.jpg.webp)

Painting in the Americas before European colonization is the Precolumbian painting traditions of the Americas. Painting was a relatively widespread, popular and diverse means of communication and expression for both religious and utilitarian purpose throughout the regions of the Western Hemisphere. During the period before and after European exploration and settlement of the Americas; including North America, Central America, South America and the islands of the Caribbean, the Bahamas, the West Indies, the Antilles, the Lesser Antilles and other island groups, indigenous native cultures produced a wide variety of visual arts, including painting on textiles, hides, rock and cave surfaces, bodies especially faces, ceramics, architectural features including interior murals, wood panels, and other available surfaces. Many of the perishable surfaces, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

The oldest known paintings in the South America are the cave paintings of Caverna da Pedra Pintada, in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest that date back 11,200 years.[1] The earliest known painting in North America is the Cooper Bison Skull found near Fort Supply, Oklahoma, dated to 10,200 BCE.[2]

Painting in the Americas before colonization

Each continent of the Americas hosted societies that were unique and individually developed cultures; that produced totems, works of religious symbolism, and decorative and expressive painted works. African influence was especially strong in the art of the Caribbean and South America. The arts of the indigenous people of the Americas had an enormous impact and influence on European art and vice versa during and after the Age of Exploration. Spain, Portugal, France, The Netherlands and England were all powerful and influential colonial powers in the Americas during and after the 15th century. By the 19th century cultural influence began to flow both ways across the Atlantic.

Mesoamerica

The murals of Teotihuacan that adorn the archaeological site (and others, like the Wagner Murals, found in private collections) and from hieroglyphic inscriptions made by the Maya describing their encounters with Teotihuacano conquerors are the source of most of what is understood about that ancient civilization. The painting of the murals, perhaps thousands of them, reached its zenith between 450 and 650 CE. The painters' artistry was unrivalled in Mesoamerica and has been compared with that of Florence, Italy.[3]

The Great Goddess

A series of murals were found in the Tepantitla compound in Teotihuacan. In 1942, archaeologist Alfonso Caso identified the central figures as a Teotihuacan equivalent of Tlaloc, the Mesoamerican god of rain and warfare. During the 1970s researcher Esther Pasztory re-examined the murals and concluded that many paintings of "Tlaloc" instead showed a feminine deity, an analysis based on a number of factors including the gender of accompanying figures, the green bird in the headdress, and the spiders seen above the figure.[4] Pasztory concluded that the figures represented a vegetation and fertility goddess that was a predecessor of the much later Aztec goddess Xochiquetzal.

The Great Goddess has since been identified at locations other than Tepantitla – including Teotihuacan's Tetitla compound, the Palace of the Jaguars, and the Temple of Agriculture – as well as on several vessels.[5]

The Temple of the Murals

Large painted Mayan murals were found in the archaeological site Bonampak, in the Mexican state of Chiapas near the border with Guatemala. What is referred to as The Temple of the Murals is a long narrow building with 3 rooms atop a low-stepped pyramid base. The interior walls preserve the finest examples of classic Maya painting. Huge paintings cover the walls of one of the structure's three rooms. The paintings show the story of a single battle and its victorious outcome.[6]

Great Goddess of Teotihuacan mural from the site at Tetitla, Mexico

Great Goddess of Teotihuacan mural from the site at Tetitla, Mexico.jpg.webp) Mural from the Complex of Tepantitla in Teotihuacan, a reproduction in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City

Mural from the Complex of Tepantitla in Teotihuacan, a reproduction in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City Mural of the Jaguars compound in Teotihuacan.

Mural of the Jaguars compound in Teotihuacan. Reconstruction of the Tomb 105 from Monte Alban.

Reconstruction of the Tomb 105 from Monte Alban. Portic A from Cacaxtla, represent the Man-jaguar

Portic A from Cacaxtla, represent the Man-jaguar Detail from the Red Temple, c.600–700, Cacaxtla, Mexico

Detail from the Red Temple, c.600–700, Cacaxtla, Mexico A Mayan mural from Bonampak, Mexico, 580–800 AD.

A Mayan mural from Bonampak, Mexico, 580–800 AD. A Mayan mural from Bonampak, 580–800 AD

A Mayan mural from Bonampak, 580–800 AD A Mayan mural from San Bartolo, Pre-Classical period (1–250 AD)

A Mayan mural from San Bartolo, Pre-Classical period (1–250 AD) Painting on the Lord of the jaguar pelt throne vase, a scene of the Maya court, 700–800 AD.

