In statistics, the hypergeometric distribution is the discrete probability distribution generated by picking colored balls at random from an urn without replacement.

Various generalizations to this distribution exist for cases where the picking of colored balls is biased so that balls of one color are more likely to be picked than balls of another color.

This can be illustrated by the following example. Assume that an opinion poll is conducted by calling random telephone numbers. Unemployed people are more likely to be home and answer the phone than employed people are. Therefore, unemployed respondents are likely to be over-represented in the sample. The probability distribution of employed versus unemployed respondents in a sample of n respondents can be described as a noncentral hypergeometric distribution.

The description of biased urn models is complicated by the fact that there is more than one noncentral hypergeometric distribution. Which distribution one gets depends on whether items (e.g., colored balls) are sampled one by one in a manner in which there is competition between the items or they are sampled independently of one another. The name noncentral hypergeometric distribution has been used for both of these cases. The use of the same name for two different distributions came about because they were studied by two different groups of scientists with hardly any contact with each other.

Agner Fog (2007, 2008) suggested that the best way to avoid confusion is to use the name Wallenius' noncentral hypergeometric distribution for the distribution of a biased urn model in which a predetermined number of items are drawn one by one in a competitive manner and to use the name Fisher's noncentral hypergeometric distribution for one in which items are drawn independently of each other, so that the total number of items drawn is known only after the experiment. The names refer to Kenneth Ted Wallenius and R. A. Fisher, who were the first to describe the respective distributions.

Fisher's noncentral hypergeometric distribution had previously been given the name extended hypergeometric distribution, but this name is rarely used in the scientific literature, except in handbooks that need to distinguish between the two distributions.

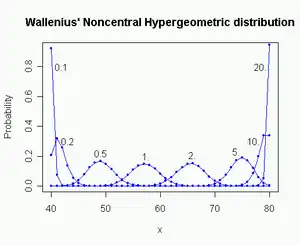

Wallenius' noncentral hypergeometric distribution

Wallenius' distribution can be explained as follows. Assume that an urn contains red balls and white balls, totalling balls. balls are drawn at random from the urn one by one without replacement. Each red ball has the weight , and each white ball has the weight . We assume that the probability of taking a particular ball is proportional to its weight. The physical property that determines the odds may be something else than weight, such as size or slipperiness or some other factor, but it is convenient to use the word weight for the odds parameter.

The probability that the first ball picked is red is equal to the weight fraction of red balls:

The probability that the second ball picked is red depends on whether the first ball was red or white. If the first ball was red then the above formula is used with reduced by one. If the first ball was white then the above formula is used with reduced by one.

The important fact that distinguishes Wallenius' distribution is that there is competition between the balls. The probability that a particular ball is taken in a particular draw depends not only on its own weight, but also on the total weight of the competing balls that remain in the urn at that moment. And the weight of the competing balls depends on the outcomes of all preceding draws.

A multivariate version of Wallenius' distribution is used if there are more than two different colors.

The distribution of the balls that are not drawn is a complementary Wallenius' noncentral hypergeometric distribution.

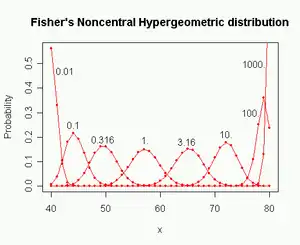

Fisher's noncentral hypergeometric distribution

In the Fisher model, the fates of the balls are independent and there is no dependence between draws. One may as well take all n balls at the same time. Each ball has no "knowledge" of what happens to the other balls. For the same reason, it is impossible to know the value of n before the experiment. If we tried to fix the value of n then we would have no way of preventing ball number n + 1 from being taken without violating the principle of independence between balls. n is therefore a random variable, and the Fisher distribution is a conditional distribution which can only be determined after the experiment when n is observed. The unconditional distribution is two independent binomials, one for each color.

Fisher's distribution can simply be defined as the conditional distribution of two or more independent binomial variates dependent upon their sum. A multivariate version of the Fisher's distribution is used if there are more than two colors of balls.

The difference between the two noncentral hypergeometric distributions

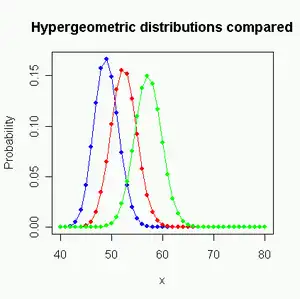

Blue: Wallenius ω = 0.5

Red: Fisher ω = 0.5

Green: Central hypergeometric ω = 1.

m1 = 80, m2 = 60, n = 100

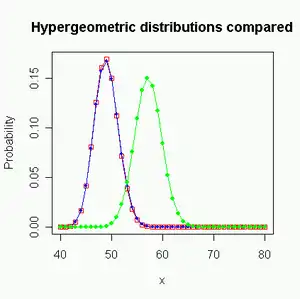

Blue: Wallenius ω = 0.5

Red: Fisher ω = 0.28

Green: Central hypergeometric ω = 1.

m1 = 80, m2 = 60, n = 100

Wallenius' and Fisher's distributions are approximately equal when the odds ratio is near 1, and n is low compared to the total number of balls, N. The difference between the two distributions becomes higher when the odds ratio is far from one and n is near N. The two distributions approximate each other better when they have the same mean than when they have the same odds (ω = 1) (see figures above).

Both distributions degenerate into the hypergeometric distribution when the odds ratio is 1, or to the binomial distribution when n = 1.

To understand why the two distributions are different, we may consider the following extreme example: An urn contains one red ball with the weight 1000, and a thousand white balls each with the weight 1. We want to calculate the probability that the red ball is not taken.

