The foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire were characterized by competition with the Persian Empire to the east, Russia to the north, and Austria to the west. The control over European minorities began to collapse after 1800, with Greece being the first to break free, followed by Serbia. Egypt was lost in 1798–1805. In the early 20th century Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bulgarian Declaration of Independence soon followed. The Ottomans lost nearly all their European territory in the First Balkan War (1912–1913). The Ottoman Empire allied itself with the Central Powers in the First World War, and lost. The British successfully mobilized Arab nationalism. The Ottoman Empire thereby lost its Arab possessions, and itself soon collapsed in the early 1920s. For the period after 1923 see Foreign relations of Turkey.

Structure

The Ottoman Empire's diplomatic structure was unconventional and departed in many ways from its European counterparts. Traditionally, foreign affairs were conducted by the Reis ül-Küttab (Chief Clerk or Secretary of State) who also had other duties. In 1836, a Foreign Ministry was created.[1]

Finance

After 1600 wars were increasingly expensive and the Empire never had an efficient system of taxation.[2] The Porte relied on loans from merchants and tax farming, whereby local; elites collected taxes (and kept their share). The winner in a war acquired new territory—the local leadership usually stayed the same, only they now collected taxes for the winning government. The war's loser often paid cash reparations to the winner, who thereby recouped the cost of the war.[3]

Ambassadors

Ambassadors from the Ottoman Empire were usually appointed on a temporary and limited basis, as opposed to the resident ambassadors sent by other European nations.[4][5] The Ottomans sent 145 temporary envoys to Venice between 1384 and 1600.[6] The first resident Ottoman ambassador was not seen until Yusuf Agah Efendi was sent to London in 1793.[4][7]

Ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire began arriving shortly after the fall of Constantinople. The first was Bartelemi Marcello from Venice in 1454. The French ambassador Jean de La Forêt later arrived in 1535.[8] In 1583, the ambassadors from Venice and France would attempt unsuccessfully to block William Harborne of England from taking up residence in Istanbul. This move was repeated by Venice, France and England in trying to block Dutch ambassador Cornelius Haga in 1612.[9]

Capitulations

Capitulations were trade deals with other countries. They were a unique practice of Muslim diplomacy that was adopted by Ottoman rulers. In legal and technical terms, they were unilateral agreements made by the Sultan to a nation's merchants. These agreements were temporary, and subject to renewal by subsequent Sultans.[10][11] The origins of the capitulations comes from Harun al Rashid and his dealings with the Frankish kingdoms, but they were also used by both his successors and by the Byzantine Empire.[11]

In June 1580 came the first capitulatory agreement with England. England acquired privileges formerly limited to France and Venice. The Porte broadened English extraterritorial rights by successive renewals and expansions (in 1603, 1606, 1624, 1641, 1662, and 1675).

The Ottoman-French Treaty of 1740 marked the apogee of French influence in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century. In the following years the French had an unchallenged position in Levant trade and in transportation between Ottoman ports. Near contemporary Ottoman capitulations to European powers such as Britain and Holland (1737), the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1740), Denmark (1756), and Prussia (1761) were to offset and balance the capitulations granted to France in 1740.[12]

Military organization

Sultan Selim III in 1789 to 1807 set up the "Nizam-i Cedid" [new order] army to replace the inefficient and outmoded imperial army. The old system depended on Janissaries, who had largely lost their military effectiveness. Selim closely followed Western military forms. It would be expensive for a new army, so a new treasury ['Irad-i Cedid'] was established . The result was the Porte now had an efficient, European-trained army equipped with modern weapons. However it had fewer than 10,000 soldiers in an era when Western armies were ten to fifty times larger. Furthermore, the Sultan was upsetting the well-established traditional political powers. As a result, it was rarely used, apart from its use against Napoleon's expeditionary force at Gaza and Rosetta. The new army was dissolved by reactionary elements with the overthrow of Selim in 1807, but it became the model of the new Ottoman Army created later in the 19th century.[13][14]

1200–1500

About 1250 CE the Seljuk Turks were overwhelmed by a Mongol invasion, and they lost control of Anatolia. By 1290, Osman I established supremacy over neighboring Turkish tribes, forming the start of the Ottoman Empire. The Byzantine Empire was shrinking, but it held tenaciously onto its capital at Constantinople.[15]

The Ottoman domain became increasingly powerful and by 1400 was a crucial part of the European states system and actively played a role in their affairs, due in part to their coterminous periods of development.[16][17] In 1413–1421, Mehmed I "The Restorer" reestablished central authority in Anatolia. He expanded the Ottoman presence in Europe by the conquest of Wallachia in 1415. Venice destroyed the Turkish fleet of Gallipoli in 1416, as the Ottomans lost a naval war. In the reign of Murad II (1421–1451) there were successful naval wars with Venice and Milan. The Byzantine Empire lost virtually all its territory in Anatolia. However, the Ottomans failed in their attempted invasions of Serbia and Hungary; they besieged Constantinople. Christians from Central Europe launch the last Crusade in 1443–1444, pushing the Ottomans out of Serbia and Wallachia. This Crusade ended in defeat when the Ottomans were victorious at Varna in November 1444.[18]

Mehmed the Conqueror (1444–1446, and 1451–1481) scored the most famous victory in Ottoman history when his army finally on 29 May 1453, captured Constantinople and brought an end to the Byzantine Empire.[19][20] Towards the end of the 15th century, the Ottomans began to play a larger role in the Italian Peninsula. In 1494, both the Papacy and the Kingdom of Naples petitioned the Sultan directly for his assistance against Charles VIII of France in the First Italian War.[21] The Ottomans continue to expand, and on 28 July 1499 won their greatest naval victory over Venice, in the first battle of Lepanto.[22]

