| Operation Summer '95 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War and the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

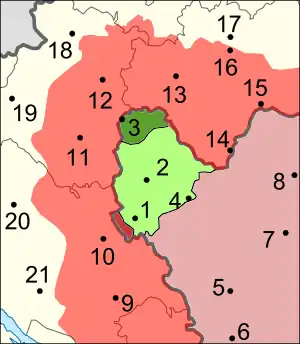

Map of Operation Summer '95 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,500 troops | 5,500 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

18 killed 155 wounded | unknown | ||||||

| 12,000–14,000 Bosnian Serb refugees | |||||||

Operation Summer '95 (Croatian: Operacija Ljeto '95) was a joint military offensive of the Croatian Army (HV) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) that took place north-west of the Livanjsko Polje, and around Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč in western Bosnia and Herzegovina. The operation was carried out between 25 and 29 July 1995, during the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War. The attacking force of 8,500 troops commanded by HV's Lieutenant General Ante Gotovina initially encountered strong resistance from the 5,500-strong Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) 2nd Krajina Corps. The HV/HVO pushed the VRS back, capturing about 1,600 square kilometres (620 square miles) of territory and consequently intercepting the Knin—Drvar road—a critical supply route of the self-declared Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The operation failed to achieve its declared primary goal of drawing VRS units away from the besieged city of Bihać, but it placed the HV in position to capture the RSK's capital Knin in Operation Storm days later.

Operation Summer '95 was launched in response to the resumption of attacks by the VRS and the RSK military on the Bihać pocket—one of six United Nations Safe Areas established in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The area was viewed as strategic to the Croatian military effort by the HV General Staff because it presented an obstacle to the supply of the RSK and it pinned down a portion of the RSK military, as well as some VRS forces that would otherwise have been redeployed. The international community feared the worst humanitarian disaster of the war to that point would occur if the RSK or the VRS overran the Bihać pocket. The United States, France and the United Kingdom were divided about the best way to protect the pocket.

Background

In August 1990, a revolution took place in Croatia; it was centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[1] and in parts of the Lika, Kordun, and Banovina regions, and settlements in eastern Croatia with significant Serb populations.[2] The areas were subsequently named the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). After declaring its intention to integrate with Serbia, the Government of Croatia declared the RSK a rebellion.[3] By March 1991, the conflict escalated into the Croatian War of Independence.[4] In June 1991, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated.[5] A three-month moratorium followed,[6] after which the decision came into effect on 8 October.[7] The RSK then initiated a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Croat civilians, and most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993. By November 1993, fewer than 400 ethnic Croats remained in the UN-protected area known as Sector South,[8] and a further 1,500 – 2,000 remained in Sector North.[9]

The Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991 because the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian Police were unable to cope with the situation. The ZNG was renamed the HV in November.[10] The establishment of the Republic of Croatia Armed Forces was hampered by a UN arms embargo introduced in September.[11] The final months of 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Battle of the Barracks,[12] the Siege of Dubrovnik,[13] and the Battle of Vukovar.[14]

In January 1992, the Sarajevo Agreement was signed by representatives of Croatia, the JNA and the UN, and fighting between the two sides was paused.[15] After a series of unsuccessful ceasefires, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed to Croatia to supervise and maintain the agreement.[16] A stalemate developed as the conflict evolved into static trench warfare, and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated.[15] Serbia continued to support the RSK,[17] but a series of HV advances restored small areas to Croatian control as the siege of Dubrovnik was lifted,[18] and Operation Maslenica resulted in minor tactical gains.[19] In response to the HV successes, the RSK intermittently attacked a number of Croatian towns and villages with artillery and missiles.[2][20][21]

As the JNA disengaged from Croatia, its personnel prepared to set up a new Bosnian Serb army; Bosnian Serbs declared the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992. Between 29 February and 1 March 1992, a referendum on independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina—which would later be cited as a pretext for the Bosnian War—was held.[22] Bosnian Serbs set up barricades in the capital Sarajevo and elsewhere on 1 March, and the next day the first fatalities of the war were recorded in Sarajevo and Doboj. In the final days of March, the Bosnian Serb army started shelling Bosanski Brod,[23] and Sarajevo was attacked on 4 April.[24]