First we consider the Wallenius model. The probability that the red ball is not taken in the first draw is 1000/2000 = 1⁄2. The probability that the red ball is not taken in the second draw, under the condition that it was not taken in the first draw, is 999/1999 ≈ 1⁄2. The probability that the red ball is not taken in the third draw, under the condition that it was not taken in the first two draws, is 998/1998 ≈ 1⁄2. Continuing in this way, we can calculate that the probability of not taking the red ball in n draws is approximately 2−n as long as n is small compared to N. In other words, the probability of not taking a very heavy ball in n draws falls almost exponentially with n in Wallenius' model. The exponential function arises because the probabilities for each draw are all multiplied together.

This is not the case in Fisher's model, where balls are taken independently, and possibly simultaneously. Here the draws are independent and the probabilities are therefore not multiplied together. The probability of not taking the heavy red ball in Fisher's model is approximately 1/(n + 1). The two distributions are therefore very different in this extreme case, even though they are quite similar in less extreme cases.

The following conditions must be fulfilled for Wallenius' distribution to be applicable:

- Items are taken randomly from a finite source containing different kinds of items without replacement.

- Items are drawn one by one.

- The probability of taking a particular item at a particular draw is equal to its fraction of the total "weight" of all items that have not yet been taken at that moment. The weight of an item depends only on its kind (e.g., color).

- The total number n of items to take is fixed and independent of which items happen to be taken first.

The following conditions must be fulfilled for Fisher's distribution to be applicable:

- Items are taken randomly from a finite source containing different kinds of items without replacement.

- Items are taken independently of each other. Whether one item is taken is independent of whether another item is taken. Whether one item is taken before, after, or simultaneously with another item is irrelevant.

- The probability of taking a particular item is proportional to its "weight". The weight of an item depends only on its kind (e.g., color).

- The total number n of items that will be taken is not known before the experiment.

- n is determined after the experiment and the conditional distribution for n known is desired.

Examples

The following examples illustrate which distribution applies in different situations.

Example 1

You are catching fish in a small lake that contains a limited number of fish. There are different kinds of fish with different weights. The probability of catching a particular fish at a particular moment is proportional to its weight.

You are catching the fish one by one with a fishing rod. You have decided to catch n fish. You are determined to catch exactly n fish regardless of how long it may take. You will stop after you have caught n fish even if you can see more fish that are tempting.

This scenario will give a distribution of the types of fish caught that is equal to Wallenius' noncentral hypergeometric distribution.

Example 2

You are catching fish as in example 1, but using a big net. You set up the net one day and come back the next day to remove the net. You count how many fish you have caught and then you go home regardless of how many fish you have caught. Each fish has a probability of being ensnared that is proportional to its weight but independent of what happens to the other fish.

The total number of fish that will be caught in this scenario is not known in advance. The expected number of fish caught is therefore described by multiple binomial distributions, one for each kind of fish.

After the fish have been counted, the total number n of fish is known. The probability distribution when n is known (but the number of each type is not known yet) is Fisher's noncentral hypergeometric distribution.

Example 3

You are catching fish with a small net. It is possible that more than one fish can be caught in the net at the same time. You will use the net repeatedly until you have got at least n fish.

This scenario gives a distribution that lies between Wallenius' and Fisher's distributions. The total number of fish caught can vary if you are getting too many fish in the last catch. You may put the excess fish back into the lake, but this still does not give Wallenius' distribution. This is because you are catching multiple fish at the same time. The condition that each catch depends on all previous catches does not hold for fish that are caught simultaneously or in the same operation.

The resulting distribution will be close to Wallenius' distribution if there are few fish in the net in each catch and many casts of the net. The resulting distribution will be close to Fisher's distribution if there are many fish in the net in each catch and few casts.

Example 4

You are catching fish with a big net. Fish swim into the net randomly in a situation that resembles a Poisson process. You watch the net and take it up as soon as you have caught exactly n fish.

The resulting distribution will be close to Fisher's distribution because the fish arrive in the net independently of each other. But the fates of the fish are not completely independent because a particular fish can be saved from being caught if n other fish happen to arrive in the net before this particular fish. This is more likely to happen if the other fish are heavy than if they are light.

Example 5

You are catching fish one by one with a fishing rod as in example 1. You need a particular amount of fish in order to feed your family. You will stop when the total weight of the fish caught reaches this predetermined limit. The resulting distribution will be close to Wallenius' distribution, but not exactly equal to it because the decision to stop depends on the weight of the fish caught so far. n is therefore not known before the fishing trip.

Conclusion to the examples

These examples show that the distribution of the types of fish caught depends on the way they are caught. Many situations will give a distribution that lies somewhere between Wallenius' and Fisher's noncentral hypergeometric distributions.

A consequence of the difference between these two distributions is that one will catch more of the heavy fish, on average, by catching n fish one by one than by catching all n at the same time. In general, we can say that, in biased sampling, the odds parameter has a stronger effect in Wallenius' distribution than in Fisher's distribution, especially when n/N is high.

m1 = 80, m2 = 60, n = 100, ω = 0.1 ... 20

m1 = 80, m2 = 60, n = 100, ω = 0.01 ... 1000

See also

References

Johnson, N. L.; Kemp, A. W.; Kotz, S. (2005), Univariate Discrete Distributions, Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley and Sons.

McCullagh, P.; Nelder, J. A. (1983), Generalized Linear Models, London: Chapman and Hall.

Fog, Agner (2007), Random number theory.

Fog, Agner (2008), "Calculation Methods for Wallenius' Noncentral Hypergeometric Distribution", Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 258–273, doi:10.1080/03610910701790269, S2CID 9040568.