Sintered silicon nitride ceramic | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Silicon nitride | |

| Other names

Trisilicon tetranitride,[1] Nierite | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.620 |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | Silicon+nitride |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Si3N4 | |

| Molar mass | 140.283 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | grey, odorless powder[2] |

| Density | 3.17 g/cm3[2] |

| Melting point | 1,900 °C (3,450 °F; 2,170 K)[2] (decomposes) |

| Insoluble[2] | |

Refractive index (nD) |

2.016[3] |

| Thermochemistry[4] | |

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) |

101.3 J·mol−1·K−1 |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−743.5 kJ·mol−1 |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−642.6 kJ·mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

[5] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

silicon carbide, silicon dioxide |

Other cations |

boron nitride, carbon nitride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Silicon nitride is a chemical compound of the elements silicon and nitrogen. Si

3N

4 (Trisilicon tetranitride) is the most thermodynamically stable and commercially important of the silicon nitrides,[6] and the term ″Silicon nitride″ commonly refers to this specific composition. It is a white, high-melting-point solid that is relatively chemically inert, being attacked by dilute HF and hot H

3PO

4. It is very hard (8.5 on the mohs scale). It has a high thermal stability with strong optical nonlinearities for all-optical applications.[7]

Production

Silicon nitride is prepared by heating powdered silicon between 1300 °C and 1400 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere:

- 3 Si + 2 N

2 → Si

3N

4

The silicon sample weight increases progressively due to the chemical combination of silicon and nitrogen. Without an iron catalyst, the reaction is complete after several hours (~7), when no further weight increase due to nitrogen absorption (per gram of silicon) is detected.

In addition to Si

3N

4, several other silicon nitride phases (with chemical formulas corresponding to varying degrees of nitridation/Si oxidation state) have been reported in the literature. These include the gaseous disilicon mononitride (Si

2N), silicon mononitride (SiN) and silicon sesquinitride (Si

2N

3), each of which are stoichiometric phases. As with other refractories, the products obtained in these high-temperature syntheses depends on the reaction conditions (e.g. time, temperature, and starting materials including the reactants and container materials), as well as the mode of purification. However, the existence of the sesquinitride has since come into question.[8]

It can also be prepared by diimide route:[9]

- SiCl

4 + 6 NH

3 → Si(NH)

2 + 4 NH

4Cl(s) at 0 °C - 3 Si(NH)

2 → Si

3N

4 + N

2 + 3 H

2(g) at 1000 °C

Carbothermal reduction of silicon dioxide in a nitrogen atmosphere at 1400–1450 °C has also been examined:[9]

- 3 SiO

2 + 6 C + 2 N

2 → Si

3N

4 + 6 CO

The nitridation of silicon powder was developed in the 1950s, following the "rediscovery" of silicon nitride and was the first large-scale method for powder production. However, use of low-purity raw silicon caused contamination of silicon nitride by silicates and iron. The diimide decomposition results in amorphous silicon nitride, which needs further annealing under nitrogen at 1400–1500 °C to convert it to a crystalline powder; this is now the second-most-important route for commercial production. The carbothermal reduction was the earliest used method for silicon nitride production and is now considered as the most-cost-effective industrial route to high-purity silicon nitride powder.[9]

Film deposition

Electronic-grade silicon nitride films are formed using chemical vapor deposition (CVD), or one of its variants, such as plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD):[9][10]

- 3 SiH

4(g) + 4 NH

3(g) → Si

3N

4(s) + 12 H

2(g) at 750–850°C[11] - 3 SiCl

4(g) + 4 NH

3(g) → Si

3N

4(s) + 12 HCl(g) - 3 SiCl

2H

2(g) + 4 NH

3(g) → Si

3N

4(s) + 6 HCl(g) + 6 H

2(g)

For deposition of silicon nitride layers on semiconductor (usually silicon) substrates, two methods are used:[10]

- Low pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) technology, which works at rather high temperature and is done either in a vertical or in a horizontal tube furnace,[12] or

- Plasma-enchanced atomic layer chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) technology, which works at rather low temperature (≤ 250 °C) and vacuum conditions.[13] Examples include (bisdiethylamino)silane as silicon precursor and plasma of N2 as reactant.[13]

