| Naqiʾa | |

|---|---|

| Woman of the Palace[lower-alpha 1] Mother of the King[lower-alpha 2] | |

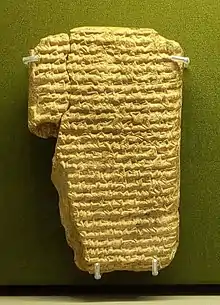

Naqiʾa depicted in a contemporary relief | |

| Born | Before c. 728 BC |

| Died | After 669 BC |

| Spouse | Sennacherib |

| Issue | Esarhaddon Šadditu (?) |

| West Semitic (possibly Aramaic) | Naqīʾa |

| Akkadian | Zakūtu |

Naqiʾa or Naqia[3][4][5] (Akkadian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Naqīʾa,[6] also known as Zakūtu (

Naqīʾa,[6] also known as Zakūtu (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ),[6][7] was a wife of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) and the mother of his son and successor Esarhaddon (r. 681–669). Naqiʾa is the best documented woman in the history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[8] and she reached an unprecedented level of prominence and public visibility;[9] she was perhaps the most influential woman in Assyrian history.[8] She is one of the few ancient Assyrian women to be depicted in artwork, to commission her own building projects, and to be granted laudatory epithets in letters by courtiers. She is also the only known ancient Assyrian figure other than kings to write and issue a treaty.

),[6][7] was a wife of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) and the mother of his son and successor Esarhaddon (r. 681–669). Naqiʾa is the best documented woman in the history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[8] and she reached an unprecedented level of prominence and public visibility;[9] she was perhaps the most influential woman in Assyrian history.[8] She is one of the few ancient Assyrian women to be depicted in artwork, to commission her own building projects, and to be granted laudatory epithets in letters by courtiers. She is also the only known ancient Assyrian figure other than kings to write and issue a treaty.

Naqiʾa must have been married to Sennacherib before he became king (705) since she gave birth to his son Esarhaddon c. 713. Whether she ever held the position of queen is debated; Assyrian kings had multiple wives but the evidence suggests that only one of them could be the queen at any one given time. Sennacherib is known to have had another queen, Tašmētu-šarrat. Naqiʾa might have become queen late in Sennacherib's reign. She is referred to as the "queen of Sennacherib" in documents from the reign of her son. In 684, Sennacherib, perhaps influenced by Naqiʾa, designated Esarhaddon as his crown prince despite having older sons.

During the reign of her son, Naqiʾa reached her most prominent position, bearing the title ummi šari (lit. 'Mother of the King'). Under Esarhaddon, Naqiʾa secured ownership of several estates throughout the empire and grew enormously wealthy, perhaps wealthier than Esarhaddon's own queen Ešarra-ḫammat. Naqiʾa might have governed her own set of territories surrounding the Babylonian city of Lahira. The last known attestation of Naqiʾa is from 669, in the months after Esarhaddon's death. After her son's death, Naqiʾa wrote a treaty which forced the royal family, aristocracy and all of Assyria to swear loyalty to her grandson Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631). After this, Naqiʾa appears to have retired from public life.

Name and origin

Though nothing certain can be said of her origins, Naqiʾa having two names could point to her originating outside of Assyria proper, possibly in Babylonia or in the Levant.[7] The name Naqīʾa is originally of Aramaic,[10][7] or at the very least West Semitic,[6] origin while Zakūtu is Akkadian.[7] The name Zakūtu, used only sometimes,[11] was probably adopted when she became associated with the Assyrian royal family; both names have the same meaning, interpreted as "purity",[12] "pure"[4] or "the pure one".[13] Naqiʾa is known to have had a sister, Abirami (Abi-rāmi[14] or Abi-rāmu),[15] attested as purchasing land in the city of Baruri in 674 BC.[11][14]

