for most auto dealerships.[105]

In 2016, Tesla recommended having any Tesla car inspected every 12,500 miles or once a year, whichever comes first. In early 2019, the manual was changed to say: "your Tesla does not require annual maintenance and regular fluid changes," and instead it recommends periodic servicing of the brake fluid, air conditioning, tires and air filters.[106]

Charging services

Supercharger network

Supercharger is the branding used by Tesla for its high-voltage direct current fast chargers.

Destination charging location network

Tesla also has a network of "Destination Chargers," slower than Superchargers and intended for locations where customers are expected to park and stay for several hours, such as hotels, restaurants, or shopping centers. Unlike the Supercharger network, Tesla does not own the destination chargers, instead, property owners setup the devices and set pricing.[107] When the network first launched in 2014, Tesla provided free charging equipment and covered installation costs.[108] One of the largest providers is hotel chain Hilton Worldwide which in 2023 announced an agreement with Tesla to install 20,000 chargers across 2,000 of its properties in North America by 2025.[109]

Insurance services

Tesla has offered its own vehicle insurance in the United States since 2017 and has been acting as an independent insurance producer since 2021 as Tesla Insurance Services, Inc. It was introduced after the American Automobile Association (AAA), a major insurance carrier, raised rates for Tesla owners in June 2017 after a report concluded that the automakers vehicles crashed more often and were more expensive to repair than comparable vehicles.[110] A second study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety confirmed the findings.[111]

The company says that it uniquely understands its vehicles, technology and repair costs, and can eliminate traditional insurance carriers' additional charges.[112] In states where allowed, the company uses individual vehicle data to offer personalized pricing that can increase or decrease in cost based on the prior month's driving safety score.[113] As of 2023, insurance was available in 12 states.[114]

As of January 2023, Tesla offers insurance in the U.S. states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Utah and Virginia. The company also offers insurance for Tesla vehicle owners with non-Tesla vehicles.[112]

Energy products

.jpg.webp)

Tesla subsidiary Tesla Energy develops, builds, sells and installs solar energy generation systems and battery energy storage products (as well as related products and services) to residential, commercial and industrial customers. The subsidiary was created by the merger of Tesla's existing battery energy storage products division with SolarCity, a solar energy company that Tesla acquired in 2016.[115] In 2022, the company deployed solar energy systems capable of generating 348 megawatts, an increase of 3 megawatts over 2021, and deployed 6.5 gigawatt-hours of battery energy storage products, an increase of 64% over 2021.[116]

Tesla Energy products include solar panels (built by other companies for Tesla), the Tesla Solar Roof (a solar shingle system) and the Tesla Solar Inverter. Storage products include the Powerwall (a home energy storage device) and the Megapack (a large-scale energy storage system).[117][118][119]

For large-scale customers, Tesla Energy operates an online platform which allows for automated, real-time power trading, demand forecasting and product control.[120][121][122] In March 2021, the company said its online products were managing over 1.2 GWh of storage.[123] For home customers, the company operates a virtual power company in Texas called Tesla Electric, which utilizes the company's online platforms to manage customers Powerwall devices, discharging them into the grid to sell power when prices are high, earning money for customers.[124][125]

Business strategy

At the time of Tesla's founding in 2003, electric vehicles were very expensive.[126] In 2006, Elon Musk stated that Tesla's strategy was to first produce high-price, low-volume vehicles, such as sports cars, for which customers are less sensitive to price. This would allow them to progressively bring down the cost of batteries, which in turn would allow them to offer cheaper and higher volume cars.[17][127] Tesla's first vehicle, the Roadster, was low-volume (fewer than 2,500 were produced) and priced at over $100,000. The next models, the Model S and Model X, are more affordable but still luxury vehicles. The most recent models, the Model 3 and the Model Y, are priced still lower, and aimed at a higher volume market,[128][129] selling over 100,000 vehicles each quarter. Tesla continuously updates the hardware of its cars rather than waiting for a new model year, as opposed to nearly every other car manufacturer.[130]

Unlike other automakers, Tesla does not rely on franchised dealerships to sell vehicles. Instead, the company directly sells vehicles through its website and a network of company-owned stores.[131][132] The company is the first automaker in the United States to sell cars directly to consumers.[133][134] Some jurisdictions, particularly in the United States, prohibit auto manufacturers from directly selling vehicles to consumers. In these areas, Tesla has locations that it calls galleries that the company says "educate and inform customers about our products, but such locations do not actually transact in the sale of vehicles."[135][136] In total, Tesla operates nearly 400 stores and galleries in more than 35 countries.[137] These locations are typically located in retail shopping districts, inside shopping malls, or other high-traffic areas,[132] instead of near other auto dealerships.[138][139][140]

Analysts describe Tesla as vertically integrated given how it develops many components in-house, such as batteries, motors, and software.[142] The practice of vertical integration is rare in the automotive industry, where companies typically outsource 80% of components to suppliers and focus on engine manufacturing and final assembly.[143][144][145]

Tesla generally allows its competitors to license its technology, stating that it wants to help its competitors accelerate the world's use of sustainable energy.[146] Licensing agreements include provisions whereby the recipient agrees not to file patent suits against Tesla, or to copy its designs directly.[147] Tesla retains control of its other intellectual property, such as trademarks and trade secrets to prevent direct copying of its technology.[148]

Technology

Tesla is highly vertically integrated and develops many components in-house, such as batteries, motors, and software.[142]

Batteries

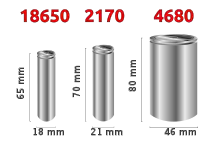

As of 2023, Tesla uses four different battery cell form factors: 18650, 2170, 4680, and prismatic.[149][150][151]

Tesla purchases these batteries from three suppliers, CATL, LG Energy Solution, and Panasonic, the latter of which has co-located some of its battery production inside Tesla's Gigafactory Nevada. Tesla is also currently building out the capacity to produce its own batteries.