1500–1800

Ottoman policy towards Europe during the 16th century was one of disruption against the Habsburg dynasties. The Ottomans collaborated with Francis I of France and his Protestant allies in the 1530s while fighting the Habsburgs.[16] Although the French had sought an alliance with the Ottomans as early as 1531, one was not concluded until 1536. The sultan then gave the French freedom of trade throughout the empire, and plans were drawn up for an invasion of Italy from both the north and the south in 1537.[23]

Selim I

The most dramatic successes came during the short reign of Selim I (1513– 1520), as Ottoman territories were nearly doubled in size after decisive victories over the Persians and Egyptians. Selim I defeated the Mameluke army that controlled Egypt in 1517. He conquered Egypt, leaving the Mamelukes as rulers there under a Turkish governor general. Selim I moved south and took control of Mecca and the West Arabian Coast, suppressed revolts in Anatolia and Syria, and formed an alliance with Algiers. He died in 1520 as he was preparing an invasion of the island of Rhodes.[24]

- Mughals

Babur's early relations with the Ottomans were poor because Selim I provided Babur's rival, Ubaydullah Khan, with powerful matchlocks and cannons.[25] In 1507, when ordered to accept Selim I as his rightful suzerain, Babur refused and gathered Qizilbash servicemen in order to counter the forces of Ubaydullah Khan during the Battle of Ghazdewan in 1512. In 1513, Selim I reconciled with Babur (fearing that he would join the Safavids), dispatched Ustad Ali Quli and Mustafa Rumi, and many other Ottoman Turks, in order to assist Babur in his conquests; this particular assistance proved to be the basis of future Mughal-Ottoman relations.[25] From then on, he also adopted the tactic of using matchlocks and cannons in field (rather than only in sieges), which gave him an important advantage in India.[26] Babur referred to this method as the "Ottoman device" due to its previous use by the Ottomans during the Battle of Chaldiran.[27]

Suleiman the Magnificent

Selim I's son Suleiman I became known as "Suleiman the Magnificent" for his long string of military conquests[28][29] Suleiman consolidated Ottoman possessions in Europe and made the Danube the undisputed northern frontier.[30]

The decisive Ottoman victory came at the Battle of Mohács in 1526. The forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II was defeated by Suleiman's army. The result was the three-way partition of Hungary for several centuries between the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg Monarchy, and the Principality of Transylvania. Louis II was killed, thus ending the Jagiellonian dynasty in Hungary and Bohemia. Its dynastic claims passed to the House of Habsburg.

Suleiman selected cooperative local leaders in the newly acquired Wallachian, Moldavian, and Transylvanian Christian territories. The role was to keep the peace, collect taxes, and in turn were protected by the Porte. Later sultans considered replacing these tributary princes with Ottoman Muslim governors but did not do so for political, military, and financial reasons.[31] Suleiman's successes frightened the Europeans, but he failed to move north of the Danube, failed to take Vienna, failed to conquer Rome, and was unable to gain a foothold in Italy.[24] The defeats meant that the Ottoman Empire could not take advantage of the intellectual and technical advances made in Western Europe. Instead Suleiman's empire while large, failed to keep pace with the rapid advances taking place in Europe.[32] According to John Norton, additional weaknesses of Suleiman included his conscription of Christian children, maltreatment of subject peoples, and obsession with his own prestige.[33]

The Dutch allied with the Ottomans. Prince William of Orange coordinated his strategic moves with those of the Ottomans during the Turkish negotiations with Philip II of Spain in the 1570s.[16] After the Habsburgs inherited the Portuguese crown in 1580, Dutch forces attacked their Portuguese trading rivals while the Turks, supportive of the Dutch bid for independence, attacked the Habsburgs in Eastern Europe.[34]

India, China, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia

In the 16th century, there emerged travelogues of both Ottoman travelers to China and Chinese travelers to the Ottoman world.[35][36] A 16th century Chinese gazetteer, Shaanxi tongzhi, claims that there were Han-Chinese people living in a number of Ottoman controlled towns and cities such as Beirut, Tartus, Konya, and Istanbul.[37] According to the official history of the Ming dynasty, some self-proclaimed Ottoman envoys visited Beijing to pay tribute to the Ming emperor in 1524.[38][39] However, these envoys were most likely just Central and Western Asian merchants trying to conduct trade in China, since pretending to be envoys was the only way to enter the Chinese border pass.[40] One of these merchants was Ali Akbar Khitai, who visited the Ming dynasty during the reign of Emperor Zhengde. Ali Akbar later wrote the book Khitay namah and dedicated it to Sultan Suleyman.[41] The Ming Shilu also records Ottoman envoys reaching China in 1423, 1425, 1427, 1443-1445, 1459, 1525-1527, 1543-1544, 1548, 1554, 1559, 1564, 1576, 1581, and 1618.[42] Some of these missions may have been from Uzbekistan, Moghulistan, or Kara Del because the Ottomans were known in China as the rulers of five realms: Turfan, Samarqand, Mecca, Rum and Hami.[43] According to traders in the Gujarat Sultanate, the Chinese Emperor ordered all Chinese Muslims to read the khutba in the name of the Ottoman Sultan, thus preventing religious disputes from spreading across his territory.[44]

The first exchange of diplomatic missions between the Ottoman Sultans and the Muslim rulers of the Indian sub-continent dates back to the years 1481–82. Ottoman expeditions to the sultanates of Gujarat, Bijapur, and Ahmednagar were motivated by mutual anti-Portuguese sentiment; Ottoman artillery contributed to the fall of the pro-Portuguese Vijayanagara Empire. Turkish-Indian relations soured when the Mughals conquered most of India, since the Mughal Empire was a symbolic threat to the Ottoman Empire's position as the universal caliphate, despite contemplation for a Mughal-Ottoman-Uzbek alliance against Iran. After the Mughal Empire collapsed, Muslim rulers of Mysore like Tipu Sultan sought Ottoman aid in driving out the British, but the Ottomans were weakened by wars with Russia and in no position to help.