Since the lattice constants of silicon nitride and silicon are different, tension or stress can occur, depending on the deposition process. Especially when using PECVD technology this tension can be reduced by adjusting deposition parameters.[14]

Silicon nitride nanowires can also be produced by sol-gel method using carbothermal reduction followed by nitridation of silica gel, which contains ultrafine carbon particles. The particles can be produced by decomposition of dextrose in the temperature range 1200–1350 °C. The possible synthesis reactions are:[15]

- SiO

2(s) + C(s) → SiO(g) + CO(g) and - 3 SiO(g) + 2 N

2(g) + 3 CO(g) → Si

3N

4(s) + 3 CO

2(g) or - 3 SiO(g) + 2 N

2(g) + 3 C(s) → Si

3N

4(s) + 3 CO(g).

Processing

Silicon nitride is difficult to produce as a bulk material—it cannot be heated over 1850 °C, which is well below its melting point, due to dissociation to silicon and nitrogen. Therefore, application of conventional hot press sintering techniques is problematic. Bonding of silicon nitride powders can be achieved at lower temperatures through adding materials called sintering aids or "binders", which commonly induce a degree of liquid phase sintering.[16] A cleaner alternative is to use spark plasma sintering, where heating is conducted very rapidly (seconds) by passing pulses of electric current through the compacted powder. Dense silicon nitride compacts have been obtained by this techniques at temperatures 1500–1700 °C.[17][18]

Crystal structure and properties

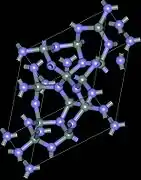

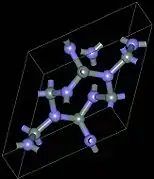

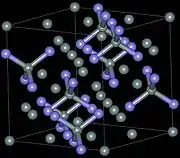

There exist three crystallographic structures of silicon nitride (Si

3N

4), designated as α, β and γ phases.[19] The α and β phases are the most common forms of Si

3N

4, and can be produced under normal pressure condition. The γ phase can only be synthesized under high pressures and temperatures and has a hardness of 35 GPa.[20][21]

The α- and β-Si

3N

4 have trigonal (Pearson symbol hP28, space group P31c, No. 159) and hexagonal (hP14, P63, No. 173) structures, respectively, which are built up by corner-sharing SiN

4 tetrahedra. They can be regarded as consisting of layers of silicon and nitrogen atoms in the sequence ABAB... or ABCDABCD... in β-Si

3N

4 and α-Si

3N

4, respectively. The AB layer is the same in the α and β phases, and the CD layer in the α phase is related to AB by a c-glide plane. The Si

3N

4 tetrahedra in β-Si

3N

4 are interconnected in such a way that tunnels are formed, running parallel with the c axis of the unit cell. Due to the c-glide plane that relates AB to CD, the α structure contains cavities instead of tunnels. The cubic γ-Si

3N

4 is often designated as c modification in the literature, in analogy with the cubic modification of boron nitride (c-BN). It has a spinel-type structure in which two silicon atoms each coordinate six nitrogen atoms octahedrally, and one silicon atom coordinates four nitrogen atoms tetrahedrally.[22]

The longer stacking sequence results in the α-phase having higher hardness than the β-phase. However, the α-phase is chemically unstable compared with the β-phase. At high temperatures when a liquid phase is present, the α-phase always transforms into the β-phase. Therefore, β-Si

3N

4 is the major form used in Si

3N

4 ceramics.[23] Abnormal grain growth may occur in doped β-Si

3N

4, whereby abnormally large elongated grains form in a matrix of finer equiaxed grains and can serve as a technique to enhance fracture toughness in this material by crack bridging.[24] Abnormal grain growth in doped silicon nitride arises due to additive-enhanced diffusion and results in composite microstructures, which can also be considered as “in-situ composites” or “self-reinforced materials.[25]

In addition to the crystalline polymorphs of silicon nitride, glassy amorphous materials may be formed as the pyrolysis products of preceramic polymers, most often containing varying amounts of residual carbon (hence they are more appropriately considered as silicon carbonitrides). Specifically, polycarbosilazane can be readily converted to an amorphous form of silicon carbonitride based material upon pyrolysis, with valuable implications in the processing of silicon nitride materials through processing techniques more commonly used for polymers.[26]