Tesla batteries sit under the vehicle floor to save interior space. Tesla uses a multi-part aluminum and titanium protection system to protect the battery from road debris and/or vehicle crashes.[152]

Business analysis company BloombergNEF estimated Tesla's battery pack cost in 2021 at $112 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), versus an industry average of $132 per kWh.[153]

18650

Tesla was the first automaker to use cylindrical, lithium-ion battery cells. When it built the first generation Roadster, it used off-the-shelf 18650-type (18 mm diameter, 65 mm height) cylindrical batteries that were already used for other consumer electronics. The cells provided an engineering challenge because each has a relatively low capacity, so thousands needed to be bundled together in a battery pack. Electrical and thermal management also proved to be a challenge, requiring liquid cooling and an intumescent fire prevention chemical.[154] However, the decision proved to be pragmatic because there was already a mature manufacturing process that could produce a high volume of the cells at a consistent quality. Although the 18650-type cells are the oldest technology, they are used in the Model S and X vehicles. Tesla sources these batteries with a nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) cathode chemistry from Panasonic's factories in Japan.[155]

2170

The next battery type to be used was 2170-type (21 mm diameter, 70 mm height) cylindrical cell. The larger size was optimized for electric cars, allowing for a higher capacity per cell and a lower number of cells per battery pack. The 2170 was introduced for the Model 3 and Y vehicles.[155]

For vehicles built at the Tesla Fremont Factory, the company sources 2170-type batteries with a nickel-cobalt-aluminum cathode chemistry from Panasonic's production line at Gigafactory Nevada.[156] In January 2021, Panasonic had the capacity to produce 39 GWh per year of battery cells there.[157] Tesla Energy also uses 2170 cells in its Powerwall home energy storage product.

For vehicles made at Gigafactory Shanghai and Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg batteries with a nickel-cobalt-manganese (NMC) cathode chemistry are sourced from LG Energy Solution's factories in China.[155]

4680

Tesla's latest cylindrical cell design is the 4680-type (46 mm diameter, 80 mm height) introduced in 2021. The battery was developed in-house by Tesla and is physically 5-times bigger than the 2170-type, again allowing for a higher capacity per cell and a lower number of cells per battery pack.[158][159] Currently, Tesla builds the 4680 cells itself and has not disclosed the cathode chemistry. The company has already opened production lines in Fremont, California, and plans to open lines inside Gigafactory Nevada and Gigafactory Texas. The 4680 cells are used in the Model Y and Cybertruck built at Gigafactory Texas.[155]

Prismatic

Tesla also uses prismatic (rectangular) cells in many entry-level Model 3 and Model Y vehicles.[155] The prismatic cells are a lithium iron phosphate battery (LFP or LiFePO

4) which is a less energy-dense type, but do not contain any nickel or cobalt, which makes it less expensive to produce.[160] Tesla sources these batteries from CATL's factories in China. As of April 2022, nearly half of Tesla's vehicle production used prismatic cells.[161] Tesla Energy also uses prismatic cells in its Megapack grid-scale energy storage product.[162]

Research

Tesla invests in lithium-ion battery research. In 2016, the company established a 5-year battery research and development partnership at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, with lead researcher Jeff Dahn.[163][164][165][166] Tesla acquired Maxwell Technologies for over $200 million[167] – and sold in 2021.[168] It also acquired Hibar Systems.[169][170] Tesla purchased several battery manufacturing patent applications from Springpower International, a small Canadian battery company.[171][172]

Software

Tesla uses over-the-air updates to deliver updates to vehicles, adding features or fixing problems.[173] This is enabled by tight integration between a few powerful onboard computers, compared to the way automakers had previously handled technology, by purchasing off-the-shelf electronic components for each subsystem that typically could not interface at the software level.[174]

The system also has allowed Tesla to control which features customers have access to. For example, for ease of assembly all Model 3 vehicles were built with heated rear seats, but only customers who purchased a premium interior could turn them on. However, Tesla has allowed customers who didn't pay for a premium interior to purchase access to the heated rear seats.[175] Tesla uses a similar software lock feature for Enhanced Autopilot and Full-Self Driving features, even though all vehicles are equipped with the computers and cameras necessary to enable those features.[176]

Motors

Tesla makes two kinds of electric motors. Its oldest design in production is a three-phase four-pole alternating current induction motor (asynchronous motor) with a copper rotor[177] (which inspired the Tesla logo). These motors use electromagnetic induction, by varying magnetic field to produce torque. Induction motors are used as the rear motor in the Model S and Model X, as the front motor in the Model 3 and Model Y and were used in the first-generation Roadster.

Newer, higher efficiency permanent magnet motors have been in use since the introduction of the Model 3 in 2017. They are currently used as the rear motor in the Model 3 and Model Y, the front motor of 2019-onward versions of the Model S and X, and are expected to be used in the Tesla Semi.[178] The permanent magnet motors are more efficient, especially in stop-start driving.[179]

North American Charging Standard

The North American Charging Standard (NACS) is an electric vehicle charging connector system developed by Tesla. It has been used on all North American market Tesla vehicles since 2012 and was opened for use to other manufacturers in 2022. Since then, nearly every other vehicle manufacturer has announced that starting from 2025, their electric vehicles sold in North America will be equipped with the NACS charge port. Several electric vehicle charging network operators and equipment manufacturers have also announced plans to add NACS connectors.[180]

Autopilot

Autopilot is an advanced driver-assistance system developed by Tesla. The system requires active driver supervision at all times.[181]

Since September 2014, all Tesla cars are shipped with sensors (initially hardware version 1 or "HW1") and software to support Autopilot.[182] Tesla upgraded its sensors and software in October 2016 ("HW2") to support full self-driving in the future.[183] HW2 includes eight cameras, twelve ultrasonic sensors, and forward-facing radar.[183] HW2.5 was released in mid-2017, and it upgraded HW2 with a second graphics processing unit (GPU) and, for the Model 3 only, a driver-facing camera.[184] HW3 was released in early 2019 with an updated and more powerful computer, employing a custom Tesla-designed system on a chip.[185]

In April 2019, Tesla announced that all of its cars will include Autopilot software (defined as just Traffic-Aware Cruise Control and Autosteer (Beta)) as a standard feature moving forward.[186] Full self-driving software (Autopark, Navigate on Autopilot (Beta), Auto Lane Change (Beta), Summon (Beta), Smart Summon (Beta) and future abilities) is an extra cost option.[186]

In 2020, Tesla released software updates where its cars recognize and automatically stop at stop signs and traffic lights.[187][188][189] In May 2021, Tesla removed the radar sensor and radar features from its Model 3 and Model Y vehicles, opting instead to rely on camera vision alone.[190][191][192] The New York Times reported in December 2021 that Musk "repeatedly told members of the Autopilot team that humans could drive with only two eyes and that this meant cars should be able to drive with cameras alone," an analogy some experts and former Tesla engineers described as "deeply flawed."[193] Similarly, a statistical analysis conducted in A Methodology for Normalizing Safety Statistics of Partially Automated Vehicles debunked a common Tesla claim that Autopilot reduced crash rates by 40 percent[194] by accounting for the relative safety of the given operating domain when using active safety measures.[195]