The Inner Eurasian Muslim khanates of Kazan, Khwarazm, and Bukhara were wary of Russian expansion and looked to the Ottomans for the maintenance of Silk Road contacts. With this purpose in mind, the Ottomans began to dig out a Volga-Don canal, but quickly stopped after realizing its infeasibility. Nonetheless, the Russians agreed to grant Central Asian Muslim pilgrims safe passage into Ottoman territories after the First Russo-Turkish War.[45] In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the Uzbeks and Ottomans launched semi-coordinated military offensives against Iran.

During the Age of Exploration, the Ottomans assisted in anti-Catholic activity among the Sultanates of Southeast Asia. Relations with the Aceh Sultanate started in the 1530s but the affair later developed into an alliance by the 1570s. Thanks to the trade of arms for pepper, the Ottomans gained a foothold in Southeast Asia.[45] By the 1580s, Spanish observers like Melchor Davalos were becoming increasingly alarmed at the number of Ottoman forces operating in the Ternate Sultanate and Brunei Sultanate; the Ottomans helped the Bruneians to expel Spanish invaders once and for all after the Castilian War. Similarly, the Ottomans allied with the Sultanate of Demak to help mitigate Persian and Portuguese influence in Java.[46] Relations with Java continued into the 17th century, even after the Sultanate of Demak was succeeded by the Sultanate of Mataram.[46] Maritime links between the Ottoman Empire and the Toungoo Empire of Burma were established as late as 1545, and persisted well into the 1580s.[45]

Africa

The Ottomans spread the use of firearms into Morocco and Bornu, but Bornu and Morocco later allied against the Ottomans. The Ajuran and Adal Sultanates both allied with the Ottomans against the Portuguese and Ethiopians, as well as the Swahilis, while the Funj Sultanate saw the Ottomans as a threat.

Russo-Turkish War (1676–1681)

The small-scale inconclusive war with Russia in 1676–1681 was a defensive move by Russia after the Ottomans expanded into Podolia during the Polish–Turkish War of 1672–1676. The Porte wanted to take over all of the Right-bank Ukraine with the support of its vassal, Hetman Petro Doroshenko. A combination of Russian and Ukrainian forces defeated Doroshenko and his Turkish-Tatar army in 1676. The invaders were badly defeated by the Russians in 1677 at Chyhyryn and lost again in their attack on Chyhyryn in 1678. In 1679–1680, the Russians repelled the attacks of the Crimean Tatars and signed the Bakhchisaray Peace Treaty on 3 January 1681, which would establish the Russo-Turkish border by the Dnieper.[47]

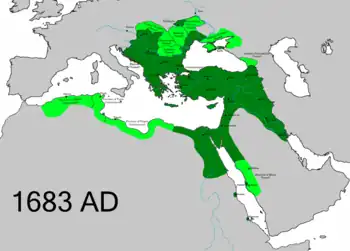

Great Turkish War: 1683–1699

The Great Turkish War or the "War of the Holy League" was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and ad hoc European coalition the Holy League (Latin: Sacra Ligua). The Turks lost.[48] The coalition was organized by Pope Innocent XI and included the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire under Habsburg Emperor Leopold I, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of John III Sobieski, and the Venetian Republic; Russia joined the League in 1686. Intensive fighting began in 1683 when Ottoman commander Kara Mustafa brought an army of 200,000 soldiers to besiege, Vienna.[49] The issue was control of Central and Eastern Europe. By September, the invaders were defeated in full retreat down the Danube. It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The war was a defeat for the Ottoman Empire, which for the first time lost large amounts of territory. It lost lands in Hungary and Poland, as well as part of the western Balkans. The war marked the first time Russia was involved in a western European alliance.[50][51]

Wars with Russia, 1768–1774

Following a border incident at Balta, Sultan Mustafa III declared war on Russia on 25 September 1768. The Turks formed an alliance with the Polish opposition forces of the Bar Confederation, while Russia was supported by Great Britain, which offered naval advisers to the Russian navy.[52][53]

The Polish opposition was defeated by Alexander Suvorov. He was then transferred to the Ottoman theatre of operations, where in 1773 and 1774 he won several minor and major battles following the previous grand successes of the Russian Field-Marshal Pyotr Rumyantsev at Larga and Kagula.[54]

Naval operations of the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Mediterranean yielded victories under the command of Aleksey Grigoryevich Orlov. In 1771, Egypt and Syria rebelled against the Ottoman rule, while the Russian fleet totally destroyed the Ottoman Navy at the battle of Chesma.[55]

On 21 July 1774, the defeated Ottomans signed the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, which formally granted independence to the Crimean Khanate; in reality it became dependent on Russia. Russia received 4.5 million rubles and two key seaports allowing the direct access to the Black Sea.[56]

The supply of Ottoman forces operating in Moldavia and Wallachia was a major challenge that required well organized logistics. An army of 60,000 soldiers and 40,000 horses required a half-million kilograms of food per day. The Ottoman forces fared better than the Russians, but the expenses crippled both national treasuries. Supplies on both sides came using fixed prices, taxes, and confiscation.[57]

19th century

As the 19th century progressed, the Ottoman Empire grew weaker and Britain increasingly became its protector, even fighting the Crimean War in the 1850s to help it out against Russia.[58][59] Three British leaders played major roles. Lord Palmerston in the 1830–65 period considered the Ottoman Empire an essential component in the balance of power and was the most favourable toward Constantinople. William Gladstone in the 1870s sought to build a Concert of Europe that would support the survival of the empire. In the 1880s and 1890s Lord Salisbury contemplated an orderly dismemberment of it, in such a way as to reduce rivalry between the greater powers.[60]