Biography

Reign of Sennacherib

Given the age at which she gave birth to Esarhaddon, Naqiʾa cannot have been born later than c. 728.[16] Naqiʾa was one of the consorts of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705–681),[17] with the marriage taking place by the late 8th century due to the birth of their son in c. 713.[18] This was before Sennacherib's accession to the throne, when he was still crown prince under his father Sargon II.[17] Except for Esarhaddon, it is unknown which of Sennacherib's many children were also the children of Naqiʾa.[19] It is probable that Naqiʾa was also the mother of Sennacherib's only daughter known by name, Šadditu,[1] since Šadditu retained a prominent position under Esarhaddon.[19] Naqiʾa was not the mother of Sennacherib's elder sons, such as Arda-Mulissu.[1]

It is possible that Naqiʾa gained influence already in Sennacherib's reign; in 684 she may have been responsible for the king dismissing Arda-Mulissu as heir and instead proclaiming their son Esarhaddon as crown prince.[1][7][13] Despite growing reports that Esarhaddon suffered from various illnesses, Sennacherib at no point changed the succession after Esarhaddon's appointment as crown prince, also perhaps due to Naqiʾa's influence. She is recorded as employing divination and astrology to bolster Sennacherib's opinion of Esarhaddon.[20] Throughout her life, Naqiʾa seems to have maintained a close relationship with prophets active in the city of Arbela.[21]

Though often identified as a queen of Sennacherib,[1][4][6] it is not clear whether Naqiʾa held that position in Sennacherib's lifetime.[6] The chief issue is that Naqiʾa is known to have been associated with Sennacherib before he became king and with Esarhaddon throughout his subsequent reign (681–669), but Sennacherib is known to also have been married to another woman, Tašmētu-šarrat, who is securely attested with the title of queen.[17] The general assumption among researchers is that while kings could have multiple wives, only one of them was at any given time recognized as the queen since administrative documents always use the title without qualification (implying that there was no ambiguity).[22][23]

Naqiʾa is referred to as Sennacherib's queen (mí.é.gal) in multiple documents, but all of them, perhaps with a single exception, were written in Esarhaddon's reign,[1] meaning that she might have been bestowed the title retroactively by her son.[23] The single possible exception is a single bead with a fragmentary inscription that calls her "mí.é.gal of Sennacherib" and then breaks off; it is possible that it was written in Sennacherib's reign.[1] Another possibility is that Naqiʾa achieved the status of queen only late in Sennacherib's reign.[23] Tašmētu-šarrat is not mentioned in any documents from Esarhaddon's reign.[24] Perhaps the promotion of Naqiʾa's son as crown prince means that she was queen around 684 and that Tašmētu-šarrat (otherwise attested only securely in c. 694)[17] was dead at that point in time.[1] After Esarhaddon became crown prince, Sennacherib granted some tax-exempt lands to Naqiʾa. In the document describing the grant, she is however titled only as the "mother of the crown prince".[11]

Reign of Esarhaddon

Naqiʾa's authority grew in the reign of her son; early on she built a palace for him in Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, and made an inscription commemorating the construction.[18] Constructing palaces was an unusual activity for a queen to engage in, usually done only by kings. The inscription documenting the project is bombastic and clearly takes inspiration from those of the kings.[8] In most sources from Esarhaddon's time,[18] Naqiʾa is referred simply to as the queen mother (ummi šari, lit. 'Mother of the King'). Naqiʾa retained this title in the reign of Esarhaddon's son (and her grandson) Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631), despite then no longer being the mother of the reigning king.[2] In terms of surviving sources she was by far the most prominent queen mother in Assyrian history; most known occurrences of the title are from her lifetime.[18]

As queen mother, the basic structure of Naqiʾa's household was similar to that of the queen and other officials. In addition to Nineveh, Naqiʾa probably had residencies in other cities, including some in Babylonia.[18] Naqiʾa appears to have had significant estates in the Babylonian city of Lahira (Laḫiru), which she perhaps governed herself;[13][14] a 678 document describes the city as part of "the queen mother's domain".[14] All queens also appear to have had large holdings in the western city of Harran. Some mentions exist of a statue of Naqiʾa being built in the city of Gadisê, near Harran.[14]