Full Self-Driving

Full Self-Driving (FSD) is an optional extension of Autopilot promoted as eventually being able to perform fully autonomous driving. At the end of 2016, Tesla expected to demonstrate full autonomy by the end of 2017,[196] which as of July 2022 has not occurred.[197] The first beta version of the software was released on October 22, 2020, to a small group of testers.[198] The release of the beta has renewed concern regarding whether the technology is ready for testing on public roads.[199][200] The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has called for "tougher requirements" for any testing of Autopilot on public roads.[201]

Tesla's approach to achieve full autonomy is different from that of other companies.[202] Whereas Waymo, Cruise, and other companies are relying on highly detailed (centimeter-scale) three-dimensional maps, lidar, and cameras, as well as radar and ultrasonic sensors in their autonomous vehicles, Tesla's approach is to use coarse-grained two-dimensional maps and cameras (no lidar) as well as radar and ultrasonic sensors.[202][203] Tesla claims that although its approach is much more difficult, it will ultimately be more useful, because its vehicles will be able to self-drive without geofencing concerns.[204] Tesla's self-driving software has been trained on over 20 billion miles driven by Tesla vehicles as of January 2021.[205] Tesla also designed a self-driving computer chip that has been installed in its cars since March 2019.[206]

Most experts believe that Tesla's approach of trying to achieve full self-driving by eschewing lidar and high-definition maps is not feasible.[207][208][209] In March 2021, according to a letter that Tesla sent to the California Department of Motor Vehicles about FSD's capability – acquired by PlainSite via a public records request – Tesla stated that FSD is not capable of autonomous driving and is only at Society of Automotive Engineers Level 2 automation.[210] In a May 2021 study by Guidehouse Insights, Tesla was ranked last for both strategy and execution in the autonomous driving sector.[211] In October 2021, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) called on Tesla to change the design of its Autopilot to ensure it cannot be misused by drivers, according to a letter sent to Musk.[212]

Robotics

Ahead of the start of production of the Model 3, Tesla invested heavily in robotics and automation to assemble vehicles. To that end, between 2015 and 2017, the company purchased several companies involved in automation and robotics including Compass Automation,[213] Grohmann Automation,[214] Perbix Machine Company, and Riviera Tool and Die.[215] Elon Musk later admitted that the robotics actually slowed the production of the vehicles.[49]

Tesla uses massive casting machines (Giga Press) to make large single pieces of vehicle underbodies and to streamline production.[216] This saves time, labor, cost and factory space, replacing multiple robots that weld car parts together with a single machine.[217]

In September 2022, Tesla revealed prototypes of a humanoid robot named Optimus, which Musk has stated uses the same core software as FSD. During the presentations at Tesla's AI Day 2022, Musk suggested that, among other use cases, the finalized version of Optimus could be used in Tesla's car factories to help with repetitive tasks and relieve labor shortages.[218]

In July 2023, Tesla acquired Wiferion, a Germany-based developer of wireless charging systems for industrial vehicles and autonomous robots, which has since been operating as Tesla Engineering Germany GmbH.[219] Tesla sold the business to Munich-based Puls Group three months later, but retained its staff.[220][221]

Glass

In November 2016, the company announced the Tesla Glass technology group. The group produced the roof glass for the Tesla Model 3. It also produces the glass used in the Tesla Solar Roof's solar shingles.[222]

Facilities

The company operates seven large factories and about a dozen smaller factories around the world. As of 2023, the company also operates more than 1,000 retail stores, galleries, service, delivery and body shop locations globally.[3]

| Opened | Name | City | Country | Employees | Products | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Tesla Fremont Factory | Fremont, California | United States | 22,000 | Model S, Model X, Model 3, Model Y | [31][223][224] |

| 2016 | Gigafactory Nevada | Storey County, Nevada | United States | 7,000 | Batteries, Powerwall, Semi | [225][226][227] |

| 2017 | Gigafactory New York | Buffalo, New York | United States | 1,500 | Solar Roof, Supercharger | [228][229] |

| 2019 | Gigafactory Shanghai | Shanghai | China | 20,000 | Model 3, Model Y, Supercharger | [230][231] |

| 2022 | Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg | Grünheide | Germany | 10,000 | Model Y (planned: batteries, Model 3) | [232][233][234] |

| 2022 | Gigafactory Texas | Austin, Texas | United States | 12,000 | Cybertruck, Model Y (planned: batteries, Next-gen vehicle) | [235][236][237] |

North America

Tesla was founded in San Carlos, California.[238] In 2010, Tesla moved its corporate headquarters and opened a powertrain development facility in Palo Alto.[239] Tesla's first retail store was opened in 2008 in Los Angeles.[240]

Tesla's first assembly plant occupies the former NUMMI plant in Fremont, California, known as the Tesla Fremont Factory. The factory was originally opened by General Motors in 1962, and then operated by NUMMI, a joint venture of GM and Toyota from 1984.[241] The joint venture ended when GM entered bankruptcy in 2009. In 2010, Toyota agreed to sell the plant to Tesla at a significant discount.[31]

Tesla's first purpose-built facility was opened in Nevada in 2016. Gigafactory Nevada produces Powerwalls, Powerpacks and Megapacks;[225] battery cells in partnership with Panasonic;[242] and Model 3 drivetrains.[243] The factory received substantial subsidies (abatements and credits) from the local and state government, that, in exchange for opening in their jurisdiction, allowed Tesla to operate essentially tax free for 10 years.[244]

As part of the acquisition of SolarCity in 2016, Tesla gained control of Gigafactory New York in Buffalo on the site of a former Republic Steel plant. The state of New York spent cash to build and equip the factory through the Buffalo Billion program.[245][246] In 2017, the factory started production of the Tesla Solar Roof,[228] but faced multiple production challenges. Since 2020, Tesla has also assembled Superchargers in New York. The plant has been criticized for offering little economic benefit for the state funding.[247]

On July 23, 2020, Tesla picked Austin, Texas, as the site of its fifth Gigafactory, since then known as Gigafactory Texas.[248] Giga Texas is the only factory that produces the Tesla Cybertruck and produces Model Y cars for the Eastern United States. On April 7, 2022, Tesla celebrated the opening of the facility in a public event.[72]

On December 1, 2021, Tesla relocated its legal headquarters from Palo Alto, California, to the Gigafactory site in Austin, Texas.[249]

Tesla acquired a former JC Penney distribution center near Lathrop, California, in 2021 to build the "Megafactory" to manufacture the Megapack, the company's large scale energy storage product.[250][251] The location opened in 2022.