Selim III

Selim III (1789–1807) in 1789 found that the Empire had been considerably reduced due to conflicts outside the realm. From the north Russia had taken the Black Sea through the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774. Selim realized the importance of diplomatic relations with other nations, and pushed for permanent embassies in the courts of all the great nations of Europe, a hard task because of religious prejudice towards Muslims. Even with the religious obstacles, resident embassies were established in London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna.[61] Selim, a cultured poet and musician, carried on an extended correspondence with Louis XVI of France. Although distressed by the establishment of the republic in France, Ottoman government was soothed by French representatives in Constantinople who maintained the goodwill of various influential personages.[62][63] In July 1798, however, French forces under Napoleon landed in Egypt, and Selim declared war on France. In alliance with Russia and Britain, the Turks were in periodic conflict with the French on both land and sea until March 1801. Peace came in June 1802, The following year brought trouble in the Balkans. For decades a sultan's word had had no power in outlying provinces, prompting Selim's reforms of the military in order to reimpose central control. This desire was not fulfilled. One rebellious leader was Austrian-backed Osman Pazvantoğlu, whose invasion of Wallachia in 1801 inspired Russian intervention, resulting in greater autonomy for the Dunubian provinces. Serbian conditions also deteriorated. They took a fateful turn with the return of the hated Janissaries, ousted 8 years before. These forces murdered Selim's enlightened governor, ending the best rule this province had had in the last 100 years.[64] Neither arms nor diplomacy could restore Ottoman authority.

Loss of Egypt: 1798–1805

The brief French invasion of Egypt led by Napoleon Bonaparte began in 1798. Napoleon won early victories and made an initially successful expedition into Syria. The British Royal Navy sank the French fleet at Battle of the Nile. Napoleon managed to escape with a small staff in 1799, leaving the army behind. When peace with Britain came (briefly) in 1803 Napoleon brought home his Armée d'Orient.[65] The expulsion of the French in 1801 by Ottoman, Mamluk, and British forces was followed by four years of anarchy in which Ottomans, Mamluks, and Albanians — who were nominally in the service of the Ottomans – wrestled for power. Out of this chaos, the commander of the Albanian regiment, Muhammad Ali (Kavalali Mehmed Ali Pasha) emerged as a dominant figure and in 1805 was acknowledged by the Sultan as his "viceroy" in Egypt; the title implied subordination to the Sultan but this was in fact a polite fiction: Ottoman power in Egypt was finished and Muhammad Ali, an ambitious and able leader, established a dynasty in Egypt that lasted until 1952.[66]

Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812)

French influence with the Sublime Porte led the Sultan into defying both St. Petersburg and London, and instead joined Napoleon's Continental System. War was declared on Russia on 27 December and on Britain in March 1807. The Ottomans did poorly. Constantinople negotiated for peace in the Treaty of Bucharest (1812). The Porte above all wanted to stay out of the impending conflict between Napoleon and Russia. The Russians wanted no side war and thus they made peace in order to be free for the potential war with France. The Treaty of Bucharest ceded to Russia the eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia, as well as Bessarabia. Russia obtained trading rights on the Danube. The Porte ended hostilities and granted autonomy to Serbia. In Transcaucasia, the Ottomans renounced their claims to most of western Georgia. Russia returned control of Akhalkalaki, Poti, and Anapa.[67] The Ottomans had extricated themselves from a potentially disastrous war with a slight loss of territory. This treaty became the basis for future Russo-Ottoman relations.[68]

Greek War of Independence 1821–1830

The Greek War of Independence was a successful uprising waged by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1830. The Greeks were factionalized and fought their own civil war. The Greeks won widespread support from elite opinion in Europe, and were aided militarily and diplomatically by Great Britain, France and Russia. The Ottomans were aided militarily by Egypt.[69][70]

Greece came under Ottoman rule in the late 15th century. During the following centuries, there were sporadic but unsuccessful Greek uprisings against Ottoman rule. In 1814, a secret organization called Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends) was founded with the aim of liberating Greece, encouraged by the revolutionary fervor gripping Europe in that period. The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolts in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities, and Constantinople itself, which had a large Greek element. The first revolt began on 6 March/21 February 1821 in the Danubian Principalities, but it was soon put down by the Ottomans. The events in the north urged the Greeks in the Peloponnese (Morea) into action and on 17 March 1821, the Maniots were first to declare war. In September 1821, the Greeks under the leadership of Theodoros Kolokotronis captured Tripolitsa. Revolts in Crete, Macedonia, and Central Greece broke out, but were eventually suppressed. Meanwhile, makeshift Greek fleets achieved success against the Ottoman Navy in the Aegean Sea and prevented Ottoman reinforcements from arriving by sea.

Tensions soon developed among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. The Ottoman Sultan called in Muhammad Ali of Egypt, who sent his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gains. Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese in February 1825 and brought most of the peninsula under Egyptian control by the end of that year. Despite a failed invasion of Mani, Athens also fell and the revolution looked all but lost.

At that point, the three Great Powers—Russia, Britain and France—decided to intervene, sending their naval squadrons to Greece in 1827. Following news that the combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleet was going to attack the island of Hydra, the allied fleets intercepted the Ottoman navy and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Navarino. In 1828 the Egyptian army withdrew under pressure of a French expeditionary force. The Ottoman garrisons in the Peloponnese surrendered, and the Greek revolutionaries proceeded to retake central Greece. Russia invaded the Ottoman Empire and forced it to accept Greek autonomy in the Treaty of Adrianople (1829). After nine years of war, Greece was finally recognized as an independent state under the London Protocol of February 1830. Further negotiations in 1832 led to the London Conference and the Treaty of Constantinople; these defined the final borders of the new state and established Prince Otto of Bavaria as the first king of Greece.