The Bosnian Serb army—renamed the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) after the Republika Srpska state proclaimed in the Bosnian Serb-held territory—was fully integrated with the JNA. As 1992 carried on, it controlled about 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[25] This was achieved through a large-scale campaign of territorial conquest and ethnic cleansing which was backed by military and financial support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[26] The war, which originally pitted Bosnian Serbs against non-Serbs, evolved into a three-sided conflict by 1993 when the Croat–Bosniak alliance deteriorated and the Croat–Bosniak war broke out.[27] The Bosnian Croats declared a Herzeg-Bosnia state with the intent of eventually joining Croatia. This was incompatible with Bosniaks' aspirations of establishing a unitary state confronted by demands to partition the country.[26] The VRS was involved in the Croatian War of Independence in a limited capacity, through military and other aid to the RSK, occasional air raids launched from Banja Luka, and most significantly through artillery attacks against urban centres,[28][29] while the extent of territory it controlled did not change significantly until 1994.[30]

Ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Herzegovina happened on a larger scale than in the RSK, and all the major ethnic groups became victims of ethnically motivated violence.[31] The conflict produced a vast number of displaced persons. It is estimated that there were over a million refugees in areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina outside VRS control at the end of 1994, while the area's total population was about 2.2 million.[32] About 720,000 Bosniaks, 460,000 Serbs and 150,000 Croats fled the country.[33] Croatia hosted a large proportion of the Bosniak and Croat refugees; by November 1992 there were around 333,000 registered, and an estimated 100,000 unregistered, refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina in Croatia.[34] The refugees left their homes under varied circumstances.[35] The ethnic violence committed by Bosnian Serbs against civilians resulted in the greatest number of civilian victims in the Bosnian war, culminating in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre.[36]

Prelude

Areas in Croatia controlled by:

RSK, HV

Areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by:

VRS, RSK, ARBiH, APWB

1 – Bihać, 2 – Cazin, 3 – Velika Kladuša, 4 – Bosanska Krupa, 5 – Bosanski Petrovac, 6 – Drvar, 7 – Sanski Most, 8 – Prijedor, 9 – Udbina, 10 – Korenica, 11 – Slunj, 12 – Vojnić, 13 – Glina, 14 – Dvor, 15 – Kostajnica, 16 – Petrinja, 17 – Sisak, 18 – Karlovac, 19 – Ogulin, 20 – Otočac, 21 – Gospić

In November 1994, the Siege of Bihać—a battle of the Bosnian War—entered a critical stage as the VRS and the RSK came close to capturing the town. A strategic area since June 1993, Bihać had been one of six United Nations Safe Areas established in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[37] The US administration considered that if Serb forces captured the city, the war would intensify and cause the worst humanitarian disaster of the war to that point. The US, France and the UK were divided about protecting the area.[38][39] The US called for airstrikes against the VRS, but the French and the British opposed them, citing safety concerns and a desire to maintain the neutrality of French and British troops serving with the UNPROFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In turn, the US was unwilling to commit ground troops.[40] According to David Halberstam, the Europeans recognized that the US was free to propose military confrontation with the Serbs while relying on the European powers to block any such move.[41] French president François Mitterrand discouraged any military intervention, greatly helping the Serb war effort.[42] The French stance reversed after Jacques Chirac became President of France in May 1995;[43] Chirac pressured the British to adopt a more aggressive approach.[44] Denying Bihać to the Serbs was also strategically important to Croatia,[45] and Chief of the Croatian General Staff General Janko Bobetko considered that the fall of Bihać would end Croatia's war effort.[46]

In March 1994, the Washington Agreement was signed,[46] ending the Croat–Bosniak War, and providing Croatia with US military advisors from the Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI).[47] The US involvement reflected a new military strategy endorsed by Bill Clinton in February 1993.[48] Because the UN arms embargo was still in place, the MPRI was hired ostensibly to prepare the HV for participation in the NATO Partnership for Peace programme. They trained HV officers and personnel for 14 weeks from January to April 1995. It has also been speculated in several sources,[47]—including The New York Times and various Serbian media reports,[49][50]— that the MPRI may have provided doctrinal advice, scenario planning and US government satellite intelligence to Croatia.[47] MPRI,[51] American and Croatian officials have denied such claims.[52][53] In November 1994, the US unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina,[54] allowing the HV to supply itself as arms shipments flowed through Croatia.[55]