Applications

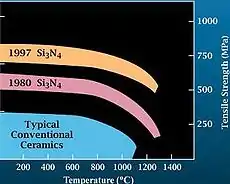

In general, the main issue with applications of silicon nitride has not been technical performance, but cost. As the cost has come down, the number of production applications is accelerating.[27]

Automobile industry

One of the major applications of sintered silicon nitride is in automobile industry as a material for engine parts. Those include, in diesel engines, glowplugs for faster start-up; precombustion chambers (swirl chambers) for lower emissions, faster start-up and lower noise; turbocharger for reduced engine lag and emissions. In spark-ignition engines, silicon nitride is used for rocker arm pads for lower wear, turbocharger turbines for lower inertia and less engine lag, and in exhaust gas control valves for increased acceleration. As examples of production levels, there is an estimated more than 300,000 sintered silicon nitride turbochargers made annually.[9][16][27]

Bearings

Silicon nitride bearings are both full ceramic bearings and ceramic hybrid bearings with balls in ceramics and races in steel. Silicon nitride ceramics have good shock resistance compared to other ceramics. Therefore, ball bearings made of silicon nitride ceramic are used in performance bearings. A representative example is use of silicon nitride bearings in the main engines of the NASA's Space Shuttle.[28][29]

Since silicon nitride ball bearings are harder than metal, this reduces contact with the bearing track. This results in 80% less friction, three to ten times longer lifetime, 80% higher speed, 60% less weight, the ability to operate with lubrication starvation, higher corrosion resistance and higher operation temperature, as compared to traditional metal bearings.[27] Silicon nitride balls weigh 79% less than tungsten carbide balls. Silicon nitride ball bearings can be found in high end automotive bearings, industrial bearings, wind turbines, motorsports, bicycles, rollerblades and skateboards. Silicon nitride bearings are especially useful in applications where corrosion or electric or magnetic fields prohibit the use of metals, for example, in tidal flow meters, where seawater attack is a problem, or in electric field seekers.[16]

Si3N4 was first demonstrated as a superior bearing in 1972 but did not reach production until nearly 1990 because of challenges associated with reducing the cost.

Since 1990, the cost has been reduced substantially as production volume has increased. Although Si

3N

4 bearings are still two to five times more expensive than the best steel bearings, their superior performance and life are justifying rapid adoption. Around 15–20 million Si

3N

4 bearing balls were produced in the U.S. in 1996 for machine tools and many other applications. Growth is estimated at 40% per year, but could be even higher if ceramic bearings are selected for consumer applications such as in-line skates and computer disk drives.[27]

NASA testing says ceramic-hybrid bearings exhibit much lower fatigue (wear) life than standard all-steel bearings.[30]

High-temperature material

Silicon nitride has long been used in high-temperature applications. In particular, it was identified as one of the few monolithic ceramic materials capable of surviving the severe thermal shock and thermal gradients generated in hydrogen/oxygen rocket engines. To demonstrate this capability in a complex configuration, NASA scientists used advanced rapid prototyping technology to fabricate a one-inch-diameter, single-piece combustion chamber/nozzle (thruster) component. The thruster was hot-fire tested with hydrogen/oxygen propellant and survived five cycles including a 5-minute cycle to a 1320 °C material temperature.[31]

In 2010 silicon nitride was used as the main material in the thrusters of the JAXA space probe Akatsuki.[32]

Silicon nitride was used for the "microshutters" developed for the Near Infrared Spectrograph aboard the James Webb Space Telescope. According to NASA: The "operating temperature is cryogenic so the device has to be able to operate at extremely cold temperatures. Another challenge was developing shutters that would be able to: open and close repeatedly without fatigue; open individually; and open wide enough to meet the science requirements of the instrument. Silicon nitride was chosen for use in the microshutters, because of its high strength and resistance to fatigue." This microshutter system allows the instrument to observe and analyze up to 100 celestial objects simultaneously.[33]