Tesla announced in February it would open a new global engineering headquarters in Palo Alto, moving into a corporate campus once owned by Hewlett Packard, located a couple of miles from Tesla's former headquarters.

Tesla plans to open Gigafactory Mexico, the company's sixth Gigafactory near Monterrey, Mexico in 2025.

Europe

Tesla opened its first European store in June 2009 in London.[252] Tesla's European headquarters are in the Netherlands,[253] part of a group of Tesla facilities in Tilburg, including the company's European Distribution Centre.[254]

In late 2016, Tesla acquired German engineering firm Grohmann Engineering as a new division dedicated to helping Tesla increase the automation and effectiveness of its manufacturing process.[255] After winding down existing contracts with other manufacturers, the renamed Tesla Automation now works exclusively on Tesla projects.[256]

Tesla announced its plans to build a car and battery factory in Europe in 2016.[257] Several countries campaigned to be the host,[258] and eventually Germany was chosen in November 2019.[259] On March 22, 2022, Tesla's first European Gigafactory named Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg[260][261] opened with planned capacity to produce 500,000 electric vehicles annually as well as batteries for the cars.[261]

Asia

Tesla opened its first showroom in Asia in Tokyo, Japan, in October 2010.[263]

In July 2018, Tesla signed an agreement with Chinese authorities to build a factory in Shanghai, China, which was Tesla's first Gigafactory outside of the United States.[264] The factory building was finished in August 2019, and the initial Tesla Model 3s were in production from Gigafactory Shanghai in October 2019.[230] In 2021, China accounted for 26% of Tesla sales revenue, and was the second largest market for Tesla after the United States, which accounted for 45% of its sales.[265]

Tesla has expressed interest in expanding to India and perhaps building a future Gigafactory in the country.[266] The company established a legal presence in the nation in 2021 and plans to open an office in Pune starting in October 2023.[267]

Partners

Panasonic

In January 2010, Tesla and battery cell maker Panasonic announced that they would together develop nickel-based lithium-ion battery cells for electric vehicles.[268] The partnership was part of Panasonic's $1 billion investment over three years in facilities for lithium-ion cell research, development and production.[269]

Beginning in 2010, Panasonic invested $30 million for a multi-year collaboration on new battery cells designed specifically for electric vehicles.[270] In July 2014, Panasonic reached a basic agreement with Tesla to participate in battery production at Giga Nevada.[271]

Tesla and Panasonic also collaborated on the manufacturing and production of photovoltaic (PV) cells and modules at the Giga New York factory in Buffalo, New York.[228] The partnership started in mid-2017 and ended in early 2020, before Panasonic exited the solar business entirely in January 2021.[272][273]

In March 2021, the outgoing CEO of Panasonic stated that the company plans to reduce its reliance on Tesla as their battery partnership evolves.[274]

Other current partners

Tesla has long-term contracts in place for lithium supply. In September 2020, Tesla signed a sales agreement with Piedmont Lithium to buy high-purity lithium ore for up to ten years,[275] specifically to supply "spodumene concentrate from Piedmont's North Carolina mineral deposit".[276] In 2022, Tesla contracted for 110,000 tonnes of spodumene concentrate over four years from the Core Lithium's lithium mine in the Northern Territory of Australia.[277]

Tesla also has a range of minor partnerships, for instance working with Airbnb and hotel chains to install destination chargers at selected locations.[278]

Former partners

Daimler

Daimler and Tesla began working together in late 2007. On May 19, 2009, Daimler bought a stake of less than 10% in Tesla for a reported $50 million.[280][281] As part of the collaboration, Herbert Kohler, vice-president of E-Drive and Future Mobility at Daimler, took a Tesla board seat.[282] On July 13, 2009, Daimler sold 40% of its acquisition to Aabar, an investment company controlled by the International Petroleum Investment Company owned by the government of Abu Dhabi.[283] In October 2014, Daimler sold its remaining holdings for a reported $780 million.[284]

Tesla supplied battery packs for Freightliner Trucks in 2010.[285][286] The company also built electric-powertrain components for the Mercedes-Benz A-Class E-Cell, with 500 cars planned to be built for trial in Europe beginning in September 2011.[287][288] Tesla produced and co-developed the Mercedes-Benz B250e's powertrain, which ended production in 2017.[289] The electric motor was rated 134 hp (100 kW) and 230 pound force-feet (310 N⋅m), with a 36 kWh (130 MJ) battery. The vehicle had a driving range of 200 km (124 mi) with a top speed of 150 km/h (93 mph).[290] Daimler division Smart produced the Smart ED2 cars from 2009 to 2012 which had a 14-kilowatt-hour (50 MJ) lithium-ion battery from Tesla.[291][292]

Toyota

In May 2010, Tesla and Toyota announced a deal in which Tesla purchased the former NUMMI factory from Toyota for $42 million, Toyota purchased $50 million in Tesla stock, and the two companies collaborated on an electric vehicle.[31]

In July 2010, the companies announced they would work together on a second generation Toyota RAV4 EV.[293] The vehicle was unveiled at the October 2010 Los Angeles Auto Show and 35 pilot vehicles were built for a demonstration and evaluation program that ran through 2011. Tesla supplied the lithium metal-oxide battery and other powertrain components[294][295] based on components from the Roadster.[296]

The production version was unveiled in August 2012, using battery pack, electronics and powertrain components from the Tesla Model S sedan (also launched in 2012).[297] The RAV4 EV had a limited production run which resulted in just under 3,000 vehicles being produced, before it was discontinued in 2014.[298][299]

According to Bloomberg News, the partnership between Tesla and Toyota was "marred by clashes between engineers".[300] Toyota engineers rejected designs that Tesla had proposed for an enclosure to protect the RAV4 EV's battery pack. Toyota took over responsibility for the enclosure's design and strengthened it. In 2014, Tesla ended up adding a titanium plate to protect the Model S sedan's battery after some debris-related crashes lead to cars catching fire.[300][152] On June 5, 2017, Toyota announced that it had sold all of its shares in Tesla and halted the partnership.[301][302]