The Washington Agreement also resulted in a series of meetings between Croatian and US government and military officials held in Zagreb and Washington, D.C. On 29 November 1994, the Croatian representatives proposed to attack Serb-held territory from Livno in Bosnia and Herzegovina, to draw off a part of the force besieging Bihać and to prevent its capture by the Serbs. As the US officials gave no response to the proposal, the Croatian General Staff ordered Operation Winter '94 the same day, to be carried out by the HV and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO)—the main military force of the Bosnian Croats. Besides contributing to the defence of Bihać, the attack shifted the line of contact of the HV and the HVO closer to the RSK's supply routes.[46]

On 17 July, the RSK and the VRS militaries started Operation Sword-95, a push to capture Bihać by expanding on gains made during Operation Spider. The move provided the HV with a chance to extend their territorial gains from Operation Winter '94 by advancing from the Livno Valley. On 22 July, President of Croatia Franjo Tuđman and President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović signed the Split Agreement on mutual defence, permitting the large-scale deployment of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[56]

Order of battle

The HV and the HVO fielded Operational Group Rujani, a combined force controlled by the HV Split Corps under command of Lieutenant General Ante Gotovina. The Operational Group comprised approximately 8,500 troops arranged in two groups, and was directed against Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč. The HVO troops were deployed against Glamoč and the HV force was arrayed in the Glamoč and Bosansko Grahovo areas.[57] The defending force consisted of approximately 5,500 troops drawn from the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps, commanded by Major General Radivoje Tomanić.[57] The 2nd Krajina Corps was supported by the Vijuga battlegroup put together by the RSK 7th North Dalmatian Corps and initially deployed to the Bosansko Grahovo area as a 500-strong unit in late 1994.[58] The area was additionally reinforced following the HV's Operation Leap 2 in June 1995, using three VRS brigades deployed to Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč.[57] The VRS-deployed units were strengthened by platoons and companies transferred from seven brigades of the VRS 1st Krajina Corps and from three brigades of the VRS East Bosnian Corps.[59]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Split Corps | 7th Guards Brigade | Facing Bosansko Grahovo |

| 1 company of the 114th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 81st Guards Battalion | In the Šator Mountain area | |

| 3rd Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade | ||

| elements of the 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | ||

| Special police of the Ministry of Interior of Herzeg-Bosnia | ||

| 2nd Guards Brigade, strengthened by Gavran-2 special forces company[60] | Facing Glamoč, HVO force | |

| 3rd Guards Brigade | ||

| 60th Guards Airborne Battalion | ||

| 22nd Sabotage Detachment | ||

| 4th Guards Brigade | Held in reserve | |

| 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade | ||

| 1st Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade | ||

| Reconnaissance-Sabotage Company of the HV General Staff |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd Krajina Corps | 3rd Petrovac Light Infantry Brigade | In Bosansko Grahovo area |

| 9th Grahovo Light Infantry Brigade | ||

| RSK Vijuga battlegroup | ||

| 3rd Serbian Infantry Brigade | In Glamoč area | |

| 5th Glamoč Light Infantry Brigade | ||

| 7th Kupres-Šipovo Motorized Brigade |

Operation timeline

Operation Summer '95 started at 0500 on 25 July. The HV 7th Guards Brigade advanced north-west along the Livno–Bosansko Grahovo road towards the town of Bosansko Grahovo—the offensive's main objective. A composite company drawn from the HV 114th Infantry Brigade attacked VRS positions on the right flank of the advance. The 7th Guards Brigade managed to move forward by about 2 kilometres (1.2 miles), but had to suspend its effort as the 114th Brigade company could not defeat the VRS' entrenched defences at Marino Brdo to cover the 7th Brigade's right flank. The VRS defences were well prepared all along the front line attacked by the HV and the HVO. The Bosansko Grahovo zone was particularly well prepared for defence—fortifications, shelters and covered trenches were built to establish defence in depth, with obstacles, including minefields, in between them.[57]

The same day, the HV/HVO force advancing towards Glamoč—the offensive's secondary objective—also met strong resistance from VRS troops. The HV 81st Guards Battalion advancing south-east from the Šator Mountain to the rear of Glamoč broke forward the defences of the VRS 3rd Serbian Brigade. However, it paused its push after less than 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) because its right flank came into jeopardy when the HV and HVO units to their right were held back by the VRS's determined defence. The 1st Croatian Guards Brigade (1. hrvatski gardijski zdrug - HGZ), the Bosnian Croat special police and the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade were blocked by the VRS holding a fortified position on a mountaintop between the Šator Mountain and Glamoč. The 2nd and 3rd Guards Brigades of the HVO attacking the VRS 5th Glamoč Brigade south-west of Glamoč made little progress. The HVO 60th Guards Airborne Battalion and the 22nd Sabotage Detachment attacked in Kujača Hill south-east of Glamoč, but they too made only marginal gains.[61]