Naqiʾa was likely very wealthy, perhaps even wealthier than Esarhaddon's queen Ešarra-ḫammat. Naqiʾa is recorded to have made numerous donations to temples, to have provided the royal palace with horses from her estates and to have employed a large and extensive staff. It is clear that she held an exceptional position; in letters addressed to her numerous flattering epithets, such as "able like Adapa", are used. A legal document from Esarhaddon's reign claims that "the verdict of the mother of the king, my lord, is as final as that of the gods".[18] Such statements are highly unusual given that they usually only applied to kings.[25] Numerous letters from courtiers refer to the health of Naqiʾa. Her security appears to have been a matter of great concern as one document containing a query to the sun-god Shamash asks whether a person who might be appointed to her guard would guard Naqiʾa "like his own self.[26]

Though letters to Naqiʾa were mostly about religious affairs, some concern politics.[18] It is possible that she partook in Esarhaddon's rebuilding project of Babylon, destroyed by his father.[13] Perhaps Naqiʾa's prominence resulted from Esarhaddon's own tumultuous accession, when he had to fight a civil war against his brother Arda-Mulissu.[26] In 2014, Philippe Clancier speculated that Naqiʾa might have commanded armies during this civil war, though no Assyrian text describes her doing so. The only Assyrian queen, and woman overall, confidently known to have partaken in military campaigns is the earlier Shammuramat. If Naqiʾa did lead armies against Arda-Mulissu, omitting this from the records would not be surprising since all battlefield victories were normally ascribed to the Assyrian king personally whether or not the king was at the battle.[10] The civil war is thought to have been the catalyst of Esarhaddon's later paranoia and distrust of his servants, vassals and family members.[27] Although highly distrustful of his male relatives, Esarhaddon seems to not have been paranoid in regards to his female relatives. During his reign his queen Ešarra-ḫammat, his mother Naqiʾa and his daughter Šērūʾa-ēṭirat all wielded considerably more influence and political power than women during most earlier parts of Assyrian history,[28] though they never occupied any formal political positions.[9] A explanation for the reverence accorded to Naqiʾa by officials of the empire is that the people might have partly credited the empire's successes in Esarhaddon's reign to her.[20] Though capable and energetic,[8] Esarhaddon was chronically ill for the duration of his reign and Naqiʾa might have been believed to have had some sort of magical influence, connected to the association between the Assyrian queen and the goddess Ishtar, that kept the empire victorious.[20]

Later life

The last evidence of Naqiʾa is from around the time of Ashurbanipal's accession, at the end of 669, when she forced the royal family, aristocracy and all of Assyria to swear loyalty to her grandson.[26] The royal treaty forced on the people by Naqiʾa, dubbed the Zakutu Treaty by modern historians, is a remarkable document as the only text of its kind written by someone other than the king.[9][29] Why Naqiʾa, and not Ashurbanipal, was the one to implement the treaty is not known. Some aspects of the treaty, for instance its brevity, indicate that it was created relatively hastily after Esarhaddon's death in 669.[29] The Zakutu Treaty reads:[29]

Treaty of Zakutu, queen of Sennacherib, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, (grandmother of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria) with Shamash-shum-ukin, his equal brother, with Shamash-metu-uballit and the rest of his brothers, with the king's relatives, with the officials and the governors, the bearded and the eunuchs, the courtiers, the exempted people, and everyone who enters the palace, with the people of Assyria, small and great: Anyone who (concludes) this treaty which Zakutu, the queen dowager, has imposed on all the people of Assyria on behalf of Ashurbanipal, her favorite grandson, anyone who should [...] lie and carry out a deceitful or evil plan or revolt against Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; in your hearts plot evil intrigue (or) speak slander against Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; in your hearts contrive (or) plan an evil mission (or) wicked proposal for rebellion (and) uprising against Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; [...] or conspire with another for the murder of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord: May [...] Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, Mercury, [...] (And if) from this day on you (hear) an evil (plan) of conspiracy (and) rebellion against Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord, you shall come and report to Zakutu, his (grand)mother and Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear of a (plot) to kill or destroy Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord, you shall come and report to Zakutu, his (grand)mother and Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear of evil intrigue being contrived against Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord, you shall speak (of it) in the presence of Zakutu, his (grand) mother and Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear and know that there are men who agitate or conspire among you – whether bearded men or eunuchs, whether his brothers or royal relatives or your brothers or your friends or anyone in the whole country – should you hear or know, you shall seize and kill them and bring them to Zakūtu, his (grand) mother and Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, your lord.[30]