Mobileye

Initial versions of Autopilot were developed in partnership with Mobileye beginning in 2014.[303] Mobileye ended the partnership on July 26, 2016, citing "disagreements about how the technology was deployed."[304]

Lawsuits and controversies

Sexual harassment

In 2021, seven women came forward with claims of having faced sexual harassment and discrimination while working at Tesla's Fremont factory.[305] They accused the company of facilitating a culture of rampant sexual harassment. The women said they were consistently subjected to catcalling, unwanted advances, unwanted touching, and discrimination while at work. "I was so tired of the unwanted attention and the males gawking at me I proceeded to create barriers around me just so I could get some relief," Brooks told The Washington Post. "That was something I felt necessary just so I can do my job." Stories range from intimate groping to being called out to the parking lot for sex.[306]

Women feared calling Human Resources for help as their supervisors were often participants.[307] Musk himself is not indicted, but most of the women pressing charges believe their abuse is connected to the behavior of CEO Elon Musk. They cite his crude remarks about women's bodies, wisecracks about starting a university that abbreviated to "T.IT.S", and his generally dismissive attitude towards reporting sexual harassment.[308] "What we're addressing for each of the lawsuits is just a shocking pattern of rampant harassment that exists at Tesla," said attorney David A. Lowe.[307] In 2017, another woman had accused Tesla of very similar behavior and was subsequently fired. In a statement to the Guardian, Tesla confirmed the company had fired her, saying it had thoroughly investigated the employee's allegations with the help of "a neutral, third-party expert" and concluded her complaints were unmerited.[309]

In May 2022, a California judge ruled that the sexual harassment lawsuit could move to court, rejecting Tesla's request for closed-door arbitration.[310]

Labor disputes

United States

In June 2016, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) took issue with Tesla's use of nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) regarding customer repairs[311] and, in October 2021, the NHTSA formally asked Tesla to explain its NDA policy regarding customers invited into the FSD Beta.[312] Tesla has used NDAs on multiple occasions with both employees[313] and customers[314] to allegedly prevent possible negative coverage.[315][316]

From 2014 to 2018, Tesla's Fremont Factory had three times as many Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) violations as the ten largest U.S. auto plants combined.[317] An investigation by the Reveal podcast alleged that Tesla "failed to report some of its serious injuries on legally mandated reports" to downplay the extent of injuries.[318]

In January 2019, former Tesla security manager Sean Gouthro filed a whistleblower complaint alleging that the company had hacked employees' phones and spied on them, while also failing to report illegal activities to the authorities and shareholders.[319][320][321] Several legal cases have revolved around alleged whistleblower retaliation by Tesla. These include the dismissal of Tesla safety official Carlos Ramirez[322][323] and Tesla security employee Karl Hansen.[324] In 2020, the court ordered Hansen's case to arbitration.[325] In June 2022, the arbitrator filed an unopposed motion with the court stating Hansen "has failed to establish the claims...Accordingly his claims are denied, and he shall take nothing".[326]

In September 2019, a California judge ruled that 12 actions in 2017 and 2018 by Musk and other Tesla executives violated labor laws because they sabotaged employee attempts to unionize.[327][328]

In March 2021, the US National Labor Relations Board ordered Musk to remove a tweet and reinstate a fired employee over union organization activities.[329][330] Later, after appealing, a federal appeals court upheld the decision.[331]

The California Civil Rights Department filed a suit in 2022 alleging "a pattern of racial harassment and bias" at the Tesla Fremont factory. As of April 2023, the department is also conducting a probe of the factory based on a 2021 complaint and claims that Tesla has been obstructing the investigation.[332]

Europe

In October 2023, a strike was initiated by the Swedish labor union IF Metall against a Tesla subsidiary due to the company's refusal to sign a collective agreement. The strike initially involved approximately 120 mechanics at ten workshops servicing Tesla vehicles and later expanded via solidarity strikes to include services provided by postmen, electricians, and other workers involved with Tesla operations.[333][334][335]

Fraud allegations

There have been numerous concerns about Tesla's financial reporting. In 2013, Bloomberg News questioned whether Tesla's financial reporting violated Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) reporting standards.[336] Fortune accused Tesla in 2016 of using creative accounting to show positive cash flow and quarterly profits.[337] In 2018, analysts expressed concerns over Tesla's accounts receivable balance.[338] In September 2019, the SEC questioned Tesla CFO Zach Kirkhorn about Tesla's warranty reserves and lease accounting.[339] In a letter to his clients, hedge fund manager David Einhorn, whose firm suffered losses from its short position against Tesla that quarter, accused Elon Musk in November 2019 of "significant fraud",[340][341] and publicly questioned Tesla's accounting practices, telling Musk that he was "beginning to wonder whether your accounts receivable exist."[342]

From 2012 to 2014, Tesla earned more than $295 million in Zero Emission Vehicle credits for a battery-swapping technology that was never made available to customers.[343] Staff at California Air Resources Board were concerned that Tesla was "gaming" the battery swap subsidies and in 2013 recommended eliminating the credits.[344]

A consolidated shareholders lawsuit alleges that Musk knew SolarCity was going broke before the acquisition, that he and the Tesla board overpaid for SolarCity, ignored their conflicts of interest and breached their fiduciary duties in connection with the deal, and failed to disclose "troubling facts" essential to an analysis of the proposed acquisition.[345] The members of the board settled in 2020, leaving Musk as the only defendant.[346] In April 2022, the Delaware Court of Chancery ruled in favor of Musk,[347][348] and its ruling was upheld by the Delaware Supreme Court in June 2023.[349]

In August 2018, Elon Musk tweeted, "Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured."[350] The tweet caused the stock to initially rise but then drop when it was revealed to be false.[351][352][353] Musk settled fraud charges with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) over his false statements in September 2018. According to the terms of the settlement, Musk agreed to have his tweets reviewed by Tesla's in-house counsel, he was removed from his chairman role at Tesla temporarily, and two new independent directors were appointed to the company's board.[354] Tesla and Musk also paid civil penalties of $20 million each.[354] A civil class-action shareholder lawsuit over Musk's statements and other derivative lawsuits were also filed against Musk and the members of Tesla's board of directors, as then constituted, in regard to claims and actions made that were associated with potentially going private.[355][356] In February 2023, a California jury unanimously found Musk and Tesla not liable in the class-action lawsuit.[357]