On 26 July, Gotovina deployed the 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade to the Bosansko Grahovo axis. The battalion outflanked the VRS force blocking the HV 114th Infantry Brigade composite company and attacked the VRS defences from their rear. Even though the HV could not advance more than 1 kilometre (0.62 miles), the move was sufficient to allow the HV 7th Guards Brigade to press on with their attack and push the VRS back by 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) that day, reaching within 7 kilometres (4.3 miles) from Bosansko Grahovo.[62] The imminent threat to the town sitting astride the most significant route between the Republika Srpska and the RSK capital of Knin, became an urgent matter to the RSK. The 2nd Guards Brigade of the RSK Special Units Corps was ordered to disengage from the ARBiH 5th Corps in Bihać pocket area and move to Bosansko Grahovo to defend the town. A battalion of RSK police was also ordered to bolster the defence in the area. While the police battalion declined to deploy claiming that the General Staff had no authority over the police, the RSK 2nd Guards Brigade did not reach Bosansko Grahovo in time to contribute to the defence.[63]

On the second day of the operation, the HV 1st Guards Corps and the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade outflanked the VRS mountaintop position between the Šator Mountain and Glamoč that had blocked them the previous day, allowing the HV 81st Guards Battalion to advance a further 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) and threaten to interdict a road used by the VRS to supply Glamoč from the north. To secure the high ground south of Glamoč, Gotovina released the 1st Battalion of the HV 1st Guards Brigade, supported by an anti-terrorist unit of the HV 72nd Military Police Battalion, from the reserve and used them to attack VRS positions on the 1,600-metre (5,200 ft) Vrhovi Mountain. The HVO units continued their attack towards Glamoč, achieving little progress. The HVO 2nd Guards Brigade only advanced 1-kilometre (0.62 mi) towards Glamoč. By the end of its second day, Operation Summer '95 was suffering from delays.[62]

On 27 July, Gotovina reinforced the Bosansko Grahovo axis by deploying the 4th Guards Brigade on the right flank. The brigade broke through the VRS defence in its sector, advancing about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) and arriving within 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) of Bosansko Grahovo. Advances in the Glamoč area were still being achieved slowly. The Croatian Air Force took part in the attack the same day, using two MiG-21s to conduct airstrikes designed to disrupt the road network around Glamoč, violating a no-fly zone imposed by the UN and enforced by NATO as Operation Deny Flight.[62]

The HV 4th and 7th Guards Brigades defeated the VRS defences around Bosansko Grahovo on 28 July, and the two HV brigades captured the town that day. At the same time, the HV 81st Guards Battalion and the 1st HGZ, supported by the special police, moved north of Glamoč, reaching its outskirts and cutting the main route between the town and the rest of the Bosnian Serb-held territory. After the HV threatened the VRS positions in Glamoč from their rear, defence of the town became less determined and the HVO 2nd Guards Brigade, the 60th Guards Airborne Battalion and the 22nd Sabotage Detachment broke through the VRS defences. HVO troops attacking from the south captured Glamoč on 29 July.[62]

Aftermath

Gotovina assessed the VRS's resistance to the HV and the HVO units early on during the battle as fierce,[62] while former RSK officers said that the overall resistance of the VRS and the RSK battlegroup in Bosansko Grahovo area was not great.[64] Of the attacking HV/HVO forces, 18 men were killed in action and 155 were wounded.[65] Approximately 1,600 square kilometres (620 square miles) of territory changed hands and the Knin–Drvar road, vital to resupply of the RSK, was interdicted.[66] The offensive displaced between 12,000 and 14,000 Serb refugees who fled towards Banja Luka.[67]

