Neolithic architecture refers to structures encompassing housing and shelter from approximately 10,000 to 2,000 BC, the Neolithic period. In southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) and from there into the east and west. Early Neolithic structures and buildings can be found in southeast Anatolia, Syria, and Iraq by 8,000 BC with agriculture societies first appearing in southeast Europe by 6,500 BC, and central Europe by ca. 5,500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros (Cris), Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča.

Architectural advances are an important part of the Neolithic period (10,000-2000 BC), during which some of the major innovations of human history occurred. The domestication of plants and animals, for example, led to both new economics and a new relationship between people and the world, an increase in community size and permanence, a massive development of material culture, and new social and ritual solutions to enable people to live together in these communities. New styles of individual structures and their combination into settlements provided the buildings required for the new lifestyle and economy, and were also an essential element of change.[1]

Housing

The interior of a reconstructed Çatalhöyük house

The interior of a reconstructed Çatalhöyük house Pottery miniature of a Cucuteni-Trypillian house

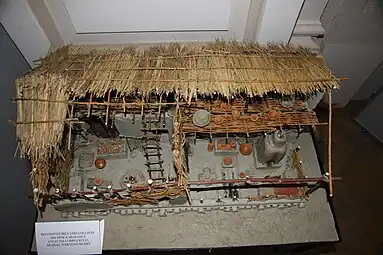

Pottery miniature of a Cucuteni-Trypillian house Miniature of a regular Cucuteni-Trypillian house, full of ceramic vessels

Miniature of a regular Cucuteni-Trypillian house, full of ceramic vessels Reconstruction of a settlement of the Linear Pottery culture, 5th millennium BC, in the Archaeological Museum of Kelheim (Lower Bavaria, Germany)

Reconstruction of a settlement of the Linear Pottery culture, 5th millennium BC, in the Archaeological Museum of Kelheim (Lower Bavaria, Germany)

The Neolithic people in the Levant, Anatolia, Syria, northern Mesopotamia and central Asia were great builders, utilising mud-brick to construct houses and villages. At Çatalhöyük, houses were plastered and painted with elaborate scenes of humans and animals.

In Europe, the Neolithic long house with a timber frame, pitched, thatched roof, and walls finished in wattle and daub could be very large, presumably housing a whole extended family. Villages might comprise only a few such houses.

Neolithic pile dwellings have been excavated in Sweden (Alvastra pile dwelling) and in the circum-Alpine area, with remains being found at the Mondsee and Attersee lakes in Upper Austria. Early archaeologists like Ferdinand Keller thought they formed artificial islands, much like the Scottish crannogs, but today it is clear that the majority of settlements was located on the shores of lakes and were only inundated later on. Reconstructed pile dwellings are shown in open-air museums in Unteruhldingen and Zürich (Pfahlbauland).

In Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine, Neolithic settlements included wattle-and-daub structures with thatched roofs and floors made of logs covered in clay.[2] This is also when the burdei pit-house (below-ground) style of house construction was developed, which was still used by Romanians and Ukrainians until the 20th century.

Neolithic settlements and "cities" include:

- Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, ca. 9,000 BC

- Tell es-Sultan (Jericho) in the Levant, Neolithic from around 8,350 BC, arising from the earlier Epipaleolithic Natufian culture

- Nevali Cori in Turkey, ca. 8,000 BC

- Çatalhöyük in Turkey, 7,500 BC

- Mehrgarh in Pakistan, 7,000 BC

- Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, the Orkney Islands, Scotland, from 3,500 BC

- over 3,000 settlements of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, some with populations up to 15,000 residents, flourished in present-day Romania, Moldova and Ukraine from 5,400 to 2,800 BC.

Tombs and ritual monuments

Dolmen de Coste-Rouge in Soumont (France)

Dolmen de Coste-Rouge in Soumont (France) Megalithic tomb in Mane Braz (Brittany)

Megalithic tomb in Mane Braz (Brittany)

Elaborate tombs for the dead were also built. These tombs are particularly numerous in Ireland, where there are many thousand still in existence. Neolithic people in the British Isles built long barrows and chamber tombs for their dead and causewayed camps, henges and cursus monuments.

Megalithic architecture

Megaliths found in Europe and the Mediterranean were also erected in the Neolithic period. These monuments include megalithic tombs, temples and several structures of unknown function. Tomb architecture is normally easily distinguished by the presence of human remains that had originally been buried, often with recognizable intent. Other structures may have had a mixed use, now often characterised as religious, ritual, astronomical or political. The modern distinction between various architectural functions with which we are familiar today, now makes it difficult for us to think of some megalithic structures as multi-purpose socio-cultural centre points. Such structures would have served a mixture of socio-economic, ideological, political functions and indeed aesthetic ideals.

The megalithic structures of Ġgantija, Tarxien, Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Ta' Ħaġrat, Skorba and smaller satellite buildings on Malta and Gozo, first appearing in their current form around 3600 BC, represent one of the earliest examples of a fully developed architectural statement in which aesthetics, location, design and engineering fused into free-standing monuments. Stonehenge, the other well-known building from the Neolithic would later, 2600 and 2400 BC for the sarsen stones, and perhaps 3000 BC for the blue stones, be transformed into the form that we know so well. At its height Neolithic architecture marked geographic space; their durable monumentality embodied a past, perhaps made up of memories and remembrance.

In the Central Mediterranean, Malta also became home of a subterranean skeuomorphised form of architecture around 3600 BC. At the Ħal-Saflieni Hypogeum, the inhabitants of Malta carved out an underground burial complex in which surface architectural elements were used to embellish a series of chambers and entrances. It is at the Neolithic Ħal-Saflieni Hypogeum that the earliest known skeuomorphism first occurred in the world. This architectural device served to define the aesthetics of the underworld in terms that well known in the larger megaliths. On Malta and Gozo, surface and subterranean architecture defined two worlds, which later, in the Greek world, would manifest themselves in the myth of Hades and the world of the living. In Malta, therefore, we encounter Neolithic architecture which is demonstrably not purely functional, but which was conceptual in design and purpose.

Other structures

Early Neolithic water wells from the Linear Pottery culture have been found in central Germany near Leipzig. These structures are built in timber with complicated woodworking joints at the edges and are dated between 5,200 and 5,100 BCE.[3]

The world's oldest known engineered roadway, the Sweet Track in England, also dates from this time.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Richard Rogers, Philip Gumuchdjian, Denna Jones, and other people (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. p. 148 & 149. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gheorghiu, D. (2010). The technology of building in Chalcolithic southeastern Europe, pp. 95–100. In Gheorghiu, D. (ed.), Neolithic and Chalcolithic Architecture in Eurasia: Building Techniques and Spatial Organisation. Proceedings of the XV UISPP World Congress (Lisbon, 4–9 September 2006) / Actes du XV Congrès Mondial (Lisbonne, 4–9 Septembre 2006), Vol 48, Session C35, BAR International Series 2097, Archaeopress, Oxford.

- ↑ Early Neolithic Water Wells Reveal the World's Oldest Wood Architecture Tegel W, Elburg R, Hakelberg D, Stäuble H, Büntgen U (2012) Early Neolithic Water Wells Reveal the World's Oldest Wood Architecture. PLoS ONE 7(12): e51374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051374

- ↑ "The Sweet Track". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-02-24.