Serbian Revolution and Autonomous Principality (1804–1878)

Serbia gained considerable internal autonomy from the Ottoman Empire in two uprisings in 1804 (led by Đorđe Petrović – Karađorđe) and 1815 (led by Miloš Obrenović). Ottoman troops continued to garrison the capital, Belgrade, until 1867. The Serbs launched not only a national revolution but a social one as well. Complete independence arrived in 1878. Serbian activists promoted ethnic nationalism in the Balkans, targeting both the remnants of the Ottoman Empire and the equally fragile Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Serbia followed Montenegro against the Ottomans, and one full independence from the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Serbia played a central role in the Balkan wars of the early 20th century, which practically eliminated the Ottoman presence in Europe[71]

Russo-Turkish War (1828–29)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 was sparked by the Greek War of Independence of 1821–1829. War broke out after the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II closed the Dardanelles to Russian ships and revoked the 1826 Akkerman Convention in retaliation for Russian participation in October 1827 in the Battle of Navarino. The results included Russian victory, Treaty of Adrianople, Russian occupation of Danubian Principalities, Greek victory and independence from the Ottoman Empire

Persian Gulf

Britain planned bases in the Persian Gulf region to protect India. Yemen was the first choice, since it was a convenient port. By 1800 the Porte permitted the creation of British trading stations in Mocha, Yemen. British intrigues with local leaders troubled the Porte which in 1818 asked Muhammad Ali to pacify the region. The British government worked with Ali to take over the strategically significant port of Aden, despite opposition from Constantinople.[72]

The Ottomans were concerned about the British expansion from India into the Red Sea and Arabia. They returned to the Tihamah in 1849 after an absence of two centuries.[73]

Financial crisis

Economic stagnation prevailed in Ottoman lands areas in the 1840s and 1850s at a time when rapid industrialization characterized Britain and Western Europe—areas that also expanded their commerce in the Levant. The Porte had serious economic problems—stagnant tax revenue, inflation, growing expenses. Despite the sultan's fear of British penetration, it borrowed heavily from banks in Paris and London and did not set up its own banks.[74]

Crimean War 1854–56

The Crimean War (1854–56) was fought between Russia on the one hand and an alliance of Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire on the other. Russia was defeated but the casualties were very heavy on all sides, and historians look at the entire episode as a series of blunders.[75][76]

The war began with Russian demands to protect Christian sites in the Holy Land. The churches quickly settled that problem, but it escalated out of hand as Russia put continuous pressure on the Ottomans. Diplomatic efforts failed. The Sultan declared war against Russia in October 1851. Following an Ottoman naval disaster in November, Britain and France declared war against Russia.[77] It proved quite difficult to reach Russian territory, and the Royal Navy could not defeat the Russian defences in the Baltic. Most of the battles took place in the Crimean peninsula, which the Allies finally seized. London, shocked to discover that France was secretly negotiating with Russia to form a postwar alliance to dominate Europe, dropped its plans to attack St. Petersburg and instead signed a one-sided armistice with Russia that achieved almost none of its war aims.

The Treaty of Paris signed 30 March 1856, ended the war. Russia gave up a little land and relinquished its claim to a protectorate over the Christians in the Ottoman domains. The Black Sea was demilitarized, and an international commission was set up to guarantee freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube River. Moldavia and Wallachia remained under nominal Ottoman rule, but would be granted independent constitutions and national assemblies. However, by 1870, the Russians had regained most of their concessions.[78]

The war helped modernize warfare by introducing major new technologies such as railways, the telegraph, and modern nursing methods. The Ottoman Empire and Russia, with their weak industrial bases, could not keep up with the major powers, so they could no longer promote stability. This opened the way for Napoleon III in France and Otto von Bismarck in Prussia to launch a series of wars in the 1860s that reshaped Europe.[79]

Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 saw the Ottomans lose to a coalition led by the Russian Empire and composed of Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro. Russia and its allies declared war in order to gain access to the Mediterranean through the Turkish Straits. The main battles were fought on land in Anatolia/Caucasus and Rumelia. After losing the siege at Plevna, the Ottomans gave up and signed the punitive Treaty of San Stefano. That treaty built up a powerful Bulgaria. The European powers rejected that solution and met at the Congress of Berlin. Even though the Porte was not invited the powers returned half the Ottoman losses at the Treaty of Berlin in July 1878. The war originated in emerging Balkan nationalism and Orthodox Christian religion. Additional factors included Russian goals of recovering territorial losses endured during the Crimean War of 1853–56, re-establishing itself in the Black Sea and supporting the political movement attempting to free Balkan nations from the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Russia succeeded in claiming provinces in the Caucasus (Kars and Batum). Russia also annexed the Budjak region. The principalities of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro, each of which had de facto sovereignty for some time, formally proclaimed independence from the Porte. After almost five centuries of Ottoman domination (1396–1878), a Bulgarian state re-emerged: the Principality of Bulgaria, covering the land between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains (except Northern Dobrudja which was given to Romania), as well as the region of Sofia, which became Bulgaria's capital. The Congress of Berlin also allowed Austria-Hungary to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina and Great Britain to take over Cyprus.[80]

A surprising consequence came in Hungary (part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Despite memories of the terrible defeat at Mohács in 1526, elite Hungarian attitudes were become strongly anti-Russian This led to active support for the Turks in the media, but only in a peaceful way, since the foreign policy of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy remained neutral.[81]

British takeover of Egypt, 1882

The most decisive event emerged from the Anglo-Egyptian War, which resulted in the occupation of Egypt. although the Ottoman Empire was the nominal owner, in practice Britain made all the decisions.[82] In 1914, Britain went to war with the Ottomans and ended their nominal role. Historian A. J. P. Taylor says that the seizure, which lasted seven decades, "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia and the Russo-Japanese war."[83] Taylor emphasizes long-term impact:

- The British occupation of Egypt altered the balance of power. It not only gave the British security for their route to India; it made them masters of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East; it made it unnecessary for them to stand in the front line against Russia at the Straits....And thus prepared the way for the Franco-Russian Alliance ten years later.[84]

20th century

In 1897 the population was 19 million, of whom 14 million (74%) were Muslim. An additional 20 million lived in provinces which remained under the sultan's nominal suzerainty but were entirely outside his actual power. One by one the Porte lost nominal authority. They included Egypt, Tunisia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Lebanon.[85]