On 30 July, the RSK declared a state of war and the RSK President Milan Martić stated that the Croatian territorial gains would soon be reversed in cooperation with the VRS.[68] VRS Supreme Commander Colonel General Ratko Mladić visited Knin the same day, also promising to restore the territory lost that month.[69] However, the RSK military concluded that the VRS had no units in western Bosnia capable of the attack.[70] Analyses of the RSK military showed that the HV had saved the Bihać pocket for the second time and that it was preparing to attack the RSK at several points.[71] Following the offensive, the RSK authorities reported fear and panic among the population caused by the conviction that the RSK could not defend itself against the HV.[72] On 2 August, the RSK civil defence authorities ordered preparation for evacuation of the RSK,[73] and the RSK prime minister Milan Babić asked the government ministers to prepare to move to Donji Lapac.[72] Women and children started to evacuate to FR Yugoslavia, while a mobilization of the RSK military was largely completed by 3 August.[74]

Operation Summer '95 failed to achieve its goal of relieving Bihać by drawing substantial RSK forces and the VRS away from the city to contain the HV/HVO advance. The RSK 2nd Guards Brigade was ordered to move from Bihać to Bosansko Grahovo,[62] and it remained in the Knin area until the beginning of the following HV offensive, Operation Storm, on 4 August.[75] The capture of Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč by the HV and the HVO, their achievement of favourable positions to attack Knin and a large-scale HV mobilization in preparation for Operation Storm caused the RSK to shift its focus from Bihać. On 30 July, RSK civilian and military leaders, Milan Martić and General Mile Mrkšić, met with a personal representative of Secretary-General of the United Nations Yasushi Akashi and agreed upon a plan to withdraw from Bihać to prevent the expected Croatian offensive.[76] Days later, the area captured in Operation Summer '95 was used as a staging area for the 4th and the 7th Guards Brigades' advance into Knin in Operation Storm.[77] The VRS 2nd Krajina Corps tried to retake Bosansko Grahovo on the night of 11–12 August. Their advance from the direction of Drvar broke through the HV's reserve infantry left to garrison the area and reached the outskirts of the town, but was beaten back by two HV Guards battalions.[78]

Footnotes

- ↑ The New York Times & 19 August 1990

- 1 2 ICTY & 12 June 2007

- ↑ The New York Times & 2 April 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 3 March 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 26 June 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 29 June 1991

- ↑ Narodne novine & 8 October 1991

- ↑ Department of State & 31 January 1994

- ↑ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section J, points 147 & 150

- ↑ EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278

- ↑ The Independent & 10 October 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 24 September 1991

- ↑ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250

- ↑ The New York Times & 18 November 1991

- 1 2 The New York Times & 3 January 1992

- ↑ Los Angeles Times & 29 January 1992

- ↑ Thompson 2012, p. 417

- ↑ The New York Times & 15 July 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 24 January 1993

- ↑ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section K, point 161

- ↑ The New York Times & 13 September 1993

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 382

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 427

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 428

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 433

- 1 2 Bieber 2010, p. 313

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 10

- ↑ The Seattle Times & 16 July 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 17 August 1995