In September 2018, Tesla disclosed that it was under investigation by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) regarding its Model 3 production figures.[358] Authorities were investigating whether the company misled investors and made projections about its Model 3 production that it knew would be impossible to meet.[358] A stockholder class action lawsuit against Tesla related to Model 3 production numbers (unrelated to the FBI investigation) was dismissed in March 2019.[359][360][361]

Tesla US dealership disputes

Unlike other automakers, Tesla does not rely on franchised auto dealerships to sell vehicles and instead directly sells vehicles through its website and a network of company-owned stores. In some areas, Tesla operates locations called "galleries" which "educate and inform customers about our products, but such locations do not actually transact in the sale of vehicles."[135] This is because some jurisdictions, particularly in the United States, prohibit auto manufacturers from directly selling vehicles to consumers. Dealership associations have filed lawsuits to prevent direct sales. These associations argued that the franchise system protects consumers by encouraging dealers to compete with each other, lowering the price a customer pays. They also claimed that direct sales would allow manufacturers to undersell their own dealers.[138] The United States Federal Trade Commission ultimately disproved the associations' claims and recommended allowing direct manufacturer sale, which they concluded would save consumers 8% in average vehicle price.[362][363][364]

Tesla has also lobbied state governments for the right to directly sell cars.[365] The company has argued that directly operating stores improves consumer education about electric vehicles,[135] because dealerships would sell both Tesla and gas-powered vehicles. Doing this, according to the company, would then set up a conflict of interest for the dealers since properly advertising the benefits of an electric car would disparage the gas-powered vehicles, creating a disincentive to dealership EV sales.[138] Musk himself further contended that dealers would have a disincentive to sell electric vehicles because they require less maintenance and therefore would reduce after-sales service revenue, a large profit center for most dealerships.[105]

Intellectual property

In January 2021, Tesla filed a lawsuit against Alex Khatilov alleging that the former employee stole company information by downloading files related to its Warp Drive software to his personal Dropbox account.[366] Khatilov denies the allegation that he was acting as a "willful and malicious thief" and attributes his actions to an accidental data transfer.[367] The case was settled in August 2021 through mediation.[368]

Tesla has sued former employees in the past for similar actions, including those who left to work for a rival such as XPeng and Zoox;[369] for example, Guangzhi Cao, a Tesla engineer, was accused of uploading Tesla Autopilot source code to his iCloud account;[370] Tesla and Cao settled in April 2021, in which Cao was ordered to monetarily compensate Tesla.[371]

Misappropriation

In 2018, a class action was filed against Musk and the members of Tesla's board alleging they breached their fiduciary duties by approving Musk's stock-based compensation plan.[356] Musk received the first portion of his stock options payout, worth more than $700 million in May 2020.[372]

In July 2023, Tesla board members returned $735 million to the company to settle a claim from a 2020 lawsuit alleging misappropriation of 11 million stock options granted to Elon Musk, Kimbal Musk, Larry Ellison, and others from 2017 to 2020.[373]

Environmental violations

In 2019, The United States Environmental Protection Agency fined Tesla for hazardous waste violations that occurred in 2017.[374] In June 2019, Tesla began negotiating penalties for 19 environmental violations from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District;[375] the violations took place around Tesla Fremont's paint shop, where there had been at least four fires between 2014 and 2019.[376] Environmental violations and permit deviations at Tesla's Fremont Factory increased from 2018 to 2019 with the production ramp of the Model 3.[377]

In June 2018, Tesla employee Martin Tripp leaked information that Tesla was scrapping or reworking up to 40% of its raw materials at the Nevada Gigafactory.[378] After Tesla fired him for the leak, Tripp filed a lawsuit and claimed Tesla's security team gave police a false tip that he was planning a mass shooting at the Nevada factory.[379][319] The court ruled in Tesla's favor on September 17, 2020.[380][381]

Property damage

In August 2019, Walmart filed a multi-million-dollar lawsuit against Tesla, claiming that Tesla's "negligent installation and maintenance" of solar panels caused roof fires at seven Walmart stores dating back to 2012.[382] Walmart reached a settlement with Tesla in November 2019; the terms of the settlement were not disclosed.[383]

In May 2021, a Norwegian judge found Tesla guilty of throttling charging speed through a 2019 over-the-air software update, awarding each of the 30 customers who were part of the lawsuit 136,000 Norwegian kroner ($16,000).[384]

Racism

Tesla has faced numerous complaints regarding workplace harassment and racial discrimination,[385][386] with one former Tesla worker who attempted to sue the employer describing it as "a hotbed of racist behavior".[387] As of December 2021, three percent of leadership at the company are African American.[388] A former black worker described the work environment at Tesla's Buffalo plant as a "very racist place".[389] Tesla and SpaceX's treatment of Juneteenth in 2020 also came under fire.[390] Approximately 100 former employees have submitted signed statements alleging that Tesla discriminates specifically against African Americans and "allows a racist environment in its factories."[391] According to the state's Department of Fair Employment and Housing, the Fremont factory is a racially segregated place where Black employees claim they are given the most menial[392] and physically demanding work.[393] The accusations of racism culminated in February 2022 with the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing suing Tesla for "discriminating against its Black workers."[394]

In July 2021, former employee Melvin Berry received $1 million in his discrimination case in arbitration against Tesla after he claimed he was referred to by the n-word and forced to work longer hours at the Fremont plant.[395]

In October 2021, a jury verdict in the Owen Diaz vs. Tesla trial awarded the plaintiff $137 million in damages after he had faced racial harassment at Tesla's Fremont facility during 2015–2016.[396][397] In a blog, Tesla stressed that Diaz was never "really" a Tesla worker, and that most utterings of the n-word were expressed in a friendly manner.[398][399] In April 2022, federal judge William Orrick upheld the jury finding of Tesla's liability but reduced the total damage down to $15 million.[400] Diaz was given a two-week deadline to decide if he would collect the damages. In June 2022, Diaz announced that he would be rejecting the $15 million award, opening the door for a new trial.[401] In April 2023, Diaz was awarded $3.2 million in the new trial.[402]

Few of these cases against Tesla ever make it to trial as most employees are made to sign arbitration agreements.[403] Employees are afterwards required to resolve such disputes out of court, and behind closed doors.