Medical

Silicon nitride has many orthopedic applications.[34][35] The material is also an alternative to PEEK (polyether ether ketone) and titanium, which are used for spinal fusion devices (with latter being relatively expensive).[36][37] It is silicon nitride's hydrophilic, microtextured surface that contributes to the material's strength, durability and reliability compared to PEEK and titanium.[35][36][38] Certain compositions of this material exhibit anti-bacterial,[39] anti-fungal,[40] or anti-viral properties.[41]

Metal working and cutting

The first major application of Si

3N

4 was abrasive and cutting tools. Bulk, monolithic silicon nitride is used as a material for cutting tools, due to its hardness, thermal stability, and resistance to wear. It is especially recommended for high speed machining of cast iron. Hot hardness, fracture toughness and thermal shock resistance mean that sintered silicon nitride can cut cast iron, hard steel and nickel based alloys with surface speeds up to 25 times quicker than those obtained with conventional materials such as tungsten carbide.[16] The use of Si

3N

4 cutting tools has had a dramatic effect on manufacturing output. For example, face milling of gray cast iron with silicon nitride inserts doubled the cutting speed, increased tool life from one part to six parts per edge, and reduced the average cost of inserts by 50%, as compared to traditional tungsten carbide tools.[9][27]

Electronics

_process.svg.png.webp)

Silicon nitride is often used as an insulator and chemical barrier in manufacturing integrated circuits, to electrically isolate different structures or as an etch mask in bulk micromachining. As a passivation layer for microchips, it is superior to silicon dioxide, as it is a significantly better diffusion barrier against water molecules and sodium ions, two major sources of corrosion and instability in microelectronics. It is also used as a dielectric between polysilicon layers in capacitors in analog chips.[42]

Silicon nitride deposited by LPCVD contains up to 8% hydrogen. It also experiences strong tensile stress, which may crack films thicker than 200 nm. However, it has higher resistivity and dielectric strength than most insulators commonly available in microfabrication (1016 Ω·cm and 10 MV/cm, respectively).[10]

Not only silicon nitride, but also various ternary compounds of silicon, nitrogen and hydrogen (SiNxHy) are used as insulating layers. They are plasma deposited using the following reactions:[10]

- 2 SiH

4(g) + N

2(g) → 2 SiNH(s) + 3 H

2(g) - SiH

4(g) + NH

3(g) → SiNH(s) + 3 H

2(g)

These SiNH films have much less tensile stress, but worse electrical properties (resistivity 106 to 1015 Ω·cm, and dielectric strength 1 to 5 MV/cm),[10][43] and are thermally stable to high temperatures under specific physical conditions. Silicon nitride is also used in the xerographic process as one of the layers of the photo drum.[44] Silicon nitride is also used as an ignition source for domestic gas appliances.[45] Because of its good elastic properties, silicon nitride, along with silicon and silicon oxide, is the most popular material for cantilevers — the sensing elements of atomic force microscopes.[46]

Solar cells

Solar cells are often coated with an anti-reflective coating. Silicon nitride can be used for this, and it is possible to adjust its index of refraction by varying the parameters of the deposition process.[47][48]

Photonic integrated circuits

Photonic integrated circuits can be produced with various materials, also called material platforms. Silicon nitride is one of those material platforms, next to, for example, Silicon Photonics and Indium Phosphide. Silicon Nitride photonic integrated circuits have a broad spectral coverage and features low light losses. This makes them highly suited to detectors, spectrometers, biosensors, and quantum computers. The lowest propagation losses reported in SiN (0.1 dB/cm down to 0.1 dB/m) have been achieved by LioniX International’s TriPleX waveguides.[49]

History

The first preparation was reported in 1857 by Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville and Friedrich Wöhler.[50] In their method, silicon was heated in a crucible placed inside another crucible packed with carbon to reduce permeation of oxygen to the inner crucible. They reported a product they termed silicon nitride but without specifying its chemical composition. Paul Schuetzenberger first reported a product with the composition of the tetranitride, Si

3N

4, in 1879 that was obtained by heating silicon with brasque (a paste made by mixing charcoal, coal, or coke with clay which is then used to line crucibles) in a blast furnace. In 1910, Ludwig Weiss and Theodor Engelhardt heated silicon under pure nitrogen to produce Si

3N

4.[51] E. Friederich and L. Sittig made Si3N4 in 1925 via carbothermal reduction under nitrogen, that is, by heating silica, carbon, and nitrogen at 1250–1300 °C.