Entry in to World War I

Germany for years had worked to develop closer ties to the Ottoman Empire. In 1914, the old Ottoman enemy Russia was at war with Germany and Austria-Hungary, and Constantinople distrusted London for its role in Egypt.[86] Conquest of Constantinople was a main Russian war goal. The Porte was neutral at first but leaned toward Germany. Its old protector Britain was no longer a close ally. The Ottoman entry into World War I began when two recently purchased ships of its navy, still manned by their German crews and commanded by their German admiral, carried out the Black Sea Raid, a surprise attack against Russian ports, on 29 October 1914. Russia replied by declaring war on 1 November 1914 and Russia's allies, Britain and France, then declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 5 November 1914.[87]

There were a number of factors that conspired to influence the Ottoman government, and encourage them into entering the war. According to Kemal Karpat:

- Ottoman entry into the war was not the consequence of careful preparation and long debate in the parliament (which was recessed) and press. It was the result of a hasty decision by a handful of elitist leaders who disregarded democratic procedures, lacked long-range political vision, and fell easy victim to German machinations and their own utopian expectations of recovering the lost territories in the Balkans. The Ottoman entry into war prolonged it for two years and allowed the Bolshevik revolution to incubate and then explode in 1917, which in turn profoundly impacted the course of world history in the 20th century.[88]

This decision ultimately led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Ottomans, the Armenian genocide, the dissolution of the empire, and the abolition of the Islamic Caliphate.[89]

See also

- International relations, 1648–1814

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- British foreign policy in the Middle East

- Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe British ambassador

- Persian-Ottoman relations

- Russia–Turkey relations

- Ottoman Empire–United States relations

- List of diplomatic missions of the Ottoman Empire

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ottoman Empire)

- Foreign relations of Turkey

- Military of the Ottoman Empire

- State organisation of the Ottoman Empire

- Decline and modernization of the Ottoman Empire

References

- ↑ See Foundations of the Ottoman Foreign Ministry International Journal of Middle East Studies, 1974

- ↑ Eliana Balla and Noel D. Johnson, "Fiscal crisis and institutional change in the Ottoman Empire and France." Journal of Economic History (2009) 69#3 pp: 809–845 online.

- ↑ Sevket Pamuk, "The evolution of financial institutions in the Ottoman Empire, 1600–1914." Financial History Review 11.1 (2004): 7–32. online.

- 1 2 Yurdusev et al., 2.

- ↑ Watson, 218.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., Ottoman Diplomacy p. 27.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 30.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 39.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 39–40.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 41.

- 1 2 Watson, 217.

- ↑ Robert Olson, "The Ottoman-French Treaty of 1740" Turkish Studies Association Bulletin (1991) 15#2 pp. 347–355 online

- ↑ Stanford J. Shaw, "The Nizam-1 Cedid Army under Sultan Selim III 1789–1807." Oriens 18.1 (1966): 168–184 online.

- ↑ David Nicolle, Armies of the Ottoman Empire 1775–1820 (Osprey, 1998).

- ↑ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History (1977) pp 388–389.

- 1 2 3 Watson, 177.

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 21.

- ↑ Dupuy and Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History (1977) pp 437–438.

- ↑ G. R. Potter, "The Fall of Constantinople? History Today (Jan 1953) 3#1 pp 41–49.

- ↑ Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time (Princeton UP 1992)

- ↑ Yurdusev et al., 22.

- ↑ Dupuy and Dupuy, Encyclopedia of Military History (1977) p 439.

- ↑ Inalcik, 36.

- 1 2 Dupuy and Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History (1977) pp 495–501.

- 1 2 Farooqi, Naimur Rahman (2008). Mughal-Ottoman relations: a study of political & diplomatic relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556-1748. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2007), Emperors Of The Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 27–29, ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7

- ↑ Chandra 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ Güneş Işıksel, "Suleiman the Magnificent (1494–1566)." in The Encyclopedia of Diplomacy (2018): 1–2 online.

- ↑ Metin Kunt and Christine Woodhead, Suleyman the Magnificent & His Age: The Ottoman Empire in the Early Modern World (1995).

- ↑ Rhoads Murphey, "Süleyman I and the Conquest of Hungary: Ottoman Manifest Destiny or a Delayed Reaction to Charles V's Universalist Vision." Journal of Early Modern History 5.3 (2001): 197–221.

- ↑ Viorel Panaite, "Power Relationships in the Ottoman Empire: The Sultans and the Tribute-Paying Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century." International Journal of Turkish Studies 7.1–2 (2001): 26–54.

- ↑ Subhi Labib, "The era of Suleyman the magnificent: crisis of orientation." International journal of Middle East studies 10.4 (1979): 435–451. Online

- ↑ John D. Norton, "Sultan Süleyman's Marred Magnificence." Historian (1986), Issue 11, pp 3–8.

- ↑ Watson, 222.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (February 2016). "Between Two Universal Empires: Ottoman-China Connections in the Sixteenth Century". Yale InterAsia Connections Conference: Alternative Asias: Currents, Crossings, Connection, 2016.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ↑ Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 0521822742. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ↑ "The Tūqmāq (Golden Horde), the Qazaq Khanate, the Shībānid Dynasty, Rūm (Ottoman Empire), and Moghūlistan in the XIV-XVI Centuries: from Original Sources" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Tūqmāq (Golden Horde), the Qazaq Khanate, the Shībānid Dynasty, Rūm (Ottoman Empire), and Moghūlistan in the XIV-XVI Centuries: from Original Sources" (PDF).

- ↑ Casale, Giancarlo (28 January 2010). The Ottoman Age of Exploration. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195377828.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8.

- 1 2 3 Casale, Giancarlo (28 January 2010). The Ottoman Age of Exploration. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195377828.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8.

- 1 2 Meirison, Meirison; Trinova, Zulvia; Eri Firdaus, Yelmi (20 December 2020). "The Ottoman Empire Relations with the Nusantara (Spice Islands)". Tabuah. 24 (2): 140–147. doi:10.37108/tabuah.v24i2.313. ISSN 2614-7793. S2CID 238960772.