After Ashurbanipal became king without incident, Naqiʾa appears to have retired from public life[9] since there is no further evidence of her acting publicly again.[29] Sebastian Fink believes Naqiʾa died shortly after Ashurbanipal's accession.[8] According to Gregory D. Cook, Naqiʾa was probably dead by the time of Ashurbanipal's Sack of Thebes in 663.[16] Jack Finegan on the other hand believed that Naqiʾa was alive by the time of the civil war between Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin in 652–648 and that she during this conflict again tried to support Ashurbanipal's right to rule.[13]

Naqiʾa's career resulted in her achieving, for a woman of her time, an unprecedented level of prominence and public visibility.[9] She is the best documented, and perhaps most influential, woman of the Neo-Assyrian period.[8] Naqiʾa stands apart from nearly all other Assyrian queens, who are often rarely mentioned by name in surviving texts. She is the only royal woman, other than Ashurbanipal's queen Libbāli-šarrat, known to have been depicted in royal artwork.[31] In a relief depicting Naqiʾa and Esarhaddon, she is depicted seemingly nearly as his equal and as doing the same religious gesture as the king. She is also depicted wearing a "mural crown", a royal crown with features of a castle wall, also included in the artwork of Libbāli-šarrat.[32]

Legacy

In later Greco-Roman literary tradition, two great queens of Assyria were remembered: Semiramis (based on the earlier queen Shammuramat) and Nitocris. It is possible that the figure of Nitocris, said to have lived five generations after Semiramis and to have conducted building projects in Babylon, was based on Naqiʾa.[13][5] The legend of building work in Babylon could relate to her lands in Babylonia, the possibility that she partook in Esarhaddon's projects in the city,[13] or perhaps to the palace she built for her son in Nineveh early in his reign.[33] The palace at Nineveh could also have served as inspiration since the ancient Greeks sometimes erroneously equated Nineveh and Babylon.[34]

It is possible that some portions of the Semiramis legend were based on Naqiʾa, rather than Shammuramat.[5] In particular, one of the legendary tales of Semiramis describes the queen as founding Babylon. While there are no obvious connections between the historical Shammuramat and Babylon,[35] it is, as mentioned, possible to draw connections to Naqiʾa and building works in the city or the surrounding region.[34]

Characterizations of Naqiʾa vary among modern historians. Some, such as Sarah C. Melville have viewed her as an unselfish mother, who worked to help her son during his reign, whereas others, such as Zafrira Ben-Barak, have viewed her as a politically ambitious woman who exploited every opportunity she could to advance her personal position.[26]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frahm 2014, p. 191.

- 1 2 Kertai 2013, p. 120.

- ↑ Cook 2017, p. 895.

- 1 2 3 Gansell 2018, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Dalley 2005, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Teppo 2005, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elayi 2018, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fink 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Melville 2012.

- 1 2 Clancier 2014, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Tetlow 2004, p. 288.

- ↑ Nemet-Nejat 2014, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Finegan 1979, Assyrian Empire.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joannès 2016, p. 31.

- ↑ Teppo 2005, p. 34.

- 1 2 Cook 2017, p. 902.

- 1 2 3 4 Kertai 2013, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Teppo 2005, p. 37.

- 1 2 Elayi 2018, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Cook 2017, p. 903.

- ↑ Nissinen 2017, p. 320.

- ↑ Kertai 2013, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 Elayi 2018, p. 15.

- ↑ Frahm 2014, p. 192.