Silicon nitride remained merely a chemical curiosity for decades before it was used in commercial applications. From 1948 to 1952, the Carborundum Company, Niagara Falls, New York, applied for several patents on the manufacture and application of silicon nitride.[9] By 1958 Haynes (Union Carbide) silicon nitride was in commercial production for thermocouple tubes, rocket nozzles, and boats and crucibles for melting metals. British work on silicon nitride, started in 1953, was aimed at high-temperature parts of gas turbines and resulted in the development of reaction-bonded silicon nitride and hot-pressed silicon nitride. In 1971, the Advanced Research Project Agency of the US Department of Defense placed a US$17 million contract with Ford and Westinghouse for two ceramic gas turbines.[52]

Even though the properties of silicon nitride were well known, its natural occurrence was discovered only in the 1990s, as tiny inclusions (about 2 μm × 0.5 μm in size) in meteorites. The mineral was named nierite after a pioneer of mass spectrometry, Alfred O. C. Nier.[53] This mineral may have been detected earlier, again exclusively in meteorites, by Soviet geologists.[54]

References

- ↑ "Silicon nitride (compound)". PubChem. Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.88. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ↑ Refractive index database. refractiveindex.info

- ↑ CRC handbook of chemistry and physics : a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. William M. Haynes, David R. Lide, Thomas J. Bruno (2016-2017, 97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5428-6. OCLC 930681942.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ ITEM # SI-501, SILICON NITRIDE POWDER MSDS Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. metal-powders-compounds.micronmetals.com

- ↑ Mellor, Joseph William (1947). A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry. Vol. 8. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 115–7. OCLC 493750289.

- ↑ López-Suárez, A.; Torres-Torres, C.; Rangel-Rojo, R.; Reyes-Esqueda, J. A.; Santana, G.; Alonso, J. C.; Ortiz, A.; Oliver, A. (2009-06-08). "Modification of the nonlinear optical absorption and optical Kerr response exhibited by nc-Si embedded in a silicon-nitride film". Optics Express. 17 (12): 10056–10068. Bibcode:2009OExpr..1710056L. doi:10.1364/OE.17.010056. ISSN 1094-4087. PMID 19506657.

- ↑ Carlson, O. N. (1990). "The N-Si (Nitrogen-Silicon) system". Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams. 11 (6): 569–573. doi:10.1007/BF02841719.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Riley, Frank L. (2004). "Silicon Nitride and Related Materials". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 83 (2): 245–265. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01182.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nishi, Yoshio; Doering, Robert (2000). Handbook of semiconductor manufacturing technology. CRC Press. pp. 324–325. ISBN 978-0-8247-8783-7.

- ↑ Morgan, D. V.; Board, K. (1991). An Introduction To Semiconductor Microtechnology (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 978-0471924784.

- ↑ "Crystec Technology Trading GmbH, Comparison of vertical and horizontal tube furnaces in the semiconductor industry". crystec.com. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- 1 2 Shen, Jie; Roozeboom, Fred; Mameli, Alfredo (2023). "Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma-Enhanced Spatial Atomic Layer Deposition of Silicon Nitride at Low Temperature". Atomic Layer Deposition. doi:10.15212/aldj-2023-1000. S2CID 257304966. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ↑ "Crystec Technology Trading GmbH, deposition of silicon nitride layers". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Ghosh Chaudhuri, Mahua; Dey, Rajib; Mitra, Manoj K.; Das, Gopes C.; Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2008). "A novel method for synthesis of α-Si3N4 nanowires by sol-gel route". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1): 5002. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a5002G. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/015002. PMC 5099808. PMID 27877939.

- 1 2 3 4 Sorrell, Chris (2001-02-06). "Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) Properties and Applications". AZo Journal of Materials. ISSN 1833-122X. OCLC 939116350.

- ↑ Nishimura, T.; Xu, X.; Kimoto, K.; Hirosaki, N.; Tanaka, H. (2007). "Fabrication of silicon nitride nanoceramics—Powder preparation and sintering: A review". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 8 (7–8): 635–643. Bibcode:2007STAdM...8..635N. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2007.08.006.