COVID-19 pandemic

Tesla's initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States has been the subject of considerable criticism. Musk had sought to exempt the Tesla Fremont factory in Alameda County, California from the government's stay-at-home orders. In an earnings call in April, he was heard calling the public health orders "fascist".[404] He had also called the public's response to the pandemic "dumb" and had said online that there would be zero cases by April.[405] In May 2020, while Alameda County officials were negotiating with the company to reopen the Fremont Factory on the 18th, Musk defied local government orders by restarting production on the 11th.[406][407][74] Tesla also sued Alameda County, questioning the legality of the orders, but backed down after the Fremont Factory was given approval to reopen.[408][409] In June 2020, Tesla published a detailed plan for bringing employees back to work and keeping them safe,[410] however some employees still expressed concern for their health.[411]

In May 2020, Musk told workers that they could stay home if they felt uncomfortable coming back to work.[412] But in June, Tesla fired an employee who criticized the company for taking inadequate safety measures to protect workers from the coronavirus at the Fremont Factory.[413] Three more employees at Tesla's Fremont Factory claimed they were fired for staying home out of fear of catching COVID-19. This was subsequently denied by Tesla, which even stated that the employees were still on the payroll.[414] COVID-19 cases at the factory grew from 10 in May 2020 to 125 in December 2020, with about 450 total cases in that time period out of the approximately 10,000 workers at the plant (4.5%).[404][415]

In China, Tesla had what one executive described as "not a green light from the government to get back to work – but a flashing-sirens police escort."[416] Tesla enjoyed special treatment and strong government support in China, including tax breaks, cheap financing, and assistance in building its Giga Shanghai factory at breakneck speeds.[416] Musk has praised China's way of doing things, a controversial stance due to deteriorating U.S.–Chinese relations, China's ongoing persecution of Uyghurs, and alleged human rights abuses in Hong Kong.[416]

Criticism

Data privacy

Tesla was only the second product ever reviewed by Mozilla foundation which ticked all of their privacy concerns.[417][418]

A Tesla owner filed a lawsuit in 2023 following a Reuters report that Tesla employees shared "highly invasive videos and images recorded by customers' car cameras" with one another.[419]

Short sellers

TSLAQ is a collective of Tesla critics and short sellers who aim to "shape [the] perception [of Tesla] and move its stock."[420] In January 2020, 20% of Tesla stock was shorted, the highest at that time of any stock in the U.S. equity markets.[421] By early 2021, according to CNN, short sellers had lost $40 billion during 2020 as the stock price climbed much higher.[422] Michael Burry, a short seller portrayed in The Big Short, had shorted Tesla previously via his firm Scion Asset Management, but removed his position in October 2021.[423]

Tesla's mission

According to automotive journalist Jamie Kitman, when multiple CEOs of major automotive manufacturers approached Tesla for EV technology that Musk had claimed the company was willing to share, they instead were offered the opportunity to buy regulatory credits from Tesla. This suggested, according to Kitman, that "the company may not be as eager for the electric revolution to occur as it claims."[424]

Giga New York audit

In 2020, the New York State Comptroller released an audit of the Giga New York factory project, concluding that it presented many red flags, including lack of basic due diligence and that the factory itself produced only $0.54 in economic benefits for every $1 spent by the state.[425][426][427]

Delays

Musk has been criticized for repeated pushing out both production and release dates of products.[428][429] By one count in 2016, Musk had missed 20 projections.[430] In October 2017, Musk predicted that Model 3 production would be 5,000 units per week by December.[431] A month later, he revised that target to "sometime in March" 2018.[432] Delivery dates for the Model 3 were delayed as well.[433] Other projects like converting supercharger stations to be solar-powered have also lagged projections.[434] Musk responded in late 2018: "punctuality is not my strong suit...I never made a mass-produced car. How am I supposed to know with precision when it's gonna get done?"[435]

Vehicle product issues

Recalls

On April 20, 2017, Tesla issued a worldwide recall of 53,000 (~70%) of the 76,000 vehicles it sold in 2016 due to faulty parking brakes which could become stuck and "prevent the vehicles from moving".[436][437] On March 29, 2018, Tesla issued a worldwide recall of 123,000 Model S cars built before April 2016 due to corrosion-susceptible power steering bolts, which could fail and require the driver to use "increased force" to control the vehicle.[438]

In October 2020, Tesla initiated a recall of nearly 50,000 Model X and Y vehicles throughout China for suspension issues.[439] Soon after in November, the NHTSA announced it had opened its own investigation into 115,000 Tesla cars regarding "front suspension safety issues", citing specifically 2015–2017 Model S and 2016–2017 Model X years. Cases of the "whompy wheel" phenomenon, which also included Model X and the occasional Model 3 cars, have been documented through 2020.[440][441]

In February 2021, Tesla was required by the NHTSA to recall 135,000 Model S and Model X vehicles built from 2012 to 2018 due to using a flash memory device that was rated to last only 5 to 6 years.[442] The problem was related to touchscreen failures that could possibly affect the rear-view camera, safety systems, Autopilot and other features.[443][444] The underlying technical reason is that the car writes a large amount of syslog content to the device, wearing it out prematurely.[445]

Also in February 2021, the German Federal Motor Transport Authority (KBA) ordered Tesla to recall 12,300 Model X cars because of "body mouldings problems".[446][447]

In June 2021, Tesla recalled 5,974 electric vehicles due to worries that brake caliper bolts might become loose, which could lead to loss of tire pressure, potentially increasing the chance of a crash.[448]

On December 30, 2021, Tesla announced that they are recalling more than 475,000 US model vehicles. This included 356,309 Model 3 Tesla vehicles from 2017 to 2020 due to rear-view camera issues and a further 119,009 Tesla Model S vehicles due to potential problems with the trunk or boot. The Model S recall includes vehicles manufactured between 2014 and 2021. Around 1% of recalled Model 3s may have a defective rear-view camera, and around 14% of recalled model S' may have the defect. The recall was not linked to a contemporaneous issue regarding the Passenger Play feature, which allowed games to be played on the touchscreen while the car is in motion.[449] After an investigation was launched by the NHTSA covering 585,000 vehicles, Tesla agreed to make changes where the feature would be locked and unusable while the car is moving.[450]

In September 2022, Tesla announced that they are recalling almost 1.1 million US model vehicles because the automatic window reversal system might not react correctly after detecting an obstruction, increasing the risk of injury.[451][452] In response, Tesla announced an over-the-air software fix.[452]

In February 2023, Tesla recalled its FSD software following a recommendation from NHTSA; the recall applied to approximately 360,000 cars.[453] NHTSA found that FSD caused "unreasonable risk" when used on city streets.[454] In March 2023, about 3,500 Model Y Teslas were recalled for a bolting issue concerning the cars' second-row seats.[455]