- ↑ Solvang 2003, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 Teppo 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ Radner 2003, p. 166.

- ↑ Radner 2003, p. 168.

- 1 2 3 4 Melville 2014, p. 231.

- ↑ Melville 2014, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Cook 2017, p. 896.

- ↑ Pinnock 2018, p. 734.

- ↑ Dalley 2013, p. 124.

- 1 2 Dalley 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ Dalley 2005, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Clancier, Philippe (2014). "Warlike men and invisible women: how scribes in the Ancient Near East represented warfare". Clio. 39 (39): 17–34. JSTOR 26238711.

- Cook, Gregory D. (2017). "Naqia and Nineveh in Nahum: Ambiguity and the Prostitute Queen". Journal of Biblical Literature. 136 (4): 895–904. doi:10.15699/jbl.1364.2017.198627. JSTOR 10.15699/jbl.1364.2017.198627.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2005). "Semiramis in History and Legend: a Case Study in Interpretation of an Assyrian Historical Tradition, with Observations on Archetypes in Ancient Historiography, on Euhemerism before Euhemerus, and on the So-called Greek Ethnographie Style". In S. Gruen, Erich (ed.). Cultural Borrowings and Ethnic Appropriations in Antiquity. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-08735-4.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: An Elusive World Wonder Traced. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5.

- Elayi, Josette (2018). Sennacherib, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 978-0884143178.

- Finegan, Jack (2018) [1979]. Archaeological History Of The Ancient Middle East. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-88029-120-0.

- Fink, Sebastian (2020). "Invisible Mesopotamian royal women?". In Carney, Elizabeth D. & Müller, Sabine (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World. London: Routledge. pp. 137–148. doi:10.4324/9780429434105-15. ISBN 978-0429434105. S2CID 224979097.

- Frahm, Eckart (2014). "Family Matters: Psychohistorical Reflections on Sennacherib and His Times". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Gansell, Amy Rebecca (2018). "Dressing the Neo-Assyrian Queen in Identity and Ideology: Elements and Ensembles from the Royal Tombs at Nimrud". American Journal of Archaeology. 122 (1): 65–100. doi:10.3764/aja.122.1.0065. JSTOR 10.3764/aja.122.1.0065. S2CID 194770386.

- Joannès, Francis (2016). "Women and Palaces in the Neo-Assyrian Period". Orient. 51: 29–46. doi:10.5356/orient.51.29. S2CID 189033552.

- Kertai, David (2013). "The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Altorientalische Forschungen. 40 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1524/aof.2013.0006. S2CID 163392326.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2012). "Zakutu (Naqi'a)". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. London: Wiley-Blackwell. OCLC 785860275.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2014). "Women in Neo-Assyrian texts". In Chavalas, Mark W. (ed.). Women in the Ancient Near East: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44855-0.

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen (2014). "Women in Neo-Assyrian Inscriptions: Neo-Assyrian Oracles". In Chavalas, Mark W. (ed.). Women in the Ancient Near East: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44855-0.

- Nissinen, Martti (2017). Ancient Prophecy: Near Eastern, Biblical, and Greek Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880855-8.

- Pinnock, Frances (2018). "A city of gold for the queen: some thoughts about the mural crown of Assyrian queens". In Cavalieri, Marco & Boschetti, Cristina (eds.). Mvlta per Ægvora: Il polisemico significato della moderna della moderna ricerca archeologica. Omaggio a Sara Santoro. Vol. II. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain. ISBN 978-2-87558-691-9.

- Radner, Karen (2003). "The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BC". ISIMU: Revista sobre Oriente Próximo y Egipto en la antigüedad. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. 6: 165–183.

- Solvang, Elna K. (2003). A Woman's Place is in the House: Royal Women of Judah and their Involvement in the House of David. London: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 0-8264-6213-8.

- Teppo, Saana (2005). Women and their Agency in the Neo-Assyrian Empire (PDF) (Thesis). University of Helsinki.

- Tetlow, Elisabeth Meier (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1628-4.