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 443

- ↑ Burg & Shoup 2000, pp. 171–185

- ↑ Burg & Shoup 2000, p. 171

- ↑ Burg & Shoup 2000, pp. 171–172

- ↑ The New York Times & 23 November 1992

- ↑ Burg & Shoup 2000, p. 172

- ↑ Nettelfield 2010, p. 75

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 204

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 284

- ↑ The Independent & 27 November 1994

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, pp. 285–286

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 305

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 304

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 293

- ↑ Halberstam 2003, p. 306

- ↑ Hodge 2006, p. 104

- 1 2 3 Jutarnji list & 9 December 2007

- 1 2 3 Dunigan 2011, pp. 93–94

- ↑ Woodward 2010, p. 432

- ↑ The New York Times & 13 October 2002

- ↑ RTS & 3 September 2011

- ↑ Avant 2005, p. 104

- ↑ Jutarnji list & 20 August 2010

- ↑ RFE & 20 August 2010

- ↑ Bono 2003, p. 107

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 439

- ↑ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, p. 254

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 CIA 2002, p. 365

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 300

- ↑ CIA 2002, Note 538/VII

- ↑ CIA 2002, Note 536/VII

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 365–366

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 CIA 2002, p. 366

- ↑ Sekulić 2000, p. 165

- ↑ Sekulić 2000, p. 163

- ↑ Slobodna Dalmacija & 12 July 2007

- ↑ Holjevac Turković 2009, p. 227

- ↑ UNSC & 3 August 1995, p. 2

- ↑ Marijan 2010, p. 236

- ↑ Marijan 2010, p. 279

- ↑ Marijan 2010, p. 322

- ↑ Marijan 2010, pp. 280–281

- 1 2 Marijan 2010, p. 324

- ↑ Marijan 2010, pp. 319–321

- ↑ Marijan 2010, p. 283

- ↑ Marijan 2010, p. 83

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 367

- ↑ Marijan 2010, pp. 79–82

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 379

References

- Books

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 9780160664724. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Avant, Deborah D. (2005). The Market for Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61535-8. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Bieber, Florian (2010). "Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bono, Giovanna (2003). Nato's 'Peace Enforcement' Tasks and 'Policy Communities': 1990–1999. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0944-5. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (2000). The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. New York City: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-309-1.

- Dunigan, Molly (2011). Victory for Hire: Private Security Companies' Impact on Military Effectiveness. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7459-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Halberstam, David (2003). War in a Time of Peace: Bush, Clinton and the Generals. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-6301-3. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Hodge, Carole (2006). Britain And the Balkans: 1991 Until the Present. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29889-6. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Marijan, Davor (2010). Storm (PDF). Croatian Homeland War Memorial & Documentation Centre of the Government of Croatia. ISBN 978-953-7439-25-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Nettelfield, Lara J. (2010). Courting Democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521763806.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Sekulić, Milisav (2000). Knin je pao u Beogradu [Knin was lost in Belgrade] (in Serbian). Nidda Verlag. OCLC 47749339. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2012). Nordic, Central & Southeastern Europe 2012. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-61048-891-4. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2010). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". In Vaughan Lowe; Adam Roberts; Jennifer Welsh; et al. (eds.). The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice Since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-161493-4. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- News reports

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck (29 June 1991). "Conflict in Yugoslavia; 2 Yugoslav States Agree to Suspend Secession Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Cowell, Alan (24 September 1991). "Serbs and Croats: Seeing War in Different Prisms". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Williams, Carol J. (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (15 July 1992). "The Walls and the Will of Dubrovnik". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Maass, Peter (16 July 1992). "Serb Artillery Hits Refugees – At Least 8 Die As Shells Hit Packed Stadium". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (23 November 1992). "Refugee Burden Is Impoverishing Croatian Hosts". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Sudetic, Chuck (24 January 1993). "Croats Battle Serbs for a Key Bridge Near the Adriatic". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Rebel Serbs List 50 Croatia Sites They May Raid". The New York Times. 13 September 1993. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Daly, Emma; Marshall, Andrew (27 November 1994). "Bihac fears massacre". The Independent. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bonner, Raymond (17 August 1995). "Dubrovnik Finds Hint of Deja Vu in Serbian Artillery". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Wayne, Leslie (13 October 2002). "America's For-Profit Secret Army". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Juras, Žana (12 July 2007). "Zagorec ima više odličja nego čitava kninska bojna" [Zagorec has more decorations than the entire Knin battalion]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- Vurušić, Vlado (9 December 2007). "Krešimir Ćosić: Amerikanci nam nisu dali da branimo Bihać" [Krešimir Ćosić: Americans did not let us defend Bihać]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Krasnec, Tomislav (20 August 2010). "Peter Galbraith: Srpska tužba nema šanse na sudu" [Galbraith: Serbian claim stands no chance in court]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Barbir-Mladinović, Ankica (20 August 2010). "Tvrdnje da je MPRI pomagao pripremu 'Oluje' izmišljene" [Claims that the MPRI helped prepare the 'Storm' are fabrications]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Croatian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ""Oluja" pred američkim sudom" ["Storm" before an American court] (in Serbian). Radio Television of Serbia. 3 September 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Other sources

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). Narodne novine (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia". United Nations Economic and Social Council. 17 November 1993. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Croatia human rights practices, 1993; Section 2, part d". United States Department of State. 31 January 1994. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Report of the Secretary-General submitted pursuant to Security Council Resolution 981 (1995)" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. 3 August 1995. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic - Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Holjevac Turković, Ana (November 2009). "Kraj srpske paradržavne vlasti u Hrvatskoj kroz tjedni jugoslavenski tisak" [The end of Serbian quasistate government in Croatia as seen by the weekly Yugoslav press]. Journal - Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian History, Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb. 41 (1). ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

.svg.png.webp)

_(1868-1918).svg.png.webp)