Painting on the Lord of the jaguar pelt throne vase, a scene of the Maya court, 700–800 AD. Painting on a Maya vase from the Late Classical Period (600–900)

Painting on a Maya vase from the Late Classical Period (600–900).jpg.webp) Painted pottery figurine of a King from the burial site at Jaina Island, Mayan art, 400–800 AD

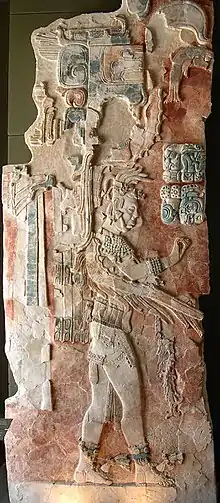

Painted pottery figurine of a King from the burial site at Jaina Island, Mayan art, 400–800 AD Painted relief of the Maya site Palenque, featuring the son of K'inich Ahkal Mo' Naab' III (678–730s?, r. 722–729).

Painted relief of the Maya site Palenque, featuring the son of K'inich Ahkal Mo' Naab' III (678–730s?, r. 722–729). Painting from a Dresden Codex.

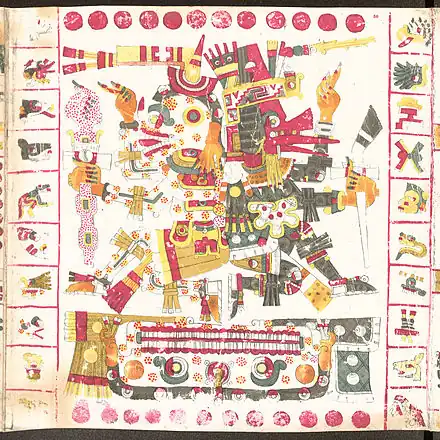

Painting from a Dresden Codex. A Mixtec painting from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall.

A Mixtec painting from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall.

.jpg.webp)

A painting from Matrícula de Tributos showing the Ichcahuipilli, Mexico.

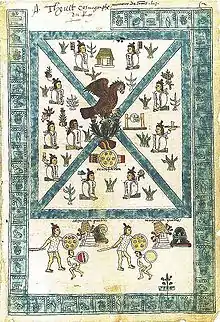

A painting from Matrícula de Tributos showing the Ichcahuipilli, Mexico. A painting from Codex Mendoza showing the Aztec legend of the foundation of Tenochtitlán, c.1553

A painting from Codex Mendoza showing the Aztec legend of the foundation of Tenochtitlán, c.1553

South America

Nazca culture

The Nazca culture of Peru produced painted pottery and painted ceramics depicting religious and symbolic characters as well as imagery of personages within the culture.[7] They produced in addition to ceramics, highly complex textiles and Geoglyphs. The period from 1-700 A.D is generally considered when this group thrived. Modern knowledge about the culture of the Nazca is built upon the study of Cahuachi the ceremonial center from (1-500 AD).

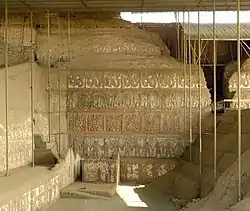

Mural in Huaca Cao Viejo, in Peru.

Mural in Huaca Cao Viejo, in Peru.

Peruvian Calabas

Peruvian Calabas

North America

United States

- Main: Native American art

In the area now part of the United States, many different and diverse Native American tribes of people created painting and ornamental painted objects of a large variety. The oldest known example is the Cooper Bison skull, which was painted with a red zigzag circa 10,200 BCE in present-day Oklahoma.[8] Body painting, rock art, hide painting flourished in ancient North America, as well as painting on ceramics, textiles, and other surfaces.

Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) of the American Southwest have a longstanding tradition of painting interior murals and ceramics, as did the Mogollon culture, ancestors of Zuni and Hopi tribes, who lived in an area near the Gila Wilderness. The Fremont culture of Utah are known for their abundant rock paintings throughout Utah, particularly those at Range Creek Canyon.[9] The Patayan typically painted ceramics with a red slip. The Hohokam, ancestors of the Akimel O'odham and Tohono O'odham, are known for their red-on-buff painted ceramics.[10] Casa Grande Ruins National Monument is the best known monument of Hohokam culture.