- ↑ Peng, p. 38

- ↑ "Crystal structures of Si3N4". hardmaterials.de. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Jiang, J. Z.; Kragh, F.; Frost, D. J.; Ståhl, K.; Lindelov, H. (2001). "Hardness and thermal stability of cubic silicon nitride". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 13 (22): L515. Bibcode:2001JPCM...13L.515J. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/13/22/111. S2CID 250763667.

- ↑ "Properties of gamma-Si3N4". Archived from the original on July 15, 2006. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Peng, pp. 1-3

- ↑ Zhu, Xinwen; Sakka, Yoshio (2008). "Textured silicon nitride: Processing and anisotropic properties". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (3): 3001. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9c3001Z. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/033001. PMC 5099652. PMID 27877995.

- ↑ Abnormal grain growth Journal of Crystal growth

- ↑ Effect of Grain Growth of B-Silicon Nitride on Strength, Weibull Modulus, and Fracture Toughness Journal of the American Ceramic Society

- ↑ Wang, Xifan; Schmidt, Franziska; Hanaor, Dorian; Kamm, Paul H.; Li, Shuang; Gurlo, Aleksander (2019). "Additive manufacturing of ceramics from preceramic polymers: A versatile stereolithographic approach assisted by thiol-ene click chemistry". Additive Manufacturing. 27: 80–90. arXiv:1905.02060. Bibcode:2019arXiv190502060W. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2019.02.012. S2CID 104470679.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richerson, David W.; Freita, Douglas W. "Ceramic Industry". Opportunities for Advanced Ceramics to Meet the Needs of the Industries of the Future. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. hdl:2027/coo.31924090750534. OCLC 692247038.

- ↑ "Ceramic Balls Increase Shuttle Engine Bearing Life". NASA. Archived from the original on 2004-10-24. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ "Space Shuttle Main Engine Enhancements". NASA. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Zaretsky, Erwin V.; Vlcek, Brian L.; Hendricks, Robert C. (1 April 2005). "Effect of Silicon Nitride Balls and Rollers on Rolling Bearing Life".

- ↑ Eckel, Andrew J. (1999). "Silicon Nitride Rocket Thrusters Test Fired Successfully". NASA. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009.

- ↑ Orbit Control Maneuver Result of the Venus Climate Orbiter 'AKATSUKI'. JAXA (2010-07-06)

- ↑ James Webb Space Telescope / Goddard Space Flight Center > Innovations > Microshutters / Nasa (2020-06-25).

- ↑ Olofsson, Johanna; Grehk, T. Mikael; Berlind, Torun; Persson, Cecilia; Jacobson, Staffan; Engqvist, Håkan (2012). "Evaluation of silicon nitride as a wear resistant and resorbable alternative for total hip joint replacement". Biomatter. 2 (2): 94–102. doi:10.4161/biom.20710. PMC 3549862. PMID 23507807.

- 1 2 Mazzocchi, M; Bellosi, A (2008). "On the possibility of silicon nitride as a ceramic for structural orthopaedic implants. Part I: Processing, microstructure, mechanical properties, cytotoxicity". Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 19 (8): 2881–7. doi:10.1007/s10856-008-3417-2. PMID 18347952. S2CID 10388233.

- 1 2 Webster, T.J.; Patel, A.A.; Rahaman, M.N.; Sonny Bal, B. (2012). "Anti-infective and osteointegration properties of silicon nitride, poly(ether ether ketone), and titanium implants". Acta Biomaterialia. 8 (12): 4447–54. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2012.07.038. PMID 22863905.

- ↑ Anderson, MC; Olsen, R (2010). "Bone ingrowth into porous silicon nitride". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 92 (4): 1598–605. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32498. PMID 19437439.

- ↑ Arafat, Ahmed; Schroën, Karin; De Smet, Louis C. P. M.; Sudhölter, Ernst J. R.; Zuilhof, Han (2004). "Tailor-Made Functionalization of Silicon Nitride Surfaces". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (28): 8600–1. doi:10.1021/ja0483746. PMID 15250682.