In December 2023, following a 2-year-long investigation by the NHTSA,[456] Tesla issued a wider recall on all vehicles equipped with any version of Autosteer, including 2012–2023 Model S; 2016–2023 Model X; 2017–2023 Model 3; and 2020–2023 Model Y, covering 2,031,220 vehicles in total.[457] The NHTSA concluded that Autosteer's controls were not sufficient to prevent misuse and did not ensure that the drivers maintained "continuous and sustained responsibility for vehicle operation" and states that affected vehicles will receive an over-the-air software remedy.[457][458]

Fires

Tesla customers have reported the company as being "slow" to address how their cars can ignite.[459] In 2013, a Model S caught fire after the vehicle hit metal debris on a highway in Kent, Washington. Tesla confirmed the fire began in the battery pack and was caused by the impact of an object.[460] As a result of this and other incidents, Tesla announced its decision to extend its current vehicle warranty to cover fire damage.[461] In March 2014, the NHTSA announced that it had closed the investigation into whether the Model S was prone to catch fire, after Tesla said it would provide more protection to its battery packs.[462] All Model S cars manufactured after March 6, 2014, have had the 0.25-inch (6.4 mm) aluminum shield over the battery pack replaced with a new three-layer shield.[463] In October 2019, the NHTSA opened an investigation into possible battery defects in Tesla's Model S and X vehicles from 2012 to 2019 that could cause "non-crash" fires.[464][465][466]

Autopilot crashes

A Model S driver died in a collision with a tractor-trailer in 2016, while the vehicle was in Autopilot mode; the driver is believed to be the first person to have died in a Tesla vehicle in Autopilot.[467][468] The NHTSA investigated the accident but found no safety-related defect trend.[469] In March 2018, a driver of a Tesla Model X was killed in a crash. Investigators say that the driver of the vehicle had his car in 'self-driving' mode and was using his phone to play games when the vehicle collided with the barrier in the middle of the freeway. Through investigation, the NTSB found that the Tesla malfunctioned due to the system being confused by an exit on the freeway.[470]

According to a document released in June 2021, the NHTSA has initiated at least 30 investigations into Tesla crashes that were believed to involve the use of Autopilot, with some involving fatalities.[471][472] In early September 2021, the NHTSA updated the list with an additional fatality incident[473] and ordered Tesla to hand over all extensive data pertaining to US cars with Autopilot to determine if there is a safety defect that leads Tesla cars to collide with first-responder vehicles.[473][474][475] In late September 2021, Tesla released an over-the-air software update to detect emergency lights at night.[476] In October 2021, the NHTSA asked Tesla why it did not issue a recall when it sent out that update.[477] In June 2022, the NHTSA said it would expand its probe, extending it to 830,000 cars from all current Tesla models. The probe will be moved up from the Preliminary Evaluation level to the Engineering Analysis one. The regulator cited the reason for the expansion as the need to "explore the degree to which Autopilot and associated Tesla systems may exacerbate human factors or behavioral safety risks by undermining the effectiveness of the driver's supervision."[478]

A safety test conducted by the Dawn Project in August 2022 demonstrated that a test driver using the beta version of Full Self-Driving repeatedly hit a child-sized mannequin in its path,[479] but there has been controversy over its conclusions.[480] Several Tesla owners responded by conducting their own, independent tests using children; NHTSA released a statement warning against the practice.[481]

Software hacking

In August 2015, two researchers said they were able to take control of a Tesla Model S by hacking into the car's entertainment system.[482] The hack required the researchers to physically access the car.[483] Tesla issued a security update for the Model S the day after the exploit was announced.[484]

In September 2016, researchers at Tencent's Keen Security Lab demonstrated a remote attack on a Tesla Model S and controlled the vehicle in both Parking and Driving Mode without physical access. They were able to compromise the automotive networking bus (CAN bus) when the vehicle's web browser was used while the vehicle was connected to a malicious Wi-Fi hotspot.[485] This was the first case of a remote control exploit demonstrated on a Tesla. The vulnerability was disclosed to Tesla under their bug bounty program and patched within 10 days, before the exploit was made public.[486] Tencent also hacked the doors of a Model X in 2017.[487]

In January 2018, security researchers informed Tesla that an Amazon Web Services account of theirs could be accessed directly from the Internet and that the account had been exploited for cryptocurrency mining. Tesla responded by securing the compromised system, rewarding the security researchers financially via their bug bounty program, and stating that the compromise did not violate customer privacy, nor vehicle safety or security.[488][489] Later in 2019, Tesla awarded a car and $375,000 to ethical hackers during a Pwn2Own Model 3 hacking event.[490]

In June 2022, Martin Herfurt, a security researcher in Austria, discovered that changes made to make Tesla vehicles easier to start with NFC cards also allowed for pairing new keys to the vehicle, allowing an attacker to enroll their own keys to a vehicle.[491]

Phantom braking

In February 2022, Tesla drivers have reported a surge in "phantom braking" events when using Tesla Autopilot which coincides with the automaker's removal of radar as a supplemental sensor in May 2021.[492] In response, NHTSA has opened an investigation.[493]

In May 2023, German business newspaper Handelsblatt published a series of articles based on a trove of internal Tesla data submitted to them from informants.[494] The 100 gigabytes of data "contain[ed] over 1,000 accident reports involving phantom braking or unintended acceleration" as well as complaints about Tesla Autopilot.[495] Dutch authorities responded by saying they were investigating the company for possible data privacy violations.[496]

Driving range performance

Tesla has received thousands of complaints from owners that the driving ranges of their vehicles did not meet the ranges advertised by Tesla or the projections of in-dash range meters. When service centers were overwhelmed with appointments to take care of these issues, Tesla established a diversion team to cancel as many appointments as possible. Customers were told that remote diagnostics had determined there was no problem and their appointments were canceled. The company has been fined by South Korean regulators for its exaggerated range estimates.[497]

Vehicle sales

In 2022, Tesla ranked as the world's bestselling battery electric passenger car manufacturer, with a market share of 18%.[498] Tesla reported 2022 vehicle deliveries of 1,313,851 units, up 40% from 2021.[499][500] In March 2023, Tesla produced its 4 millionth car.[501]

Production and sales by quarter

- Model S

- Model X

- Model S/X

- Model 3

- Model 3/Y