Native Americans in California created many pieces and environments of rock art. The most elaborate and artistic painted pictographs being the Rock art of the Chumash people, and petroglyphs those of the Coso people in the Coso Rock Art District.[11]

Ancient Northwest Coast art features formline painting on woven items and wood; however, few of these items survived the centuries the temperate rainforest climate.

The Great Gallery, Pictographs, Canyonlands National Park, Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, 15 feet by 200 feet, ca. 1500 BCE

The Great Gallery, Pictographs, Canyonlands National Park, Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, 15 feet by 200 feet, ca. 1500 BCE

Painted ceramic jug showing the underwater panther from the Mississippian culture, found at Rose Mound in Cross County, Arkansas, ca. 1400-1600 CE.

Painted ceramic jug showing the underwater panther from the Mississippian culture, found at Rose Mound in Cross County, Arkansas, ca. 1400-1600 CE.

Canada

A totem pole in Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia.

A totem pole in Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia. From Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia.

From Totem Park, Victoria, British Columbia.

Caribbean

See also

- Art history

- Aztec clothing

- Cascajal Block

- Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- History of painting

- History of the Americas

- List of indigenous artists of the Americas

- Ledger art

- Maya script

- Mississippian culture

- Native American art

- Native Americans in the United States

- Plains hide painting

- Timeline of Native American art history

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Western art

- Western painting

- Pictogram

References

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble. Scientist at Work: Anna C. Roosevelt; Sharp and To the Point In Amazonia. New York Times. 23 April 1996

- ↑ Bement, 176

- ↑ Davies, p. 78.

- ↑ Pasztory (1977, pp.83–85).

- ↑ Pasztory (1977, pp.87–91).

- ↑ Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya, Sixth edition, New York: Thames & Hudson, pp. 125-129. ISBN 0-500-28066-5

- ↑ On Nazca ceramics retrieved May 12, 2009

- ↑ Bement, Leland C. Bison hunting at Cooper site: where lightning bolts drew thundering herds. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8061-3053-8. Pages 37, 176

- ↑ Turner, Ellen Sue. "The Fremont People of Range Creek Canyon, Utah." Archived 2010-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Southern Texas Archeological Association. 2004 (retrieved 9 May 2010)

- ↑ "Gila Pottery." Archived 2010-05-30 at the Wayback Machine E-Museum of the Minnesota State University, Mankato. (retrieved 9 May 2010)

- ↑ Penney, 129

Sources

- Millon, Clara; Millon, Rene; Pasztory, Esther; Seligman, Thomas K. (1988) Feathered Serpents and Flowering Trees: Reconstructing the Murals of Teotihuacan, Kathleen Berrin, ed., Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

- Dale M. Brown ed. Lost Civilizations: The Magnificent Maya. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life books, 1993.

- Carol Kaufmann. 2003. "Maya Masterwork". National Geographic December 2003: 70-77.

- Constantino Reyes-Valerio, "De Bonampak al Templo Mayor, Historia del Azul Maya en Mesoamerica", Siglo XXI Editores, 1993.

- Davies, Nigel (1982). The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013587-1.

- Pasztory, Esther (1971). "The Murals of Tepantitla, Teotihuacan" (PhD thesis). Columbia University.

- Pasztory, Esther (1977). "The Gods of Teotihuacan: A Synthetic Approach in Teotihuacan Iconography". In Alana Cordy-Collins; Jean Stern (eds.). Pre-Columbian Art History: Selected Readings. Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications. pp. 81–95. ISBN 0-917962-41-9. OCLC 3843930.

- Leibsohn, Dana, and Barbara E. Mundy, “Making Sense of the Pre-Columbian,” Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820 (2015). http://www.fordham.edu/vistas.

External links

- Web page of the Maya Blue Pigment

- Maya Art with Photos

- "Hieroglyphs and History at Copán" article by Mayanist epigrapher David Stuart at the Peabody Museum

- Teotihuacan Research Guide, academic resources and links, maintained by Temple University

- Teotihuacán Photo Gallery

- Mesoamerican Photo Archives: Teotihuacán, by David Hixson

- Teotihuacan Mural Art: Assessing the Accuracy of its Interpretation