- ↑ Lucjan Ryszard Lewitter, "The Russo-Polish Treaty of 1686 and Its Antecedents." Polish Review (1964): 5–29 online.

- ↑ Lewitter, "The Russo-Polish Treaty of 1686 and Its Antecedents." Polish Review (1964): 5–29 online.

- ↑ Simon Millar, Vienna 1683: Christian Europe Repels the Ottomans (Osprey, 2008)

- ↑ John Wolf, The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715 (1951), pp 15–53.

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton, Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 1991) excerpt

- ↑ Brian Davies (16 June 2011). Empire and Military Revolution in Eastern Europe: Russia's Turkish Wars in the Eighteenth Century. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-6238-0.

- ↑ Brian L. Davies, The Russo-Turkish War, 1768-1774: Catherine II and the Ottoman Empire (Bloomsbury, 2016).

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 862. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ↑ "Battle of Çeşme". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ "Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ Virginia H. Aksan, "Feeding the Ottoman troops on the Danube, 1768–1774." War & Society 13.1 (1995): 1–14.

- ↑ Margaret M. Jefferson, "Lord Salisbury and the Eastern Question, 1890-1898." Slavonic and East European Review (1960): 44-60. online

- ↑ Frank E. Bailey, "The Economics of British Foreign Policy, 1825–50." Journal of Modern History 12.4 (1940): 449–484 online.

- ↑ David Steele, "Three British Prime Ministers and the Survival of the Ottoman Empire, 1855–1902." Middle Eastern Studies 50.1 (2014): 43–60.

- ↑ Carter V. Findley, "The foundation of the Ottoman Foreign Ministry: the beginnings of bureaucratic reform under Selîm III and Mahmûd II." International Journal of Middle East Studies 3.4 (1972): 388–416 online.

- ↑ Stanford, Shaw (1965). "The Origins of Ottoman Military Reform: The Nizam-I Cedid Army of Sultan Selim III". The Journal of Modern History. 37 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1086/600691. JSTOR 1875404. S2CID 145786017.

- ↑ Thomas Naff, "Reform and the Conduct of Ottoman Diplomacy in the Reign of Selim III, 1789-1807." Journal of the American Oriental Society 83.3 (1963): 295-315 online.

- ↑ Selim, III Biography. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Paul Strathern, Napoleon in Egypt: The Greatest Glory (2007) online

- ↑ M. Abir, "Modernisation, Reaction and Muhammad Ali's 'Empire'" Middle Eastern Studies 13#3 (1977), pp. 295–313 online

- ↑ John F. Baddeley, Russian Conquest of the Caucasus (1908), Chapter V

- ↑ F. Ismail, "The making of the treaty of Bucharest, 1811–1812," Middle Eastern Studies (1979) 15#2 pp 163–192 online.

- ↑ W. Alison Phillips, The war of Greek independence, 1821 to 1833 (1897) online

- ↑ J. A. R. Marriott, The Eastern Question An Historical Study in European Diplomacy (1940) pp 193–225. online

- ↑ Harry N. Howard, "The Balkan Wars in perspective: their significance for Turkey." Balkan Studies 3.2 (1962): 267–276.

- ↑ Caesar E. Farah, "Reaffirming Ottoman Sovereignty in Yemen, 1825–1840" International Journal of Turkish Studies (1984) 3#1 pp 101–116.

- ↑ Caesar E. Farah (2002). The Sultan's Yemen: 19th Century Challenges to Ottoman Rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 120. ISBN 9781860647673.

- ↑ Frederick S. Rodkey, "Ottoman Concern about Western Economic Penetration in the Levant, 1849–1856." Journal of Modern History 30.4 (1958): 348–353 online.

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) pp 62–82

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, "The war that would not boil," History Today (1951) 1#2 pp 23–31.

- ↑ Kingsley Martin, The triumph of Lord Palmerston: a study of public opinion in England before the Crimean War (Hutchinson, 1963). online

- ↑ Harold Temperley, "The Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution," Journal of Modern History (1932) 4#3 pp. 387–414 in JSTOR

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee, Aspects of European History 1789–1980 (2001) pp 67–74

- ↑ Gültekin Yildiz, "Russo-Ottoman War, 1877–1878." in Richard C. Hall, ed., War in the Balkans (2014): 256–258 online.

- ↑ Iván Bertényi, "Enthusiasm for a Hereditary Enemy: Some Aspects of The Roots of Hungarian Turkophile Sentiments." Hungarian Studies 27.2 (2013): 209–218 online.

- ↑ Selim Deringil, "The Ottoman Response to the Egyptian Crisis of 1881–82" Middle Eastern Studies (1988) 24#1 pp. 3–24 online

- ↑ He adds, "All the rest were maneuvers which left the combatants at the close of the day exactly where they had started. A.J.P. Taylor, "International Relations" in F.H. Hinsley, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History: XI: Material Progress and World-Wide Problems, 1870–98 (1962): 554.

- ↑ Taylor, "International Relations" p 554

- ↑ Stanford J. Shaw and Ezel Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (1977) 2:236.

- ↑ Kemal H. Karpat, "The entry of the Ottoman empire into world war I." Belleten 68.253 (2004): 1–40. online

- ↑ Ali Balci, et al. "War Decision and Neoclassical Realism: The Entry of the Ottoman Empire into the First World War." War in History (2018), doi:10.1177/0968344518789707 online

- ↑ Kemal Karpat, 2004.

- ↑ Yiğit Akın, When the War Came Home: The Ottomans' Great War and the Devastation of an Empire. (Stanford Up, 2018) excerpt.