- ↑ Pezzotti, Giuseppe; Marin, Elia; Adachi, Tetsuya; Lerussi, Federica; Rondinella, Alfredo; Boschetto, Francesco; Zhu, Wenliang; Kitajima, Takashi; Inada, Kosuke; McEntire, Bryan J.; Bock, Ryan M. (2018-04-24). "Incorporating Si3 N4 into PEEK to Produce Antibacterial, Osteocondutive, and Radiolucent Spinal Implants". Macromolecular Bioscience. 18 (6): 1800033. doi:10.1002/mabi.201800033. ISSN 1616-5187. PMID 29687593.

- ↑ McEntire, B., Bock, R., & Bal, B.S. U.S Application. No. 20200079651. 2020.

- ↑ Pezzotti, Giuseppe; Ohgitani, Eriko; Shin-Ya, Masaharu; Adachi, Tetsuya; Marin, Elia; Boschetto, Francesco; Zhu, Wenliang; Mazda, Osam (2020-06-20). "Rapid Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by Silicon Nitride, Copper, and Aluminum Nitride". doi:10.1101/2020.06.19.159970. S2CID 220044677. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Pierson, Hugh O. (1992). Handbook of chemical vapor deposition (CVD). William Andrew. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-8155-1300-1.

- ↑ Sze, Simon M.; Lee, Ming-Kwei (2012). Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology (3 ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-118-13983-7.

- ↑ Duke, Charles B.; Noolandi, Jaan; Thieret, Tracy (2002). "The surface science of xerography" (PDF). Surface Science. 500 (1–3): 1005–1023. Bibcode:2002SurSc.500.1005D. doi:10.1016/S0039-6028(01)01527-8.

- ↑ Levinson, L. M. et al. (17 April 2001) "Ignition system for a gas appliance" U.S. Patent 6,217,312

- ↑ Ohring, M. (2002). The materials science of thin films: deposition and structure. Academic Press. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-12-524975-1.

- ↑ Rajinder Sharma (Jul 2, 2019). "Effect of obliquity of incident light on the performance of silicon solar cells". Heliyon. 5 (7): e01965. Bibcode:2019Heliy...501965S. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01965. PMC 6611928. PMID 31317080.

- ↑ Rajinder Sharma (May 2018). "Silicon nitride as antireflection coating to enhance the conversion efficiency of silicon solar cells". Turkish Journal of Physics. 42 (4): 350–355. doi:10.3906/fiz-1801-28. S2CID 139899251.

- ↑ Roeloffzen, Chris G. H.; Hoekman, Marcel; Klein, Edwin J.; Wevers, Lennart S.; Timens, Roelof Bernardus; Marchenko, Denys; Geskus, Dimitri; Dekker, Ronald; Alippi, Andrea; Grootjans, Robert; van Rees, Albert; Oldenbeuving, Ruud M.; Epping, Jorn P.; Heideman, Rene G.; Worhoff, Kerstin (July 2018). "Low-Loss Si3N4 TriPleX Optical Waveguides: Technology and Applications Overview". IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics. 24 (4): 1–21. Bibcode:2018IJSTQ..2493945R. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2018.2793945. ISSN 1077-260X. S2CID 3431441.

- ↑ "Ueber das Stickstoffsilicium". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 104 (2): 256. 1857. doi:10.1002/jlac.18571040224.

- ↑ Weiss, L. & Engelhardt, T (1910). "Über die Stickstoffverbindungen des Siliciums". Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 65 (1): 38–104. doi:10.1002/zaac.19090650107.

- ↑ Carter, C. Barry & Norton, M. Grant (2007). Ceramic Materials: Science and Engineering. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-387-46270-7.

- ↑ Lee, M. R.; Russell, S. S.; Arden, J. W.; Pillinger, C. T. (1995). "Nierite (Si3N4), a new mineral from ordinary and enstatite chondrites". Meteoritics. 30 (4): 387. Bibcode:1995Metic..30..387L. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1995.tb01142.x.

- ↑ "Nierite". Mindat. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

Cited sources

- Peng, Hong (2004). Spark Plasma Sintering of Si3N4-based Ceramics: Sintering mechanism-Tailoring microstructure-Evaluating properties (PhD thesis). Stockholm University. ISBN 978-91-7265-834-9.