Further reading

- Aksan, Virginia. Ottoman Wars, 1700–1870: An Empire Besieged (Routledge, 2014) excerpt

- Anderson, M.S. The Eastern Question 1774–1923 (1966)

- Bailey, Frank E. "The Economics of British Foreign Policy, 1825–50." Journal of Modern History 12.4 (1940): 449–484, focus on Ottomans. online

- Bailey, Frank Edgar. British policy and the Turkish reform movement: a study in Anglo-Turkish relations, 1826–1853 (Harvard UP, 1942).

- Bloxham, Donald. The great game of genocide: imperialism, nationalism, and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians (Oxford UP, 2005).

- Dávid, Géza–Fodor, Pál (eds.): Hungarian–Ottoman Military and Diplomatic Relations in the Age of Süleyman the Magnificent (ELTE, Budapest, 1994) https://tti.abtk.hu/kiadvanyok/kiadvanytar/david-geza-fodor-pal-eds-hungarian-ottoman-military-and-diplomatic-relations-in-the-age-of-suleyman-the-magnificent/download

- Davison, Roderic H. Nineteenth century Ottoman diplomacy and reforms (Isis Press, 1999).

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy. The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present (1986 and other editions), passim and 1463–1464.

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923 (Basic, 2005) excerpt.

- Geyikdağı, Necla. "The Evolution of British Commercial Diplomacy in the Ottoman Empire." İktisat ve Sosyal Bilimlerde Güncel Araştırmalar 1.1: 9–46. online in English

- Geyikdağı, N. Foreign Investment in the Ottoman Empire: International Trade and Relations 1854–1914 (I.B. Tauris, 2011).

- Hale, William. Turkish foreign policy since 1774 (Routledge, 2012) pp 8–33 on Ottomans. excerpt.

- Hall, Richard C. ed. War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia (2014)

- Hitzel, Frédéric (2010). "Les ambassades occidentales à Constantinople et la diffusion d'une certaine image de l'Orient". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 154 (1): 277–292.

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 352–77.

- Hurewitz, Jacob C. "Ottoman diplomacy and the European state system." Middle East Journal (1961) 15#2: 141–152 online.

- Inalcik, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. (Praeger, 1971). ISBN 1-84212-442-0.

- Karpat, Kemal H. "The entry of the ottoman empire into world war I." Belleten 68.253 (2004): 1–40. online

- Kent, Marian. "Agent of empire? The National Bank of Turkey and British foreign policy." Historical Journal 18.2 (1975): 367–389 online.

- Kent, Marian, ed. The Great Powers and the end of the Ottoman Empire (Routledge, 2005).

- Langer, William L. The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (1965).

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon. The Eastern Question 1774–1923 (2nd ed Routledge, 2014).

- Marriott, J. A. R. The Eastern question: an historical study in European diplomacy (1940) online.

- Mátyás király levelei [Diplomatic letters of Matthias Corvinus-some of them to Emperos Mehmed II and Emperor Bayezid II]: Külügyi osztály / közreadó Fraknói Vilmos tartalma: Első kötet, 1458-1479; Második kötet, 1480-1490. https://mek.oszk.hu/07100/07105/# [6 letter for the Ottoman Sultans, 1 for pasha of Sendro, 1 for prince Cem Volume I: letter 259. (381 p),260(pasha of Sendro), 263, letter, Volume II: letter:140.(242.p)to Cem, 169(1484? to Bayezid II), 174 (29. p), 247.(1480? to Mehmed II. (p 388),

- Merriman, Roger Bigelow. Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566 (Harvard UP, 1944) online

- Miller, William. The Ottoman Empire and its successors, 1801–1922 (2nd ed 1927) online, strong on foreign policy

- Palmer, Alan. The Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire (1994).

- Pálosfalvi, Tamás. From Nicopolis to Mohács: A History of Ottoman-Hungarian Warfare, 1389–1526 (Brill, 2018)

- Pamuk, Şevket. The Ottoman Empire and European Capitalism, 1820–1913: Trade, Investment and Production (Cambridge UP, 1987).

- Quataert, Donald. The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (Cambridge UP, 2000).

- I Rakoczi György es a Porta Levelek es diplomaciai iratok[George> Rakoczi I and the Porta[=Ottoman government. Letters and diplomatic documents] https://vmek.oszk.hu/mobil/konyvoldal.phtml?id=20116#_home

- Rodogno, Davide. Against Massacre: Humanitarian Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, 1815–1914 (Princeton UP, 2012).

- Shaw, Stanford J. Between Old and New: The Ottoman Empire Under Sultan Selim III, 1789–1807 (Harvard UP, 1971)

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (2 vol. Cambridge UP, 1976)..

- Talbot, Michael. British-Ottoman Relations, 1661–1807: Commerce and Diplomatic Practice in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul' (Boydell Press, 2007) online

- Tardy, Lajos: Beyond the Ottoman Empire : 14th-16th century Hungarian [and Habsburg Anti-Ottoman] diplomacy in the East 1978 Szeged JATE transl. by János Boris[from Emperor Sigismund to Emperor Rudolph].

- Watson, Adam. The evolution of international society: a comparative historical analysis. (Routledge, 1992). .

- Yaycioglu, Ali. "Révolutions De Constantinople: France and the Ottoman World in the Age of Revolutions". in French Mediterraneans: Transnational and Imperial Histories, ed by Patricia M. E. Lorcin and Todd Shepard (U of Nebraska Press, 2016), pp. 21–51. online

- Yurdusev, A. Nuri et al. Ottoman Diplomacy: Conventional or Unconventional?. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). ISBN 0-333-71364-8.

- Chandra, Satish (2009). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, Part II. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124110669.

Primary sources

- Anderson, M.S. ed. The great powers and the Near East, 1774–1923 (Edward Arnold, 1970).

- Bourne, Kenneth, ed. The Foreign Policy of Victorian England 1830–1902 (1970); 147 primary documents, plus 194-page introduction. online free to borrow

- Hurewitz, J. C. ed. The Middle East and North Africa in world politics: A documentary record vol 1: European expansion: 1535–1914 (1975); vol 2: A Documentary Record 1914–1956 (1956)vol 2 online